Teaching & Learning Page:

Web Pages:

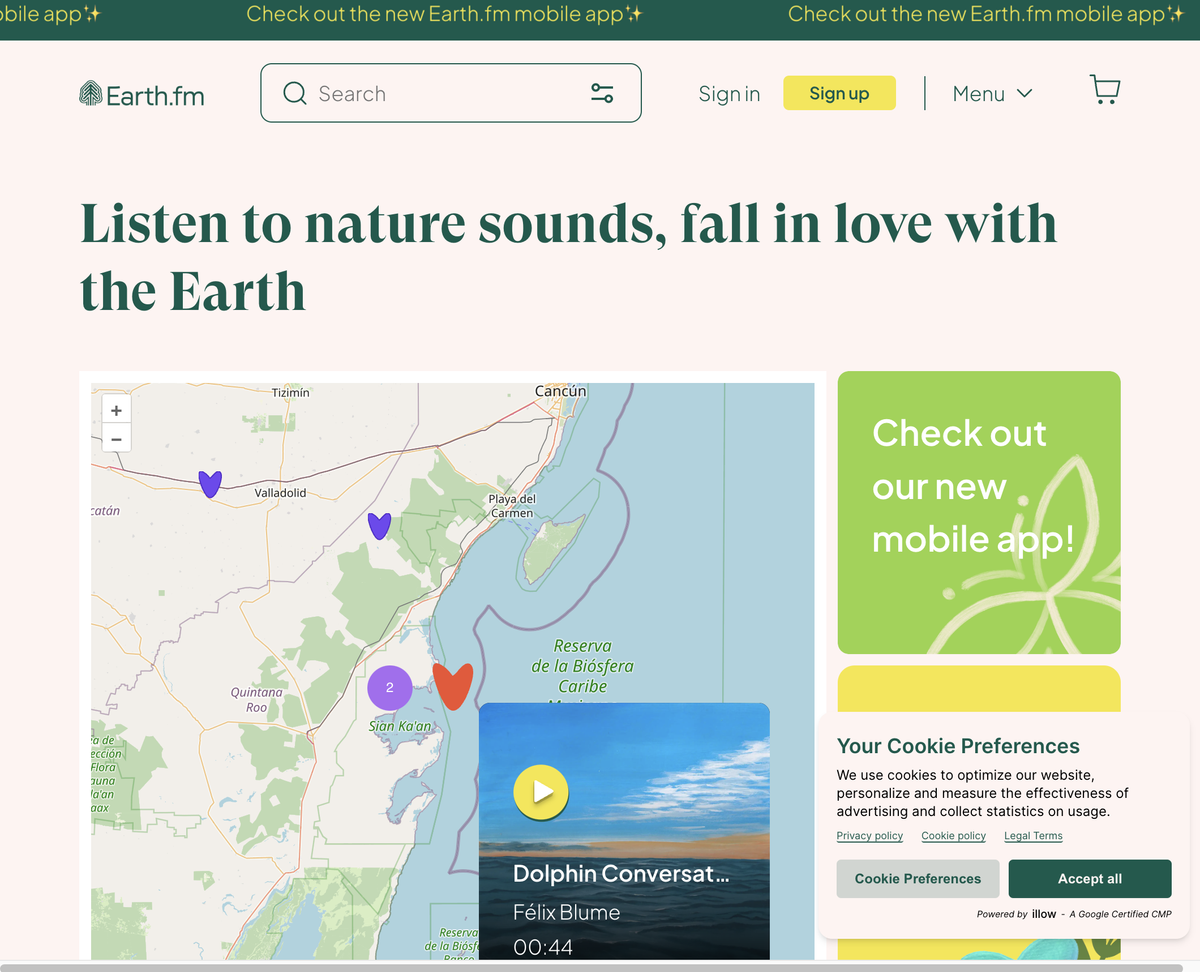

