Canteen News

Canteen news.

Justine has recently had complex major knee surgery and is recovering at home.

We wish her all the best with her recovery.

During her absence, we have recognized how lucky we are to have a canteen, and such a wonderful chef.

The canteen will open in term two, at a date to be confirmed.

HOT CROSS BUNS

https://www.taste.com.au/recipes/traditional-hot-cross-buns-2/hpbp2oed

- 490g (3 1/4 cups) bread & pizza plain flour, plus extra, to dust

- 170g (1 cup) sultanas

- 2 tbsp mixed peel

- 2 tbsp caster sugar

- 1 tsp (1 sachet) dried yeast

- 1 tsp mixed spice

- 1 tsp ground cinnamon

- 1 tsp ground nutmeg

- Large pinch of salt

- 250ml (1 cup) warm milk

- 50g butter, melted, cooled

- 1 egg, lightly whisked

- 40g (1/4 cup) plain flour

- 2 tbsp cold water

- 70g (1/3 cup) caster sugar

- 80ml (1/3 cup) cold water

- Cross paste

- Glaze

- Step 1

Brush a baking tray with melted butter. Combine the flour, sultanas, mixed peel, sugar, yeast, mixed spice, cinnamon, nutmeg, and salt in a large bowl. Stir to combine. Make a well in the centre.

The recipe above is taken from the Taste website.

The Interesting Story of the Hot Cross Bun

“Hot Cross Buns! Hot Cross Buns! One a penny, two a penny, Hot Cross Buns! If you've no daughters, give them to your sons. One a penny, two a penny Hot Cross Buns!”

Excerpted from The Bread Baker’s Guild “Breadlines”

By Mitch Stamm and Kate Goodpaster

Nations, cultures, and religions include bread as an integral component of religious and secular observances. The bread is typically enriched and may contain dairy, eggs, sweeteners, and inclusions. Hot cross buns have been synonymous with Easter celebrations since they appeared in 12th century England. Interestingly, hot cross buns pre-date Christianity, with their origins in paganism. Ancient Egyptians used small round bread topped with crosses to celebrate the gods. The cross divided the bread into four equal sections, representing the four phases of the moon and/or the four seasons, depending on the occasion. Later, Greeks and Romans offered similar sweetened rolls in tribute to Eos, the goddess of the morning, and to Eostre, the goddess of light, who lent her name to the Easter observances. The cross on top symbolized the horns of a sacrificial ox. The English word bun is a derivation of the Greek word for ceremonial cakes and bread, "boun".

In the Middle Ages, home bakers marked their loaves with crosses before baking. They believed the cross would ensure a successful bake, warding off the evil spirits that inhibit the bread from rising. This superstition gradually faded, except for marking Good Friday loaves and hot cross buns, only to be replaced by another one. This time the loaves and buns were hung from the ceiling like sausages. It was believed that the bread would never mould and would provide protection against evil spirits and illness until the following Good Friday when the loaves and buns would be replaced. In the event of illness, a portion of bread could be removed from its string and crushed to a powder, which was incorporated into the water for a therapeutic effect. During the same period, Jews hung bread and a container of water from the ceiling to ward off cholera. They believed its power was so strong that one loaf in one house would protect the community. To avoid detection, early Christians celebrated the resurrection of Christ at the same time of year as the pagan Spring celebration.

It was in the 12th century that an English monk decorated his freshly baked buns with a cross on Good Friday, also known as the Day of the Cross. The custom gained traction, and over the years, fruits and precious spices were included to represent health and prosperity. Spiced buns were banned when the English broke ties with the Catholic Church in the 16th century. However, by 1592, Queen Elizabeth I relented and granted permission for commercial bakers to produce the buns for funerals, Christmas, and Easter. Otherwise, they could be baked in homes. The bakers argued that a cross cut into a loaf or bun induced a more pronounced rise in the oven: an axiom then, and an axiom now.

