Teachers' Page:

We start each week with a Monday Morning Meeting for staff. It's a time for information sharing, celebrating staff and children's achievements, laughter, building and strengthening the kaupapa foundations for our school, and a few tips on teaching, techie skills and even life. This page will be the place teachers can come back to if they want to revisit anything we covered in our Monday Morning Meetings.

It's really a page for teachers, but if you find anything worthwhile here for yourself, great.

Web Sites:

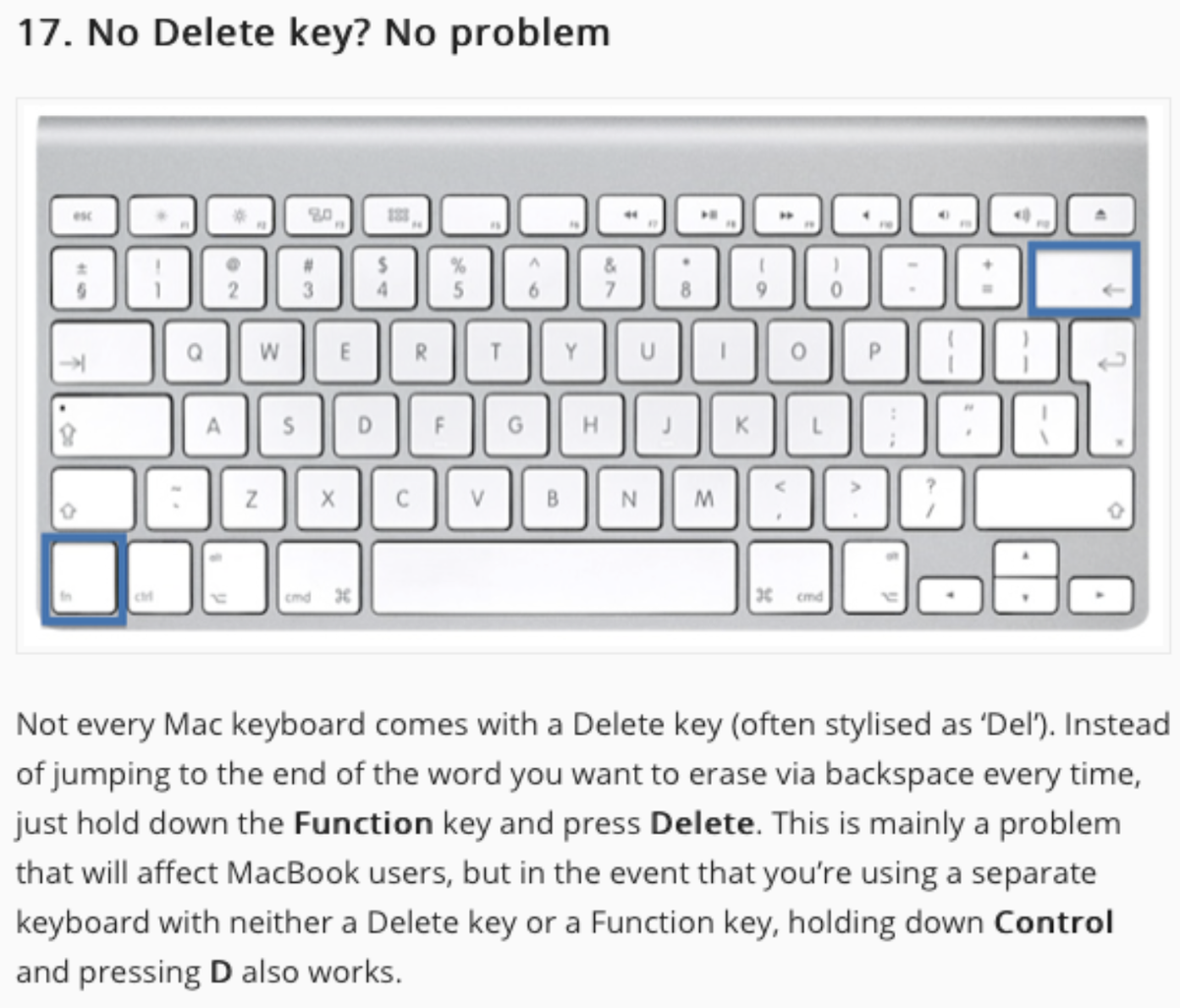

Techie Tip:

Google Tips:

Save time on your documents

1. Create a new doc instantly

Type doc.new in your browser’s address bar and you’ll have a new document.

