Unit 3 Sociology Ethnicity Report

By Lucia Carlon-Tozer (11 Riley)

Unit 3 Sociology Ethnicity Report

By Lucia Carlon-Tozer (11 Riley)

Background Information

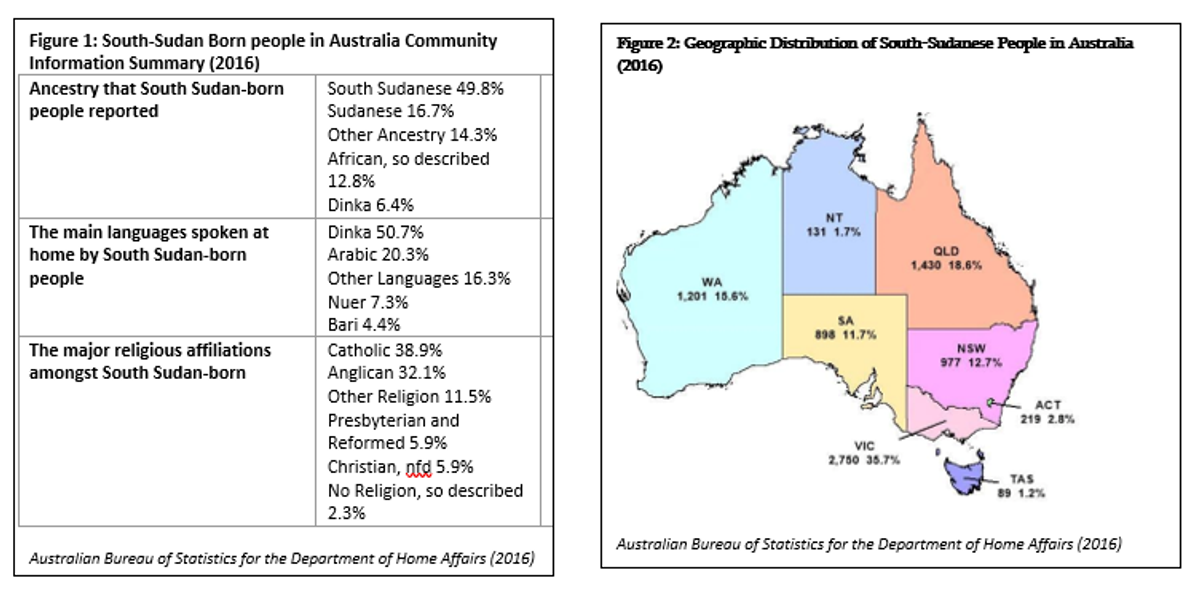

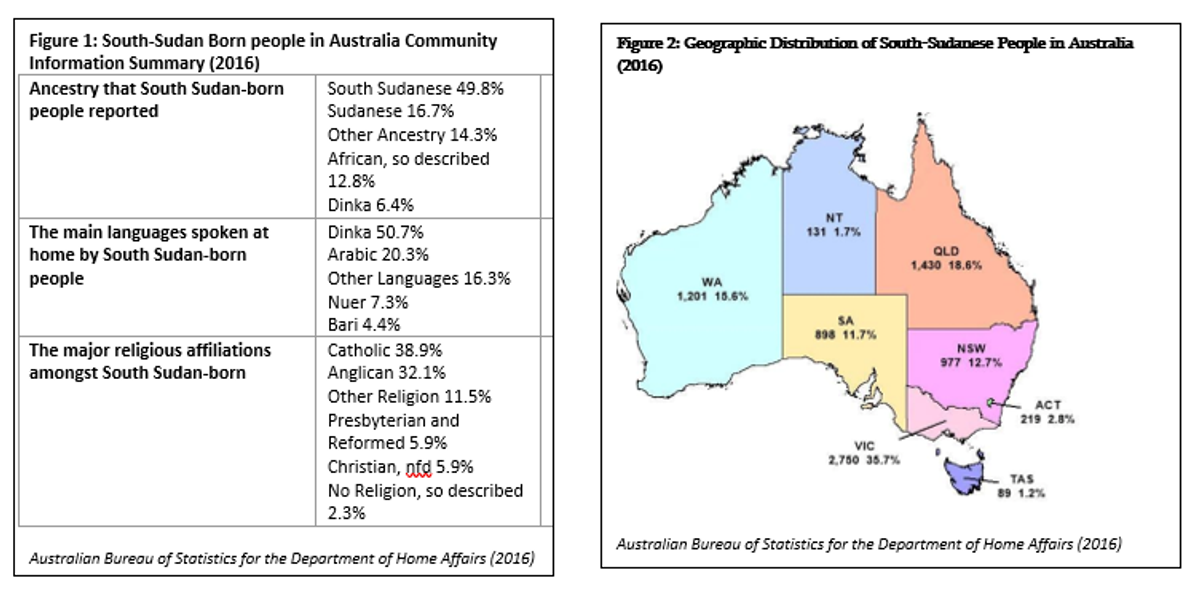

South Sudan (officially the Republic of South Sudan) is located in east-central Africa and is the most recently formed country in the world. The Republic of South Sudan gained independence from the Republic of Sudan on 9 July 2011 after more than 50 years of political struggle. Drought, famine, and war resulted in large numbers of South Sudan-born refugees leaving for neighbouring countries, with many resettling in Australia. The majority (over 65%) of South Sudanese arrivals in Australia peaked between 2002 and 2007 (Department of Home Affairs, 2018). Most arrived in Australia via Egypt, Kenya, Uganda and Ethiopia, living in refugee camps in these countries, after having fled drought, famine and war in South Sudan (Cultural Atlas, 2016). Figure 1 showcases the major diversity throughout the South Sudanese Australian community, with the major ancestry reported by South Sudan-born Australians as South Sudanese 49.8%, the most commonly spoken language was Dinka 50.7%, and the major religious affiliation amongst South Sudanese born Australians was Christian 82.8% (Catholic 38.9%, Anglican 32.1%, Presbyterian and Reformed 5.9%, and Christian nfd 5.9%). According to the 2016 Australian Housing and Population Census, 7,699 Australian residents were born in South Sudan (this statistic is discussed more in the next section). As seen in Figure 2, distribution by State and Territory demonstrated Victoria had the largest number of South-Sudanese people with 2,750 followed by Queensland (1,430), Western Australia (1,201) and New South Wales (977).

South Sudanese Identity

The national identity of South Sudan is still newly emerging as it is the youngest country in the world. Most South Sudanese people share a cultural connection based on their common practice of Christianity (as seen in Figure 1), and the experience of struggle and liberation from North Sudan (Cultural Atlas, 2016). South Sudanese tend to feel more cultural affiliation and loyalty to their tribal and ethnic groups rather than allegiance to the nation (Cultural Atlas, 2016). According to the 2016 Australian Housing and Population Census, 7,699 Australian residents were born in South Sudan (Census, 2016). However, this census data does not necessarily reflect their true community affiliations. Due to South Sudan forming in 2011, the majority of people who identify as South Sudanese were technically born in the ‘Republic of Sudan’, hence, they list ‘Republic of Sudan’ as their birthplace and consequently get categorised as (North) Sudanese. South Sudanese Australian community leaders estimate that there are actually over 20,000 people who identify as South Sudanese in Australia (Cultural Atlas, 2016). Most South Sudanese people identify with one another based on their African ethnic heritage and Christian beliefs, as these are defining factors that differentiate them from the (predominantly Arab Muslim) Northern Sudanese (Cultural Atlas, 2016). South Sudanese Australians tend to identify in a variety of ways. When questioned whether she felt ‘Australian’ on SBS’s ‘Where Are You From?’, despite living in Australia for most of her life, Journalist Margaret Nyakan Agoth answered, “I do and I don’t, because I could call myself Australian and then someone’s gonna be like ‘where are you from?’ You can’t hide this, you can’t hide your skin colour, so you will always be pointed out” (Where Are You Really From? 2019).

Non-Material Culture of South-Sudanese People

Non-material culture refers to the non-physical creations and ideas of a society, such as knowledge, values, beliefs, languages, symbols, and social norms, that are transmitted across generations. Many South Sudanese groups mark the stages or events in the individual's life cycle, including birth, puberty, marriage, and death with the non-material cultural practice of ritual and ceremonial practices. Facial scarring and tattooing, for example, are methods of ritual adornment that are Ancient South Sudanese customs still being practised today. Men of the Dinka tribe scar their faces with three parallel lines across the forehead in a rugged display of courage to the tribe (Anderson, 2011), while Dinka women have their entire bodies scarred in patterns that reveal their marital status and the number of children they have had (Everyculture.com, 2012).

Humanitarian worker, Emily Sloane said facial scaring “Is a chance for youths to demonstrate their bravery in front of their peers and elders…Anyone who cries or resists the process loses a great deal of face” (Anderson, 2011). For boys in the Dinka tribe, receiving their scars around adolescence marks the transition to manhood, when they begin to take on the responsibilities of the other men in the nomad tribe (Anderson, 2011). However, it’s important to note that under Australian law, the customs of scarification and tattooing are only legal when the person is over 18 and has given their consent for it (Cultural Atlas, 2022). Due to this age barrier, it is illegal for South-Sudanese Australians to practice sacralization to mark a significant point in the life cycle for young people, puberty.

