Teaching & Learning Page:

Web Pages:

Techie Tips:

Sketches:

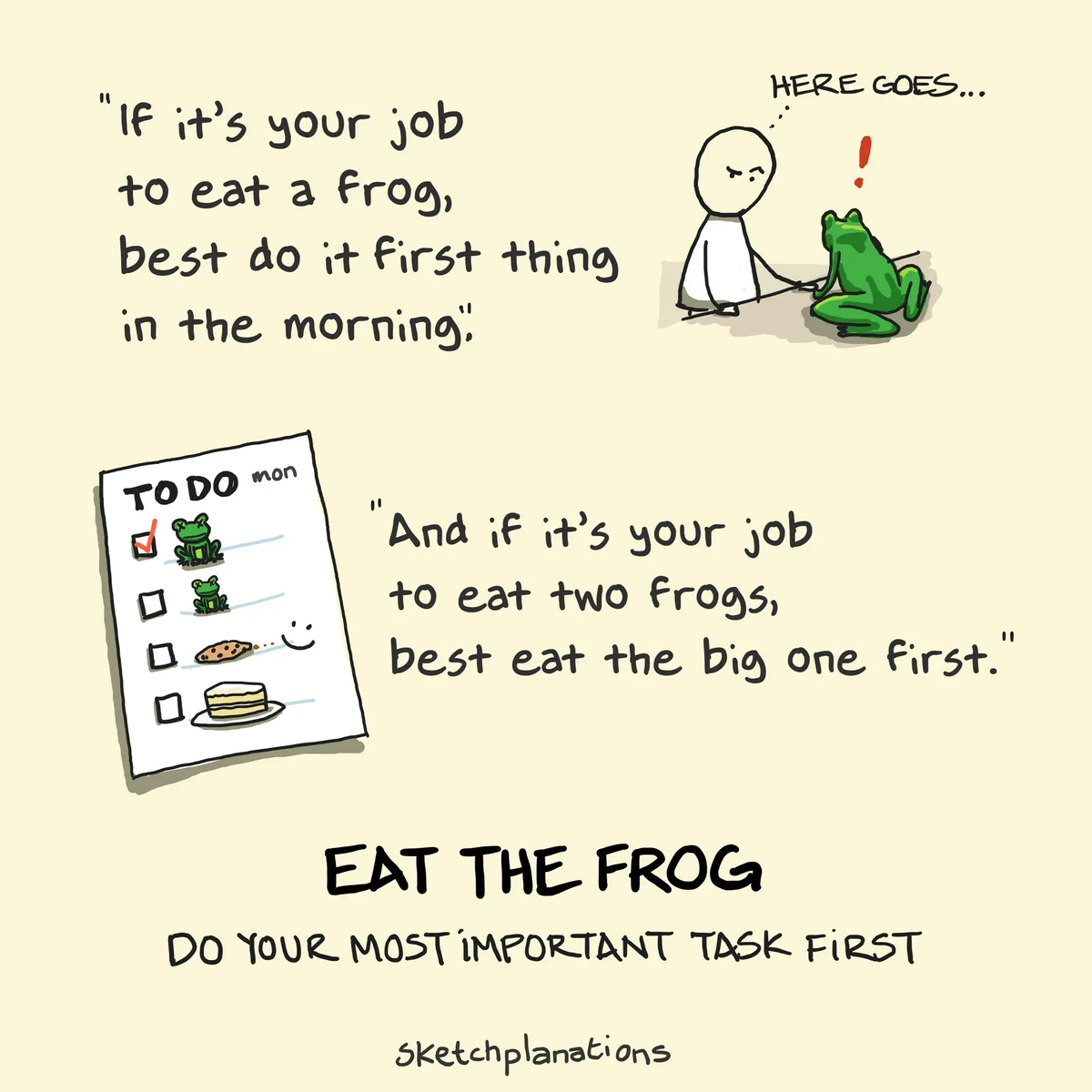

Eat the Frog is a memorable, if rather gross, metaphor that means choosing the most important thing you must do today and doing that first.

It derives from a variant of a quote that Mark Twain never said, "If it's your job to eat a frog, it's best to do it first thing in the morning. And if it's your job to eat two frogs, it's best to eat the biggest one first."— Not Mark Twain.

Another way to think about it is that if you first Eat the Frog, everything else will be easier for the rest of the day. And won't that feel nice?

The Eat the Frog time management technique was popularised in Brian Tracy's productivity book Eat That Frog! Get More of the Important Things Done - Today!

Many tools in Tracy's book are based on the general premise that there will always be more to do than you can do. So, find the things that will have the most impact and do those first. The others will drift on by.

Why is Eat the Frog helpful?

I once saw someone ask for advice on how to get motivated to clean the house. One person answered: "Write a book."

Sometimes, our most significant and impactful goals are those on which we so readily procrastinate. Often, these will be in the important, not urgent, bucket.