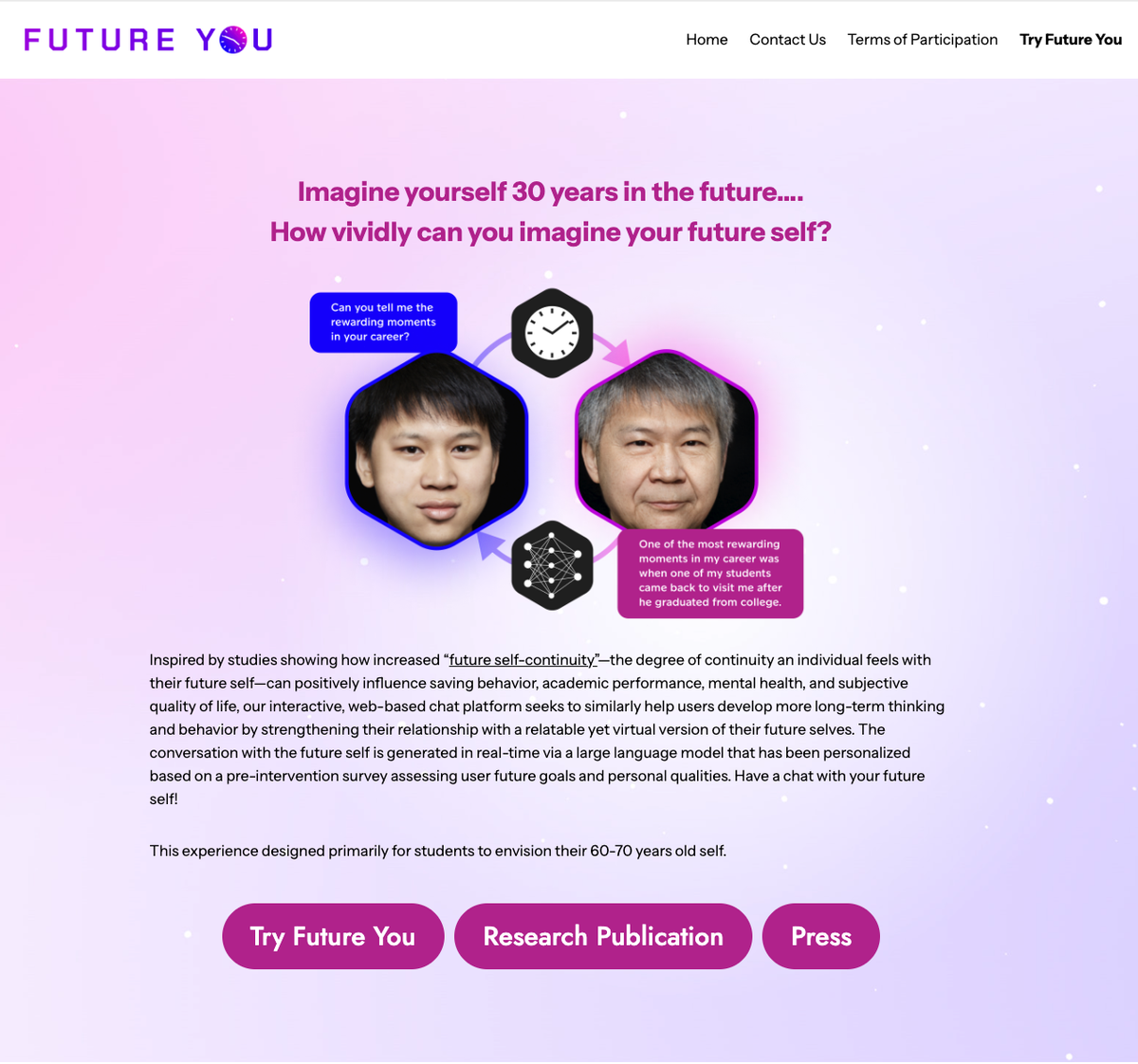

https://futureyou.media.mit.edu/

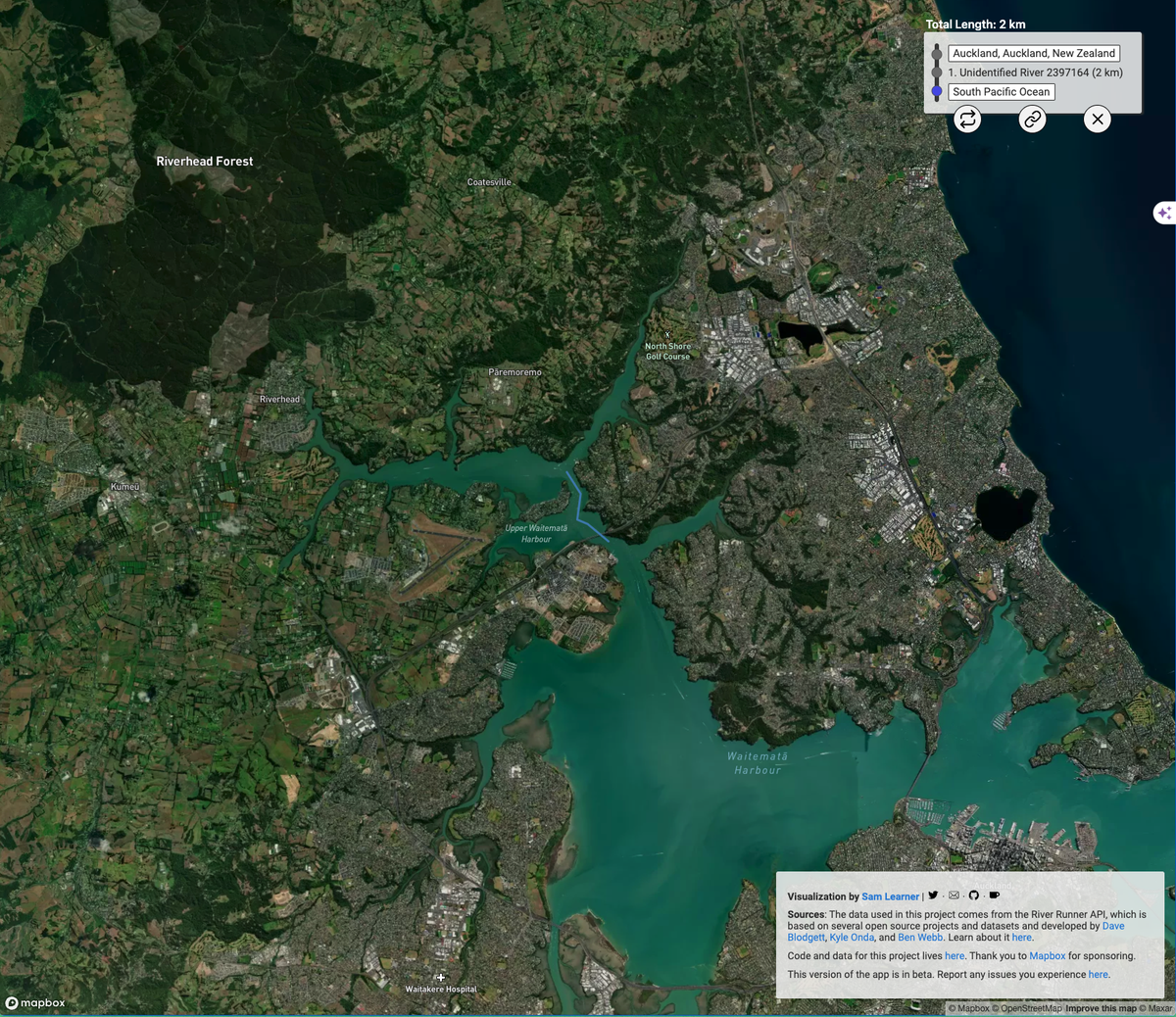

