Wellbeing News

TEENS and SCREENS

Below is a link to an interesting article about teens and screens. This article presents both the pros and cons of video games.

Over the past several years, some students from Glen Innes High School have participated in research called the “Future Proofing Study.” Dr Lyndsay Browne summarises the findings from this study, in relation to screen use and mental health, in the article below.

Screens, teens, and mental health

Findings from the Future Proofing Study + 5 recommendations

Introduction

The digital revolution has permeated every aspect of our lives, reshaping how we think, work, and interact. While many of these changes offer us improvements and convenience, the critical focus lies in HOW individuals and society navigate and embrace these transformations. Adolescents are 'digital natives' exhibiting distinct cognitive processes shaped by their lifelong exposure to technology. Their youthful neuroplasticity and receptiveness to innovation align closely with technological advancements, amplifying the impact of digitalistion on their lives.

In tandem with the digital surge, global megatrends like climate change awareness and urbanisation, compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic, have underscored psychological challenges among adolescents, evident in escalating distress levels over the past decade. Statistics from the Mission Australia and Black Dog Institute Youth Survey reveal a steady rise in distress among Australian adolescents, from 19% in 2012 to 29% in 2022. This increase occurs amidst the various challenges of adolescence, a pivotal period characterised by ongoing brain development, peer influences, and heightened sensitivity to dopamine. This underlines the importance of understanding the interplay between mental health and technology usage during this formative stage.

What are we learning in the Future Proofing Study about adolescent digital usage and mental health?

The Future Proofing Study, conducted by the Black Dog Institute, is the largest and most comprehensive longitudinal study of adolescent mental health in Australia. It involves thousands of the same group of students completing annual, online surveys for 6 years during their adolescence.

What are we finding out about the association between screen time and mental health?