This works in Chrome, Firefox, Safari, and Arc.

Bonus:

You can also type sheet.new, slide.new, form.new, site.new, drawing.new, or cal.new to create instant Google spreadsheets, slides, forms, sites, drawings or calendar events.

2. Translate your text automatically

Share your doc in another language. Your original is preserved — GDocs creates a translated copy. It’s not human quality, but it’s good enough to convey the gist of your message.

Note:

For a good translation alternative, try DeepL.How: Go to Tools > Translate document.

3. Add a table of contents

For long documents, add a clickable outline at the top to make it easy to jump immediately down to any section.

How:

Go to Insert > Table of Contents

4. Display a live word count

Show a persistent count at the bottom left of your editing window.

How:

Go to Tools > Word count— or Command-Shift-C — and check the box for “Display word count while typing.”

5. Type with your voice

This works well when you’re tired of typing. Instead of facing a blank page, think out loud, then edit your dictated draft.

How:

Go to Tools > Voice typing

6. Type @ to quickly add elements to your doc

This new feature lets you add checklists, numbered lists, and bulleted lists more quickly. Or insert images, tables, and charts.

How:

Type @ for a keyboard shortcut to insert whatever you need, rather than hunting through menus with your mouse.

7. Add email drafts and project trackers inside your doc

Inspired by Notion & Coda, GDocs now lets you insert “building blocks.”

These include mini-templates for meeting notes and tracking content. One block lets you create an email draft. You can collaborate on it in a doc, then send in Gmail.

How:

Type @ and choose the block you want.

Improve your doc’s appearance

8. Add a gif to show how something works

Gifs are a nice way to get around being unable to embed videos in a doc. Make gifs with Giphy or use Zight to record a screen capture as a gif.

How:

Go to Insert > Image and select your gif to add it to your doc.

9. Create a highlighter effect

Make important text stand out by adding a colour to it.

How:

Select text, click the highlighter button & pick bright yellow for example.

10. Use bigger fonts

Bigger text is easier to read. People will appreciate the readability of your docs. Use size 14 if you can get away with it.

11. Try Georgia, Raleway, Proxima Nova or Oswald

These fonts are easy to read, elegant and professional.

Tip:

Use WhatTheFont or WhatFontIs to identify nice-looking fonts on other sites.

How:

For more font options in GDocs, click the font button on the tool palette and then More fonts to add alternatives.

To learn more & try out styles:

Google Fonts.

12. Break text into sections

Use horizontal line breaks to clean up long docs.

How:

Use Insert > Horizontal line

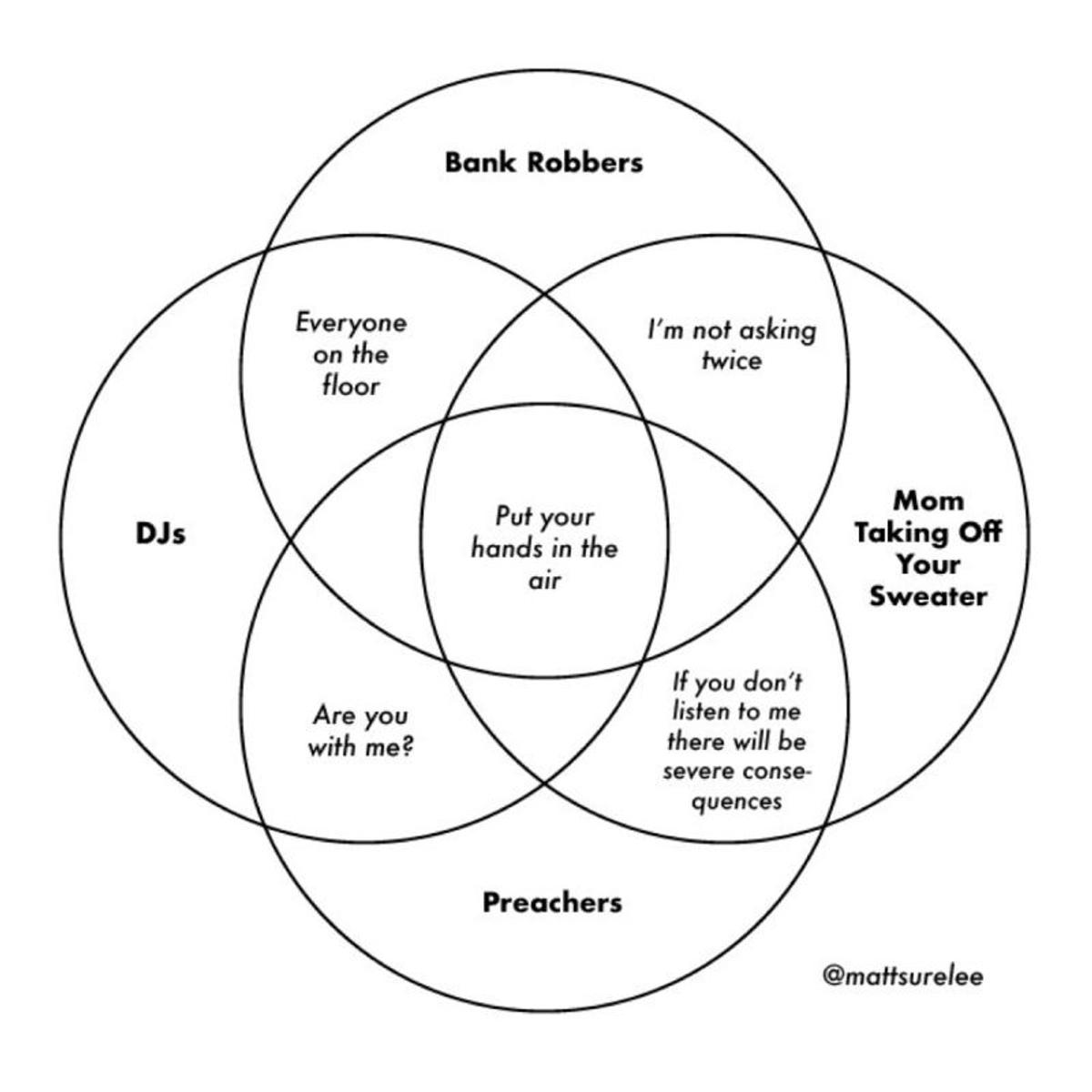

One of the Coolest Venn Diagrams Ever:

Sketchplanations

Twitter co-founder Biz Stone is fond of saying:

"Timing, perseverance and ten years of trying will eventually make you seem like an overnight success."

Rarely have I heard someone so clearly articulate both what it usually takes to do well at something and how commonly we misrepresent the path to success.

Steven Pressfield On Determination:

"I’ve seen a million writers with talent. It means nothing. You need guts; you need stick-to-it-iveness. It’s work, you gotta work, do the freakin’ work. That’s why you’re gonna make it, son. You work. No one can take that away from you."

Writing is the process by which you realize you do not understand what you are talking about. Of course, you can learn a lot about something without writing about it. However, writing about something complicated and hard to pin down acts as a test to see how well you understand it. When we approach our work as a stranger, we often discover how something that seems so simple in our heads is explained entirely wrong.

What's ONE thing you can do today that makes tomorrow easier? Repeat.

Become a Better Facilitator With 5 Tips for Improving Your Active Listening Skills:

The ability to be an active listener is pretty much a non-negotiable for facilitators, but that

doesn’t mean the skill comes naturally to everyone.

When it comes to communication, what tends to be most in line with human nature is:

- Thinking ahead to what you’re going to say / how you want to reply

- Interjecting or jumping in to respond even if you’re not able to play back what you heard

- Reacting before filtering your thoughts or gut-checking them against personal bias, triggers, and baggage

These behaviours are pretty standard, which is why active listening is all about building

muscle memory.

Active Listening can generally be understood as a method for listening and responding to another person — both verbally and nonverbally — that increases empathy, understanding, and alignment between people.

You can see why it’s so important to the field of facilitation: facilitators listen to people all

day long! And it’s up to us to receive information, synthesize it, play it back, and paraphrase what we’ve heard.

Why? It builds trust, drives understanding and collaboration, and helps teams align and gain clarity (which is likely something they’ve struggled to achieve on their own, hence the importance of guidance from a facilitator).

If you want a little support honing your active listening skills, here are 5 actionable tips you can start folding into your facilitation practice to make your sessions a more positive experience for everyone:

1. Release ourselves from needing to have all the answers or being the “boss” of the meeting.

2. Ask questions (even the so-called “dumb” ones), to foster group exploration and democratise participant sharing.

2. Hold eye contact, keep body language open, and don’t check your phone.

3. Don't jump to conclusions or make assumptions about others.

5. Acknowledge contributions, validate ideas, and thank people for sharing — a little kindness goes a long way.

Writing Is A Thinking Tool:

What’s uniquely human that can improve your decision-making, creativity, and productivity

and is completely free?