Dance is an integral part of the non-material culture of South Sudanese people. South Sudan has thousands of cultural dances including the traditional dances of the Dinka people that play an important role in Dinka culture. Dinka people view the animal as the highest form of wealth, and the cow has always been the focus of their culture, as Cattle stood at the heart of virtually every important tradition and ceremony in Dinka life, including honouring it in dance (Buckely, 2022). A Dinka tribe member said in an interview the BBC Radio's Home Service for Schools, “Dinka dancing is not like your dancing, just walking about arm in arm. We have to stamp and jump and shout-we pretend that we are bulls, and we hold our arms like the horns of a bull.” (Lienhardt, 1997). The Dinka tribe member also mentioned that men “sometimes put markings on them with coloured powder, to make themselves look like their oxen” when performing their tribal dance (Lienhardt, 1997). As seen in figure 3, within Braybrook Victoria, there is the Dinka Traditional Dance Group, made up of young people who are working in collaboration to preserve the remarkable culture and tradition through dancing their native Dinka dance (dinka traditional dance group, 2022). The group performs at community events and private functions, educating and promoting their cultural dance stating, “we want to bring a better understanding of our culture and tradition by embracing our identity” (Dinka traditional dance group, 2022).

Material Culture of South-Sudanese people

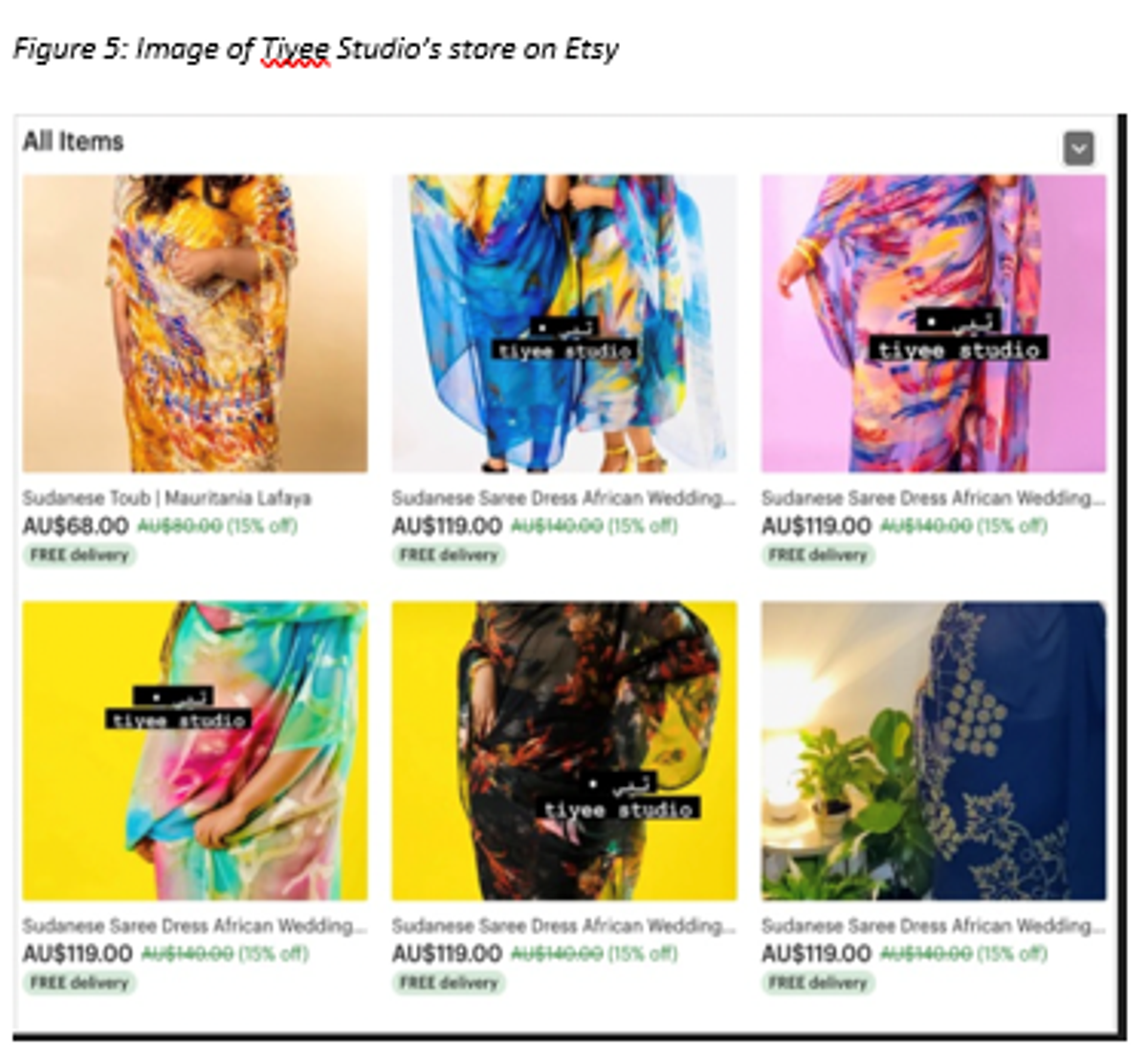

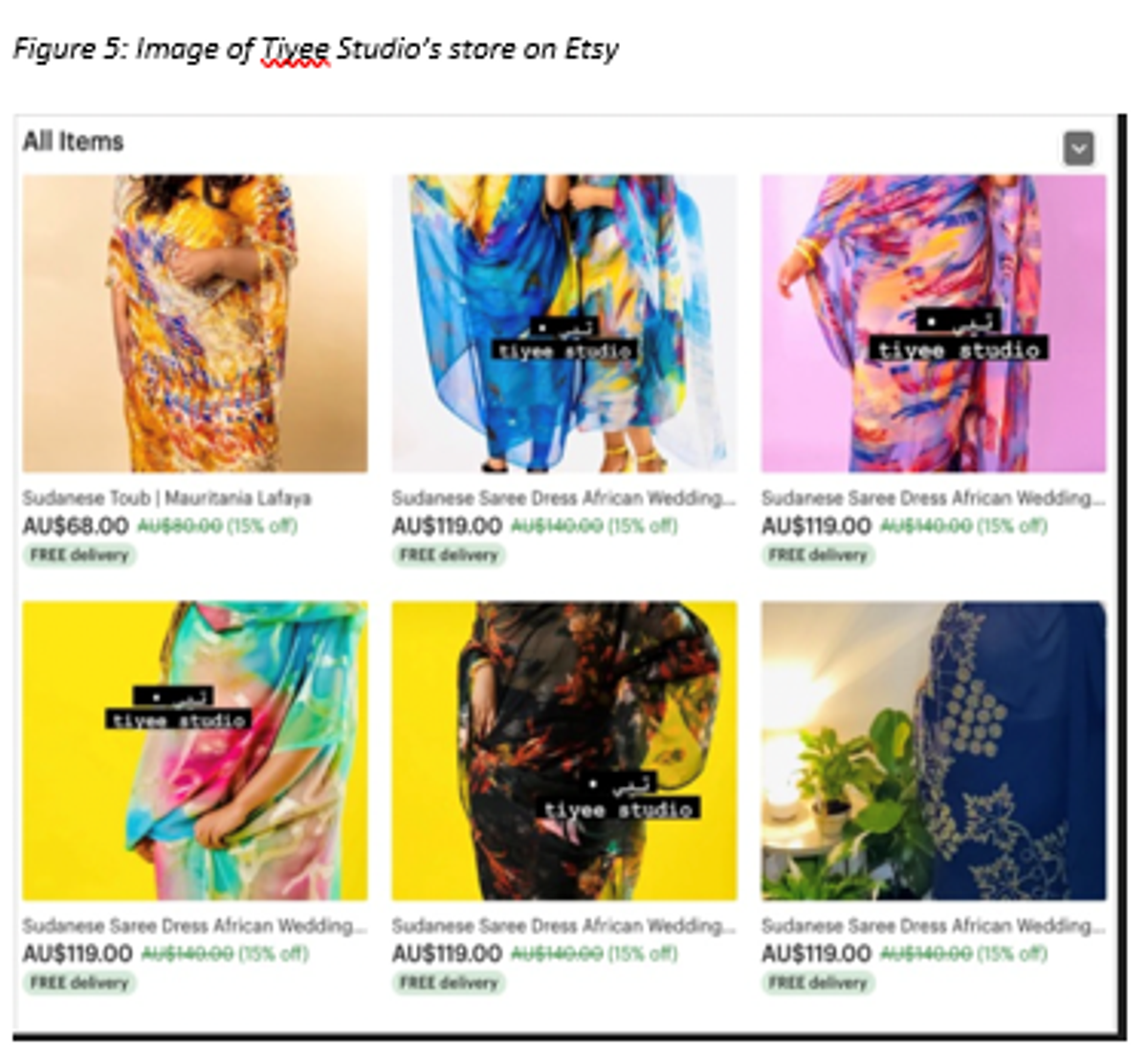

Material culture refers to the physical objects, artefacts, resources, and spaces of a society which are passed onto subsequent generations. An example of material culture within the South-Sudanese community is the national costume of Sudanese women called “toob”. As seen in figure 4, a Toob is a long wrap-around cloth worn on top of a shirt and skirt/trousers, that covers the body entirely. It can be made from cotton, satin, polyester, jersey, denim and other fabrics of any colour or pattern (Nationalclothing.org, 2015). Traditional clothing of the toob is very important for Sudanese women to display status, social class, or what clan or tribe they belong to. Girls wear their first toob at the age of 12, and women should have at least several toobs for different occasions like shopping, work, or a wedding (Nationalclothing.org, 2015). Due to Islamic traditions influencing norms of dress in South Sudan, many women cover their body with a toob and other clothing, leaving only their feet, palms and face uncovered. Within Australia, it is relatively hard to find traditional a toob in stores, however, South-Sudanese Australians can purchase toob’s online. For example, on Etsy, there is a seller called ‘Tiyee Studio’, a small business based in Australia selling Sudanese and East African Fashion, including the toob (see figure 5).

Another example of material culture of South-Sudanese people is African Okra Soup with Kombo, a specialty of the Kakwa tribe from Yei, South Sudan (Mogga, 2017). As seen in figure 6, it is a vegetarian, low-calorie soup free of gluten, often served prior to your main course or as a side dish (Mogga, 2017). The special ingredient in the African Okra Soup is the traditional salt Kombo, which gives a distinctive taste and smell and is a strong alkali solution that chemically contains a mix of sodium hydroxides, potassium phosphates and potassium carbonates (Mogga, 2017). In South Sudan and many parts of Africa, Kombo is homemade by running

water through ashes (Mogga, 2017). Within Australia, South Sudanese people can find African Okra Soup with Kombo from the Sudanese Mothers Coalition of Victoria, who for the last decade, have delivered African Okra Soup with Kombo from their Sunshine West kitchen to households across the city (Silva, 2020).

Cultural activities of South Sudanese People

A cultural activity distinctive to the South Sudanese is the practice of Christianity which differs, in specific ways, from Western Christian tradition. South Sudanese people generally attend church services more frequently, up to three times a week as opposed to once every Sunday (Cultural Atlas, 2016). Many South Sudanese Christian churches also facilitate a unique practice called ‘overnight’ whereby people go to a church service for 24 hours or more at a time, sometimes this prayer session lasts for days, with people sleeping and fasting in the church. (Cultural Atlas, 2016). Some see Church as a cathartic experience in which people get closer to God to the point of euphoria. This shouting and dancing provide emotional support for South Sudanese migrants that have recently migrated to Australia (Cultural Atlas, 2016). There are many places within Australia for South-Sudanese Australians to practice their Christian faith in Australia, these are mentioned within the enablers section.

Weaving is an integral part of South Sudanese material culture, weaving baskets, food covers, ceremonial mats and hangings has traditionally been the preserve of women in South Sudan (Women’s literacy in Sudan, 2019). Traditional Sudanese shopping baskets, or gufaaf are made from palm and doum tree fibres, both plentiful and sustainable resources within South Sudan (Women’s literacy in Sudan, 2019). Weaving, specifically basket-making, is both an art and a skill, often taught by grandmothers to their daughters and granddaughters. Within Australia, there is a Bendigo-based group called the ‘White Nile women's group’, who create woven and beaded items together, selling them to the local Bendigo community (see figure 7). This group brings together South Sudanese women from different African dialects, including Dinka, Nuer and Achol ((Gibson, 2021).

Rebecca Wuor, who speaks the Nuer and Dinka dialect, says, "When I came back to Australia I remembered how I used to do the weaving with my mum, and then I was like, 'Let me have a try of what my mum used to do back in the day”, "It's our culture, so that's why I find it important to keep on doing the activities that I do in Bendigo.” (Gibson, 2021). In South Sudan, many of these groups are in conflict, but in regional Victoria, they learn to create side-by-side and share their collective African culture. (Gibson, 2021). Wuor stated that "We can't forget our culture. We need to be together and, we need to make together, to feel like Sudanese women" (Gibson, 2021).

Barriers experienced by South Sudanese Australians

Figure 8: Peter Dutton on Sydney radio station 2GB

"people are scared to go out to restaurants of a night-time because they are followed home by these gangs..”

"But the short answer is that, if people haven't integrated, if they are not abiding by our laws, if they don't adhere to our culture, then they are not welcome here." (Hunter and Preiss, 2018).

A significant barrier[1] for the South Sudanese Australian communities is being the target of intolerance and hostility within Australian media reporting. Within the Australian media, there is a disproportionate amount of attention focusing on South-Sudanese Australians, specifically with the so-called ‘African gang’ problem in Melbourne, perpetuating the stigma that all South Sudanese people are violent criminals. As seen in Figure 8, Home Affairs Minister Peter uses media representation to demonstrate racist attitudes, reflecting the outdated ethnocentric policy of Assimilation (1940s – late 1960s), rather than the current policy of Multiculturalism (1975-present). Father Daniel Gai Aleu, at Holy Apostles Anglican church in Sunshine, said with this constant hostility towards the South Sudanese within the media, “Even as a priest I feel insecure,” when he goes to the supermarket, Aleu says other shoppers will “call the security guy and say, ‘look, this is a Sudanese’, and they will follow me”. He states, “I can say I’m an Australian, but my colour only betrays me,” he says. “What can I do?” (Henriques-Gomes, 2018). Despite this ethnocentric belief spread throughout the media, Victoria’s crime statistics agency stated that in 2017, South Sudanese people comprised only 1.0% of the offender population, in contrast to the Australian-born people in Victoria making up 71.7% of the offender population (Henriques-Gomes, 2018). The media hold significant power to shift public awareness and perpetuate negative social attitudes, therefore creating destructive links between race and behaviour, spreading social attitudes of intolerance and prejudice, and ultimately leading to a decreased feeling of belonging for many South-Sudanese Australians.

South Sudanese people may face barriers within families, struggling to adjust to the social structure and norms in Australia that challenge traditional South Sudanese family roles. The basic household structure for families is traditionally large and multigenerational, with people generally trying to have as many children as possible, sometimes up to 20 (Cultural Atlas, 2016). The average South Sudanese household usually consists of three generations, the eldest couple, their sons, sons’ wives, unmarried daughters, and their grandchildren (Cultural Atlas, 2016). This family structure can be a barrier for South Sudanese families in Australia, as the traditional family structure in Australia is a ‘nuclear family’, consisting of two parents and traditionally, two children.

Figure 9: Cost of two children over their lifetime

A 2013 report by the National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling, at the University of Canberra, finding the cost of raising two children in a typical middle-income family in Australia was $812,000, almost double the cost in 2002 ($448,000) (Lawrence, 2017) .

As seen in figure 9, the cost of raising only two children in Australia is $812,000, highlighting there is a significant economic barrier for South Sudanese families to afford to raise many children, as well as the extended family. Gender roles are also rigidly defined in South Sudan, the man is the breadwinner and the decision-maker, while females are the housemaker and child-bearer (Cultural Atlas, 2022). However, Doctor Santino Ding who runs parenting workshops for south Sudanese families in Australia, explains the change in family structure with “many south Sudanese families here (Australia) are female-headed households, as widows with children were often prioritised for refugee resettlement” (ABC Four Corner’s, 2022). He states there is a significant barrier in, “lacking male role models in the family is the major contributing factors, back home for instance if you don’t have the husband in the house, the uncle would be there other family other relatives. But in Australia you get confined in your own house you don’t have much support around” (ABC Four Corners, 2022). Not only is there a role reversal within gender roles, but there is also a role reversal within the family where children are very good at English and they understand the Australian system, making the parents feel powerless as they do not share that same understanding (ABC Four Corner’s, 2022). Polyamory[2] can also occur within family structures, amongst all socioeconomic backgrounds in South Sudan (Cultural Atlas, 2016). However, there is a political barrier as polygamy is illegal in Australia as it entails the crime of bigamy, which is defined as entering into a marriage with someone while already being legally married to another (Pullos Lawyers, 2020). Not only is polygamy illegal in Australia, it is also not supported via social attitudes, as it is seen as perpetuating a patriarchal form of gender inequality and risking women’s social, emotional, and economic wellbeing. Therefore, South Sudanese Australians are unable to practice this element of their culture, leading to a decreased sense of belonging.

Enablers experienced by South Sudanese Australians

Australia’s multicultural policy is both a social and political enabler[3] that encourages South Sudanese Australians to continue to celebrate important customs and traditions, consequently increasing a sense of belonging. Multiculturalism is the third phase in the evolution of Australia’s public policies on cultural diversity and migration. The multicultural policy (1975 to current) recognises the challenges that migrants face and accepts and celebrates migrant culture as a part of Australian heritage. It enables and encourages migrants to practice their cultural heritage within Australian society, free from persecution, and allows migrants to adopt Australian customs at their own pace (Babelja, Rentos, Solis, 2018). The current multicultural policy is founded on four central principles as seen in figure 10, which seek to celebrate cultural diversity, commit to an inclusive society, respond to the needs of a culturally and linguistically diverse nation of people, recognizing the economic prosperity multiculturalism has created in Australia and do not condone intolerance or discrimination (Babelja, Rentos, Solis, 2018). The multicultural policy has allowed South Sudanese Australians to continue practising their culture, for example, the Dinka Traditional Dance Group continues to practice South Sudanese dance styles. Similarly, Tiyee Studio is able to sell South Sudanese clothing throughout Australia, and the Sudanese Mothers Coalition of Victoria is able to deliver Kombo throughout Victoria, as well as the White Nile women's group in Bendigo within the Cultural Activities section, practising and selling weaving from South Sudan. The multicultural policy enables South-Sudanese people to practice their culture, allowing them to share their culture freely by protecting cultural expression through law, allowing an increase in social awareness of South Sudanese culture, spreading tolerance and acceptance leading to an increased sense of belonging and inclusion in Australian society.

Christianity is a significant enabler to belonging and inclusion for South Sudanese Australians within society. Referring to figure 1, the major religious affiliation amongst South Sudanese born Australians was Christian 82.8% (Catholic 38.9%, Anglican 32.1%, Presbyterian and Reformed 5.9%, Christian, nfd 5.9%). The most common overall reported religion in Australia is Christianity, 52% (Catholic, 22.6%, Anglican 13.3%, and Other Christian 16.3%) (Abs.gov.au, 2016). Christianity is the dominant religion within Australia, therefore social attitudes support this custom and tradition, allowing South Sudanese people to practice their faith of Christianity free from discrimination. Christianity plays a very strong role in providing a coping strategy for many South Sudanese, therefore being able to practice leads to an increased sense of belonging and inclusion. Due to Christianity being the norm in Australia, there is already existing infrastructure to practice Christianity, as well as specific south Sudanese churches established in which they can speak their own language within church ceremonies. For example, in Toowoomba Queensland, there is St. James Anglican Church, a predominantly South Sudanese congregation. St. James church offers services that celebrate in Dinka only, allowing the South-Sudanese community to practice Christianity within their traditional language (St. James' Services 2019). South-Sudanese journalist and member of the St. James Parish, Margaret Nyakan Agoth stated that “The church is like our hub, it’s like a place where they come to clear their mind, it’s like the only place where everyone can meet” (Where Are You Really From? 2019). When asked how important the church was in terms of her culture she stated, “It’s a way for us to keep our culture alive and also keep our language alive and teach our children” (Where Are You Really From? 2019). The Christian faith is accessible and easy to support the religion and attend services allowing South Sudanese Australians to celebrate important Christian customs and traditions, majorly increasing a sense of belonging.

Bibliography

ABC Four Corner’s, (2022), Crime and Panic, ABC News. [online] Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/4corners/crime-and-panic/10467544 [Accessed 26 May 2022].

Abs.gov.au. (2016). Main Features - Religion Data Summary. [online] Available at: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/2071.0~2016~Main%20Features~Religion%20Data%20Summary~70#:~:text=Reflecting%20the%20historical%20influence%20of,religion%20in%202016%20(30%25). [Accessed 29 May 2022].

Anderson, T. (2011), ‘Sudanation- Sudan Facial Scarification’ [online] Available at: https://sudanation.wordpress.com/2011/05/03/sudan-facial-scarification/ [Accessed 26 May 2022].

Buckley S., (2022). washingtonpost.com: African Lives. [online] Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/inatl/longterm/africanlives/sudan/sudan.htm [Accessed 26 May 2022].

Cultural Atlas. (2016). South Sudanese Culture. [online] Available at: https://culturalatlas.sbs.com.au/south-sudanese-culture/south-sudanese-culture-south-sudanese-in-australia [Accessed 28 Apr. 2022].\

Community Information Summary Historical Background 2016 Census Geographic Distribution. (n.d.). [online] Available at: https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/mca/files/2016-cis-south-sudan.PDF.

Cia.gov. (2022). [online] Available at: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/south-sudan/ [Accessed 16 May 2022].

Babelja, Rentos, Solis, (2018), Sociology VCE Units 3 and 4 (2nd Edition)

dinka traditional dance group. (2022). About. [online] Available at: https://dinkatraditionaldancinggroup.weebly.com/about.html [Accessed 26 May 2022].

Department of Home Affairs (2016), Community Information Summary Historical Background 2016 Census Geographic Distribution. (n.d.). [online] Available at: https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/mca/files/2016-cis-south-sudan.PDF.

Everyculture.com. (2012). Dinka - Introduction, Location, Language, Folklore, Religion, Major holidays, Rites of passage. [online] Available at: https://www.everyculture.com/wc/Rwanda-to-Syria/Dinka.html [Accessed 26 May 2022].

Everyculture.com. (2012). Culture of Sudan - history, people, clothing, traditions, women, beliefs, food, customs, family. [online] Available at: https://www.everyculture.com/Sa-Th/Sudan.html [Accessed 16 May 2022].

Gibson B. (2021) ‘Bendigo’s White Nile South Sudanese women’s group bringing warring ethnic tribes together ‘- ABC News. (2021). ABC News. [online] 17 Feb. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-02-18/bendigo-white-nile-african-women-group-cultural-bonds/13145250 [Accessed 26 May 2022].