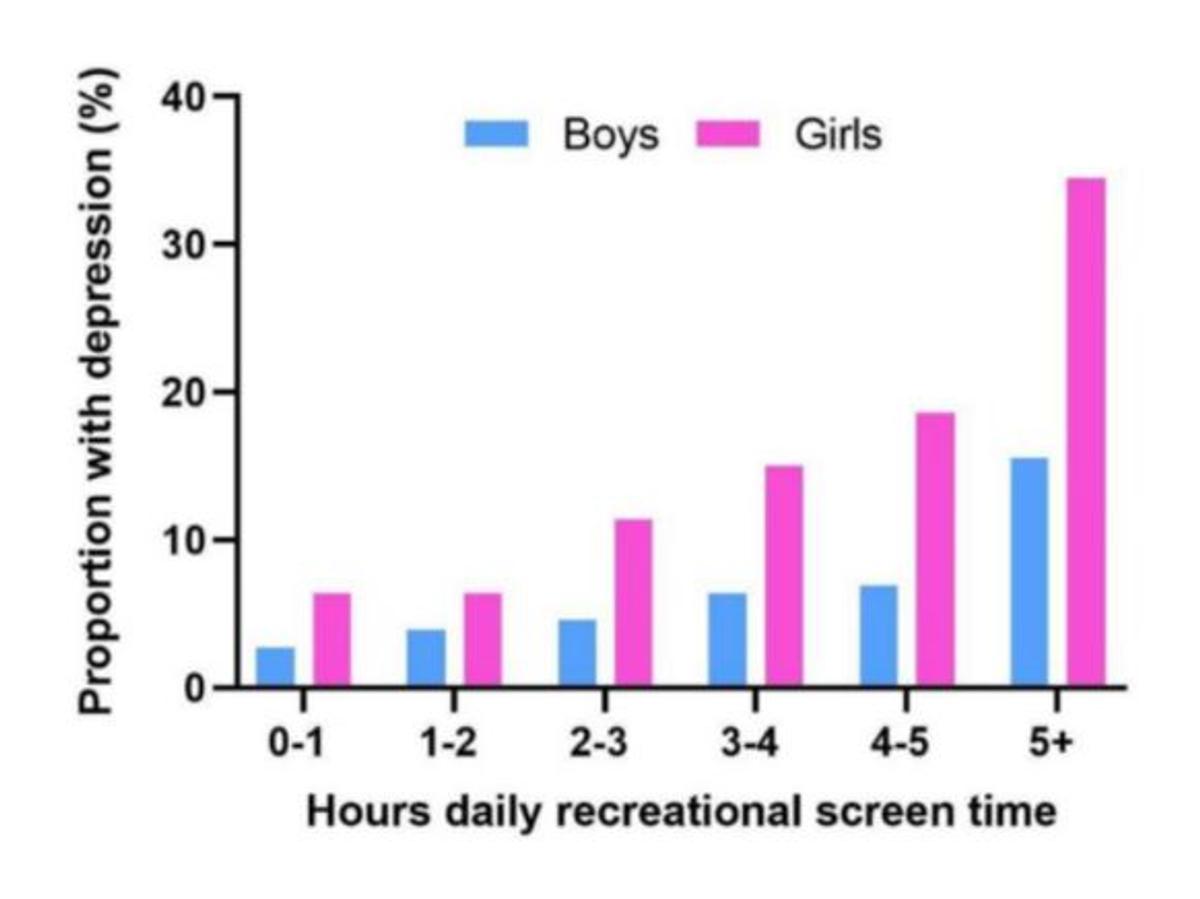

Analysis of data from the surveys completed by all 6400+ participants when they were in Year 8 shows the following association:

As we can see, the data reveals a clear correlational link between increased screen time and higher likelihood of young teens meeting clinical levels of depression. The graphs for anxiety and psychological distress look very similar.

However, correlation is not causation. Although research has not established a definite causal relationship between social media use and mental health issues, several studies indicate a bidirectional influence over time. This means screen use and mental health impact each other: feeling low can lead to increased screen time, which might further affect mood due to reduced physical and social engagement, as well as exposure to negative online content like body image comparisons or cyberbullying.

In addition, as we know, mental health conditions cannot be solely attributed to a single contributing factor: they have a multifactorial origin, arising from the convergence of various individual and environmental circumstances. Additionally, the presence of protective factors (such as supportive family relationships) plays a crucial role in determining the development of these conditions.

Current research indicates that to clearly understand the link between technology use and adolescent mental health, it's crucial to examine the specific online content and activities adolescents are involved in, rather than treating 'screen time' as a single concept. Additionally, of course, considering an adolescent’s individual circumstances is essential for a complete understanding.

We do wish to flag that longitudinal research studies like the Future Proofing Study are just beginning to find that, in fact, mental health challenges problems such as depression and anxiety are predictive factors for higher numbers of screen hour usage daily, in other words, teens experiencing mental health issues such as depression and anxiety are more likely to spend many hours on screens each day than teens without depression or anxiety. This is counter to the popular belief that spending large amounts of time on screens each day is a predictive factor for teens developing mental health problems like depression and anxiety. In other words, it seems increasingly the case that longitudinal studies are finding that teens with depression and anxiety come to use screens excessively rather than that excessive screen usage causes teen anxiety and depression.

However, what teens do online remains relevant to our understanding of the relationship between screens and teen mental health so let’s look at how adolescents are using screens.

What have we found out about how teens use screens?

