Cultural Stories

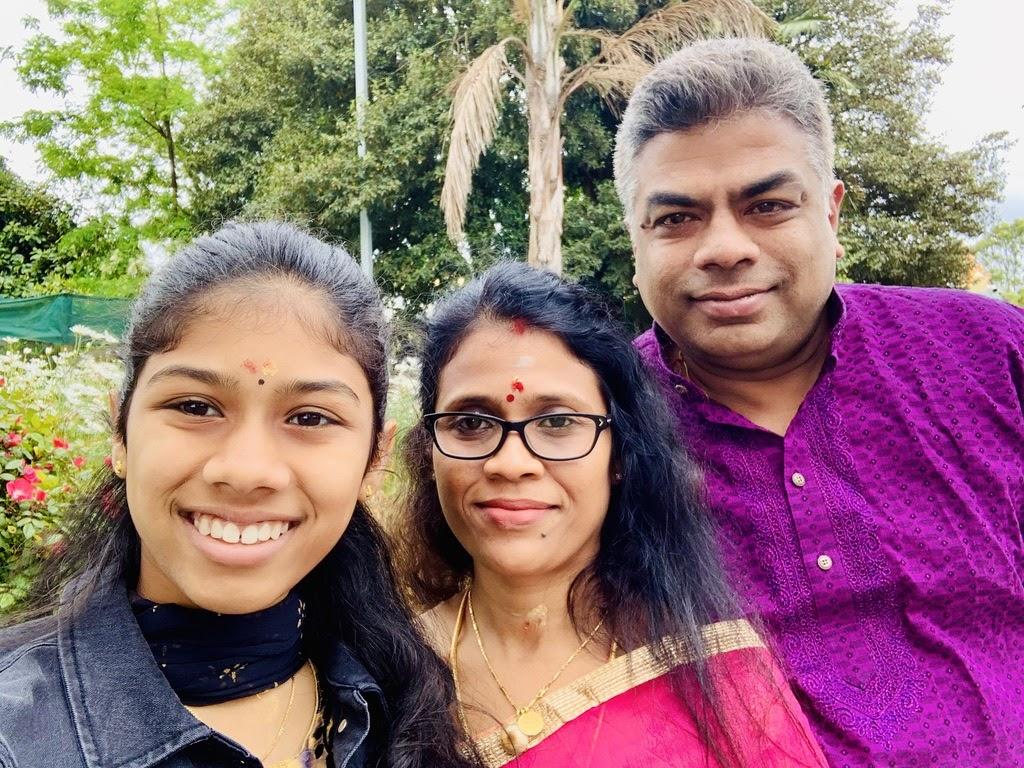

Meruna Mayooran

Hi, my name is Meruna Mayooran and I am in Year 7 from St. Nea. Today I will be talking about my family’s Cultural Story.

My family and I come from Sri Lanka and are hindu. My parents and grandparents were born in Sri Lanka however I was born in Australia. Some things my family and I do are going to the temple every Saturday as well as special days. This hasn’t been possible this year (because of the Coronavirus Pandemic). However, the sessions are live streamed online meaning we can still pray and watch what's happening in the comfort of our own home.

A celebration we celebrate is called Diwali (also known as the festival of lights). Diwali is celebrated near the end of October every year. During the day, we receive new clothes and then go to the temple to pray. Once we finish that go home and get ready for the evening. During the evening, my family usually meets up with our extended family, light lamps and sparklers and have dinner together. I really enjoy Diwali since I get to meet my cousins who I don't usually see regularly.

There are many different types of cultural clothing we wear. The main one i wear is the skirt and blouse. The skirt and blouse usually come together and they can consist of many different colours. With the skirt and blouse, people usually wear bangles, necklaces, fancy earrings, ect. We usually wear cultural clothing for any cultural ceremonies or simply when going to the temple to pray. Another time I wear cultural clothes is when I do Srilankan/ Indian classical dance, bharatanatyam.

I really enjoy visiting Sri Lanka. We try to go every three year however, we couldn't go this year. Usually we stay at my grandparents house (from my mum’s side). We go to visit our family living there and to go to the temples that are in Sri Lanka. Some other places we visit however are fishing ponds, shopping centres, famous landmarks, etc.

