The Green Page:

Haere mai ngā kaitaiao tangata whenua. Welcome, fellow citizen scientists. New Zealand’s largest and longest-running citizen science project is about to begin, and we are thrilled to invite everybirdy to join us and make our birds count.

The New Zealand Garden Bird Survey has been running for 18 years, with a rich story emerging from the trends in garden birds across the motu.

The challenge now is to continue and gather as much information as possible. These ongoing data serve to confirm if the trends we see are just a blip or something that needs further investigation. It’s essential to keep counting, as the more people who participate, the richer the story that will emerge and the deeper our understanding will become of local garden bird trends.

Get involved. Grab your whānau, friends, and neighbours – it’s time to head into the garden (or local park) for one hour on any day between sunrise on Saturday, 28 June, and sunset on Sunday, 6 July, and count all the birds you see or hear.

Yes, it does mean you might have to put on the winter woollies, or if it’s raining, sit inside and look out the window, but always remember you might just be one person, but you can make a difference.

Garden birds are important to study because they serve as an indicator of the environmental health in which we live. Every sighting matters. The information gathered from this survey helps inform conservation decisions and inform further research.

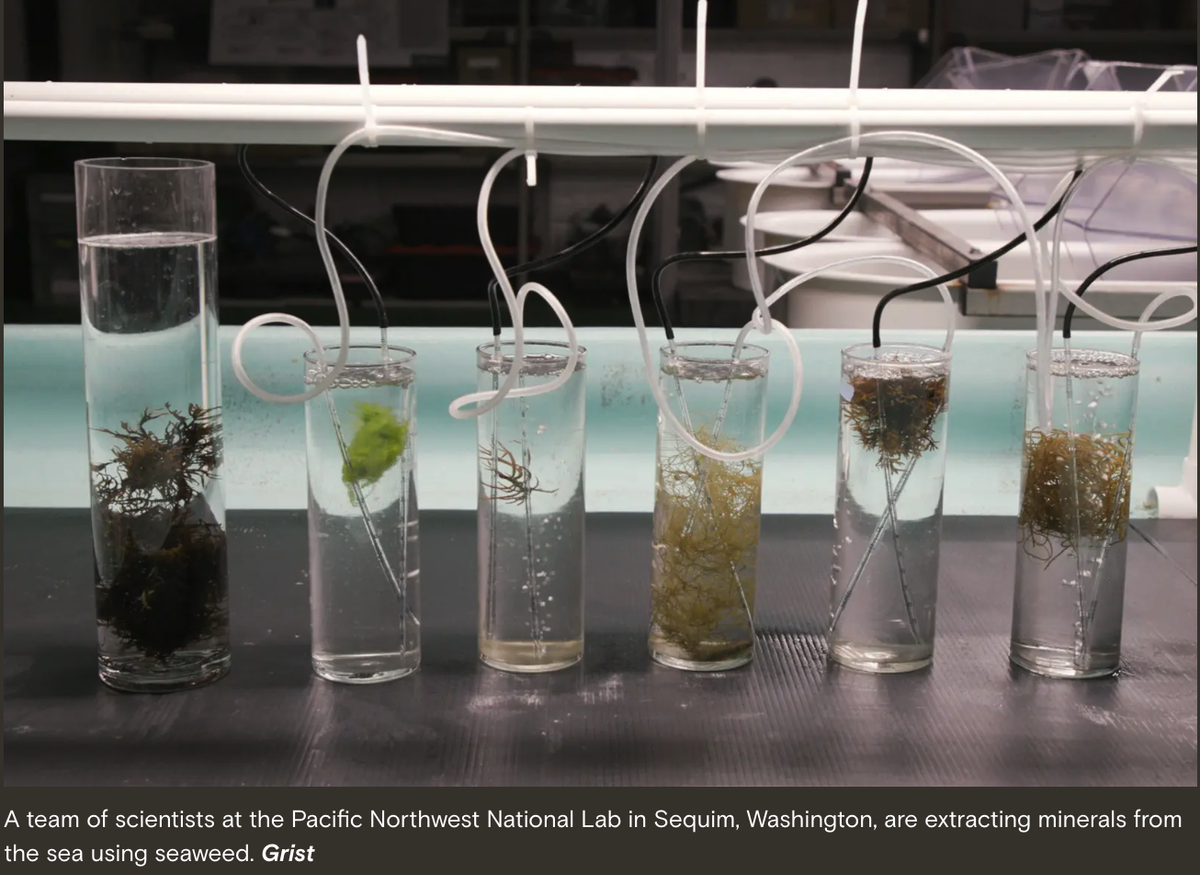

The Weirdest Ways Scientists Are Mining For Critical Minerals, From Water To Weeds

Not all critical minerals need to come from digging up the earth.