The answer is: Writing.

To date, we haven’t found any other animal on Earth that has developed any form of writing, whether carved symbols or inked patterns, as a tool for transcribing ideas. We humans are the only ones with access to this powerful tool.

Unfortunately, many of us make use of this tool in only the most basic ways: to send emails, write down a to-do list, or text other people. When, in fact, writing is a superpower that can unlock parts of your mind that are harder to access otherwise.

Your mind on writing

If metacognition is your compass, then writing is your map. By putting down your thoughts on paper, you can navigate them more easily. As such, and especially in our age of information overload, writing is not just a means of expression. It’s a tool for clarity, comprehension, and connection.

1. Writing is a cognitive filter.

Instead of consuming a lot of random content, writing about what you read, watch, or listen to will force you to do some preliminary research to select high-quality sources and become more intentional with your information diet. In this way, writing becomes a filter for what information enters your mind — for the seeds you plant in your mind garden.

2. Writing is the greatest explainer.

“Ce qui se conçoit bien, s’énonce clairement” (“What is clearly thought out is clearly expressed”) once said Boileau, a French writer.

This is the principle behind the Feynman Technique, named after the Nobel prize-winning physicist who has been dubbed The Great Explainer.

“Without using the new word which you have just learned, try to rephrase what you

have just learned in your own language.” — Richard Feynman, Physicist.

When you struggle to write something in your own words, it often means you haven’t

completely grasped the idea. Writing is a sometimes painful way to highlight those gaps:

There is no hiding behind moving your hands in circles and using your most authoritative

voice. If you can write it, you can truly explain it.

3. Writing is a memory enhancer.

The generation effect is where information is better remembered if it is actively created from your mind rather than read passively. Instead of passively taking notes, making notes ensures you are in active learning mode and form connections between new and pre-existing knowledge, making retrieving information easier. And when your memory inevitably fails you, you can always go back to your notes to refresh them.

Bonus tip:

You may even edit your existing notes to rephrase them more memorably.

4. Writing sparks creativity.

Creativity relies on your ability to connect existing ideas together. To form such connections, you need a way to retrieve and explore ideas you encounter or that pop into your mind. Writing is a great way to create such a searchable database of ideas to connect them and generate your own incremental ideas. In addition, while many people have similar ideas, the pathway to these ideas often differs from mind to mind. Writing your thoughts down will help you track the life of your thoughts and provide unique material to produce creative content.

5. Writing is a connector.

Sharing your work multiplies the power of writing. By “working with the garage door open,” as Robin Sloan said—you create a feedback loop allowing you to improve your thought processes, learn something new, discover a different way to tackle a problem, or even make friends with like-minded people. Don’t wait until you have a perfect draft of an article. Share to learn, not to shine.

Writing is more than a practical tool—it’s a way to think better, both individually and collectively. To make the most of it, write more, write often, and share some of your

writing with the world.

