Wellbeing & Inclusion News

SCHOOL REFUSAL

Many schools, including ours, are experiencing a significant increase in school refusal. This trend has been steadily increasing since home-schooling during COVID lockdowns and is a challenging issue to work through.

Below is some information about school refusal, including helpful tips if your child is refusing.

What is school refusal?

School refusal is when children get extremely upset or anxious at the idea of going to school and often miss some or all of the school day.

School refusal can mean that children have trouble going to school or trouble leaving home, so they might not go to school at all. Children who refuse to go to school usually spend the day at home with their parents’ knowledge, even though their parents try hard to get them to go.

School refusal is not a formal psychiatric diagnosis. It’s a name for an emotional problem.

Signs of school refusal

If your child refuses to go to school, you might feel that school nights and mornings are a ‘battle of wills’. Your child might:

- cry, throw tantrums, yell or scream

- hide or lock themselves in their room

- refuse to move

- beg or plead not to go

- complain of aches, pains and illness before school, which generally get better if you let your child stay at home

- show high levels of anxiety

- have trouble sleeping

- threaten to hurt themselves.

School refusal can be an issue for children in both primary and secondary school, but it’s more common in children aged 5-6 years and 10-11 years.

Causes of school refusal

There’s rarely a single cause of school refusal. It might be linked to anxiety or worries about leaving home, a phobia, learning difficulties, social problems at school, or depression.

School refusal might start gradually or happen suddenly. It can happen at the same time as or after:

- stressful events at home or school or with peers

- family and peer conflict

- starting or changing schools

- moving home

- bullying or teasing

- problems with a teacher

- poor school results.

By not going to school, a child might be able to:

- avoid scary things – for example, tests, certain teachers, the canteen and so on

- get out of social situations with peers or teachers

- keep an eye on what’s happening at home – for example, if a family member or pet is ill.

Understanding your child’s school refusal

The first step to working on school refusal is trying to understand the issue from your child’s point of view. This means you can go to the school with useful information.

Identifying why your child is having trouble going to school

- Talk with your child about school and why they don’t want to go. Try to find out whether your child is having problems with peers or teachers, or whether they’re trying to avoid something. For example, ‘If you could change one thing about school, what would it be?’

- If your child finds it hard to talk about the problem, ask your child to rate each part of the school day – for example, classroom, specialist classes, teacher, peers, recess and lunch breaks. Younger children might find it easier to tell you how they feel by pointing to symbols like sad faces or smiley faces.

- Think about whether there’s anything happening at home that’s making it hard for your child to leave and go to school. For example, have you had a death in the family or recently moved house? Is your child worried about someone at home, or is your dog unwell?

Finding solutions to school refusal

- Help your child to use a problem-solving approach to the things that make it hard for them to leave home or go to school.

- Tell your child that you’re going to work together with their school to help them go to school.

- Talk with your child about seeing a counsellor or psychologist if they feel they can’t manage their worries or fears about school.

It’s important for your child to go to school while they’re getting help with the issue that has caused the school refusal. When your child goes to school, it builds their confidence and resilience. It keeps your child connected with learning, and it’s important for social development. It’s often easier for children to return to school if they haven’t been away from school for too long.

Working with schools on school refusal

The best way to get your child back to school is by working as a team with your child’s school. It’s a good idea to start by talking with your child’s classroom teacher.

Here are things you could cover:

- Explain what’s going on for your child and why your child is refusing to go to school – for example, bullying, learning difficulties, mental health problems and so on.

- Work together with the school wellbeing team on ways to make your child feel more relaxed and comfortable at school

- Discuss things that may distract them such as doing a job before school for the teacher, playing on the playground

- Encourage them to be independent by carrying their own bag

- For acute, prolonged school refusal, talk with the wellbeing team about a gradual start back at school for your child. For example, your child might be able to start with a shorter school day or with their favourite subjects and build up from there.

Working on school refusal at home: practical strategies

Here are practical things you can do at home to encourage your child to go to school.

When you’re talking to your child:

- Show your child that you understand. For example, you could say, ‘I can see you’re worried about going to school. I know it’s hard, but it’s good for you to go. Your teacher and I will help you’.

- Use clear, calm statements that let your child know you expect them to go to school. Say ‘when’ rather than ‘if’. For example, you can say, ‘When you’re at school tomorrow ...’ instead of ‘If you make it to school tomorrow ...’.

- Show that you believe your child can go to school by saying positive and encouraging things. For example, ‘You’re showing how brave you are by going to school’. This will build your child’s self-confidence.

- Use direct statements that don’t give your child the chance to say ‘No!’ For example, ‘It’s time to get out of bed’ or ‘Jo, please get up and into the shower’.

- Talk about school in a positive way

When you’re at home with your child:

- Stay calm. If your child sees that you’re worried, stressed or frustrated, it can make your child’s anxiety worse.

- Plan for a calm start to the day by having morning and evening routines. For example, get uniforms, lunches and school bags ready the night before, get your child to have a shower or bath in the evening, and get your child to bed at a regular time.

- Praise your child when they show brave behaviour, like getting ready for school. For example, you could say, ‘I know this is hard for you, but I think it’s great that you’re giving it a go. Well done’.

- Make your home ‘boring’ during school hours so that you don’t accidentally reward your child for not going to school. This means little or no TV or video games and so on. You could think about not letting your child use their iPad during school hours.