By Meruna Mayooran- St Nea

Tanvir Hothi

Namdhari Educational Organisation

Last year I handed in a video (of myself singing) to the world Namdhari educational organisation in which the youth from all over the world were taking part. You had to be 10-16 (Junior) or 16-25 (senior) to take part in this competition. The competition’s main point was to stay connected to your culture even during the lockdown. It also encouraged teens to get off their devices and practise. The competition happens typically in Sri Bhani Shaib (India), but due to Covid-19, they held it online, so everyone around the world could join. The video had to be five- six minutes long of you singing in Punjabi. You also had to wear traditional Namdhari white clothes during the video to represent your respect for the culture.

I played the harmonium (a keyboard instrument in which an air-driven produces the notes through metal reeds). I sang a Raag (melodic mode in Indian classical music). The Raag’s name is Raag Yaman ( Raga Yaman expresses the ultimate humility). Prayer and love are complementary and expressed through the rendition of the Raag, just like the inseparable connection between the moon and moonbeam, or between fish and water.

After weeks of waiting for the results for this competition, my mum found out I was the winner of the competition, tied with another person. I was so happy, proud and surprised, just like the rest of the family. I then told my other family members in India, and they were so pleased; my grandma started crying, happy tears, because I came first. I would like to thank everyone, especially my parents, for always encouraging me a lot to practise every day and I would like to thank my music teacher (Avtar Kaur) for always giving me the best

Sienna Pasitchnyj

Vareniki - the most amazing Ukrainian food ever, two Christmases every year and huge family gatherings are just a few of the things that I think of when asked about my family. They’re the things I’ve always had, and always loved, but they’re also things that I have because of my cultural background, and I’m extremely grateful for that.

I’m a third-generation migrant, with three out of four of my grandparents being migrants from different European countries. My dad’s parents are both migrants from Kyiv, Ukraine, who escaped during WW2 and came to Australia by boat, where they met. My Mum’s father was also a migrant, but from Sicily, Italy. Something that has always stuck with me is my grandpa’s story about coming to Australia by boat. His famous saying ‘fifty days, and fifty nights’ is something I will always remember and cherish.

When I look at my daily life carefully, I find that it reflects my cultural background. The food we eat - lots of pasta, from my Mum’s Italian side, and Varaneki, from my Dad’s Ukrainian side. Hearing Ukrainian being spoken at my Dad’s parent’s house and some Italian at my Mum’s parent’s house. Even all the food we grow at home reflects my Mum’s Italian heritage, as her father used to grow all his food in Italy, and then in Australia, this is something we’ve carried on.

My cultural background has also had a big impact on my religion. While I have grown up Catholic, going to both a catholic primary and secondary school, I do participate in the traditions and practices of the Ukrainian Orthodox church. Weddings and funerals are very different from catholic ones, both in the churches we go to and the practices. My parents got married in a traditional Ukrainian Orthodox church. This photo was taken during the crowning ceremony, where the couple has crowns placed on their head, signifying that they are now married, and the man has new responsibilities.

Alicia Hereford

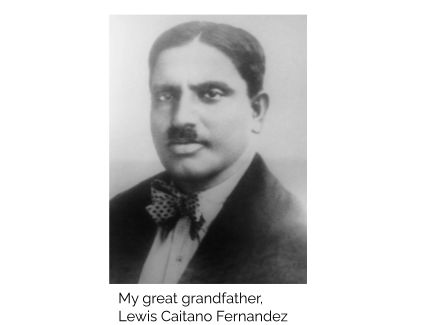

My Anglo-Indian Heritage

I am often asked why I have an Anglicised name when my appearance is Indian and I am sometimes teased by my friends for being “whitewashed”, as I only speak and understand English, while they are multilingual and well versed in their native language. All of this can be accounted for by one simple explanation: I am Anglo-Indian. However, often when I tell people this they drop the prefix and focus only on the latter, not understanding just how much history lies behind the term. An “Anglo-Indian” refers to a person with mixed European-Indian heritage. We are not quite Indians, though we are heavily culturally tied to the country. We are not quite British or Portuguese, but our family tree is often rooted in Europe.

In the 18th century, employees of the British East India Company were strongly encouraged to “plant roots” by marrying native Indian women, even being paid a sum for every child conceived from these marriages. When the British finally departed in 1947, they abandoned a mixed-race sub-population of about 300,000. Although lesser known, the Portuguese ruled certain parts of India from 1505 to 1961, and also produced offspring of mixed heritage who fell under the Anglo-Indian label.

