The Not Green BLUE Page:

by Ethan Siegel, Ph.D., author of Beyond The Galaxy,

The Not Green BLUE Page:

by Ethan Siegel, Ph.D., author of Beyond The Galaxy,

The sky is blue. The oceans are blue. While science can explain them both, the reasons for each are entirely different.

Contrary to what you might have read, there’s no one single factor responsible for Earth’s blue skies.

The skies aren’t blue because sunlight has a blue tint; our Sun emits light of many different wavelengths, and that light sums up to be a net white colour.

Oxygen itself isn’t a blue-coloured gas, but rather is transparent to light.

However, there are a myriad of molecules and larger particles in our atmosphere that do play a role, scattering light of different wavelengths by different amounts. The ocean plays no role in the colour of the skies, but the sensitivity of our eyes absolutely does: we do not see reality as it is, but rather as our senses perceive it and our brain interprets it.

These three factors — the Sun’s light, the scattering effects of Earth’s atmosphere, and the response of the human eye — are what combine to give the sky its blue appearance.

When we pass sunlight through a prism, we can see how it splits up into its individual components. The highest-energy light is also the shortest-wavelength (and high-frequency) light, while the lower-energy light has longer wavelengths (and low frequencies) than its high-energy counterparts.

The thin coatings on your sunglasses reflect ultraviolet, violet, and blue light, but allow the longer-wavelength greens, yellows, oranges, and reds to pass through. And the tiny, invisible particles that make up our atmosphere — molecules like nitrogen, oxygen, water, carbon dioxide, as well as argon atoms — scatter light of all wavelengths, but preferentially are more efficient at scattering bluer, shorter-wavelength light.