Creating your writing practice

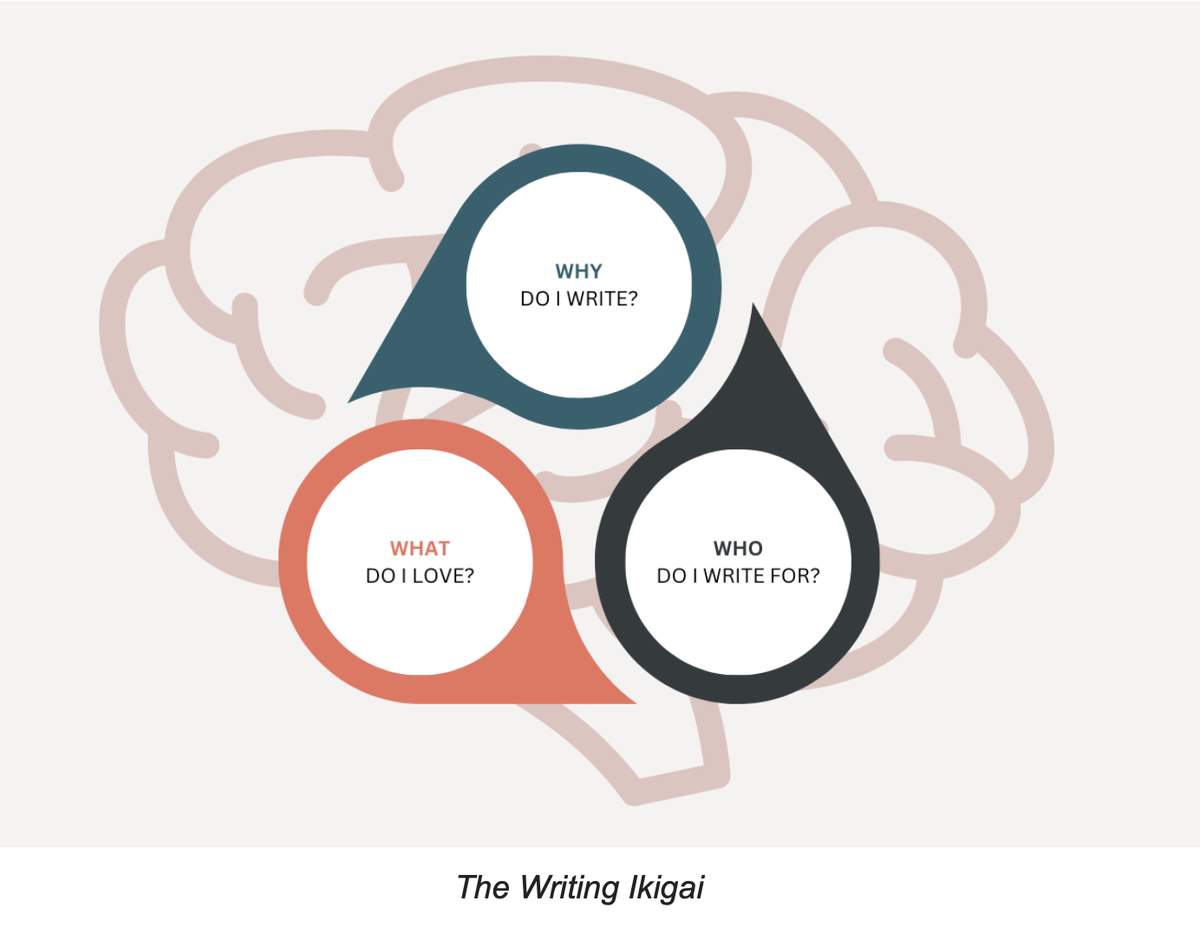

What to write about? How often should you write? In which format? You could spend hours and days overthinking every aspect and not writing a single line. Instead, you can find your “Writing Ikigai” by answering these three powerful questions:

- Why do I write? This question probes your deeper motivations for writing. Is it to express yourself, inform others, entertain, or perhaps to heal? Your ‘why’ will help you get started even if the format and frequency are uncertain. With a clear underlying motive, you can confidently experiment and refine the execution.

- What do I love learning about? The writing process is much more enjoyable, and the words flow more easily when you follow your curiosity. Your ‘what’ could be external (new knowledge, skills, topic of expertise) or internal (your emotions, past experiences, hopes for the future).

- Who am I writing for? Are you writing for yourself, for a specific group of people, or for the world at large? Understanding your ‘who’ will help you tailor your tone and content to the reader — which could simply be your future self.

Just write down these questions — meta, I know — and answer them as truthfully as

possible. Once you’re done, just get started! Maybe it’s a daily journal you keep to yourself,

maybe it’s a quarterly update to your friends and former colleagues, or maybe it’s, like I did, a weekly newsletter.

And you don’t have to stick to just one way of writing. Mix and match it, play, change it up…

In short, have fun! Because writing is thinking, and thinking should be fun.

Twenty-Five Thinking Tools:

Below are twenty-five tools I’ve abstracted from the profession I feel exemplify them best.

Reader’s note:

These are not intended to be full descriptions of every tool that profession uses. That would be silly. Instead, I wanted to pluck one tool that seemed

unique and abstract enough to share with others. These aren’t meant to reduce the full

complexity of a profession down to a single tool, so don’t take it as such.

1. Artist: What if Creativity Were the Priority?

Most other professions are full of constraints upon one’s ideas. They need to be

monetizable, mathematical, under budget and within specifications. Artists operate in a

realm where most of these constraints are reduced, so the bigger question is, “Why is this unique and interesting?”

This, however, is a useful thinking tool to apply to many other concerns. Often the best

companies produce things that look like art. They are driven by uniqueness and creativity

rather than blandly filling out a list of specs.

How would your work change if you made novelty the most significant priority?