Farmers began to place hot cross buns in their stored grain to distract mice and other pests, much the way shoofly pie was used by American housewives. By the early 19th century, the Bun House of Chelsea, famous for Chelsea buns, was the largest producer of hot cross buns. It remained so for over a century until the building was demolished. Once an English specialty, the buns’ popularity has become a seasonal staple around the world and is included in Le Coupe du Monde de la Boulangerie as one of the Breads of the World.

“One a penny, two a penny, hot cross buns! If you’ve no daughters, give them to your sons, And if you’ve no kind of pretty little elves, Why then good faith, e’en eat them all yourselves”

“One a penny, two a penny, hot cross buns! Butter them and sugar them and put them in your muns (i.e. mouths). Hot cross buns, hot cross buns! One a penny poker, two a penny tongs, three a penny fire shovel, Hot cross buns!”

Anzac biscuits

https://www.awm.gov.au/articles/blog/anzac-biscuits

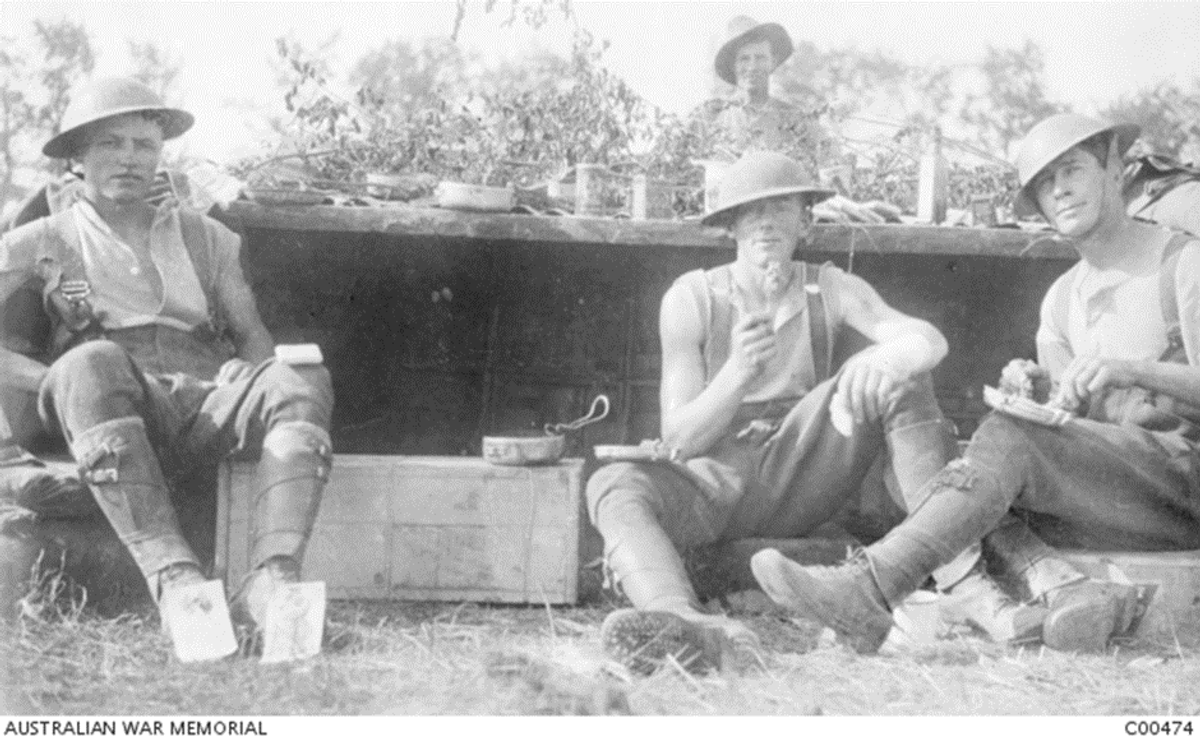

Every year, as ANZAC Day approaches, people become curious about ANZAC biscuits. Maybe it's because the thought of them is a delectable relief to the sombreness of that day and all that it represents. But it is easy to make mistakes about ANZAC biscuits, strangely enough. The biscuit that most of us know as the ANZAC biscuit is a sweet biscuit made from rolled oats and golden syrup. These must not be confused with that staple of soldiers' and sailors' rations for centuries, the hardtack biscuit.