Mining outer space

A big problem with finding the metals needed to power the energy transition is that the purest ores available in Earth’s crust have long been used up. The more we mine, the more we’re chasing lower-quality, harder-to-access reserves.

To bypass the increasing environmental cost associated with churning up our world to access the riches stored within, starry-eyed entrepreneurs and engineers have turned their gaze to the heavens. They’re hoping that primordial rocks left over from the formation of the solar system, drifting between the planets untouched for eons, could provide all the metals that humanity might need for centuries to come.

“Asteroid mining as a whole is the only solution that anybody has devised that is a holistic approach to cleaning up mining,” said Matt Gialich, founder and CEO of the California-based company AstroForge.

AstroForge and a small handful of competitors are proposing different ways to one day extract materials from an asteroid and return them to Earth. However, the nascent industry has a long path ahead: to date, only three missions — none of which were undertaken by the private sector — have successfully visited asteroids near Earth and returned home with samples.

But in late February, AstroForge’s Odin spacecraft hitched a ride on a SpaceX Falcon 9 alongside other vehicles destined for the moon. If successful, Odin would be the first commercial deep-space mission in history, likely traversing hundreds of millions of miles before darting by its target asteroid to photograph it and confirm its metallic composition. (After launch, however, Odin appeared to be in a slow, uncontrolled tumble on its way to deep space, and Gialich and his team struggled to communicate with the spacecraft. As it drifts further into deep space, their chances of success diminish.)

Metallic asteroids are prime targets for off-world mining because of the high concentrations of valuable elements, particularly nickel, cobalt, iron, and platinum-group metals, they may contain. (Until a spacecraft successfully visits one of these bodies, we really only have estimates based on meteorites believed to have originated from similar asteroids.) At first, the space miners would focus on platinum and related metals because they are some of the most valuable on Earth: A ton of platinum costs over $30 million, whereas a ton of nickel sells for around $20,000. Gialich estimates that Astroforge’s future mining missions could return one ton of platinum each.

Eventually, once they have established their profitability and can shift to collecting the abundant iron, nickel, and cobalt that asteroids also contain, Gialich and others hope that a thriving asteroid mining industry could lead to a moratorium on mining on Earth.

“I think if we are successful,” Gialich said, “this makes precious metal mining on the planet illegal.”

Before that happens, there are several kinks to be worked out. Currently, under the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, no country can claim territorial rights to land on another celestial body, such as the moon, an asteroid, or Mars. However, emerging national laws have given companies and countries the license to extract materials and claim a legal right to anything they can physically take for themselves.

More importantly, perhaps, no one yet knows the best way to extract these metals. Some have suggested using special chemicals to dissolve the materials and filter out the desirable metals. Others have discussed using magnetic rakes to comb through the pulverised dust coating the asteroids, pulling out the rocks and granules that contain platinum group metals. One recent paper even proposed using nuclear thermal rockets to melt the asteroids, then collecting the molten materials in crucibles and allowing evaporation to separate the metals.

Even if a workable method is devised and the raw cost-revenue calculations work out to make it a profitable industry, space mining raises deeper questions. The launches required to propel mining vessels into deep space would consume tremendous amounts of fuel and further exacerbate the space industry’s growing problems of polluting the upper atmosphere and harming biodiversity. The mining itself, without proper regulations, may even create new streams of meteors that could endanger satellites providing crucial services to the people of Earth.

Despite its challenges, many in and around the field argue that their efforts will not only make the energy transition more sustainable but also be a necessary step for humanity to evolve beyond its earthly cradle. But is it worth expanding into the final frontier if we haven’t yet learned to tread lightly?