Connecting to Learning in the DP: Chemistry

It’s all about bonding and relationships

Chemistry is a study that has often been described as “the central Science”. This appellation, popularised in the second half of the 20th Century, describes Chemistry’s position as the branch of Physics that deals with the tangible universe. More narrowly, Chemistry deals with the ideas of matter and change. All properties of matter and change that we observe as humans can be linked to the arrangements of electrons and atoms in the substances we encounter, obeying relatively simple rules.

The Chemistry Diploma Programme involves studying many topics, some abstract, some immediately testable. Students begin the course in familiar territory, exploring the atomic model and identifying subatomic particles. Quite rapidly, though, students move from simple factual understanding of atomic structure to more complex explanations of how electrons are configured in atoms, leading to a deep understanding of emergent properties and an ability to make predictions.

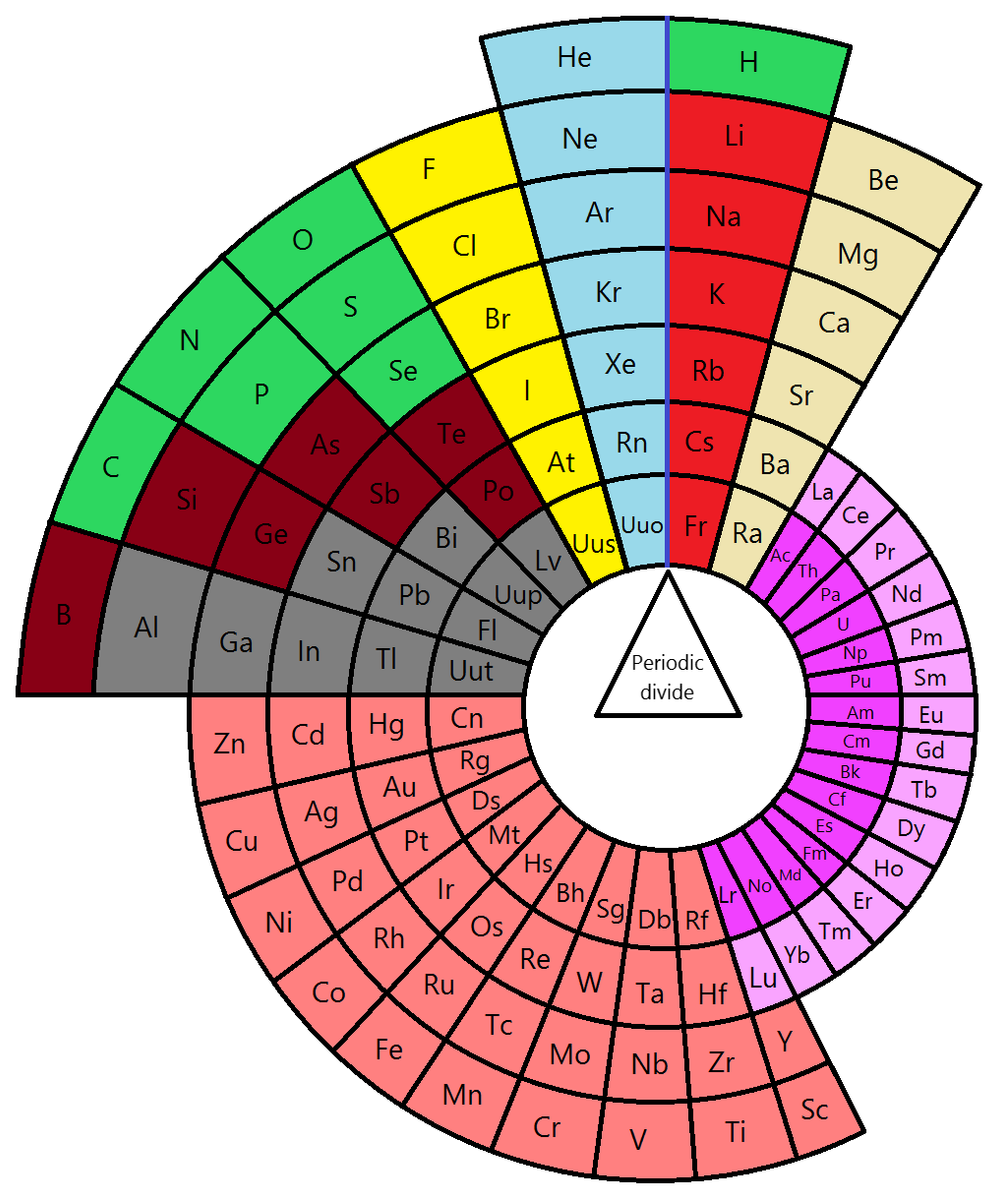

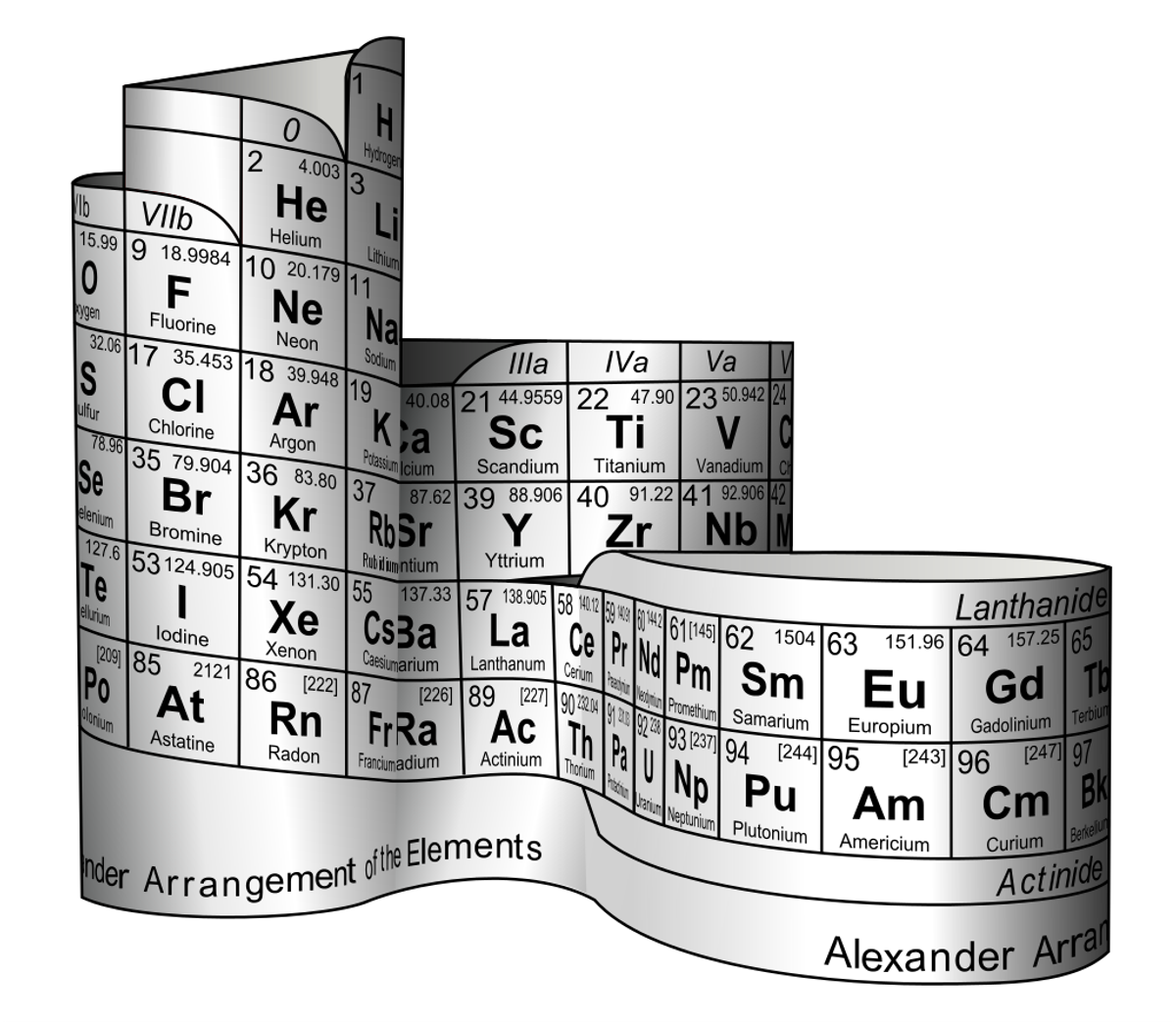

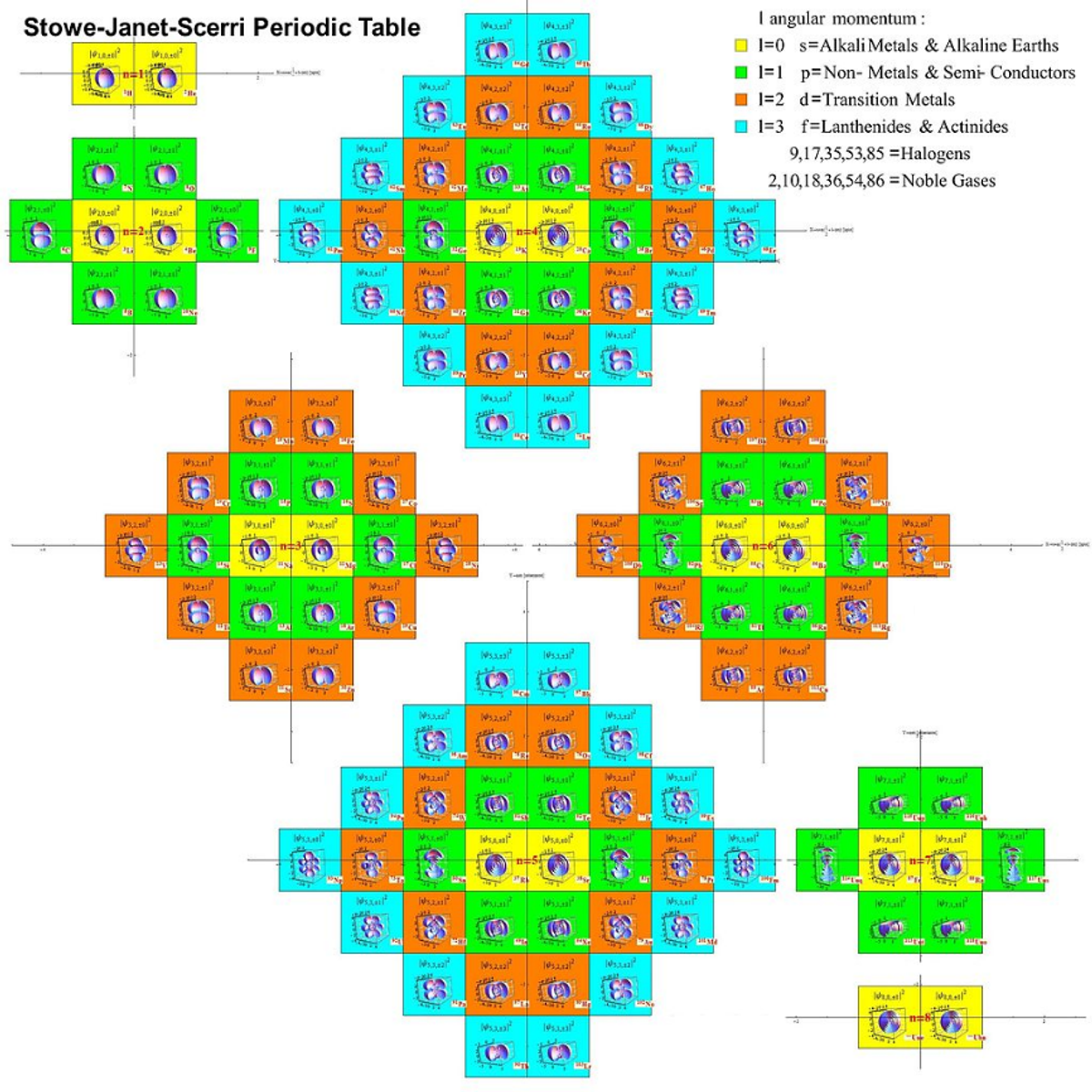

Many atomic properties vary in consistent ways with shifting numbers of protons or electrons. This fact was first noticed by scientists over 200 years ago, resulting in the discovery of the Periodic Table. While the familiar, rectilinear table that adorns almost every Science classroom and many an aspiring young scientist’s wall can be said to have been first drawn up by Russian father of Chemistry Dmitri Mendeleev in 1869, the “true Periodic Table” is better thought of as a multidimensional intangible concept, fundamental to the working of the universe.