Under this label, people felt betrayed by the British and Portuguese and were ostracised by the rest of the population, stigmatised by most Indians as “Kutcha-Butcha” (half-baked bread). They stuck out like sore thumbs: speaking English as their first (and usually only) language, donning Western clothing, having Anglicised names and being raised as Christians. Only the slight accent and darker complexion betrayed their origins. As a result of this alienation, hoards of the Anglo-Indian population began migrating away from India, dispersing amongst Commonwealth countries including Canada, the UK, New Zealand and, of course, Australia.

My last name, Hereford, is a dead giveaway of my British heritage on my dad’s side, whose ancestors originated in Herefordshire, a county in the West Midlands of England. On the flip side, my mum’s family can be traced back to Portugal, as my great-grandfather was Portuguese. While in India, my parents, like most Anglo-Indians, felt more Anglo than Indian and desired to leave their homeland in search of a more opportunistic life. However, now that they are in Australia, they are reminiscent of their life in India and cling onto their Indian heritage and culture.

This is true not just for my family, but for thousands who have migrated to Australia from different parts of the world. Identifying and keeping these many cultures alive is important not just for individuals, but for Australia as a nation. Each and every Australian has a unique and special cultural story, which serve as intricate puzzle pieces that make Australia one of the most culturally and linguistically diverse nations in the world with a vibrant and multicultural society.

Emerald Nguyen

When it comes to Vietnamese culture, the first things that come to mind are the celebrations,the language, the traditional clothing and the food but, most importantly, it's the people andthe stories of each and every individual.

My family story begins with my parents. In 1986, my dad made the decision to leave Vietnam and seek refuge in Australia. There was a political crisis at the time, resulting in a great divide between the North and South of Vietnam. Peace had left the country and Vietnam nolonger promised a future, for better or for worse, it marked a new beginning. My dad,accompanied by his father and five other cousins, made their journey on a small, crowded fishing boat across the vast and wide ocean. Together, they faced stormy seas, with very little food and water, as well as many restless nights with constant fear of being invaded by pirates. Fortunately, a week later my dad and his family safely arrived at a refugee camp on Galang Island, Indonesia, where he waited six months before settling in Melbourne,Australia. Like the roots of a tree that did not cease, my dad remained strong and regarded his difficulties as an opportunity to thrive and lay the foundations of his next big chapter. He learnt to adapt to a new environment, worked to provide for his family, met many new people and learnt an entirely different language. I truly hold a lot of respect for his hope, optimism, courage and perseverance.

As well, religion has played a significant role in my life and it has guided my parents, people of the Buddhist faith, to uphold a principle of peace and goodwill. From a very young age, my parents instilled in my brother and I, the importance of gratitude, kindness and hospitality to those most in need. I’ll never forget the first time my parents encouraged my involvement to help purchase, organise and deliver treats and goodies to a small school of students. A small act of kindness can truly go a long way, to see their joyful expressions was truly a gift and a reminder of my own blessings. You know it’s incredible, there’s always so much more to discover about our own culture and traditions, so I encourage everyone to reach out and engage in a conversation with your own parents!

Jessica Vu

My family originates from Vietnam and China, however I identify more as Vietnamese due to my upbringing. My family is from both the Northern and Southern regions of Vietnam, though I’ve only been back to visit my family from the North. When I went there in 2014 I had the pleasure of meeting my grandfather for the first and last time. My grandfather was born in 1934 and he went by the name Nguyen Van Hue. He lived in rural Vietnam, thriving in the heat of the countryside before he turned 15 where he moved to the city to find a job. He worked countless jobs before finally signing up for war when he was 18. He ended up working as a driver during the Vietnam war from the 1950s to the 1970s. He transported artillery and weapons to and from the battlefield. When the war ended in 1975 he came back safe and sound, and ended up becoming the leader of his village community and continued his job as a driver, transporting people from region to region. As a leader, he worked on helping those less fortunate, looking out for sick and elderly people. He organised funerals and weddings within the community and overall was admired by the close-knit village. When I met him for the first time I could tell he was extremely respected by the people around him, as a picture of him was hung up in the community centre. He was extremely warm and a genuinely wonderful person, I could tell this by not only what he showed but his actions in the past - he had taken in my mother who isn’t his natural-born daughter and raised her up as family. And, thanks to him, I’m able to have the mother I have now, someone who is loving and compassionate. He passed away in 2015 at the age of 81 and his funeral was held in his village. I was unable to attend but my mother flew back for the ceremony. Though my grandfather may not have fought in the frontlines of the Vietnam war, he played a huge role in both his community and my life, without him my mother wouldn’t be the same person she is now and I’m forever grateful for that.

