Learning for Retention

Mrs. Lakshmi Mohan - Deputy Principal

Learning for Retention

Mrs. Lakshmi Mohan - Deputy Principal

With our current senior ATAR phase of learning and assessment, it becomes imperative that we gear our students towards “learning for deep understanding and sustained content retention”. This is not only relevant for the senior years of study but also as important in the middle and junior years, for it is in these phases of schooling that the foundations for successful and engaged learners are established.

To ascertain optimal strategies that foster learning for deep understanding and retention, it is important to understand the operations of the human brain, particularly the processes associated with memory formation and holding.

The human brain is a learning machine. It is our memory bank and carries out the processes of encoding, storing and retrieving experiences and knowledge. Whilst there are several different types of memories as shown in Figure 1, what we typically think of as memory is Explicit Memory or conscious memory. This can be divided into two types: Episodic Memory which are events that have happened in life, and Semantic Memory, which are retained facts and general knowledge.

Figure 1: Memory

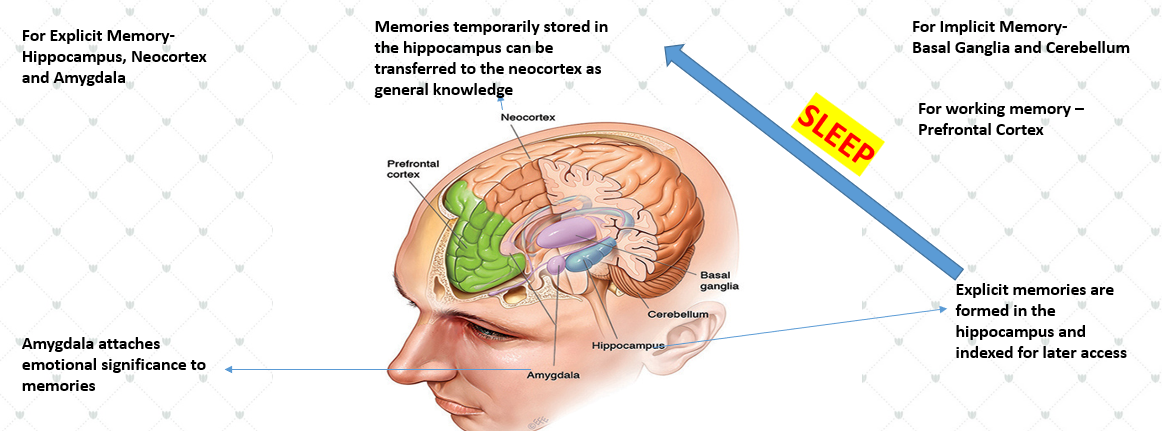

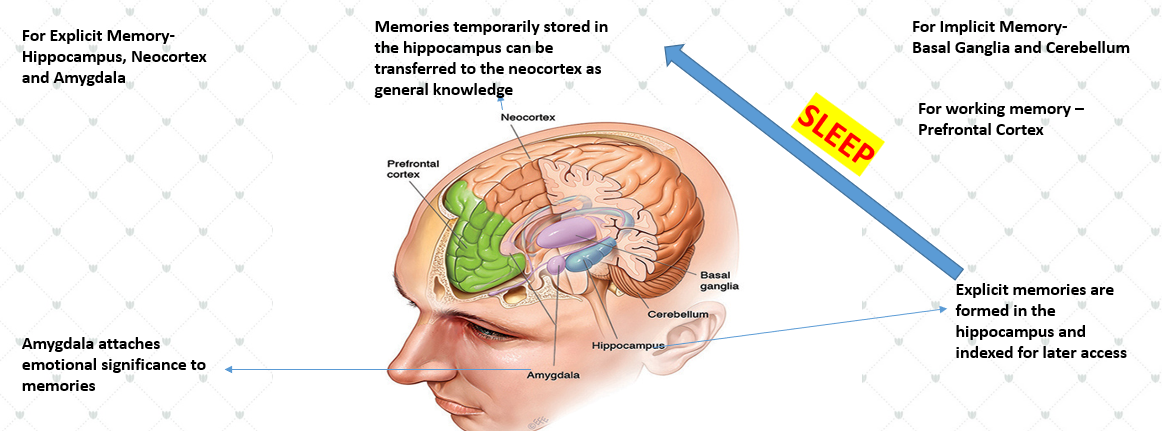

Memories are not stored in just one part of the brain. Different types are stored across different, interconnected regions. For explicit memory there are 3 important areas of the brain: the Hippocampus, the Neocortex and the Amygdala. The hippocampus is where memories are formed and indexed for later access. The neocortex is a sheet of tissue that forms the outer surface of the brain. Over time, information that is temporarily stored in the hippocampus can be transferred to the neocortex as general knowledge. Researchers think that this transfer from the hippocampus to the neocortex happens during sleep. While we sleep the hippocampus and neocortex take part in a carefully choreographed interaction during which the hippocampus replays recent events. The same neurons, or nerve cells, active in the hippocampus during an experience become activated again during deep sleep. This occurs repeatedly, helping to update the neocortex about what needs to be stored. So, if we are not getting enough sleep, we are not letting our brain consolidate memories. The amygdala attaches emotional significance to memories. This is particularly important because strong emotional memories are difficult to forget. The permanence of these memories suggests that the interactions between the hippocampus, amygdala and the neocortex are crucial in determining the stability of a memory, that is, how effectively it is retained over time.

