Teaching & Learning Page:

Web Pages:

Deep YouTube

My daughter told me about Astronaut.io. It’s a website that plays a few seconds of random YouTube videos with almost no views — like this video of a cafe in Vietnam with 1 view, and this one of goats eating weeds near a freeway in rural Japan with 0 views. After a few seconds, it starts playing another video. It’s addictive. Many of the videos aren’t in English, which is a plus for me.

Feel connected to the Universe

This helps you get out of your headspace for a bit:

NASA’s What Did Hubble See on Your Birthday? Enter all the important dates you can think of and go down a Wikipedia wormhole to learn more about the Sombrero Galaxy and light echos. Every image is awesome and uplifting.

Techie Tips:

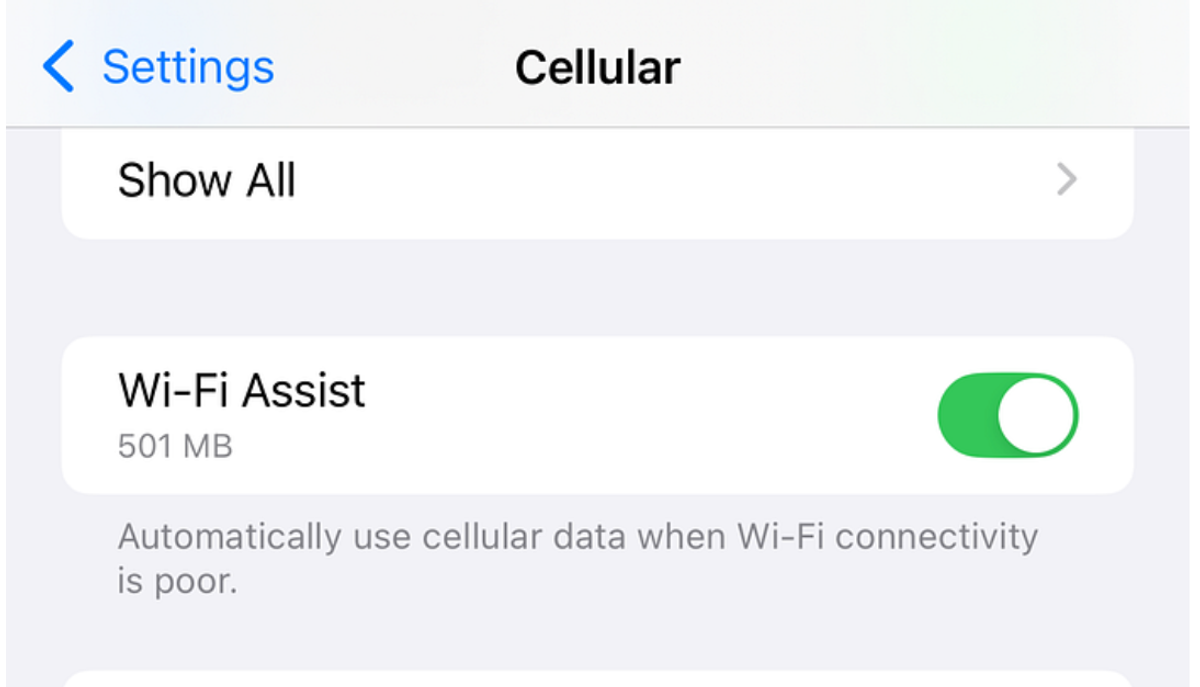

Enable Wi-Fi Assist to Avoid Dropped Connections:

Ever leave your house, and suddenly your music or podcast stops because Wi-Fi clings

to a weak signal? Wi-Fi Assist fixes that by seamlessly switching to cellular data when

your Wi-Fi connection falters. Here is how to turn it on:

1. Go to Settings - Cellular, and scroll down to Cellular Data options.

2. Flip the switch next to Limit IP Address Tracking and turn it on.

This setting ensures your streaming, calls, or browsing don’t skip a beat when

transitioning between networks. It is especially handy when you are heading out the door

or moving between rooms with spotty Wi-Fi.