https://river-runner-global.samlearner.com/

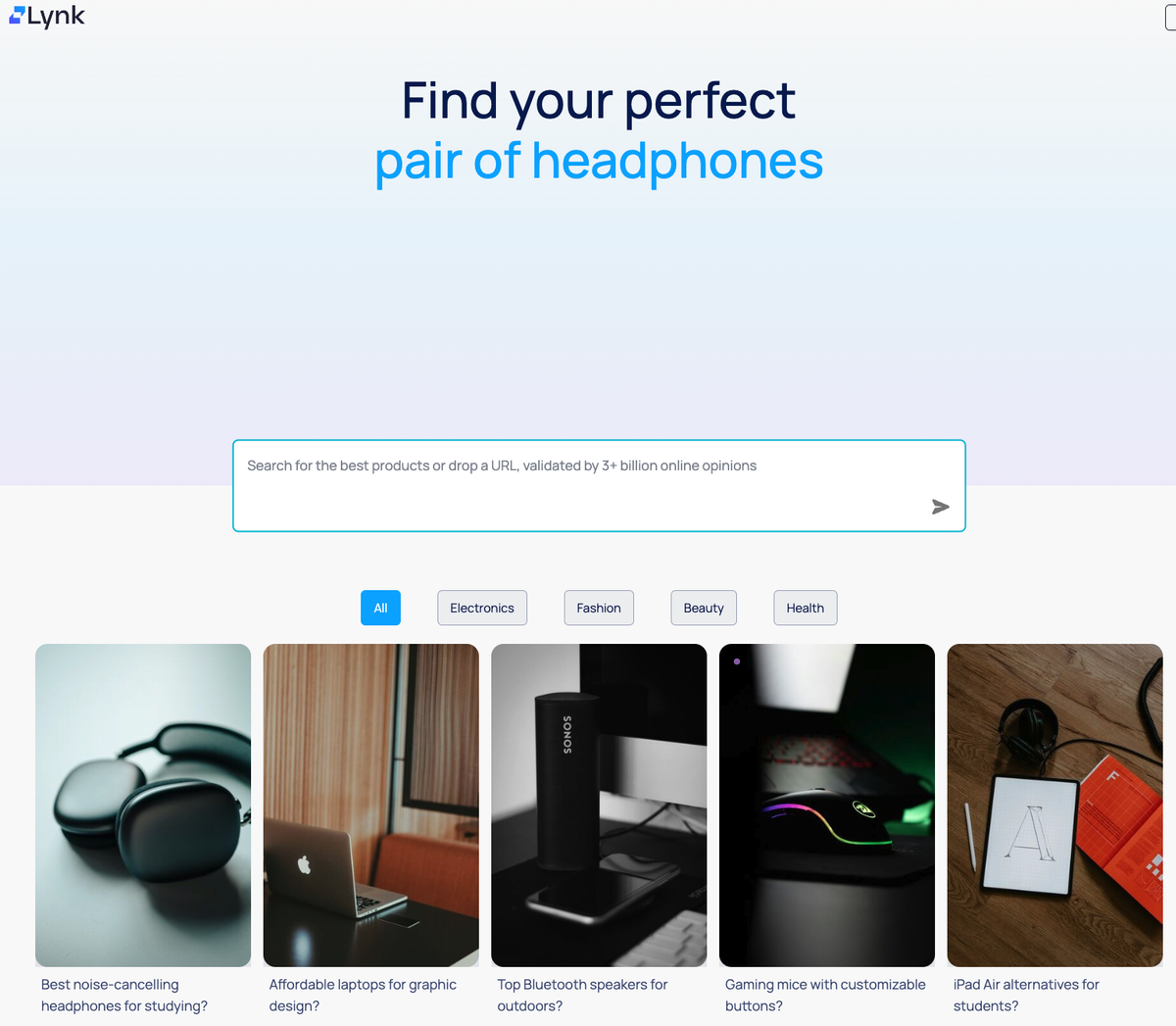

Not just headphones - collated user reviews of all kinds of products.