How could your goals and projects be different if coolness, interestingness or refinement of an original idea were your priority?

2. Economist: How Do People React to Incentives?

Tyler Cowen, an economist, explains that a key element of economic reasoning is that by changing a system involving people, the people do not stay in place.

Instead, they respond to the new incentives accordingly.

Almost any action you take alters the perceptions of incentives by other people you deal

with.

The economist in you should ask yourself, “if I change this, how will people react?”

3. Engineer: Can I Model This and Calculate?

Engineering, being built off of the hard sciences, has some of the most precise and accurate estimates in any profession. Engineers routinely create things that don’t currently exist and need to work 100% of the time.

The essence of doing this is to create a model of what you’re trying to work with, measure the relevant variables, and know to what degree of error you can expect in those measurements. From there, you can actually know what will happen, instead of just guessing.

4. Entrepreneur: Do a Lot of Things; See What Works

Entrepreneurs often have too little money, resources, support or time. One major tool many use is rapid prototyping.

You make something that just barely works to see if anyone wants it. But in reality, it’s an

abstract thinking tool that applies to a lot more than product R&D.

The essence of this thinking tool is that you go out and try a bunch of things, without waiting around for a perfect answer. It also requires listening carefully for feedback, so you can get hints as to what to do next. Speed and volume make up for making decisions in a noisy environment full of uncertainty.

Sometimes the right way to solve a problem is simply to do a lot of things and see what works!

5. Doctor: What’s the Diagnosis?

Doctors meet patients who have an array of symptoms, some of which they probably aren’t telling you (or can’t).

A good thinking tool from medicine is the idea of using symptoms to deduce a disease, and comparing with base rates to make highly accurate decisions.

While this applies to medicine, there are a lot of places where diagnosis is important. Your car is making a funny noise. Your computer doesn’t work. Your business has stopped making money.

The first thing to do is see what all the possible causes could be. This requires study and

knowledge. Next, you need to rule out as many as possible based on the symptoms you

observe. Finally, of the options that are left, which are rare afflictions and which are fairly

common? Knowing this can help you settle on a most likely diagnosis.

6. Journalist: Just the Facts

Journalists rely on many different thinking tools that allow them to write compelling

stories that report the news fairly and accurately.

One of these thinking tools is fact-checking. Because journalists often need to interview

sources who may be misleading (or even hostile), it’s important to corroborate what was said from independent sources.

How would your life look if you dug around to check the veracity of key pieces of

information you’re depending on to make decisions? Imagine having to report what you know in the New York Times. Would it need to be retracted later?

7. Scientist: Make a Hypothesis and Test It

Scientists discover truths about the world. To do this, they need thinking tools.

A basic thinking tool of science is the controlled experiment.

Keep all the variables the same, except the one you want to test, and see what happens.

Too many people draw inferences from “experiments” that are anything but. Many conflicting variables make drawing conclusions about their experiences much more

difficult. What if you approached your diet like a scientist? Your working routines? Would

you still believe them after?

How many of your beliefs about work and life withstand such scrutiny? Undergo such

testing? Maybe you could benefit from a little more scientific thinking tools in your life.

8. Mathematician: You Don’t Know Until You Can Prove It

The thinking tools of a mathematician depend on having a much higher standard of what

constitutes a proof of something. A mathematician’s statements must be irrefutable or they don’t count.

Mathematical thinking tools help you be more rigorous and spot mistakes that may turn

out to be relevant.

9. Programmer: What’s the Pattern I Can Automate?

Programming encompasses a lot of thinking tools, but the most basic one is the algorithm.

Algorithms are a set of steps that can be defined precisely so that they require no

intelligence to perform each one, yet the net result is a useful product.

A useful application of this is to look at the things you do and see which could be automated, simplified or refactored. Programmers can spot repeated code and try to abstract out the essence of what is redundant into something that can do what you need automatically.

What things do you often repeat in your work that could be automated? What ambiguous process could you convert into a foolproof set of steps?

10. Architect: Envisioning the Future

Architects need to design buildings. To do this, architects need a suite of thinking tools (and software) to take an idea and envision what it will be like, on a large scale, after millions of dollars have been spent. One of those tools is simply making a model.

Making a scaled-down version of the thing you want to create, so you can see how it looks, and then envisioning how it will be on a larger version is difficult, but it often lets you see how reality will be before it’s too late to change it.