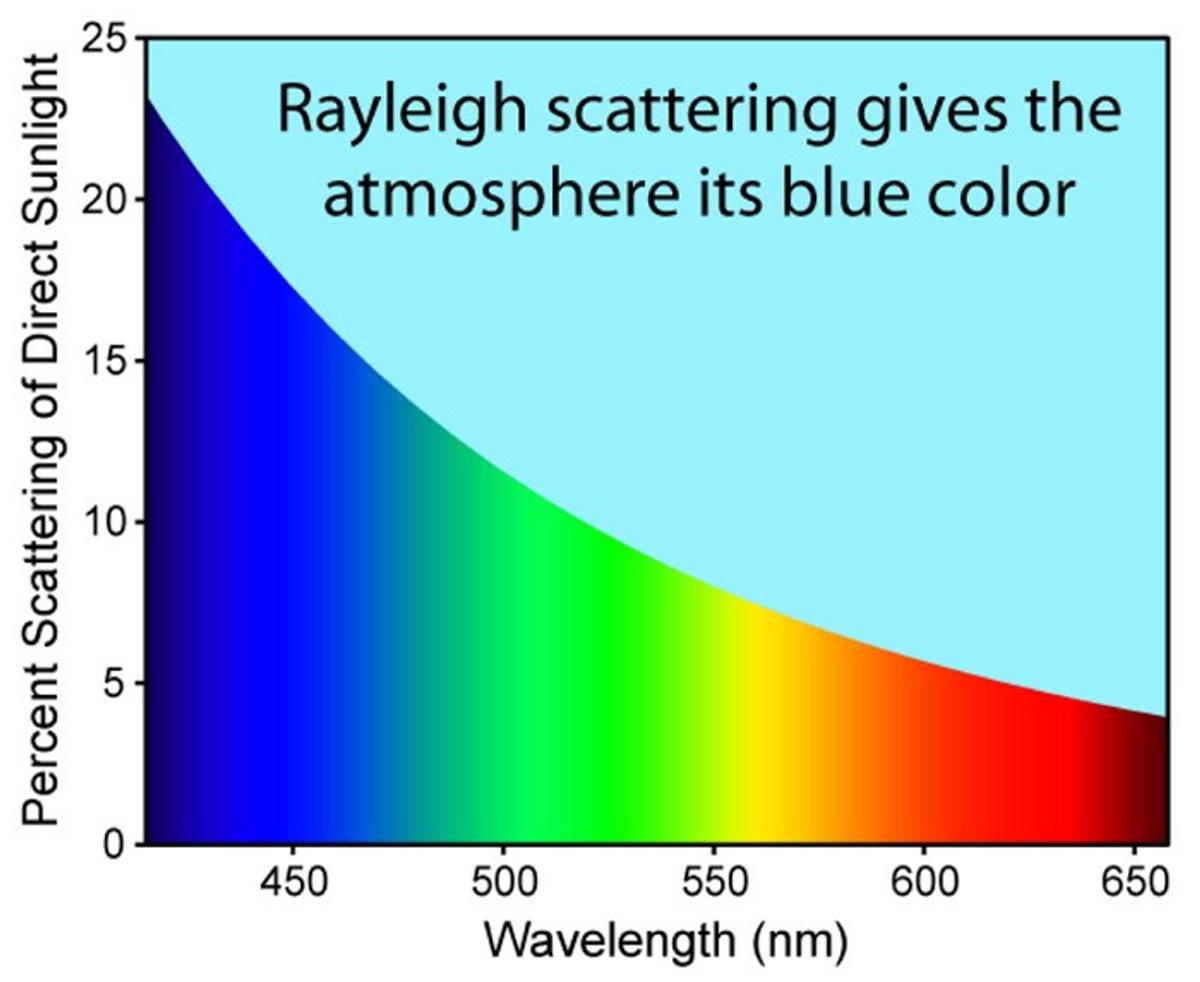

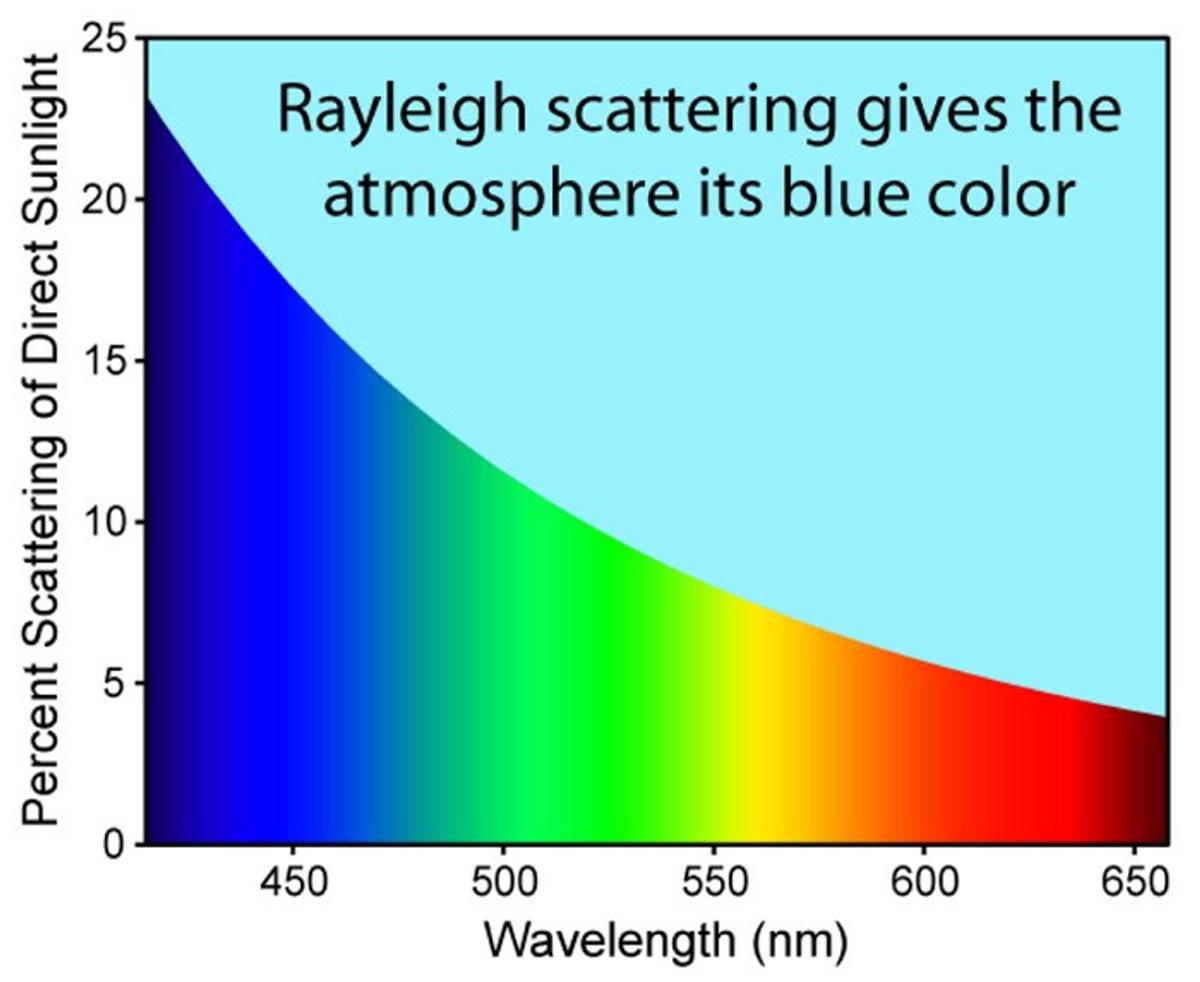

There’s a physical reason behind this: all the molecules making up our atmosphere are smaller in size than the various wavelengths of light that the human eye can see. The wavelengths that are closer to the sizes of the molecules present will scatter more efficiently; quantitatively, the law it obeys is known as Rayleigh scattering.