Getting to school

- Get someone else to drop your child at school, if you can. Children often cope better with separation at home rather than at the school gate.

- Praise your child when they actually go to school. You could also consider rewarding them. For example, if your child goes regularly, they could earn bonus technology time, a special outing with a parent to their favourite park, or their favourite meal for dinner.

Your child needs your love and support to get back to school. So focus on any efforts your child makes to go back, be patient with your child’s progress, and try to keep any frustration to yourself. This will help your child build the confidence they need to get back to school regularly.

Getting professional help for school refusal

Families can get professional help to learn about managing school refusal and to sort out the problems behind it.

If your child is saying they feel sick, make an appointment with your GP to check it out.

If there are no physical reasons for your child feeling sick, your GP might refer you to a paediatrician, psychiatrist or psychologist.

A psychiatrist or psychologist will usually do an assessment to see whether the school refusal is linked to issues like anxiety or depression. Therapies and supports for school refusal will probably work better if your child is also getting help for anxiety or depression.

It’s a good idea to ask your child’s health professional about any strategies you can use at home to support your child’s return to school.

Your GP will probably talk with you about a Mental Health Treatment Plan for your child. If you have a plan, you can get Medicare rebates for up to 10 sessions with a mental health professional. You can also get Medicare rebates for visits to a paediatrician.

Adapted from Raising Children’s Network

Community Collective Victoria - Psychologists and Counsellors

Community Collective Self Referral Form:

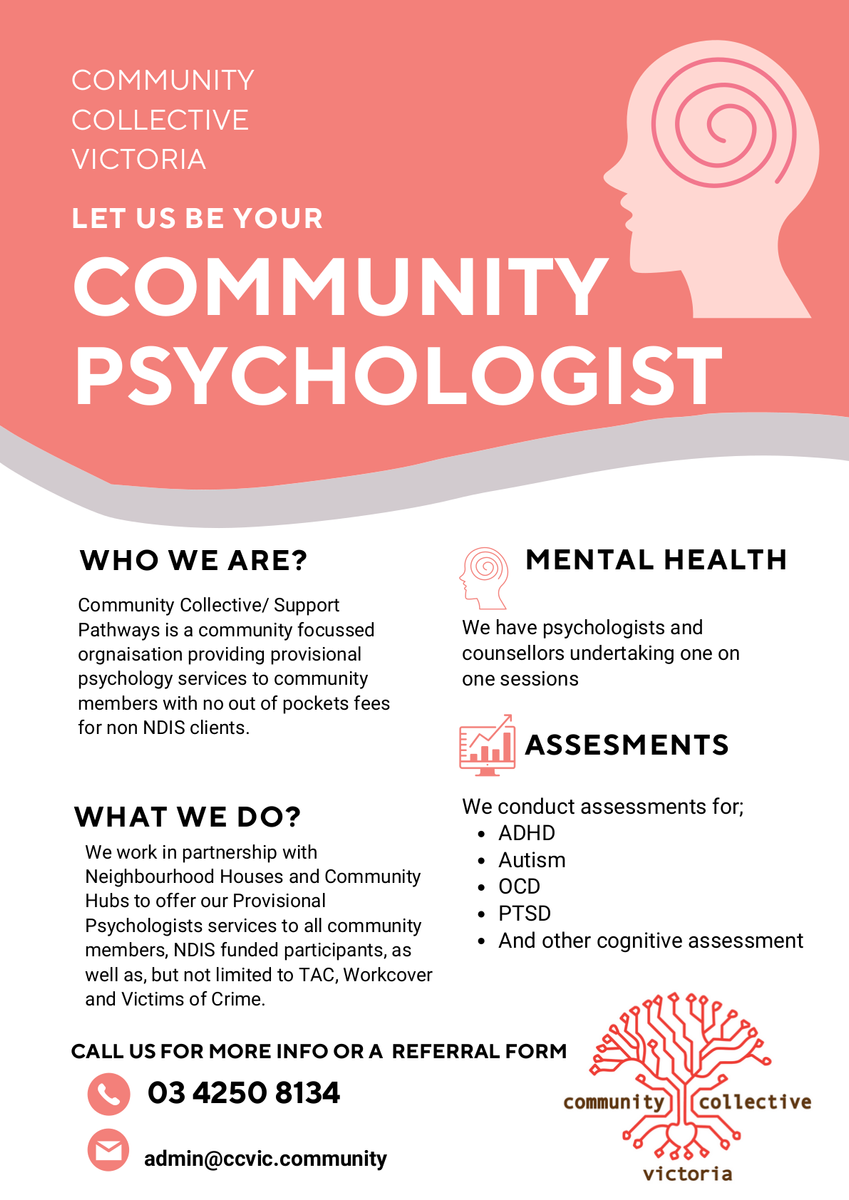

VU Psychology Clinic

The Victoria University psychology clinic, located at Metrowest in the heart of Footscray currently has NO WAITLIST for therapies. The clinic offers individual therapy (Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and Psychodynamic Therapy) to adults and children and also runs various group programs, all for the one-off cost of $20.

The clinic also offers cognitive assessments and reports at a flat rate of $250, or $50 for a health care cardholder.

The psychology students who provide the psychological services in the clinic are AHPRA registered provisional psychologists and supervised by experienced psychologists and endorsed AHPRA supervisors.

Contact details and more information regarding eligibility and access can be found on the VU website http://vu.edu.au/psychology-clinic as well as on the below flyer.