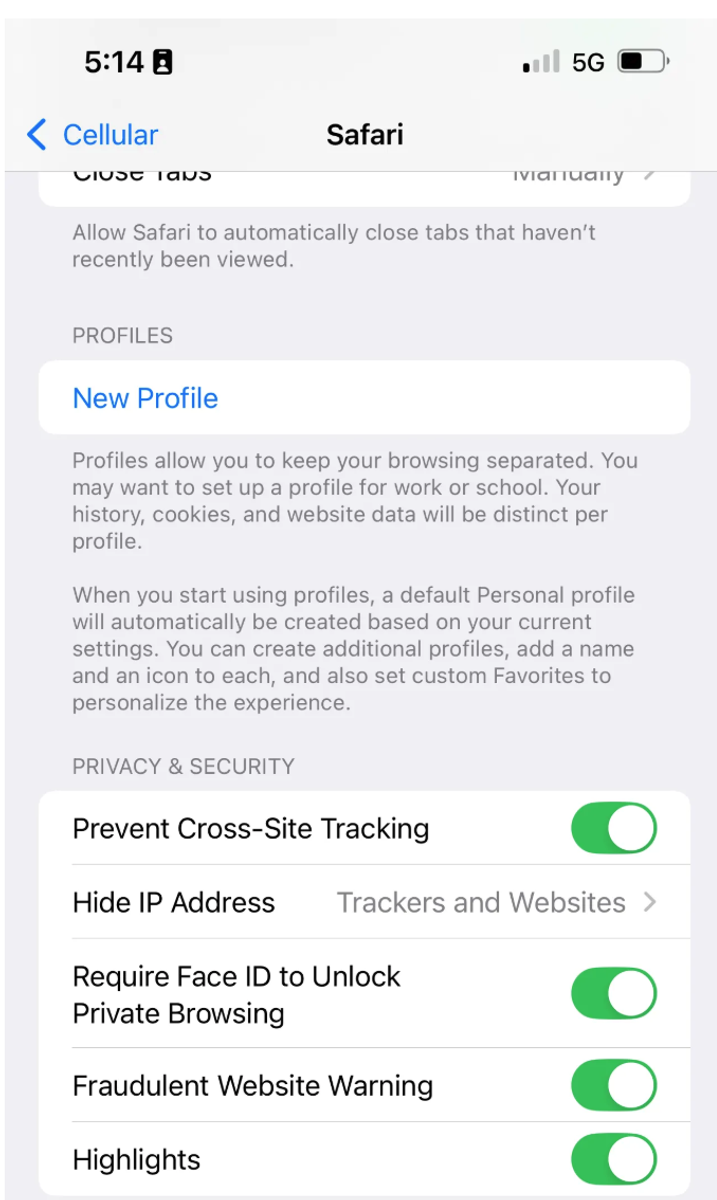

Turn on Highlights in Safari For Smarter Browsing 🌐

If you use Safari as your primary browser, the new Highlights feature in iOS 18 will

make your browsing smarter. It uses Apple Intelligence to give you rich, contextual

information while browsing. To turn on the highlights option,

1. Open Settings, scroll down to and search for Safari.

2. Tap Safari, scroll down, and toggle Highlights to On.

With Highlights active, you will get quick insights into locations, people, and even shows

on Apple TV. Some websites also include summaries and tables of contents to make

navigation easier.

