Parent Page

Tips for parenting

Parent Page

Tips for parenting

We group and categorise children by age so frequently that it seems remarkable that there was a time where this would be considered unusual. Until the latter 1800s age did not really signify a whole lot at all. This was even the case at school where children of all ages were grouped together and taught based on ability rather than chronology. (It’s likely that many of the children in those early schools didn’t even know how old they were!)

By the time our children have “graduated” from their preschool years they’re ready for big school. In Australia, it’s Primary School. Our kids are so small that it might seem like they’re still toddling off to kindergarten, reception, or prep (depending on which Australian state you’re in), and unfortunately in Western Australia and Tasmania they are only just out of being toddlers when school commences. It’s hard to make an argument that they’re ready for big school at age four, but that’s the time it starts for too many.

Nevertheless, most children are raring to go when big school arrives. If we’ve allowed time for healthy development they’re up for the challenge of new learning (cognitive development needs to have advanced enough), new friends (social development), and expanding their awareness of the world around them. Fortunately, the majority do just fine (with a few challenges here and there). This is the period where they read, understand quantities, develop relationships that can last a lifetime, and start to find out who they really are.

Kids grow, on average, about 6cms each year, and they gain around 2-3 kgs per year throughout primary school (depending on diet and physical activity). As our children mature through the primary years of middle childhood they become stronger and more physically capable. They run faster, throw further, jump higher and perform at a vastly higher capacity than they did even a year or two ago in preschool. Gender differences begin to become more apparent too as girls gain strength at a slower rate than boys (with around 10% less aerobic capacity than their male counterparts). They tend to have slightly poorer hand-eye coordination and less power in running, throwing, and kicking but they stay pretty close physically until puberty kicks in.

Our child’s brain, by about the age of 6 or 7, is around 90% of its adult size and weight. Growth slows through this period. We’re nearly there! But ongoing developments and processes like more white matter (myelinisation) of nerve fibres, more connections between neurons, and more hemispheric specialisation continue.

The frontal cortex develops in important ways and we see attention spans and concentration increase. This continues throughout middle childhood and we find our kids capable of being still, thinking things through, and having rational interactions. Bliss! Planning and reflection become more accessible. The corpus callosum (the fibres connecting both sides of the brain) grows more connections, allowing greater coordination of thinking, motor control, and transmission of brain signals across the brain.

During this stage, our children move from Piaget’s “preoperational thinking” to “concrete operational thinking”. I won’t bore you with all of the jargon around this development, but a couple of important milestones occur - and you can watch these things happen before your eyes. As an example, a hallmark of this shift occurs with something called quantity conservation, which is having the ability to identify how much of something exists.

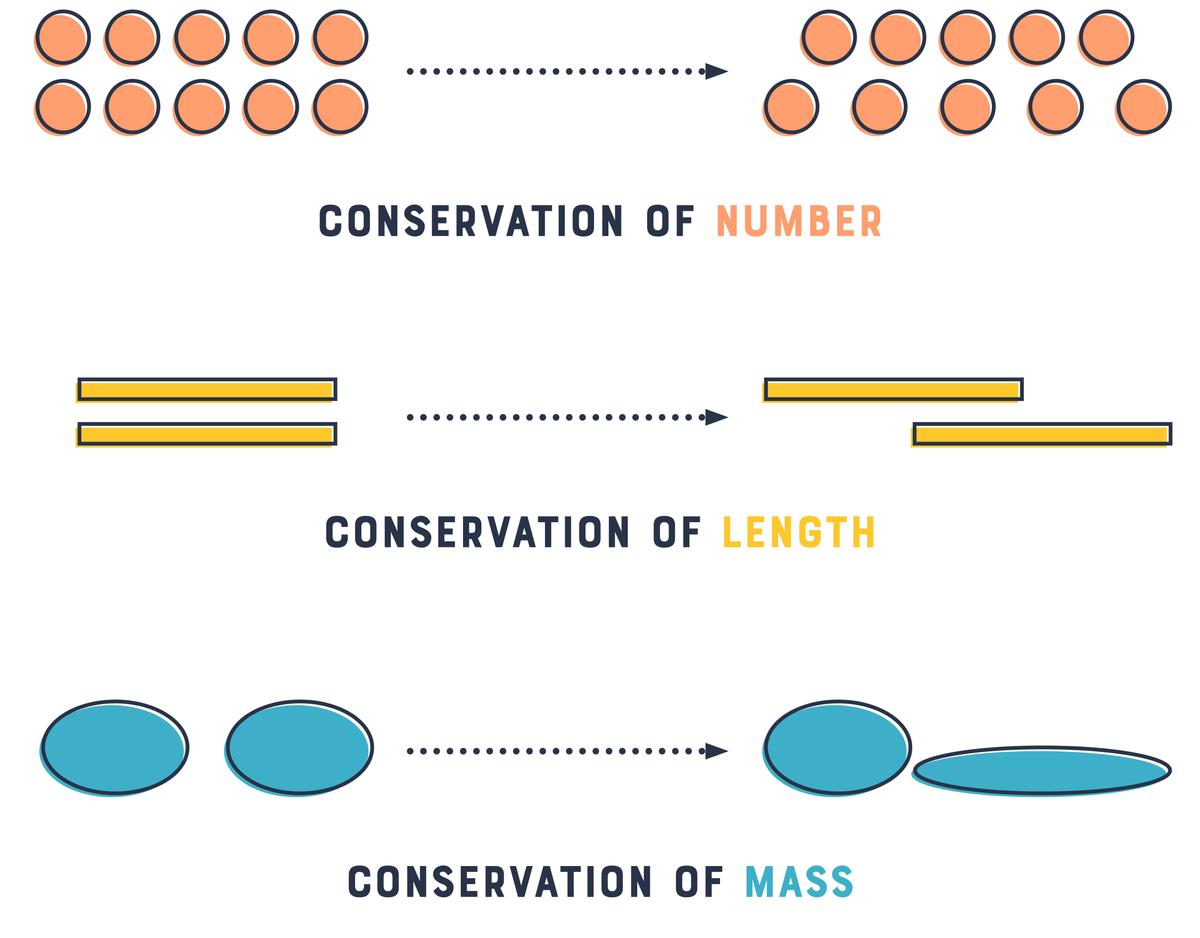

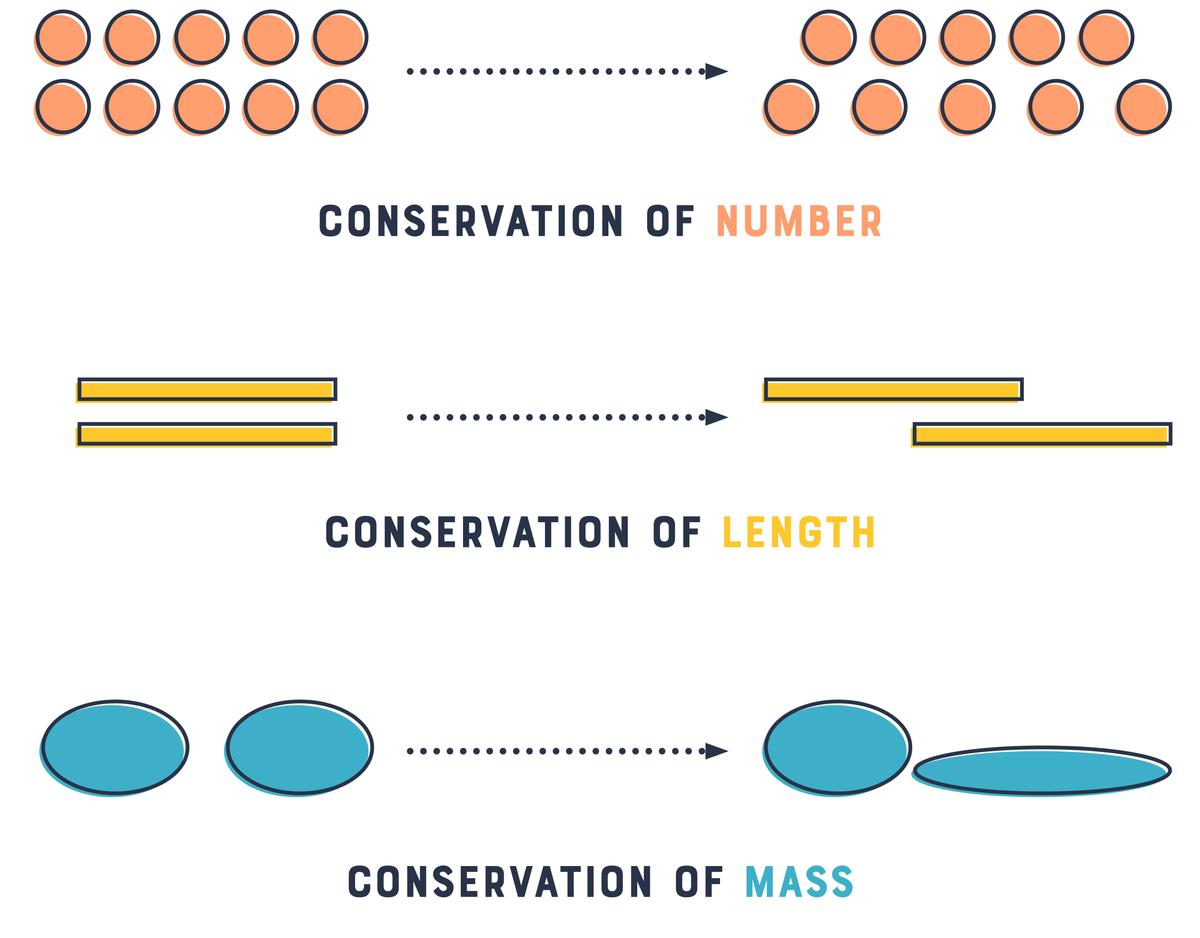

Here are three examples:

