YEAR 10 - HOLOCAUST MUSEUM

REFLECTIONS AND OVERVIEW from Teacher and Students

Mr Whittles overview (collaboration with Adam M in Year 10).

Earlier this term, our Year 10 students had the privilege of visiting the Melbourne Holocaust Museum, where they met with dedicated staff and two Holocaust survivors who generously shared their stories.

The first group of students met Peter Gaspar, who was born in 1937 in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia. As a young child during the Holocaust, Peter and his parents were forced to hide wherever they could; in cellars, cupboards, roof spaces, orchards, and even a snowy field hollowed out like a grave. Which was some of the most macabre imagery we heard from him and a burden he did not fully understand until adulthood. When Peter fell ill in 1944, his family had no choice but to surrender to the local police. He and his mother were deported to Theresienstadt, while his father was sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Remarkably, all three survived and were reunited after the war, later migrating to Melbourne in 1949. During his talk, Peter reflected on his survival and identity, reminding us that these traumatic events live with you across a lifetime but do not define you.

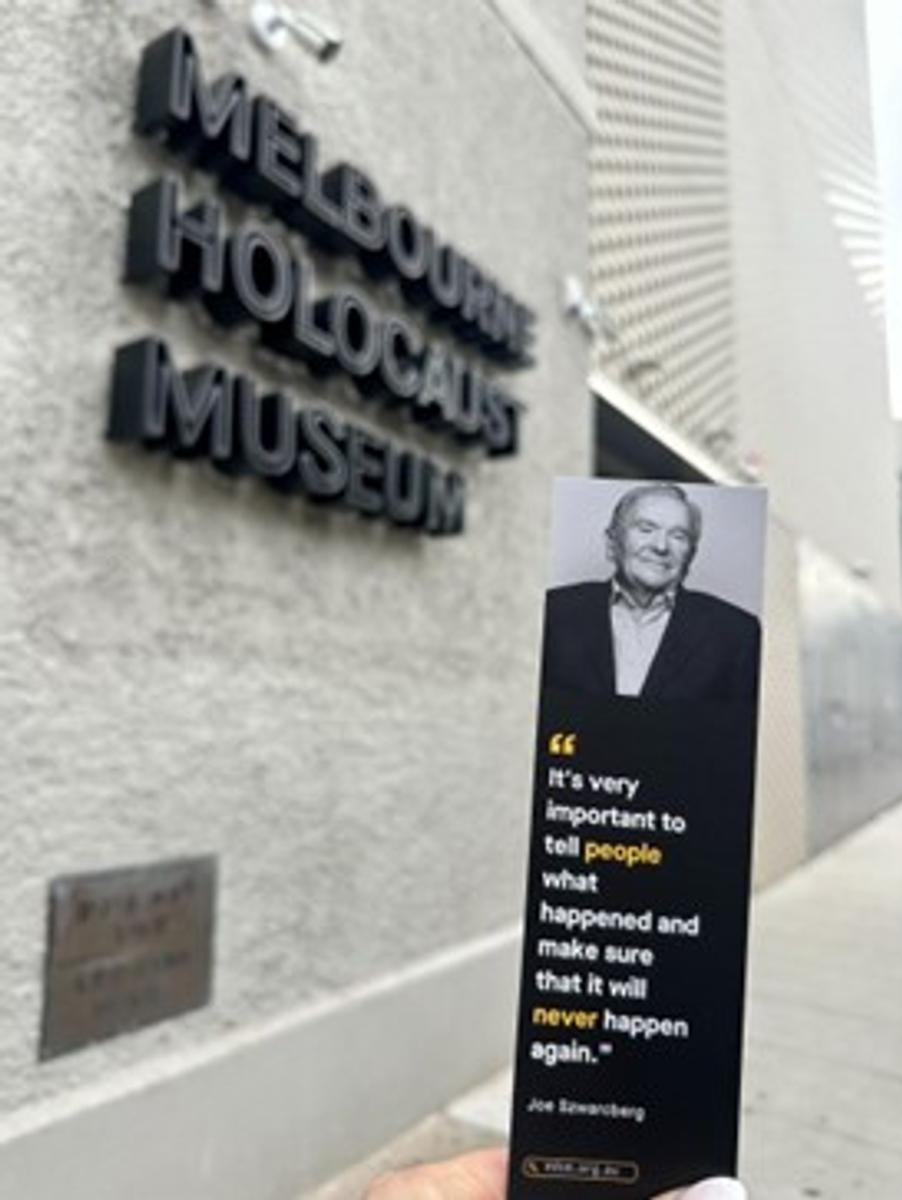

On the second day, students met Joe Szwarcberg, born in 1930 in Kozienice, Poland. At just nine years old, Joe and his family were forced into a ghetto after the German invasion. He risked his life sneaking out for food, but conditions claimed the life of his mother. He was later sent to a labour camp where he witnessed the murder of one of his brothers, before being deported to Buchenwald concentration camp in 1944. Liberated at age 15, Joe was reunited with his sisters, though his father and brothers did not survive.