Grace Wilson

My family is from South Sudan which is a country in east Africa. South Sudan is currently the newest country as we separated from North Sudan in 2011. The people of South Sudan are split into sixty different tribes and my parents are from two different tribes. My Mum is from a tribe called Zande and my Dad is from a tribe called Pojulu. My mums parents were also from two different tribes but she identifies with her fathers tribe as well as my siblings and I, even though both our parents are from two different tribes, we would be identified under our fathers tribe. At home we speak English and Arabic and my parents can speak the mother tongue languages of their own tribes as each tribe has its own language, but Arabic and English is the central language for the majority of South Sudanese and Sudanese people. I was born in Egypt and have never been there but my parents talk about how great it is every single day. Most of South Sudanese people are Christians and Sudanese people are muslims, my Mum is Catholic and my Dad is Christian but my mum went to a muslim school for a while when she was younger so she knows all their practices. My parents as well as many other immigrant parents, went through a lot of struggle and hardships to get us where we are now from going through the second Sudanese civil war which went for 23 years to having to leave their families behind. I still have family that move around living in South Sudan, Kenya and Uganda that I talk to all the time. Here in Australia, we celebrate tribe days and the day of our referendum annually where we dress up and join together as a community. From the food I eat, the language I speak, my hair and my appearance, I am proud to say that I belong to a culture and will continue to pass this down.

Zi-Yan Lean

My Background

My great grandparents were born in China and migrated to Malaysia due to the ongoing war that was happening at the time. My grandparents and parents were both born in Malaysia, therefore, inheriting a Chinese-Malaysian culture. My father adventured out to Australia to seek better job opportunities which took a lot of courage as someone who didn’t understand any English and didn’t know anyone in Australia. He worked day and night at any place that would welcome him and eventually was able to bring my mother over. My parents lived in Warrnambool for a few years before coming down to Melbourne. My parents are the reason why my siblings and I were able to grow up in an amazing place and get given many different opportunities that they didn’t have. My family has followed more western traditions instead of Chinese-Malaysian traditions because we were born in Australia and do not have many relatives around us. However, one tradition we still follow is having 长寿面, “Chang Shou Mian” and eggs on birthdays. “Chang Shou Mian” also known as Longevity Noodle, represents having a long life. The eggs symbolise new life and are eaten to signify another year passing and a new year coming.

Cheska Yalung

My family came from the Philippines. My entire family was born there, including my two siblings and I, but moved to Australia in February 2012.

The majority of us Filipinos are Catholic. Back in the Philippines, we took Holy Week very seriously. For us, it was a time for atonement. For the entire week, there would be people in the streets marching down literally recreating the suffering that Jesus went through prior to being crucified. I was so scared of seeing them with their bloodied backs and whips and I would hide every time they would come down the street. The Holy Week would end with people actually being crucified. Though it is a normal and anticipated spectacle, I was not at all excited to watch.

By September, the countdown begins for Christmas and Christmas decorations are already up. We love Christmas and love large celebrations. I can remember looking at the news as a child, and there would be a countdown at the end of the news, that there are 136 days till Christmas and can remember the excitement. During the month of Christmas, I'd gather with a group of friends from the same street and we'd go door to door singing Christmas carols and get pennies or two. I doubt we had much talent, but the fact is we were cute little kids so we still got money.

Christmas morning and we'd be dressed in our best red clothes and we'd come to visit our relatives. We'd take their hand and press our foreheads on their hand as a sign of respect. They would then give us money, the crisp newly printed ones. At the end of the Christmas day, we'd have our pockets full of money. We'd have large gatherings and celebrations filled with food, family and fun. As a child, December was a magical month. There would be beautiful lanterns (we call "parol") in the streets. Everywhere you see shows signs of Christmas, in our homes, out in the streets, in church, in the shopping centres, you name it, it's everywhere. The atmosphere during December in anticipation of Christmas is simply exhilarating.

Though in eight years of living in Australia, we have adapted to the traditions and culture, but there are aspects that can't ever be replaced. The excitement, the vibe and the atmosphere of the December month in Australia can't ever amount to Christmas time back in the Philippines with our families where it was truly, truly magical.