As the students progress along their journey from atoms to periodicity, they lay a groundwork of understanding that allows them to explain bonding between atoms and particles, predicting how matter will look, feel and react under different circumstances. By halfway through the first year of the programme, it is possible to elaborate quite specifically on the literal difference between chalk and cheese! Other questions that can be answered include, “Why is graphite sometimes called greylead?” and “Why do helium balloons float, but lead balloons sink?”.

It is important for students of Chemistry to always keep the fundamental rules in mind and consider how the relationships between different concepts lead to incremental understanding.

The solution to all your problems

As mentioned in this article, Chemistry is a subset of Physics. As such, DP Chemistry is an inherently numerical study. Students are often taken by surprise when moving from Middle Years Science to Senior Chemistry that numbers are not just used for balancing reaction equations, but are used to measure, quantify, explain, predict and understand. It is extremely important that students entering Chemistry are adequately prepared for this and open to freely engaging with numerical problem solving.

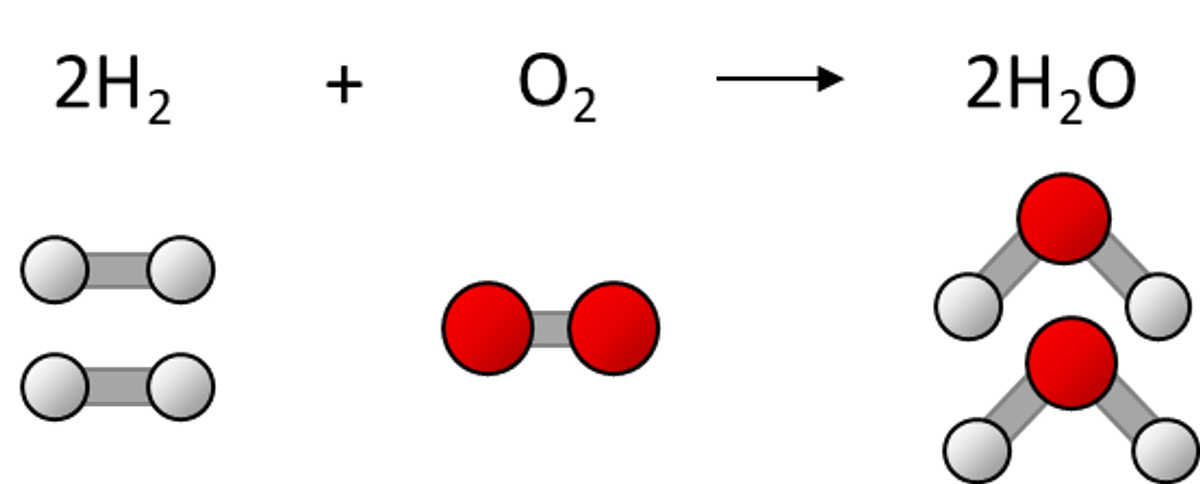

The general term used to quantify matter in Chemistry is stoichiometry. This applies to two distinct but related ideas. The first is the balancing of numbers of atoms in reaction equations. This type of stoichiometry is explored throughout Middle Years and Senior Chemistry. It is largely a balancing act and students often find treating the molecules as “packets” and the atoms as “items” helps. For example, two water molecules (two packets, each with two hydrogen and one oxygen atom, 6 atoms) contains the same number of atoms as two hydrogen molecules (two packets of two hydrogen atoms, 4 atoms) and one oxygen molecule (one packet of two oxygen atoms, 2 atoms).

The second meaning of stoichiometry is the calculations used to quantify matter. The first quantity students cover is “the mole”, a number that allows chemists to relate the number of atoms present in a sample to their mass. Individual atoms are exceedingly small; it takes 602 million, million, billion atoms of hydrogen to make up 1 gram. This is Avogadro’s constant.

After the mole, students learn about limiting reagents, solution concentration and gas laws. This allows them to accurately predict the outcome of reactions and interpret results to explain what happened on the atomic level. For example, by the end of the first year a Chemistry student will be able to determine the volume of gas released when a volume of acid is added to a mass of a metal salt. Remembering the bonding concepts covered in the first half of year, they will be able to propose tests to determine the identity of the gas. This might allow them to decide if they have simply added vinegar to bicarb of soda or, more dangerously, added hydrochloric acid to sodium sulfide.

The mathematical approach to Chemistry is empowering. It allows chemists to transfer “theoretical” understandings of nature to answer genuine and important questions and solve world-changing problems.

Simon Gooding

teacher of DP Chemistry