The Eat the Frog approach helps if:

You are prone to procrastination 🙋You have a lot of things that need to be done or that you want to do. You work well in the morning. One of the nice things about eating the frog first thing is that getting it done feels really good. It helps build momentum for the rest of the day with a nice endorphin rush of ticking off something significant.

Decide on your Most Important Task (MIT) to tackle, ideally the night before. If it's too big and you can't finish it in one sitting, divide it into manageable chunks. Then start on the first chunk and leave everything else.

And sometimes, the hardest thing to do is to start. So consider doing just 5 minutes. Once you've started, very often, keeping going becomes easy.

Challenges when Eating the Frog

Questions that come up regularly in Tracy's book "Eat That Frog ", including for the Eating the Frog principle, are variations of:

What is the most important thing you could be doing?

What is the highest-value activity?

What activity will have the most impact?

If you weren't already doing this, would you start doing this?

What skills will take you furthest in your career?

What are you able to do best that others can't?

It all looks pretty straightforward when I read questions like these. However, I have found that answering them is usually much more challenging.

Our goals are often interrelated. For example, earning more may require you to first enhance your skills. Getting clear on what your most important goals are first is a prerequisite, and it's not always straightforward.

Then, what activities are the most important or will have the most impact can be unclear. And sometimes, small actions, such as an unexpected event or connection, may have outsize benefits. Or neglecting a seemingly minor task could lead to losing a significant client. But does it still make sense to tackle the most important task first thing in the morning?

Yes.

Don't Drag it Out.

Like a child leaving a brussel sprout at the side of the plate to get cold while they eat the roast, it's easy to leave our most impactful and daunting tasks until after the easier stuff is done. But it doesn't usually help to wait.

As the saying goes, if you have to eat a live frog, it doesn't pay to look at it for long.

Every creation is a mirror, reflecting something of its creator. If you and I were to paint the same subject, your painting would reflect some of you, and mine would reflect some of me. If we both write stories, each one will carry something of ourselves—our personality, our experiences.

The writer is in the writing. The artist is in the art. The musician's in the music.

Take writing as an example. If we're writing authentically, we can't help but share a bit of ourselves in our work. Our past experiences affect what we notice. Our timidity or confidence is reflected in the tone and style. Our education in the choice of words. Our kindness and patience, or cynicism and frustration, are revealed to the reader. And the choice of what you write or paint reflects you.

Not if we're trying too hard. Not if we're writing to sound like a writer or if we're adopting a "literary" style because we think that's how it should be done. And not if we focus more on pleasing a search engine or ticking off marketing goals than connecting with readers. However, if we write honestly and directly, the writer's voice shines through.

The Third Dimension

This phrasing struck me while reading Brenda Ueland's book, If You Want to Write. She calls the writer the Third Dimension. I believe she means that when you read a book, there are the characters, the reader, and also, inescapably, the writer's personality. She writes that readers can tell when writing isn't authentic, when it's not really you, but instead, a performance to meet someone else's expectations of how one should write, or perhaps a creation of an AI's sycophantic personality.

The presence of the writer in the writing, or the artist in the art, leads Ueland to say, "…I have come to think the only way to become a better writer is to become a better person."

I believe this principle also holds true across other creative disciplines, though I thought "the cook is in the cooking" didn't quite have the same ring. Still, it holds a ring of truth if I consider a musician and their music, an entrepreneur and their business, a podcaster and their podcast and others.

It's hard to write this without wondering what I'm sharing about myself (and what gets scrubbed out and cleansed by Grammarly proofreading). In Sketchplanations as a project, I've come to realise that sooner or later, everything of value I know will be there.

Article:

Math Makes Life Beautiful.

Math has long been the language of science, engineering, and finance, but can math help you feel calm on a turbulent flight? Get a date? Make better decisions? Here are some heroic ways math appears in our everyday lives.

Sounds intellectually sophisticated, doesn’t it? Other than sounding really smart at after-work cocktails, what could be the benefit of understanding where math and physics permeate your life?

Well, what if I told you that math and physics can help you make better decisions by aligning with how the world works? What if I told you that math can help you get a date? Help you solve problems? What if I told you that knowing the basics of math and physics can help make you less afraid and confused? And, perhaps most important, they can help make life more beautiful. Seriously.

If you’ve ever been on a plane when turbulence has hit, you know how unnerving that can be. Most people get freaked out by it, and no matter how much we fly, most of us have a turbulence threshold. When the sides of the plane are shaking, noisily holding themselves together, and the people beside us are white with fear, hands clenched on their armrests, even the calmest of us will ponder the wisdom of jetting 38,000 feet above the ground in a metal tube moving at 1,000 km an hour.

Considering that most planes don’t fall from the sky on account of turbulence isn’t that comforting in the moment. Aren’t there always exceptions to the rule? But what if you understood why, or could explain the physics involved to the freaked-out person beside you? That might help.

