Teaching & Learning Page:

Web Pages:

Make it yourself - makeityourself.org

Expose email scams instantly - https://snitcher.space

https://thevaluesbridge.com

Historical Tech -

https://www.historicaltechtree.com

https://bdayrecap.com

Techie Tips:

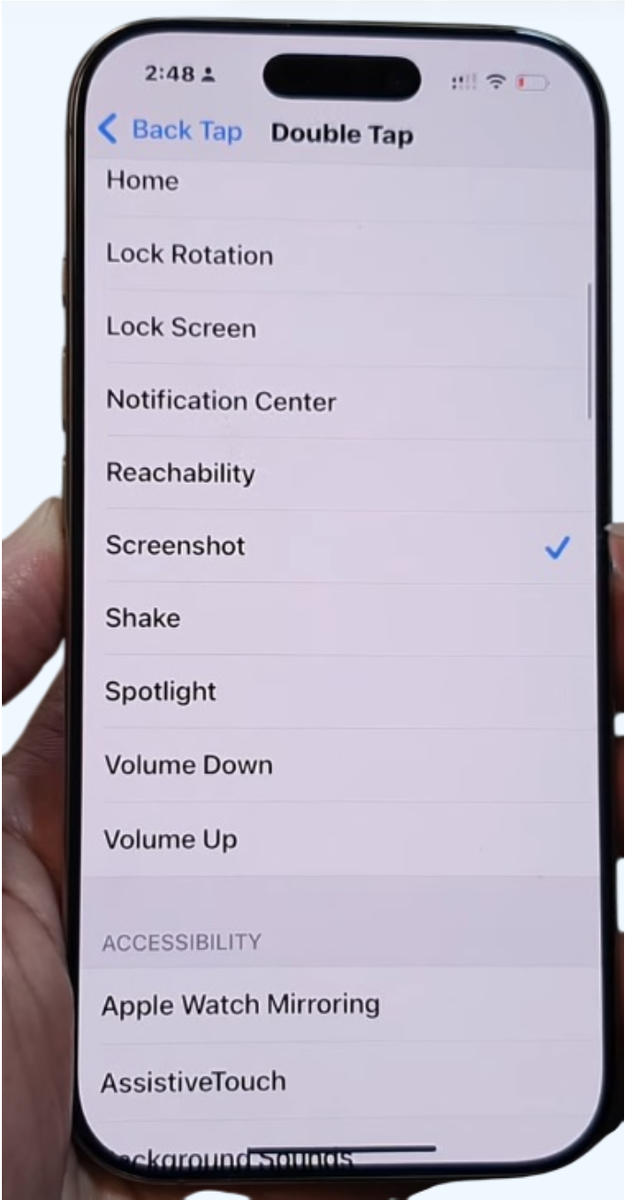

This one is overlooked mostly, but it seemed pretty cool when I first discovered it. Imagine

tapping the back of your iPhone to take a screenshot, open the camera, or even launch a specific app.

Here is how to set it up:

Go to Settings > Accessibility > Touch > Back Tap

Choose Double Tap or Triple Tap

Assign it to common actions like:

Take Screenshot

Lock Screen

Open Control Centre

Launch Shortcuts (you can even use this for automation)