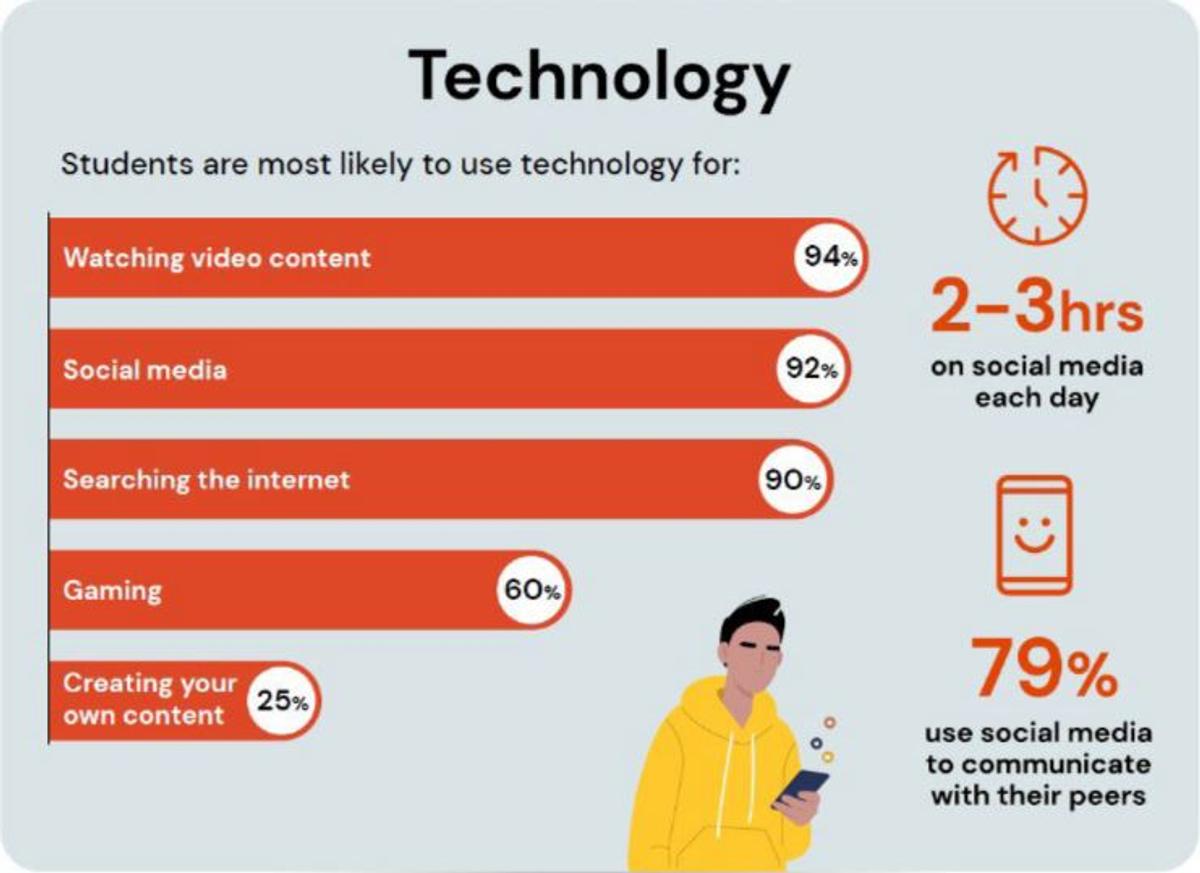

In their Year 10 surveys, students reported that they use technology in the following ways:

Participants using social media included Instagram as their most frequently used app with 79% of all students using it once or more each week, followed by Snapchat at 74%, and then TikTok at 67%.

We also asked detailed questions about HOW young people are using social media in particular and learned that 79 % of students use social media to communicate with real-life peers. Relatively few students reported that using social media stopped them from seeing their friends in real life. Other international studies report that teens often have social gatherings that include both virtual friends online, such as on FaceTime, and friends in person so that they spend time online with virtual friends while simultaneously hanging out with other friends who are physically present. In other words, these social gatherings consist of both virtual and non-virtual participants. For most adolescents, there is no longer a distinction between online relationships and offline relationships; there is now what Benvenuti et al (2023) describes as ‘onlife’ as their relationships merge into a dimension largely unfamiliar to prior generations.

Clearly, we need robust longitudinal data to better understand the nuances of this relationship between adolescent mental health and screen use (this will be possible with the Future Proofing longitudinal data in the next few years).