11. Salesperson: Understand Their Minds Better than They Do

Selling often gets a bad rap. People think it’s all about trickery and deceit as you try

manipulating someone into buying something they probably shouldn’t.

Salespeople usually work to deeply understand what the customer actually needs and then match them with products and services that fill that void.

A key thinking tool for success in this profession is to infer people’s worries and needs by their (often contradictory behaviour). What language do they use? How do

their actions differ from their stated intentions? What can you infer about this?

What does your spouse really want, rather than what they’re telling you? What about your friends? Your boss?

12. Soldier: Routine and Discipline Prevent Deadly Mistakes

The discipline embodied by military personnel is a very useful thinking tool, even outside of combat situations. Discipline and routine become a safeguard against careless mistakes which could cost lives. By demanding conformity to those protocols, even when there is no danger, there is much less room for slip-ups.

Making your bed every morning may not prevent casualties, but if you can follow that

procedure perfectly, you’ll also be more likely to follow the ones that may save your life. This kind of discipline is also present in another live-endangering field: medicine.

The Checklist Manifesto takes this idea of military routine and applies it to mundane things like hand-washing, which save lives by avoiding infection.

Once you know the best way to do something, do it precisely and exactly, without sloppiness or somebody might get hurt.

13. Chess Master: See The Moves In Your Mind’s Eye

There are plenty of thinking tools that can be mined from the game.

One is the ability to simulate the game in your mind’s eye. A common trick of grandmasters is playing blindfolded games. While this amazes spectators, it actually reinforces a useful practice—being able to see the game in your head so you can calculate future moves your opponent makes.

This is often helpful in other domains outside of chess. Trying to visualize what might

happen and then compare that prediction to reality. This can hone your simulation abilities, so when you’re in a tight spot, you’ll be able to predict what happens next.

14. Designer: The Things You Make Communicate For You

How something is made suggests how to use it. A well-designed door handle suggests push or pull, without needing to say it. A well-designed light switch should already tell you which rooms will be illuminated when you flip it.

What if you designed your speeches so that they automatically caused the audience to shift their thinking where you need them to go? What if you designed your habits so that you automatically applied them? The scope of this thinking tool is really quite broad.

15. Teacher: Can You See What it is Like Not to Know Something Obvious?

How do you create knowledge inside someone else’s mind? How can you give them abilities they didn’t have before?

Most of us take for granted how amazing teaching actually is and our own ability to learn

from it. To be effective, teachers need to have a model of how their pupils' minds see the

world, as well as a game plan for changing it.

To succeed in most professions, you need to be able to make other people see the problems as you do. This involves identifying what knowledge they lack and saying the right things to get them where you are now. While this is an obvious skill for teachers, it also benefits programmers trying to explain their code, doctors trying to articulate the reasons for a medical procedure or a leader who wants employees to follow a vision.

16. Anthropologist: Can You Immerse and Join Another Culture?

Anthropology is the study of cultures. Anthropologists learn about cultures by actually immersing in them.

How could you immerse yourself in groups to which you don’t belong? Groups of different nationalities or languages? Politics or professions? Hobbies, sports, religions or

philosophies? How could you learn how those groups of people function, have them accept you as you live alongside them?

17. Psychologist: Test Your Understanding of Other People

Psychology has different thinking tools embedded in its assumptions about human

nature, as well as in its methods for discovering it.

Cognitive biases, models of attention, morality, preferences, instincts, memory and more.

Interestingly, psychology is also a profession with its own set of tools for discovering

psychology. Like all scientists, this involves creating experiments where you can control all

but the variable you want to study. Unlike other scientists, however, your object of study are human beings, which means you often can’t let them know what you’re trying to adjust.

18. Critic: Can You Build on The Work of Others?

Many critics go beyond telling you which books to read and which movies to watch - experiencing something much more deeply than just a shallow consumer. Second, there’s

the tool of being able to connect that knowledge to a web of other issues and ideas. This

builds on an original creation to add more insight and ideas than were there originally.

19. Philosopher: What are the Unexpected Consequences of an Intuition?

There are a lot of useful thinking tools for dealing with things that can’t be

reduced to numbers.

One powerful tool is being able to see the unexpected consequences of stretching an idea to its limits. This has two benefits. First, it can reveal flaws in the original idea, by reductio ad absurdum. Second, this can help you recognize the fundamental principles behind your vague intuitions of things. By exposing your ideas to stronger, hypothetical critiques, you can see the real mechanisms by which they work.