To deal with these rather unpalatable objects first, hardtack biscuits are a nutritional substitute for bread, but unlike bread, they do not go mouldy. And also, unlike bread, they are very, very hard. On Gallipoli, where the supply of fresh food and water was often difficult to maintain, hardtack biscuits became notorious. So closely have they been identified with the whole Gallipoli experience that they are sometimes known as ANZAC tiles or ANZAC wafer biscuits.

Hence the confusion with the sweet biscuit.

There is actually nothing wafer-like about hardtack biscuits. Soldiers often devised ingenious methods to make them easier to eat. A kind of porridge could be made by grating them and adding water. Or biscuits could be soaked in water and, with jam added, baked over a fire into "jam tarts". Not at all like Mum used to make, but better than nothing.

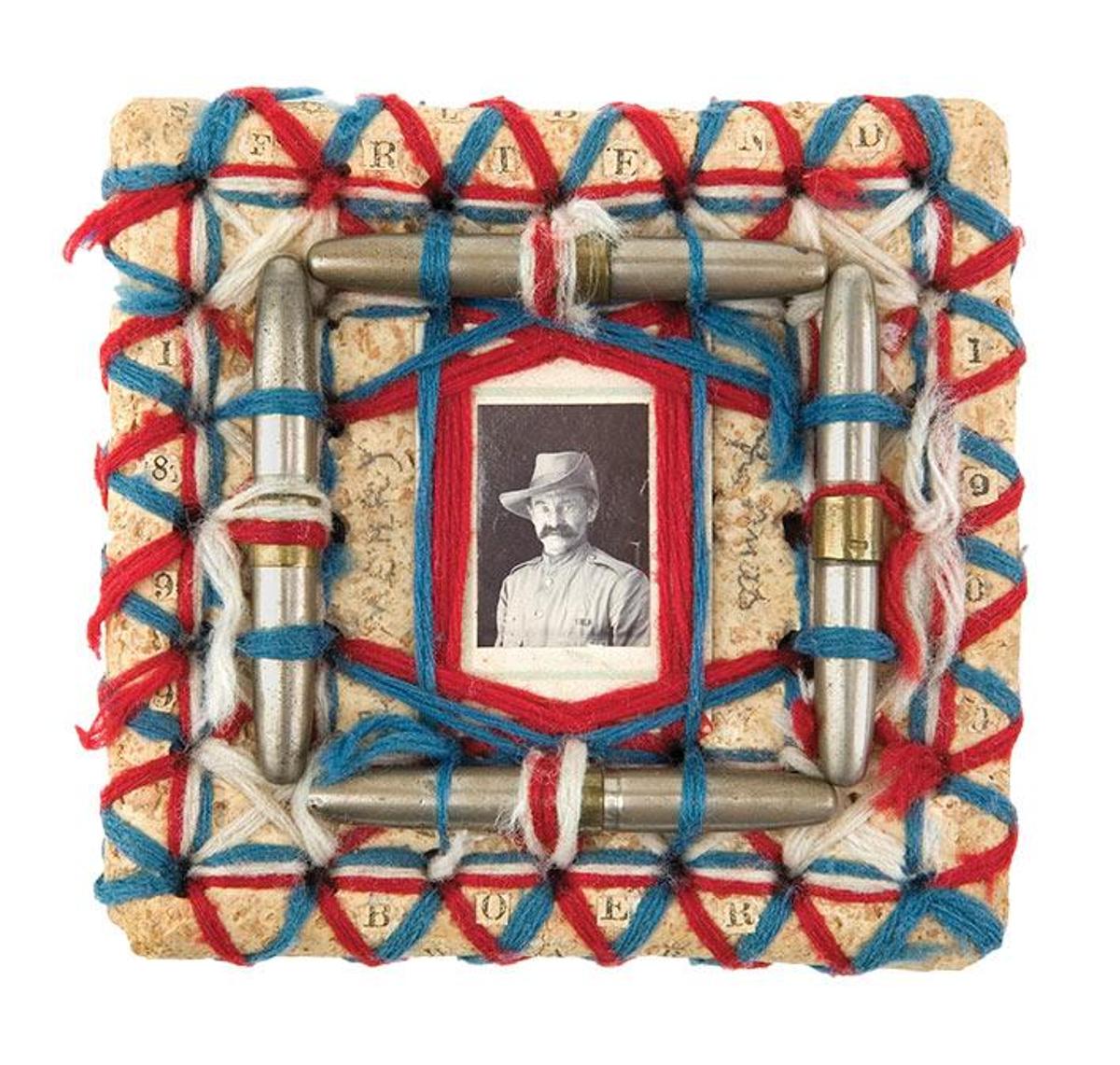

Strange as it seems, the Australian War Memorial holds in its collection a range of hardtack biscuits from the First World War. So durable are they, that soldiers used them not just for food, but for creative, non-culinary purposes. The texture and hardness of the biscuits enabled soldiers to write messages on them and send them long distances to family, friends, and loved ones.

Soldiers also used the biscuits as paint canvases and even as photo frames. One such biscuit features the use of wool and bullets to create a picture frame. Another was used as a "Christmas card" and had a tropical scene painted on it.

Christmas card made from army biscuits in 1900

"A small painted biscuit on which one side is painted an island scene in color. The other side is painted gold and in black are painted the words ‘Good Luck to YOU / FROM US AT”TOL” / WE’RE SENDING THIS / (WE’LL RISK IT) / XMAS CARDS ARE VERY / SCARCE SO WE / WROTE IT ON A BISCUIT’."

The origin and invention of the sweet ANZAC biscuit are contested. Conventionally it is an eggless sweet biscuit made from oats and golden syrup, but these sweet biscuits are not the same rations that were supplied to soldiers in Gallipoli.

