HUMANITIES

DIGGING UP THE PAST

Anyone who has enjoyed the Indiana Jones films would be under the impression that the life of the archaeologist is one of derring-do. There is also a lesson there in the dangers of messing with the spirits of Ancient Egypt. The reality, of course, is rather more prosaic.

There is little romance in shifting many tons of sand and the detritus of countless generations only to reveal a wall. But this is where the imagination takes over as archaeologists and researchers strive to recreate a lost time with the artefacts that remain. The reconstruction of the past is both material and imaginative.

McKinnon is incredibly lucky to have its own resident archaeologist in Dr Long – Indiana Long, if you will. As a student at Monash University, Dr Long was given the opportunity to join an archaeological dig at the Dakleh Oasis in the Western Desert of Egypt. Certain geometric configurations in the sand suggested there was something worth investigating beneath. And so it proved to be.

As ruined walls and living spaces were revealed by the excavations, a whole other life opened itself up for inspection. This is where the real work of archaeology begins, of course, and it is hard yakka. For the archaeologist needs to make sense of what is uncovered. Hypotheses are tested, discarded or modified until a coherent picture of the past is presented for our view. It might not have the same adrenalin rush as an Indiana Jones adventure but it is immensely interesting nonetheless.

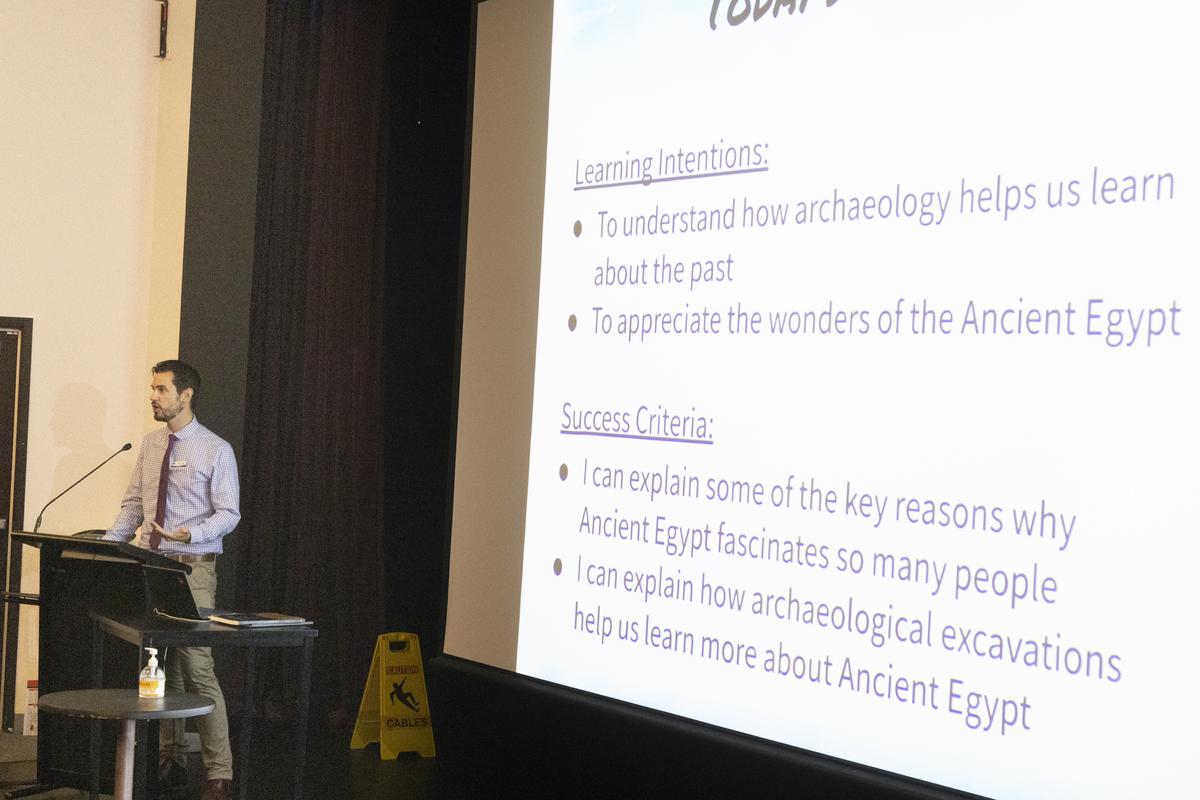

In a lecture to the Year 7 students, Dr Long was able to convey this and more as he described how his intellectual interest was piqued by the mystique of Ancient Egypt and the enthusiasm of his university teachers. Through a fascinating slide presentation, we saw the young Dr Long roughing it in a location which was alternately bitter cold and stifling hot.

Gimpsing the shards of broken pottery or the surprisingly modern interior decorations of a collapsed residence, our Year 7s slowly but surely became infected by the history bug. In learning about the past, our young historians were learning about themselves and, most importantly, learning the ways life might pan out in the future.

Simon Hughes

Head of Humanities