20. Accountant: Watch the Ratios

There are several useful thinking tools from accounting that allow the diagnosis of

problems that are hidden on the surface. One of these is the idea of ratio analysis. Ratios

are a fraction with a numerator and denominator of two different measurements inside a

business. Leverage ratio, for instance, is the debt the company owes to the equity put in by the owners. Get too high, and there’s a greater risk of default. Price-earnings ratio tells you how expensive stock is based on its profits.

Organizing the data, keeping track of the details and seeing the patterns beneath the surface are all accounting tools you can exploit outside of a spreadsheet.

21. Politician: What Will People Believe?

Politics offers its own set of tools. A major difference between politics and business is that

while both aim to achieve some kind of objective in the world—the former depends highly on the impression of voters. A business can simply work, whereas a politician may do

a great job, and still get kicked out because of bad PR.

Therefore the thinking tools possessed by politicians are about calculating not only the effect of some action, but also on how that action will be perceived. Both by the voting populace, and one’s allies and enemies.

The thinking tools here mean that sometimes the right decision isn’t possible, simply

because other people won’t see it as such, and you don’t have the power to convince them.

22. Novelist: Does Your Story Make Sense?

Many people see stories as the linguistic embodiment of history. We take what actually

happened and weave it into some words so others can see it for themselves.

Stories have characters with fixed traits that make their actions predictable. In real life,

people are more influenced by context. Stories have beginnings, middles and ends. Reality is a continuous stream of events without an arc.

Unfortunately, people understand stories much better than realities. So often, you need to

package up the histories you want to tell people in a way that they can interpret. Who is

involved? When did those things happen? Give information to make it easier for the listener to follow.

While this applies to writing novels or making movies, telling stories is a part of everyone’s

life. From “Why do you want to work at this job,” to, “Where do you see yourself in five

years?” These are all stories, and we need to understand their structures.

23. Actor: The Best Way to Pretend is to Be Real

A popular thinking tool for acting is called method acting. This technique involves trying to

actually feel the emotions of the character you’re portraying, rather than just faking it.

This may seem to be a contradiction: how can you feel something you know is fake?

However, this belies how powerful the imagination is to conjure up situations to create

empathy. Past struggles can stand in place for the struggles of the role you play. Fear,

happiness, confidence and passion all look better when you’re really experiencing it.

Which also suggests a powerful thinking tool, although this one is more affective than

cognitive: changing your emotional state to get the results you want. Feeling insecure, but

know you need confidence? Why can’t you summon that up in yourself as if you’re playing a part? But don’t fake it–feel it.

24. Plumber: Take it Apart and See What’s Broken

Tradespeople don’t get enough credit for having unique problem-solving tools and strategies.

Many academic and intellectual types would never consider a career in plumbing, carpentry or electrical work. Yet those professions often out-earn those with a college degree, and for good reason: they are hard skills which are in-demand.

The essence of plumbing, just like many other trades, is to get your hands dirty and take

something apart to see what’s broken. To do this, you need a model of what’s in there—

otherwise you might get water spilling everywhere or a dangerous shock. But you also need to take things apart to understand them.

How many of us avoid understanding things because we’re afraid to get our hands dirty? We don’t want to risk breaking something, so we never really understand how it works?

25. Hacker: What’s Really Going on Underneath?

Hacking is one of the most commonly misunderstood skills. Television shows portray it as a kind of computer magic, with flying cubes and firewall health bars which go down to zero.

In practice, however, hacking is mostly about understanding that there is often a more

complicated layer of instructions which a simpler layer is built on top.

This thinking tool works for computers, but also other areas of life. Remember: everything

you see is usually a simplification of a deeper reality. Which can mean that the underlying

system may be broken in a way you wouldn’t naively expect.

Final Thoughts on Thinking Tools

These are just summaries of a key tool from different professions. In reality, however, there

are dozens, if not hundreds of thinking tools for each domain of skill. Not just professions, but hobbies, subjects and general life skills also develop thinking tools.

The problem is that people often have a difficult time recognizing the skill and abstracting it away from where it was generated. This is a problem of far transfer, and it’s not easy to

resolve.

However, if you can state what the pattern is, you can start to see how you could apply it

elsewhere. Most of these tools won’t work best in domains far outside their starting zones. A novelist trying to use storytelling to diagnose medical problems will be in big trouble. But often, we get so stuck using our favourite tools that we don’t even consider which ones could apply. Creative solutions require divergent thinking, causing us to think of one tool when we need others.