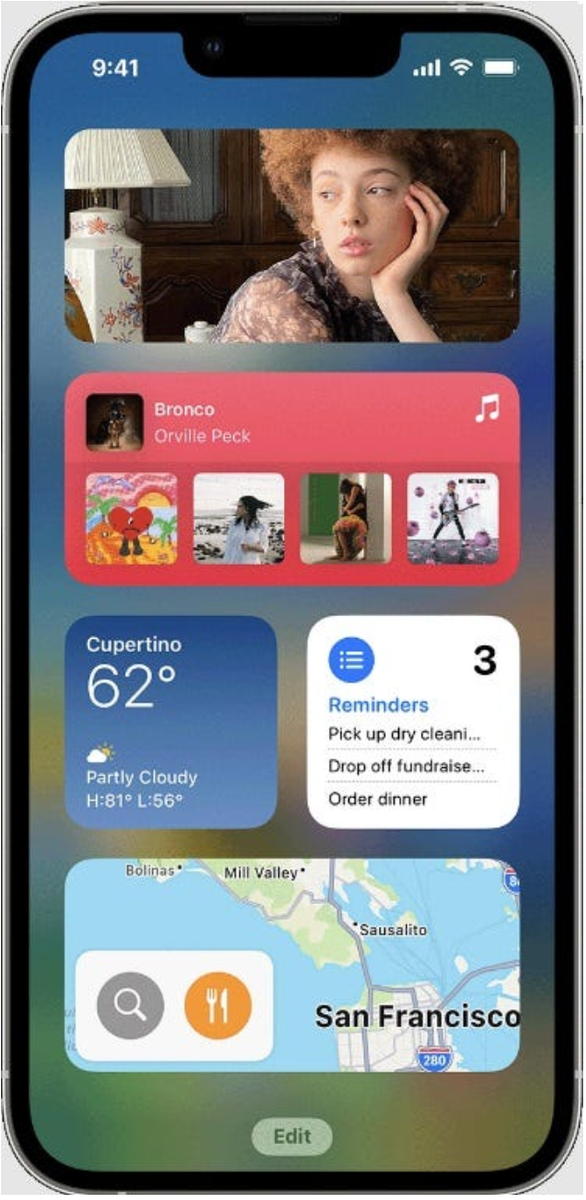

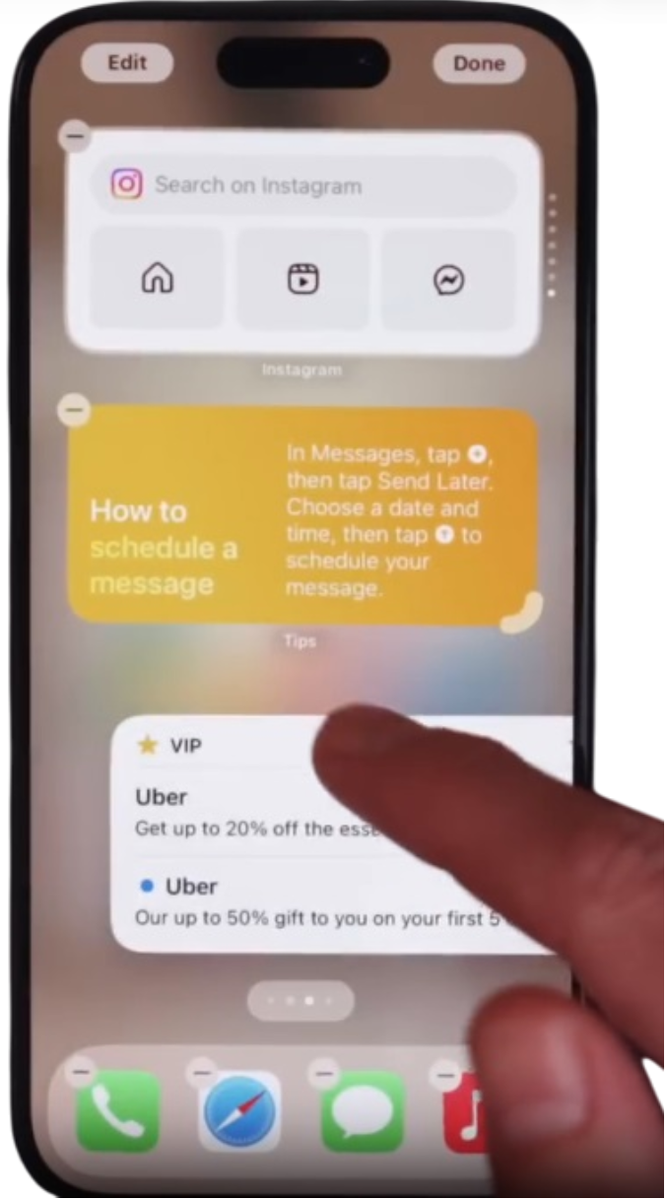

Tidy Up Widgets with Smart Stacks

We love widgets, weather, calendar, music controls, you name it, but your home screen starts looking like a chaotic billboard (over time).

The solution - a way to stack or organise widgets, like folders for apps.

And Smart Stacks is the answer.

You can create one by:

Long-pressing on your home screen until you enter edit mode.

Tapping the in the upper-left corner.

Selecting “” from the widget list.

Once added, you can swipe through widgets vertically, and if you long-press the stack

and tap “Edit Stack”, you can:

Reorder them.

Remove unwanted ones.

Add new widgets that support stacking.

And here is a hidden gem:

You can even create a stack by dragging one widget on top of another. It is fast, intuitive, and exactly how you would make a folder with apps.

For example, a “Productivity Stack” with Reminders, Calendar, and Notes widgets and your home screen will look so much cleaner.