The violet light at the short-wavelength limit of what we can see scatters over nine times more frequently than the red, long-wavelength light at the other end of our vision. This is why, during sunrises, sunsets, and lunar eclipses, red light can still pass efficiently through the atmosphere, but the bluer wavelengths of light are practically non-existent, having been preferentially scattered away.

Since the bluer wavelengths of light are easier to scatter, any incoming direct sunlight will become redder and redder the more atmosphere it passes through. The remainder of the sky, however, will be illuminated by indirect sunlight: light that strikes the atmosphere and then gets redirected towards your eyes. The overwhelming majority of that light will be blue in wavelength, which is why the sky is blue during the day.

It will only take on a redder hue if there’s enough atmosphere to scatter that blue light away before it reaches your eyes. If the Sun is below the horizon, all the light has to pass through large amounts of atmosphere. The bluer light gets scattered away, in all directions, while the redder light is far less likely to get scattered, meaning it takes a more direct path to your eyes. If you’re ever up in an aeroplane after sunset or before sunrise, you can get a spectacular view of this effect.

This might explain why sunsets, sunrises, and lunar eclipses are red but might leave you wondering why the sky appears blue instead of violet. Indeed, there actually is a greater amount of violet light coming from the atmosphere than blue light, but there’s also a mix of the other colours as well. Because your eyes have three types of cones (for detecting colour) in them, along with the monochromatic rods, it’s the signals from all four that need to get interpreted by your brain when it comes to assigning a colour.

Each type of cone, plus the rods, is sensitive to light of different wavelengths, but all of them get stimulated to some degree by the sky. Our eyes respond more strongly to blue, cyan, and green wavelengths of light than they do to violet. Even though there’s more violet light, it isn’t enough to overcome the strong blue signal our brains deliver, and that’s why the sky appears blue to our eyes.