From the 1920s onwards Australian recipe books nearly always included ANZAC biscuits but exactly how this recipe became identified with ANZAC, or the First World War, is unknown. They don't have the shelf-life of hardtack biscuits but they do last a reasonable amount of time, so it is possible that they became known as a suitable inclusion in parcels of small luxuries and comforts that families and charitable organizations used to send overseas to soldiers.

Making ANZAC biscuits is one tradition that Australians use to commemorate ANZAC day. Everyone has their favorite recipe and there are countless arguments over whether they should be served crunchy or soft.

Although the sweet Anzac biscuits are far more enjoyable to eat than their hardtack counterparts it is safe to say that, with the creativity of the First World War soldiers, the Anzac tile biscuits had far greater uses than just for eating.

ANZAC BISCUIT RECIPE

https://www.taste.com.au/recipes/anzac-biscuits/cc4e2031-8b63-48e7-8eff-b2637f472180

- 1 1/4 cups plain flour, sifted

- 1 cup Rolled Oats

- 1/2 cup caster sugar

- 3/4 cup Desiccated Coconut

- 150g unsalted butter, chopped

- 2 tbsp golden syrup or treacle

- 1 1/2 tbsp water

- 1/2 tsp Bicarbonate Soda

- Step 1 - Preheat oven to 170C. Place the flour, oats, sugar, and coconut in a large bowl and stir to combine.

- Step 2 - In a small saucepan place the golden syrup and butter and stir over low heat until the butter has fully melted. Mix the bicarb soda with 1 1/2 tablespoons water and add to the golden syrup mixture. It will bubble whilst you are stirring together so remove it from the heat.

- Step 3 - Pour into the dry ingredients and mix together until fully combined. Roll tablespoonfuls of mixture into balls and place on baking trays lined with non stick baking paper, pressing down on the tops to flatten slightly.

- Step 4 - Bake for 12 minutes or until golden brown.