Finding Calm Amidst Crisis

Former U.S. President Barack Obama on cultivating composure and focus.

"I’ve often been asked about this personality trait—my ability to maintain composure in the middle of crisis. Sometimes, I’ll say that it’s just a matter of temperament or a consequence of being raised in Hawaii since it’s hard to get stressed when it’s eighty degrees and sunny and you’re five minutes from the beach. If I’m talking to a group of young people, I’ll describe how over time I’ve trained myself to take the long view, about how important it is to stay focused on your goals rather than getting hung up on the daily ups and downs.”

Beliefs are theories. Actions are experiments. Emotions are feedback. Life is a

science and its objective is growth.

Techie Tips:

iOS 18 Tricks You’ll Use:

Copy Specific Edits Between Photos

If you’ve ever edited a picture just the way you want and wished you could apply the same

tweaks to many others, now you can. In iOS 18, you can copy just the filter or just the

exposure changes from one photo and paste them onto another. It’s perfect for creating

consistency across your photo albums.

Real-Time Math Calculations in iMessage

Need to send someone a quick calculation? With iOS 18, you don’t need to leave the

Messages app. Just type a math problem right in the message, hit “=”, and iOS will calculate it for you. It’s perfect for settling those quick “Who owes what” debates.

Sketchplanations:

Five ways to wellbeing -

Connect... Be active... Take notice... Keep learning... Give...

The five ways to well-being are five simple, evidence-based ways to improve mental capital and well-being throughout life.

Connect

With the people around you. With family, friends, colleagues and neighbours. At home, work, school or in your local community. Think of these as the cornerstones of your life and invest time in developing them. Building these connections will support and enrich you every day.

Be active

Go for a walk or run. Step outside. Cycle. Play a game. Garden. Dance. Exercising makes you feel good. Most importantly, discover a physical activity you enjoy and that suits your level of mobility and fitness.

Take notice

Be curious. Catch sight of the beautiful. Remark on the unusual. Notice the changing seasons. Savour the moment, whether you are walking to work, eating lunch or talking to friends. Be aware of the world around you and what you are feeling. Reflecting on your experiences will help you appreciate what matters to you.

Keep learning

Try something new. Rediscover an old interest. Sign up for that course. Take on a different responsibility at work. Fix a bike. Learn to play an instrument or how to cook your favourite food. Set a challenge you will enjoy achieving. Learning new things will make you more confident as well as being fun.

Give

Do something nice for a friend, or a stranger. Thank someone. Smile. Volunteer your time. Join a community group. Look out, as well as in. Seeing yourself, and your happiness, linked to the wider community can be incredibly rewarding and creates connections with the people around you.

What Works

Wellbeing has a neat post on how the UK compares to other European countries on the 5 ways to well-being and how they are affected by age, gender, and other factors: 5 ways to well-being in the UK.

Here is some simple wisdom from Kurt Vonnegut: Notice when you’re happy.

“My uncle Alex Vonnegut, a Harvard-educated life insurance salesman who lived at 5033 North Pennsylvania Street, taught me something very important.

He said that when things were really going well, we should be sure to notice it. He was talking about simple occasions, not great victories: maybe drinking lemonade on a hot afternoon in the shade or smelling the aroma of a nearby bakery, fishing and not caring if we caught anything or not, or hearing somebody all alone playing a piano really well in the house next door.

During such epiphanies, Uncle Alex urged me to say this out loud: “If this isn’t nice, I don’t know what is.”

Kurt goes on to say:

"So I do the same now, and so do my kids and grandkids. And I urge you to please notice when you are happy and exclaim or murmur or think at some point, ‘If this isn’t nice, I don’t know what is.”

Perhaps, needless to say, so do I.

Article:

The “Rule of Saint Benedict”: A medieval blueprint for modern time management:

Oliver Burkeman — author of “Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals” —

tells Big Think about modern life lessons from a 6th-century monk.

Key Takeaways

In the 6th century, St. Benedict of Nursia established the “Rule of Saint Benedict,” which

emphasises moderation, work, and prayer.

Under the rule, monks worked for only a defined time and then moved on to something else.

Big Think spoke to author Oliver Burkeman about how the rule is a helpful reminder

of how to approach our finite lives.

Benedict was the son of a wealthy, noble family in 6th-century Italy. He was a pious and

diligent boy, and when he was old enough, he moved to Rome to study classics but

quickly grew bored with the prattling about that defined student life. Worried over his

learning and his soul, Benedict did what any one-day saint would do: He went to live as a

hermit and contemplate God.

Sadly for Ben, word got around, and before long, a group of wayward monks asked for his

help. They wanted him to be the abbot of their monastery. Torn from his prayers and

somewhat cynical of common men, Ben agreed but warned they wouldn’t like his style of

abbacy.

Benedict was right. His austere and strict regime proved as popular as a splintery prayer

stool. The monks were so unhappy that they tried to poison their new abbot. Twice.

Whether by divine intervention or mortal cunning, Benedict survived the attempts on his

life. He got the message, though. He left the monks behind and travelled southeast to

Monte Cassino, where he established a new order governed by a system that would go

on to redefine European life.

This is the story of Saint Benedict of Nursia, and when Big Think spoke with Oliver

Burkeman, the bestselling author of Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for

Mortals, he told us we still have a lot to learn from old Ben.

The unfinished job

From that first attempt at monastic rule-making — and two attempts on his life — Saint

Benedict devised what is now known as “the Rule of Saint Benedict.” This new approach

was not some puritanical sermon from the pulpit demanding miserable self-denial with the scourge close at hand. Instead, as Burkeman put it, it was “a sort of model of moderation and rhythm that finds time for work, time for prayer, and time for rest.” It was something you could live with, something you could flourish with.

Burkeman tells us that the Rule of Saint Benedict says, “Look, it’s best not to drink lots of

alcohol, so if you’re going to drink alcohol, just don’t drink so much, okay? Over and over

again, it has this amazing spirit of gentle moderation.”

One of the great ideas of Benedictine life was that you stopped any task you were doing

when the time was up. The monks knew there was always one more thing to do — a weed to pull, a meal to prepare, or a prayer to offer up. But they allocated a set amount of time to

a task, and that was it.

“One of the things I love about that idea is with work,” Burkeman says. “There is a

monastic work period within the unfolding Benedictine day. When it’s done, the bell rings,

you put down the work, and you go on to the next thing. You don’t only put down the work

when it’s finished; of course, the work is never finished. We could really do with being

reminded, I think, in the world today that the work is never finished. You need instead to

develop that willingness to do your part for the day and declare that you have done

enough.”

The monk inside

If you read Burkeman’s book, one theme that pops up again and again is embracing what

he calls our “cosmic insignificance.” This isn’t some self-doubting inferiority complex that

makes you shuffle from shadowy corner to shadowy corner. Instead, it is accepting that

“how you use your time is not going to matter too much in a couple hundred years.” It’s

the realization that you will only occupy this space and time for a select few years, or, if

you’re more Benedictian about it, you’ve been given a select few years. Realising you have limited resources and are only one person “takes the pressure off a bit.” You will

never achieve everything there is to achieve, and you will have to decide what to exclude

from your finite life’s passing.

It’s no accident then that Burkeman calls upon the Rule of Saint Benedict because, say

what you want about monks, they have an overwhelming sense of their finitude. They

recognise that their task is a human one and that it’s the height of hubris to assume that

any mortal can achieve immortality. It’s a sin — a sin of human pride — to think we can

do everything. We only have 4,000 weeks, as Burkeman puts it, or the “saeculum,” as

Augustine did. We have a human life. And the most existentially important part of that life

is choosing how to devote it.