Figure 2: Formation and storing of memories

In the brain, different neurons are constantly drifting in and out of action as they drive our thoughts or perceptions. A memory is a reactivation of a specific group of neurons. Synaptic plasticity refers to the persistent changes in the strength of connections- called synapses- between brain cells. These connections can be made stronger or weaker depending on how often they have been activated in the past. Active connections tend to get stronger, while inactive ones get weaker. Changing the strength of existing synapses, or even adding new ones or removing old ones, is critical to memory formation. Reinforcing a brain neuron strengthens it, like adding strands into a rope where each strand thickens the whole and adds strength to the final product. Neuroscientists like to say, “use it or lose it,” meaning that without practice and repetition, you’ll forget what you’ve learned.

Figure 3: Synaptic plasticity

There is also evidence that another type of plasticity could be important for memory. In some parts of the brain, including the hippocampus, brand new neurons can be created in a process called Neurogenesis. Neurogenesis is crucial when an embryo is developing, but also continues in certain brain regions after birth and throughout our lifespan. In Humans, amongst other things, exercise has shown to increase the volume of the hippocampus, suggesting that new neurons are being created and hence resulting in an improved performance in memory tasks. Eating a healthy diet is strongly associated with good general brain health and stronger brain function. In addition, there are some specific foods or supplements that have evidence of increasing neurogenesis such as flavonoids, found in blueberries and cocoa, or curcumin, found in the turmeric spice.

Figure 4: Neurogenesis

Memory formation can be compared to the formation of a foot pathway across a patch of grass as seen in Figure 5. The more the grass is trampled along the path as people walk through, the clearer the path becomes, and the easier the path becomes to follow. Similarly, in the brain, the more a neural pathway is activated, the stronger the synaptic connections become. The brain is a lot like a group of muscles, using them makes them stronger. Today we add to what neuroscientists have historically said (use it or lose it) to say, “Use it and grow it.” Practice and repetition not only grow your abilities, but your actual brain as well. So, it becomes important to “Revisit and Revise”.

Figure 5: Memory Pathways

In addition to getting enough sleep, regular exercise, eating a healthy and balanced diet and revisiting work, there are a number of other strategies that have also shown to enhance student learning and retention, including:

Distractions include mobile phones, social media, television, etc. Multitasking activates inhibitory networks in the brain. During multitasking it has been suggested that the brain is rapidly switching between tasks rather than doing them simultaneously. Research has also shown that chronic multitasking impairs both long- term and short- term memory.

Recall deepens memory formation. Doing quizzes or forcing oneself to actively recall information is linked to deeper memory formation than compared to when we passively read notes.

For long term memory and retention, research has shown that spacing study sessions apart is far more effective than when information is learned in one long session. Spaced repetition allows information retrieval over time. This strategy engages learners to review around the time just prior to when they are most likely to forget the material.

Engaging with revision material that combines different types of practice questions (multiple choice, short answer, simple recall, problem-solving, extended response, etc) from a range of syllabus topics is beneficial. Mixing up the practice of several interrelated skills can boost performance in the long run. This is called interleaving.

The brain’s visual and auditory processing centres are located in distinct regions and activated separately when we see images and hear words. So, while multitasking is detrimental to learning, research has found that processing images and spoken words simultaneously can boost memory and learning.

Choosing pen and paper note taking over typing is recommended. Writing something important down typically requires more effort and takes longer than typing, which forces the brain to fully engage with the material and this gives it a little longer to become etched in memory.

Creating rhymes, code words, etc while committing facts to memory. Mnemonics help form associations between content we want to remember. These associations are strengthened neural pathways formed by synaptic plasticity, so that when we think of the mnemonic, we more easily recall the content.

Breaking down information on a topic into smaller chunks. Evidence suggests that the optimum number of information "chunks” the human brain can hold in the short term is seven.

Taking opportunities to explain concepts to peers. Learners retain 90% of what they learn when they teach someone else. When we teach others, there is a high possibility that we may make mistakes, and when we run into difficulty and start to make mistakes, we must learn how to correct the mistake. This forces the brain to concentrate. Real learning comes from making mistakes.

Short 10-minute breaks have been shown to boost learning retention by up to 20 percent.

Using our voice more to encourage retention. If we want to retain something we have read, we will have a better chance of doing so if we read it out loud. When we read something out loud, it becomes more distinctive because we end up with a memory of both reading the words and hearing them spoken out loud. By saying things out loud repeatedly, our brain works to cement what has been said into our memory more efficiently.

To summarise, the following tips are recommended for our learners: