From the Desk of the Principal

Dear Parents and Carers, Staff and Students, and Friends of Mount Alvernia College,

This year we have had to focus on the concept of resilience in order to get through all of the interesting scenarios that the COVID–19 virus has raised.

I have been amazed at how our students have coped so well, given the changes to our daily lives that were needed. And I was asking myself why some people cope better than others, especially our students. This research article from the Alliance of Girls’ Schools seemed to answer some of my concerns.

Harvard University researchers say there is no such thing as a “resilience gene”

Issue 10/2020: June 17, 2020

According to a series of reports by Harvard University’s Centre on the Developing Child, including its 2020 paper, Connecting the brain to the rest of the body, many children develop resilience — the ability to overcome serious hardship — while others do not. For children who possess resilience, their health and development tips towards positive outcomes even when they face adversity or a serious threat. In contrast, under the same circumstances, children without resilience experience negative outcomes. Why is it that some children and adolescents are resilient despite great adversity while others appear to be stuck in a permanent state of heightened or 'toxic' stress?

Research has identified four factors that predispose children to positive outcomes in the face of adversity:

- having at least one stable, caring and supportive child-adult relationship

- feeling a sense of mastery (self-efficacy and perceived control) over life circumstances, including a belief that they can overcome hardships,

- possessing strong executive function and self-regulation skills which enable them to execute adaptive skills to cope effectively with difficult circumstances and manage their own behaviour and emotions, and

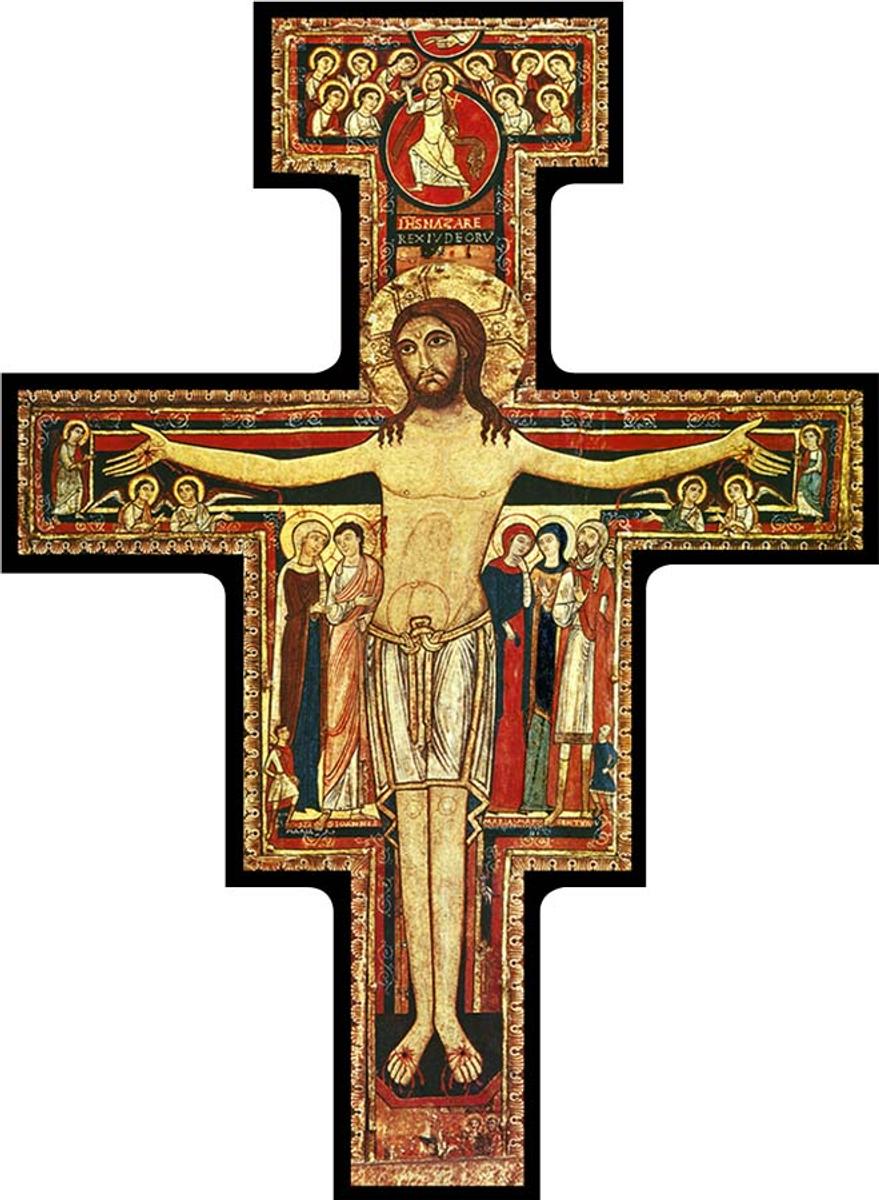

- the support of faith, hope, or cultural traditions to ground them when challenged by a major stressor or severely disruptive event.

Of these, the single most common factor is having at least one stable and committed relationship with a parent, caregiver, or other adult, such as a teacher or counsellor. These relationships buffer children from developmental disruption through providing the personal responsiveness, scaffolding, and protection that they need. Stable and caring relationships also help to build key capacities — including the ability to plan, monitor, and regulate behaviour — that allow children to adapt to adversity and thrive. “This combination of supportive relationships, adaptive skill-building, and positive experiences”, say the Harvard researchers, “constitutes the foundation of what is commonly called resilience.”

Fundamental to this is the recognition that not all stress is harmful. In fact, learning to cope with stress is critical for the development of resilience. 'Positive stress' — where children experience manageable levels of stress with the help of supportive adults — can be growth-promoting. From coping with a minor infection like a cold to failing an examination, children and adolescents regularly experience stresses that help them to grow and become stronger. “Over time, both our bodies and our brains begin to perceive these kinds of threats as increasingly manageable”, write the Harvard researchers, “and we become better able to cope with life’s obstacles and hardships, both physically and mentally.”

In fact, it is never too late to build resilience. Studies show that we can develop and strengthen resilience at any stage of life through regular physical exercise, stress-reduction practices, and programs that build executive function and self-regulation skills. Sport, exercise, and activities like mindfulness meditation can alter brain structure and function, as well as reduce the expression of pro-inflammatory genes. Programs that build skills in planning, organisation, cognitive flexibility, and other executive functions can also help children, teens, and adults cope with and adapt to adversity.

However, it is also important to acknowledge the existence of 'toxic stress' and the role it plays in some young people and adults finding it extremely difficult, or even impossible, to develop resilience. Indeed, there is a growing body of scientific evidence about the power of childhood stress to weaken brain architecture and damage lifelong health.

Children inherit about 23,000 genes from their parents but not every gene will work as designed. Experiences leave a chemical 'signature' on genes which determine if and how they are expressed. Positive experiences, such as supportive relationships and consistent routines, and negative experiences, including stress, malnutrition and exposure to toxins, can temporarily or permanently change the chemistry than encodes genes in brain cells.

Not only can this 'epigenetic modification' influence how structures like the brain, heart, and kidneys develop, but it can also impair a child’s future learning capacity and behaviour. Healthy development of the brain is influenced by 'serve and return' interactions between children and caring adults which help children’s stress responses return to normal baseline levels. In the absence of these interactions, a child’s stress response system may be activated over a prolonged or excessive period, leading to “physiological changes that can have a wear and tear effect on the brain”. Harvard University’s 2010 report on how gene expression can affect long-term development concludes that:

Repetitive, highly stressful experiences can cause epigenetic changes that damage the systems that manage one’s response to adversity later in life. On the other hand, supportive relationships and rich learning experiences generate positive epigenetic signatures that activate genetic potential.

Research shows that there may be ways to reverse certain negative changes and restore healthy functioning but, say the researchers, “the very best strategy is to support responsive relationships and reduce stress to build strong brains from the beginning”.

Even in situations of significant disadvantage or stress, supportive adults can help children and adolescents to develop the coping skills to deal with adversity. In this way, what might have developed into a toxic or chronic stress experience becomes one of 'positive' or 'tolerable' stress. In fact, it is the long-term study of young people who demonstrate resilience in the face of considerable adversity that has led to this insight. This subset of children demonstrate life outcomes that are “remarkably positive” when others from similar backgrounds are affected by impairments in learning, behaviour, physical health and mental health.

Through the investigation of these resilient children we now know that there is no such thing as a 'resilience gene'. As the Harvard researchers concluded in their 2015 report on resilience:

"Despite the widespread belief that individual grit, extraordinary self-reliance, or some in-born, heroic strength of character can triumph over calamity, science now tells us that it is the reliable presence of at least one supportive relationship and multiple opportunities for developing effective coping skills that are essential building blocks for the capacity to do well in the face of significant adversity.

Even in the most challenging situations, children and adolescents thrive when surrounded by supportive, caring adults and deep, enriching learning experiences which incrementally expose them to 'positive stress', leading to a belief in their own ability to cope with and adapt to adversity — a valuable life skill that they will continue to call on for the rest of their lives."

Enjoy the semester break, and let us pray that Semester 2 is much more settled than the last few months.

Pax et bonum

Kerrie Tuite

(tuitk@staff.mta.qld.edu.au)