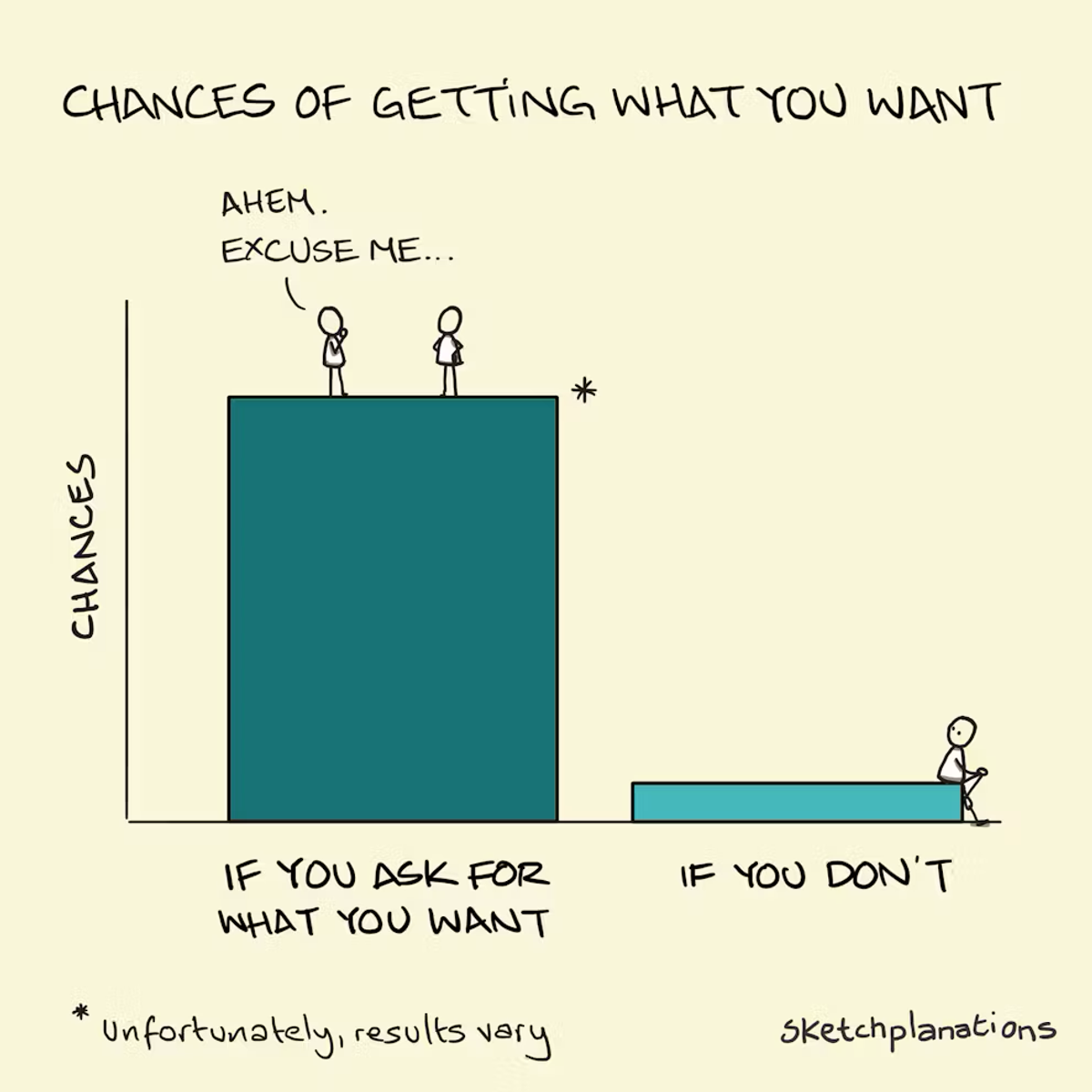

Sketchplanations :