How can we support adolescents to thrive while they navigate the digital revolution?

So, how can we positively support adolescents who are living in a highly digitalised world and who may be struggling psychologically? Truth be told, we are all pioneers here because we don’t yet have evidence informed programs available about the impact of technology use. We examined the latest research in order to identify successful strategies for working with young people. These included:

1. Acknowledging and valuing digital experiences for teens

According to research, when adolescents are not feeling defensive and judged about their screen use, they will talk about how social media and gaming serve as stress relievers, distractions from daily pressures, a central way to maintain friendships aer school, an avenue for learning new skills like soware coding and expressing their creativity via vlogging or blogging or posting.

2. Providing targeted support to already at-risk adolescents vulnerable to the impacts of screens

Research shows that vulnerable young people who ‘come to screens’ with pre-existing mental health problems are frequently negatively affected by screens. And, according to research, adolescents recognise that the digital landscape presents significant challenges for young people, including exposure to disturbing content such as self-harm, negative online communication with peers, pressure to conform to unrealistic beauty standards, and gaming addictions, all of which can worsen existing mental health struggles.

So we need to continue to work proactively with young people who are already vulnerable in order to protect them from the negativity that can be associated with accessing social media. These interventions need to be approached delicately, however, since the challenges these individuals face often mean that they also benefit from the support, information, help, community, recognition, and sense of belonging available online.

3. Teaching digital technological literacy

Starting in primary school, the school curriculum needs to consistently educate students about the profit-driven tactics used by major technology companies like Instagram, YouTube, and Snapchat. This is vital to enable children, pre-teens and teens to recognise persuasive techniques, algorithms, targeted advertisements, biased news, and addictive features, and to encourage them to engage with social media platforms critically. They can learn techniques to proactively shape the algorithms on their social media so that they are actively choosing content that adds to their lives – techniques like using the ‘likes’ and ‘hiding’ features on their social media apps; seeking out pages that positively influence them; and unfollowing pages that negatively affect them.

In this learning process, a nuanced approach that steers clear of the simplistic 'helpful' vs 'harmful' approach to social media and technology will land more effectively with adolescents – and, more accurately, also reflect the reality of the intricate and multifaceted nature of adolescents' online interactions.

Beyond the formal curriculum, another approach to behavioural change is for senior students to engage with younger students about screen use. Studies show that social media use is more problematic for younger adolescents, with older adolescents able to demonstrate more self-control than the youngsters so older adolescents,

senior students in a school, who are also digital natives, could successfully mentor the younger students at school in how to manage their social media use.

A few useful resources for teaching digital literacy:

4. Role modelling a balanced approach to technology and social media use

Leading by example is crucial: when adults prioritise quality time away from devices, adolescents are more likely to follow suit. And seeking opportunities for enforced offline stretches of time are possible – and very helpful.

5. Engaging in indirect prevention approaches

Indirect prevention in health entails focusing on addressing social, economic, and environmental factors to reduce disease risk and promote overall well-being. In our efforts to prevent adolescent mental health problems, indirect prevention strategies include implementing well-being education in schools, promoting healthy peer relationships, encouraging regular physical activity, providing balanced nutrition, creating safe spaces, teaching the importance of good sleep, funding family support programs, offering accessible counselling services, and focusing on building adolescent self-esteem. In particular, it is worth focusing our energy on sleep education given all the evidence-based research showing that screens before bed is having a significant negative impact on the quality and quantity of sleep and hence on physical and mental health.

Prioritising these strategies is essential for the prevention of adolescent depression and anxiety which will reduce adolescent susceptibility to the challenges of problematic screen use, especially social media.

Conclusion

The digital realm has become an expansive network of opportunities for adolescents, who now not only live in an internal and external world, but also in a virtual world. Collaborating with them around screen and technology use is essential if we are to equip adolescents with the skills to navigate this landscape with their well-being intact and with the requisite technological skills that they will undoubtedly need in their adult lives.