If you ask a preschool child, or even a child up to about age six, which row has the most dots, they’ll go for the one that takes up more space even though the number is the same. This is called conservation of number. The child fails to understand that the amount remains the same because the length is greater. In a child’s mind, this means that there is more. As they grow through this stage their cognitive ability develops and they understand conservation. It’s an exciting leap forward! In the second example, asking which is longer will be met with an incorrect response by younger children, and asking which has greater mass (or surface area) will be the same. (There are other forms of conservation, such as weight, area, substance, distance, fluid, and so on.)

We don’t pay pocket money to young kids because they don’t “get” money. The symbolism of it is too confusing for them. Children need to develop the cognitive capacity to understand quantities before money makes sense. This is why they are typically in around Grade 3 (aged 8-ish) before they understand that a $1 coin is better than ten 5c coins. This is the period where maths makes sense, and reading and literacy become primary in our children’s understanding of the world. It’s all to do with Piaget’s concrete operational stage. Symbolic representation through reading and writing (letters make sounds, and sounds make words, and words have meaning) and maths (coins represent purchasing power and have different values) develops. And academic motivation kicks in. For some children this is higher than for others. But a learning and mastery orientation in some domain (sport, academic, music, drama, etc) becomes central to a child’s cognitive growth - and their identity development.

Other important cognitive developments include the ability to follow instructions, hold multiple ideas in their head at once, think through options, ignore something tempting in front of them so they can attend to something more important, think creatively, reflect on ideas, regulate emotions (more on that below), and even form arguments with logic and reasoning.

During primary school years children begin to navigate relationships slightly differently. Girls become more relationally oriented. Boys a little less so. This might be related to changes in language patterns as girls have a wider vocabulary, speak more, and are more oriented towards higher levels of communication, whereas boys tend to speak less and use their bodies more. But by the middle primary school years, one thing is clear: children want friends, they seek cooperation, relationship hierarchies develop, and peers become increasingly important to identity. Tying in with personality development, children who are popular are outgoing, sociable, friendly, love to cooperate, lead, and show good theory of mind development. They tend not to be aggressive but might use aggression from time to time to maintain status.

Oh, and socially, children tend towards playing with same-gender friends and same-age friends. This keeps relationships even, and creates an understanding of how “boys” or “girls” are (which can be reinforcing in both negative and positive ways).

Because theory of mind is developing in the early school years, we see a marked enhancement of our children’s capacity to:

This is no small feat! But they don’t always do it well. Anger still wells up in younger primary school children. And they sometimes become increasingly fearful as their awareness of the big wide world increases.

From around age 6-8 years, children start to understand how they can be happy/sad at the same time. They’re happy their friend won an award but sad they didn’t win one themselves. They also develop an understanding that just because dad is smiling at them in public, it doesn’t mean he is happy with them. Dad’s eyes betray his real feelings and they now have the emotional understanding (theory of mind) to recognise they’re in trouble but dad’s just trying to look like a nice dad. And they now recognise that what makes one person feel good can make another person feel scared or upset (like a rollercoaster at a theme park, or waves at the beach - or even a puppy dog).

From age 9-12 children learn how to hide, mask, or feign emotional states based on the expectations of those around them. And they begin to understand what they need emotionally and seek it out. They might know they need stimulation so they ask to hang out with a friend. Or they might feel overwhelmed and seek peace and calm in the bedroom. And they learn to lie much more cleverly than they have done in the past.

Children begin to experiment with an understanding of boundaries and values, and incorporate these into their perception of who they are. Friends, the media, parents and siblings each influence a child’s development of morality and identity.

During the concrete operational stage rules are very important. Expectations around keeping the rules, not cheating, and the black-and-white of morality are powerfully reinforced.

Finally, to aid in their moral development, talk through hypothetical situations with them. Explore value systems, ideas and ideals, and people from history who have made different contributions to the world. Instill in them a desire to help those less fortunate.

https://www.happyfamilies.com.au/articles/developmental-milestones-part-4