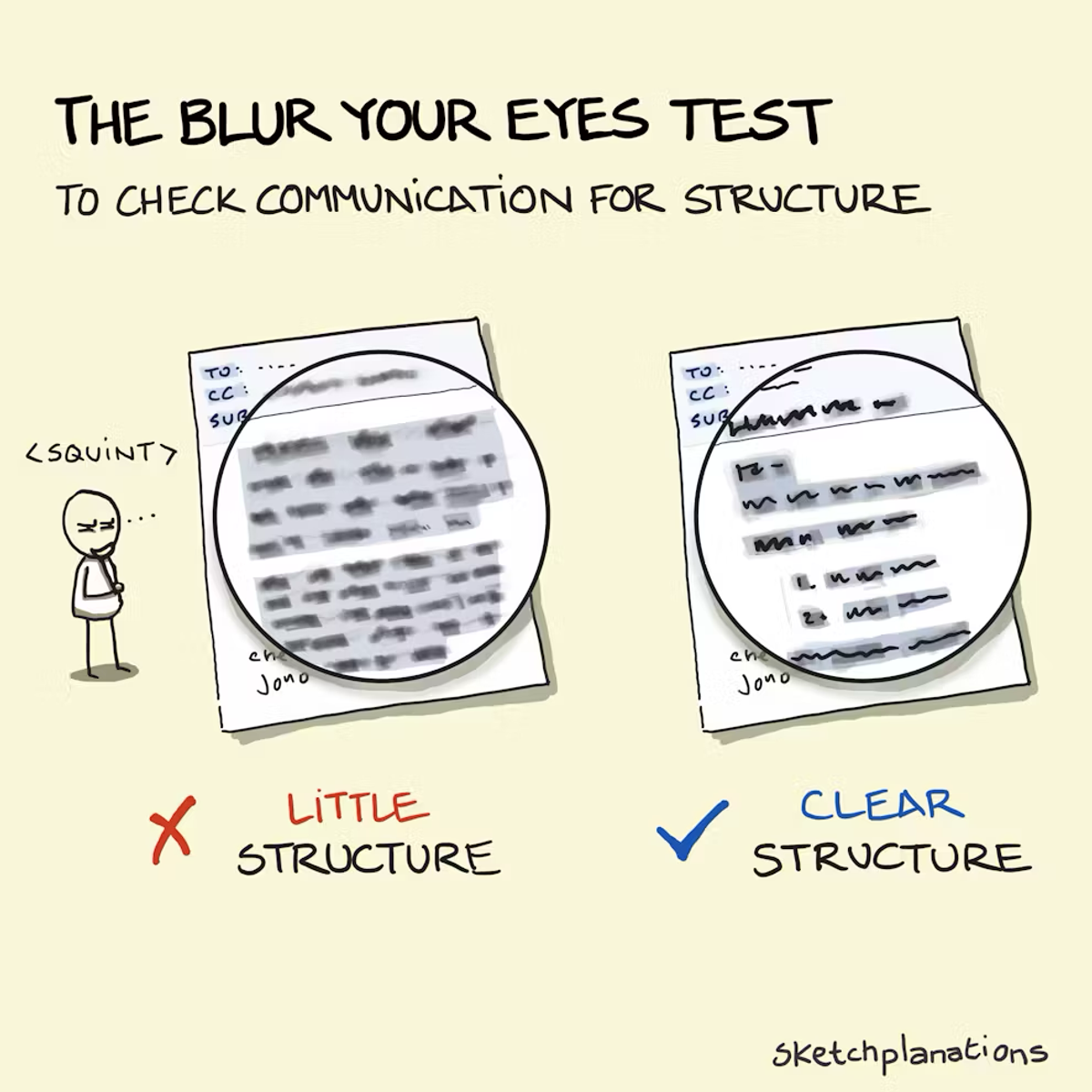

The blur your eyes test is a way to evaluate the big picture and clarity of communication and designs by squinting to blur your eyes.

Good designs give you a sense of the structure, even through a blurry lens. Poor designs leave you no wiser.

Communicating with Busy People

I spent a little time with Stanford design Professor Larry Leifer. Like all Professors, people constantly inundated him with requests for his time and expertise—I sometimes wonder how talented academics cope. If you were writing to him—or anyone—you could help him and yourself by being clear.

Clear was not just in the message and the words you wrote but also in the structure of your writing. He told me that he felt you should be able to narrow your eyes to blur your vision and still see the basic structure of an email: greeting, intro or context, ask, sign off. Well-structured emails were more likely to get his attention and response because you'd made it easy for him to deal with.

I've applied that tiny snippet of advice thousands of times since when writing emails, Slack messages, product releases, announcements, invitations, page designs, banners, chats and articles. As I reviewed more and more designs, I would use it to check, "Are we making this easy for the reader?"

Using the blur-your-eyes test

The blur your eyes test is a practical first screen for evaluating most communication, even if you don't consider yourself a designer. It works because it's simple and tests whether you're making life easy for the reader.

To try it, head to a well-designed web page and squint until your vision is blurred. Can you still get an idea of the page even without seeing the details?

If I blur my eyes, where do I expect the key message to be, and what are the supporting messages? Where do I expect to click if I want to continue? My team probably got sick of me squinting my eyes, asking them to do the same, and reporting that it wasn't apparent to me what to expect.