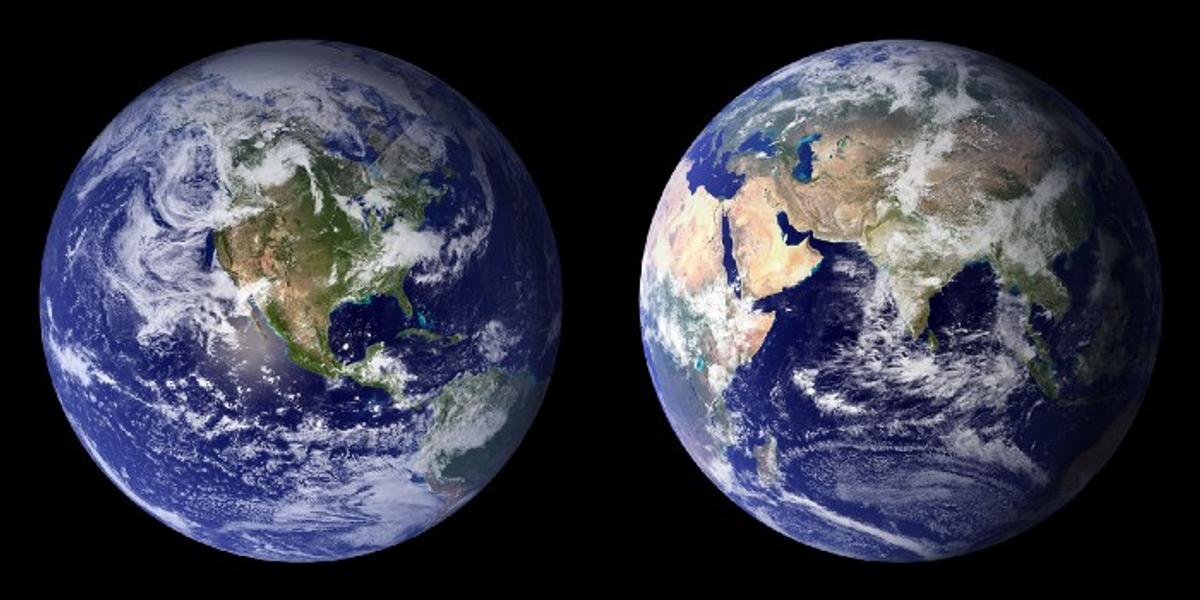

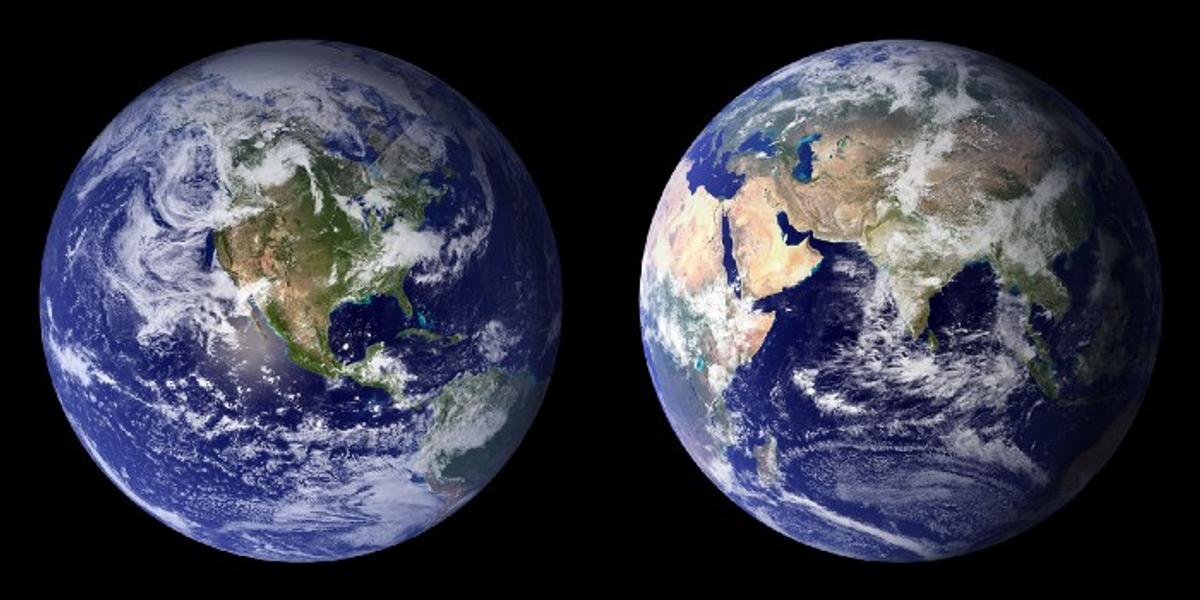

The oceans, on the other hand, are an entirely different story. If you take a look at the planet as a whole, with a view such as the one you get from space, you’ll notice that the bodies of water we have aren’t a uniform blue, but rather vary in their shade based on the water’s depth. Deeper waters are a darker blue; shallower waters are a lighter blue.

You’ll notice if you look closely at a photo like the one below, that the watery regions bordering the continents (along the continental shelves) are a lighter, more cyan shade of blue than the deep, dark depths of the ocean.

If you want a more direct set of evidence that the oceans themselves appear blue, you could try diving down beneath the water’s surface and recording what you see. When we do this, taking a photograph underwater in natural light — i.e., without any artificial light sources — we can immediately see that everything takes on a bluish hue.

The farther down we go, as we reach depths of 30 meters, 100 meters, 200 meters and more, the bluer everything appears. This makes a lot of sense when you remember that water, just like the atmosphere, is also made out of molecules of finite size: smaller than the wavelengths of any light that we can see. But here, in the depths of the ocean, the physics of scattering is a little different.

Instead of scattering, which is the primary role of the atmosphere when light passes through it, a liquid like water primarily absorbs (or doesn’t absorb) light. Water, like all molecules, has a preference for the wavelengths it can absorb. Rather than having a straightforward wavelength dependence, water can most easily absorb infrared light, ultraviolet light, and red visible light.

This means if you head down to even a modest depth, you won’t experience much warming from the Sun, you’ll be protected from UV radiation, and things will start to turn blue, as the red light is taken away. Head down a little deeper, and the oranges go away, too.

Past that, the yellows, greens and violets start to get taken away. As we head down to depths of multiple kilometres, finally the blue light disappears as well, although it’s the last to do so.

This is why the deepest ocean depths appear a deep, dark blue: because all the other wavelengths get absorbed. The deepest blues, unique among all the wavelengths of light in water, have the highest probability of getting reflected and re-emitted back out.

The sky and ocean aren’t blue because of reflections at all; they’re both blue, but each of their own volition. If you took our oceans away entirely, a human on the surface would still see blue skies, and if you managed to take our skies away (but still somehow gave us liquid water on the surface), our planet would still appear blue from far away in space.

For the skies, the blue sunlight scatters more easily and comes to us indirectly from where sunlight strikes the atmosphere as a result. For the oceans, longer-wavelength visible light gets absorbed more easily, so the deeper they go, the darker blue the remaining light appears. Blue atmospheres may be common for planets, as Uranus and Neptune both possess them, too, but we’re the only ones we know of with a blue surface. Perhaps when we find another world with liquid water on its surface, we’ll discover that we aren’t so unique after all, and in more ways than we even presently realize!