For our students, hearing directly from survivors brought an irreplaceable perspective to their studies and lives. After our visit, we spent a double lesson reflecting on the experience through discussion and writing. One conversation that stayed with me was with Adam, who noted how often words like “lucky” and “fortunate” came up in our reflections on Peter’s survival. In truth, what Peter endured was harrowing, and Adam insightfully observed that our digital world may sometimes desensitise us to such stories. Engaging in honest discussion allowed us to challenge these biases, critique our initial responses, and deepen our understanding.

As teachers, moments like these are golden. The Year 10 English team left the museum grateful not only for the patience and generosity of the survivors and staff, but also for the maturity and openness our students brought to this encounter. It is an experience that continues to resonate long after leaving the museum.

Adam D's reflection - Year 10

Peter’s family applied for visas to many countries such as New Zealand, but Australia was the first to get back with the visas. They took a ship to Australia where Peter made many memories. He arrived in Fremantle, Perth and shared a memory he made getting off the ship and going to a milk bar. At the milk bar he has his very first milkshake.

Peter’s first school had children of all different ages and nationalities. The language that was taught was English. However, Peter’s parents were told that education was very important, so they moved him to a new school. To afford the school, Peter’s parents worked three jobs each providing themselves and Peter a good life. Peter was bullied for his appearance at the new school, for his accent and food choices. Peter stated, "I enjoyed being bullied like everyone else, I wasn’t being bullied because I was Jewish”.

What I left with was a strong idea of Peter's experience after the holocaust and his attempt to return to normal life. His thoughts on coming to Australia and being discriminated against were almost appreciated, when compared to his experiences in Europe. It was a strange way to think about it, but it links to what we looked at in class and how damaging dehumanisation is. He had gratitude for his new experiences.

Molly H's Reflection - Year 10

In 1937, Bratislava, Czechoslovakia, Peter Gaspar was born to Emerich and Jenny Gaspar. This was during the rise of the holocaust. His family were non practising but still targeted for their Jewish heritage. Peter was subjected to discrimination for nothing but his race, forced to wear the arm band and denied an education. As the situation worsened, Peter and his family were forced into hiding. He was just 4 at the time.

It was through the help of those brave enough, that they were able to avoid discovery. Neighbours and allies became their lifeline. Peter and his parents spent three years hidden in crammed and enclosed spaces. They stayed in cupboards, and roofs and areas no bigger than a grave for 24 hours of each and every day. The only comfort was found in each other alongside the daily warm meal they shared. In the chilling winter of 1944, Peter became ridden with a fever, and his family were forced to turn themselves in. Peter and his mother were sent to a transit camp, while his father was separated to a labour camp. Five months later, Peter was liberated and reunited with his father. They found a new life for themselves in Australia, yet the horrors of the holocaust remained with them.

In truth, Peter and his parent’s survival was near impossible. They defied all odds weighed against them. Yet it was no miracle, but through the humanity of those willing to risk their own safety. At a time where hiding Jewish people would have you shot on the street, these perilous acts allowed Peter and his family to survive, giving them hope of a future. It is thanks to them, that Peter was able to find a new life, and that his story was able to reach so many. The upstanding morality of many who remain unknown is the truest act of humanity’s spirit and has highlighted the importance of taking action even when others remain silent. In dire times, doing nothing is just as dangerous as the violence itself.

I found it honourable, Peter ‘s courage to dedicate life to sharing such a painful part of his history. Something that had already taken so much from him. It has been the utmost privilege to hear it firsthand. Seeing him face to face made this terrible part of history feel so real. It was no longer words in a book or images on a screen. It was alive, and through someone I could directly speak to. Peter continues to carry the burdens of his past, not just as a survivor but a man of unbreakable integrity. A living warning for us all. Knowing my generation is the last to witness such a story, firsthand, deeply saddens me.

From this, I feel an obligation to speak out. Though I will never grasp what millions endured under the Nazi regime, it is a duty to continue to pass down these messages to coming generations. These conversations, though often uncomfortable, are necessary in ensuring the atrocities of the past are not repeated. We cannot afford to forget what happened. We cannot afford to forget the countless lives lost, not as a mere percentage, but as individual human beings. Peter’s words have deeply resonated with me. To stand silent is to enable chaos. I take on the responsibility of not just standing by but enacting injustice and I urge it on all.