Because people naturally skim content, making it as easy as possible to understand your message is essential. Clear hierarchy. Obvious next steps. It's also why Happy Talk Must Die and why wireframes and low-fidelity prototyping are helpful.

And yes, I also use it for Sketchplanations. Try blurring your eyes on past sketches and see if you think they pass—I'm sure I don't always manage it. It's also part of why I love the idea sketch format on which I've based so many sketches.

The blur-your-eyes test works to communicate with busy people—and we're all busy people when we're trying to find what we want on the internet.

As a separate lesson, another Stanford Professor, Bernie Roth, also taught me that a short, polite, timely rejection is much more valuable than a delayed, in-depth rejection.

It took me a long time in my professional life to learn that my chances of getting what I wanted increased significantly if I asked for it.

It seems obvious, but somehow, between politeness, awkwardness, fear of rejection, or humility, I forgot. As a child, I had no hesitation in asking for things. But somewhere along the way, I got out of the habit.

Like in a relationship, asking for what you want avoids others having to guess—and potentially getting it wrong. If no one knows what you need, it's easy to feel overlooked, even when no one meant to ignore you.

That's not to say asking is easy or without risk. Social norms, power dynamics, and biases mean that the same request can be received very differently depending on who asks. In some cases, asking outright might even backfire. But when possible, asking remains a powerful tool.

Sometimes, asking is an obligation. If you're seething with resentment because you stayed late at work when you really needed to be back early today, that serves no one very well. You might do a worse job and be unhappy to boot. If there's something you need to be happy in your job and your manager doesn't know, it's hard for them to help.

Twenty years ago, my wife and I went on an expedition to climb Mt Kenya. As we reached camp on the second day of hiking, one group member shared that he couldn't eat any foods containing gluten. By then, finding alternatives was challenging—the meals had been planned and packed days before—and jeopardised the whole trip.

To ask for what you want, you must first figure out what you want. This isn't always straightforward, and it's easy to drift along without thinking about what you'd like and where you want to go. Doing the hard work to figure that out helps you and those you work with when planning and opportunities for change arise.

You might never get what you ask for. But I've found that even when I didn't get what I wanted at the time, I sometimes got what I asked for later. When people know what you're looking for, they're more likely to think of you when the right moment comes.

Article:

As a Professional Editor, I Can Strengthen Any Writing Using 6 Rules

1. Cut out any unnecessary words.

Our college courses did us dirty. Professors encouraged students to hit minimum word counts, so we threw in as much filler as possible — but quality writing is clear and concise. That’s why most literary agents will instantly reject manuscripts that are over the recommended word count for their genre.

In his book Editor-Proof Your Writing (affiliate link), veteran editor Don McNair has an entire section dedicated to taking words out:

The more words you eliminate without changing meaning and sacrificing detail, the clearer and more powerful your writing will be. [… The] words we want to chase away do specific, bad things to our writing. Examples? They weaken verbs. They introduce author intrusions. […] They create redundancies.”

- Do you have two words that mean the same thing? (She was a stunning,̶ ̶b̶e̶a̶u̶t̶i̶f̶u̶l̶ woman.) Take one out.

- Can the reader tell who’s speaking without the dialogue tag? (“Are you sure you want to do that?” I̶ ̶r̶e̶s̶p̶o̶n̶d̶e̶d̶̶.) Delete it.

- Are actions already implied by other actions? (He t̶u̶r̶n̶e̶d̶ ̶h̶i̶s̶ ̶h̶e̶a̶d̶,̶ ̶l̶o̶o̶k̶e̶d̶ ̶a̶t̶ ̶m̶e̶,̶ ̶a̶n̶d̶ ̶ beamed at me.) Cut them.

2. Choose strong verbs instead of weak verbs + adverbs.

Similarly, some writers try to strengthen a weak verb by combining it with an adverb. Instead, choose a strong verb from the get-go.

- I ran quickly out the door = I sprinted out the door.

- She cried softly = She whimpered.

- He thought deeply about the idea = He pondered the idea.

- They ate it greedily = They devoured it.

The same rule applies to adjectives and nouns: A big house is a mansion. A tall building is a skyscraper. A heavy rain is a downpour. If you can find a stronger term that encapsulates the idea in fewer words, use it.