In Storm in a Teacup: The Physics of Everyday Life, Helen Czerski spends a chapter describing the gas laws. Covering subjects from the making of popcorn to the deep dives of sperm whales, her remarkably accessible prose describes how the movement of gas is fundamental to the functioning of nearly everything on Earth, including our lungs. She reveals air to be not the static, clear thing that we perceive when we bother to look, but rivers of molecules in constant collision, pushing and moving, giving us both storms and cloudless skies.

So when you appreciate air this way, as a continually flowing and changing collection of particles, turbulence is suddenly less scary. Planes are moving through a substance that is far from uniform. Of course, there are going to be pockets of more or less dense air molecules. Of course, they will have minor impacts on the plane as it moves through these slightly different pressure areas. Given that the movement of air can create hurricanes, it’s amazing that most flights are as smooth as they are.

You know what else is really scary? Approaching someone for a date or a job. Rejection sucks. It makes us feel awful, and therefore, the threat of it often stops us from taking risks. You know the scene. You’re out at a bar with some friends. A group of potential dates is across the way. Do you risk the cringingly icky feeling of rejection and approach the person you find most attractive, or do you just throw out a lot of eye contact and hope that person approaches you?

Most men go with the former, as difficult as it is. Women will often opt for the latter. We could discuss social conditioning, with the roles that our culture expects each of us to follow. But this post is about math and physics, which actually turn out to be a lot better in providing guidance to optimise our chances of success in the intimidating bar situation.

In The Mathematics of Love, Hannah Fry explains the Gale-Shapley matching algorithm, which essentially proves that “If you put yourself out there, start at the top of the list, and work your way down, you’ll always end up with the best possible person who’ll have you. If you sit around and wait for people to talk to you, you’ll end up with the least bad person who approaches you. Regardless of the type of relationship you’re after, it pays to take the initiative.”

The math may be complicated, but the principle isn’t. Your chances of ending up with what you want — say, the guy with the amazing smile or that lab director job in California — dramatically increase if you make the first move. Fry says, “Aim high, and aim frequently. The math says so.” Why argue with that?

Understanding more physics can also free us from the panic-inducing, heart-pounding fear that we are making the wrong decisions. Not because physics always points out the right decision, but because it can lead us away from this unproductive, subjective, binary thinking. How? By giving us the tools to ask better questions.

Consider this illuminating passage from Czerski:

We live in the middle of the timescales, and sometimes it’s hard to take the rest of time seriously. It’s not just the difference between now and then, it’s the vertigo you get when you think about what “now” actually is. It could be a millionth of a second, or a year. Your perspective is completely different when you’re looking at incredibly fast events or glacially slow ones. But the difference hasn’t got anything to do with how things are changing; it’s just a question of how long they take to get there. And where is “there”? It is equilibrium, a state of balance. Left to itself, nothing will ever shift from this final position because it has no reason to do so. At the end, there are no forces to move anything, because they’re all balanced. They physical world, all of it, only ever has one destination: equilibrium.

How can this change your decision-making process?

You might start to consider whether you are speeding up the goal of equilibrium (working with force) or trying to prevent equilibrium (working against force). One option isn’t necessarily worse than the other. But the second one is significantly more work.

Then you will understand how much effort will be required on your part. Love that house with the period Georgian windows? Great. But know that you will have to spend more money fighting to counteract the desire of the molecules on both sides of the window to achieve equilibrium in varying temperatures than you will if you go with the modern bungalow with the double-paned windows.

And finally, curiosity. Being curious about the world helps us find solutions to problems by bringing new knowledge to bear on old challenges. Math and physics are actually powerful tools for investigating the possibilities of what is out there.

Fry writes that “Mathematics is about abstracting away from reality, not replicating it. And it offers real value in the process. By allowing yourself to view the world from an abstract perspective, you create a language that is uniquely able to capture and describe the patterns and mechanisms that would otherwise remain hidden.”

Physics is very similar. Czerski says, “Seeing what makes the world tick changes your perspective. The world is a mosaic of physical patterns, and once you’re familiar with the basics, you start to see how those patterns fit together.”

Math and physics enhance your curiosity. These subjects allow us to dive into the unknown without being waylaid by charlatans or sidetracked by the impossible. They allow us to tackle the mysteries of life one at a time, opening up the possibilities of the universe.

As Czerski says, “Knowing about some basic bits of physics [and math!] turns the world into a toybox.” A toybox full of powerful and beautiful things.

Book Recommendation:

As a child, I watched a spectacular cartoon (directed by the great Chuck Jones)about a bear who woke up from hibernation to find his cave surrounded by a factory. The workers mistake the bear for a fellow employee, and refuse to believe him when he repeatedly insists that he is, in fact, a bear. It is an absurd, hilarious and powerful commentary on the societal pressure to conform, and how easily we can lose ourselves. I only recently discovered that the cartoon was based on a book by Tashlin, and I absolutely loved it, especially the ink illustrations.