Henriques-Gomes, L. (2018). ‘It’s not safe for us’: South Sudanese-Australians weather ‘African gangs’ storm. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2018/jul/25/its-not-safe-for-us-south-sudanese-australians-weather-african-gangs-storm [Accessed 16 May 2022].

Hunter F. and Preiss B. (2018). Victorians scared to go to restaurants at night because of street gang violence: Peter Dutton. [online] The Sydney Morning Herald. Available at: https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/victorians-scared-to-go-to-restaurants-at-night-because-of-street-gang-violence-peter-dutton-20180103-h0cvu4.html [Accessed 26 May 2022].

Jimma, N. (2020), South Sudanese refugees on the challenges of making a new life in Australia ABC News. [online] 12 Jul. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-07-12/meet-south-sudanese-refugees-making-their-mark/12434498 [Accessed 16 May 2022].

Jeyaratnam, E. (2018). Twelve charts on race and racism in Australia. [online] The Conversation. Available at: https://theconversation.com/twelve-charts-on-race-and-racism-in-australia-105961 [Accessed 16 May 2022].

Lienhardt, G. (n.d.). DINKAS OF THE SUDAN. [online] Available at: https://www.anthro.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/anthro/documents/media/jaso28_1_1997_27_32.pdf.

Lawrence, E. (2017). ‘I say I have 10 kids and their jaws drop’. [online] couriermail. Available at: https://www.couriermail.com.au/news/queensland/big-families-on-why-they-have-so-many-children-and-how-they-cope/news-story/cf401e4e88602db7f770f9bc48d0ffcd [Accessed 26 May 2022].

Mogga N. (2017), ‘African Okra Soup with Kombo - Swala - Taste of South Sudan’ [online]. Available at: https://tasteofsouthsudan.com/african-okra-soup-with-kombo-swala/ [Accessed 26 May 2022].

Millar, B. (2018). Race panic drags Australia to new low: discrimination commissioner. [online] The Sydney Morning Herald. Available at: https://www.smh.com.au/national/race-panic-drags-australia-to-new-low-discrimination-commissioner-20180422-p4zb17.html [Accessed 26 May 2022].

Nationalclothing.org. (2015). National dress of Sudan. Men prefer loose-fitting robes and women use wrap-around cloths - Nationalclothing.org. [online] Available at: http://nationalclothing.org/africa/35-sudan/49-national-dress-of-sudan-men-prefer-loose-fitting-robes-and-women-use-wrap-around-cloths.html [Accessed 26 May 2022].

Pullos Lawyers. (2020). Polygamy in Australia: Are Overseas Marriages Recognised in Australia? [online] Available at: https://pulloslawyers.com.au/polygamy-in-australia-are-overseas-marriages-recognised-in-australia/#:~:text=Polygamy%20is%20currently%20illegal%20in,being%20legally%20married%20to%20another. [Accessed 26 May 2022].

Spaulding, J, ‘South Sudan | Facts, Map, People, & History’ Britannica. (2022). In: Encyclopædia Britannica. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/place/South-Sudan [Accessed 26 May 2022].

Silva K. (2020), ‘Kombo is more than just South Sudanese meal. For some in Melbourne, it’s been a lifeline’, ABC News [online] 11 Dec. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-12-12/kombo-south-sudanese-meal-a-lifeline-in-melbourne-during-covid/12971294 [Accessed 26 May 2022].

StJames' Services 2019, Anglican Parish of St James Toowoomba and St Annes Highfields, Anglican Parish of St James Toowoomba and St Annes Highfields, viewed 29 May 2022, <https://stjames.org.au/stjames>.

Team Africa, (2018). Traditional Dancing Styles from Sudan. [online] Portal To Africa. Available at: https://www.portaltoafrica.com/entertainment/sudan/traditional-dancing-styles-from-sudan [Accessed 26 May 2022].

TiyeeStudio (2022) Etsy Australia. [online] Available at: https://www.etsy.com/au/shop/TiyeeStudio?ref=simple-shop-header-name&listing_id=1166326744 [Accessed 26 May 2022].

Women’s literacy in Sudan. (2019). Weaving Brighter Futures. [online] Available at: https://womensliteracysudan.blog/2019/09/01/weaving-better-futures/ [Accessed 26 May 2022].

Where Are You Really From? 2019, Sbs.com.au, viewed 29 May 2022, <https://www.sbs.com.au/ondemand/program/where-are-you-really-from>.

[1] A barrier to belonging and inclusion in Australia’s multicultural society, is anything that obstructs, limits, or makes it difficult for an individual to group to feel safe and included in Australian society.

[2]Polygamous marriage in which the man can have multiple wives, usually two or three.

[3] An enabler to belonging and inclusion in Australia’s multicultural society is anything that encourages, promotes or makes it possible for an individual or group to feel safe and included in Australian society.