3. Use active voice whenever possible.

An editor from a publishing house taught me this tip. It took me a while to grasp, but I saw passive voice everywhere once I did.

What’s the difference between active voice and passive voice? In active voice, the subject performs the action on the target: “The cat chased the mouse.” Here, the cat is the subject and the mouse is the target.

In passive voice, the writer prioritizes the target of the action over the subject: “The mouse was chased by the cat.” The mouse isn’t the subject; it’s the target, but it still comes before the subject and the verb. The sentence now contains unnecessary words, like “was” and “by,” which makes it longer and weaker.

- The cake was eaten by the children = The children ate the cake.

- The speech was given by the president = The president gave the speech.

- The window was broken by the storm = The storm broke the window.

When identifying passive voice, keep an eye out for the phrase “there was.” People use it constantly to passively describe a scene — but if you think about it, it doesn’t make much sense. When a sentence starts with “there was,” who or what is the subject?

- There was a book on the table = A book lay on the table.

- There was a decision made by the board = The board made a decision.

- There was a letter found in the archives = The librarian found a letter in the archives.

4. Search your document for filler words and delete 99% of them.

Some words in the English language serve virtually no purpose — and yet most of us use them all the time.

The word “just” is a great example. In 99% of cases, it’s unnecessary. It doesn’t change the sentence's meaning, but we just throw it in anyway. (Not-so-fun fact: Women subconsciously use it more than men to soften their language so they seem polite and apologetic.)

- He just couldn’t believe the outcome = He couldn’t believe the outcome.

- I’m just checking in about those documents = I’m checking in about those documents.

- No matter how hard she practiced, she just couldn’t do it = No matter how hard she practiced, she couldn’t do it.

When I searched my first manuscript for the word “just,” I had used it over 300 times. Deleting most of them didn’t change the meaning of my sentences, but it did make my writing stronger.

Other common filler words that rarely serve a purpose?

- That

- Really

- So

- Very

- Actually

- Of

Pro tip: If you press Ctrl + F on your keyboard, you can search most documents and web pages for specific words and phrases. Use this to find and delete filler words.

5. Ditch your thesaurus and opt for clarity.

Novice writers beef up sentences with as much flowery language as possible. Professional writers know that writing is a form of communication, and communication should be straightforward.

No one thinks you’re smart because you use words like “pontificate” and “ostensibly.” Instead, they probably think you’re an asshole.

Unless you’re writing a legal document or trying to impress the guy who does your taxes, ditch your thesaurus and use clear, powerful language. Take your time to find the right word, but don’t choose a word solely because it sounds impressive. In fact, writing long sentences with big words is the fastest way to lose your reader.

It doesn’t matter how impressive your writing sounds if the reader gives up before learning anything.

6. Read your work out loud — or have AI do it for you.

Last but not least, read everything you write out loud. It’s the easiest way to catch mistakes — but it’s not only about grammar.

Like music, beautiful writing has a cadence to it. That’s why Shakespeare wrote in iambic pentameter and Emily Dickinson used slant rhyme. When you read your work out loud, you’ll know if that cadence is there. On the other hand, when you’re tripping over your words, it’s time to make some edits.

If you don’t like reading aloud or you share a workspace with others, put on headphones and use the Read Aloud feature in Microsoft Word. (It sounds robotic, but it gets the job done.)

Alternatively, you can use AI text-to-speech software to read articles, web pages, and more. I use an extension called NaturalReader. It’s pricey and has a few glitches, but it sounds pretty damn realistic.

Happy editing, and remember: If the sentence makes sense without it, it’s j̶u̶s̶t̶ not worth the word count.

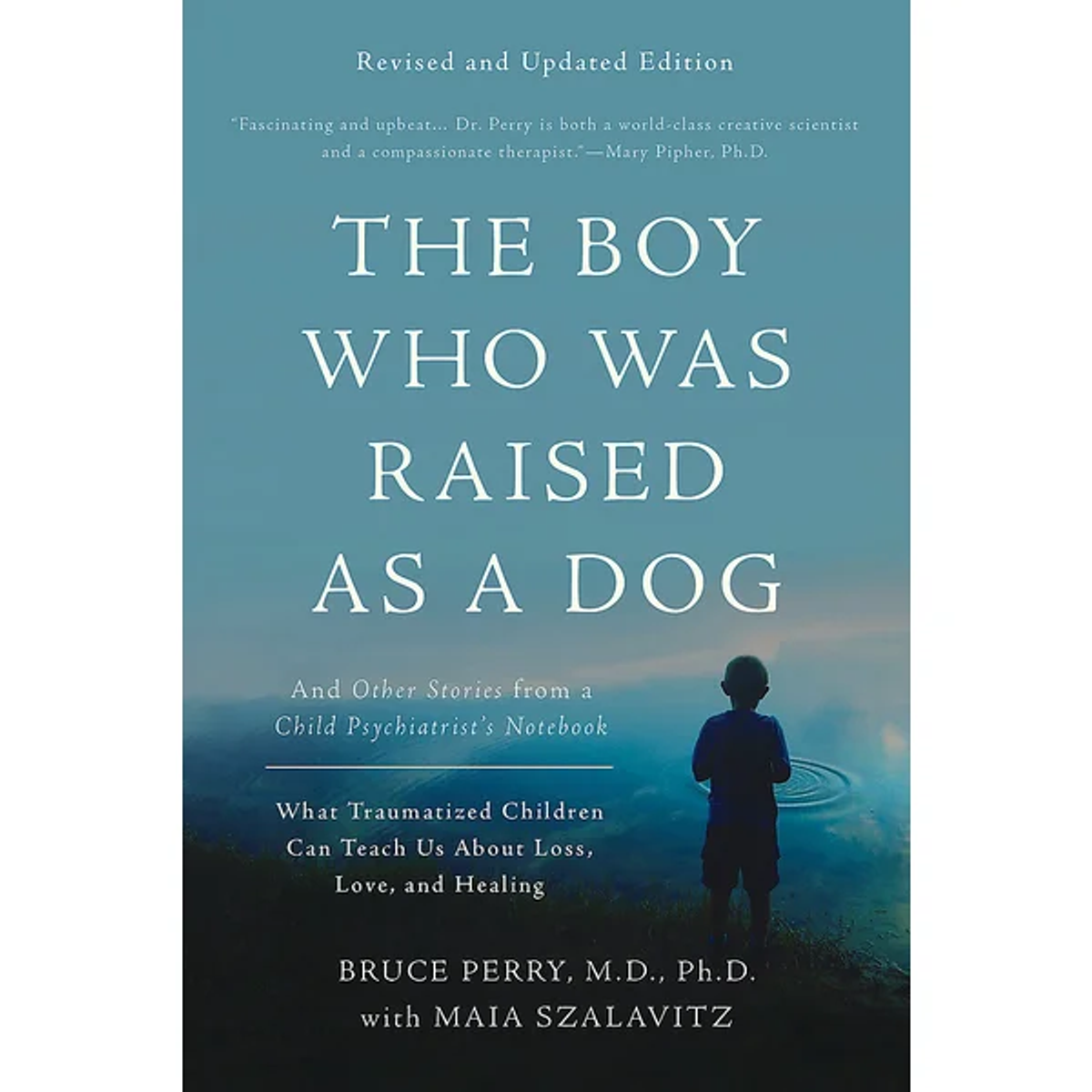

Book Recommendation:

What happens when a young child is traumatized? How does terror affect a child's mind, and how can that mind recover? Child psychiatrist Bruce Perry has treated children faced with unimaginable horror: homicide survivors, witnesses to their own parents' murders, children raised in closets and cages, the Branch Davidian children, and victims of extreme neglect and family violence. In The Boy Who Was Raised as a Dog, Dr. Perry tells their stories of trauma and transformation. He explains what happens to the brain when children are exposed to extreme stress and trauma and reveals his innovative (non-medicinal) methods for helping to ease their pain and allowing them to become healthy adults. In this deeply informed and moving book, Perry shares with the reader the lessons of courage, humanity and hope he learned from these scarred children. He dramatically demonstrates that only when we understand the science of the mind and the power of love and nurturing, can we hope to heal the spirit of even the most wounded child.