Sketches:

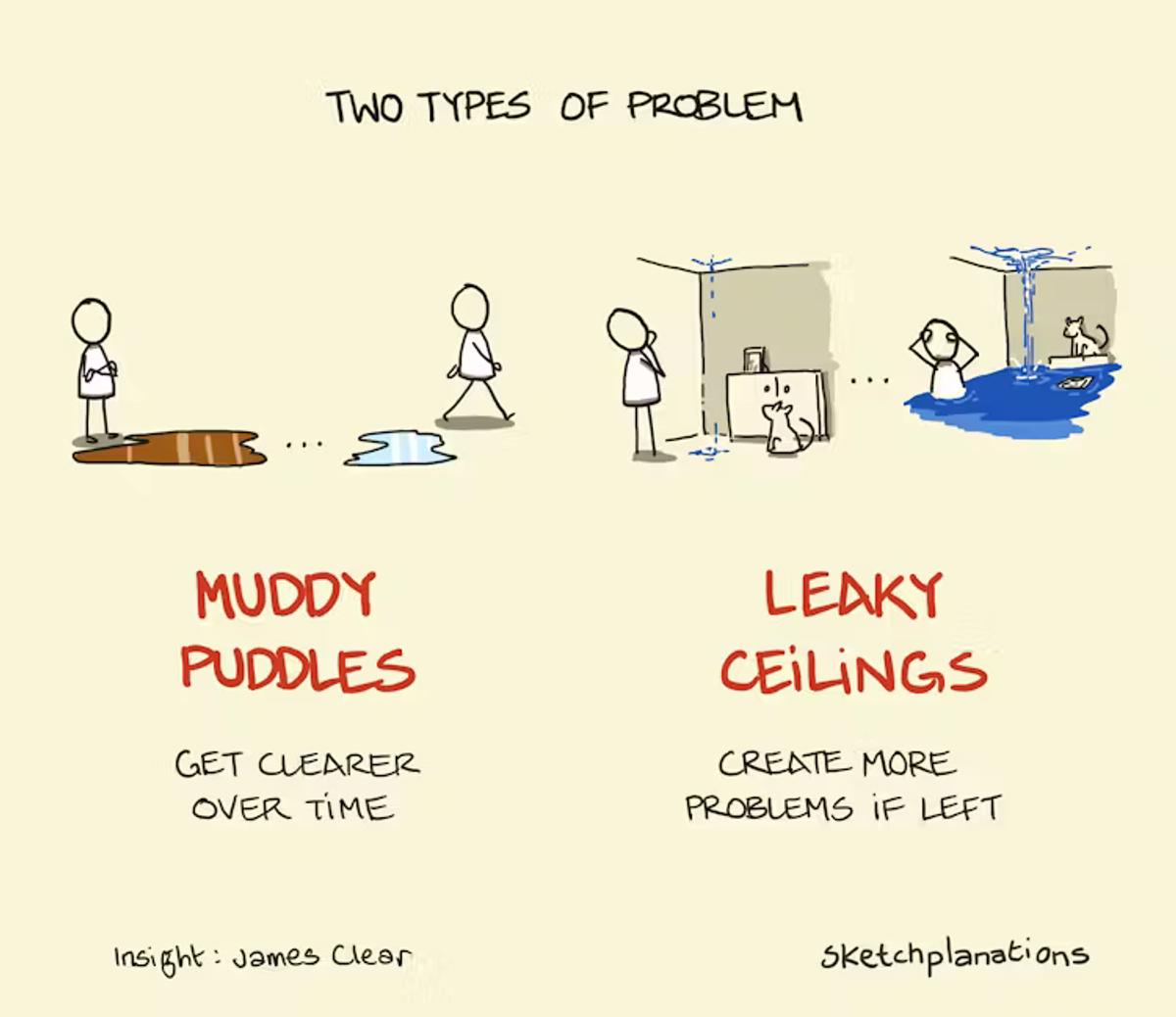

What type of problem are you dealing with? James Clear shared a technique of splitting problems into two types: muddy puddles or leaky ceilings.

A muddy puddle problem is one where leaving it alone can help to make it clearer.

A leaky ceiling problem is one where leaving it alone causes more problems.

Leaky ceilings need to be resolved soon. Muddy puddles can be left until they are clearer.

Here's James Clear explaining it in his own words :

"I split problems into two groups: muddy puddles and leaky ceilings.

Some problems are like muddy puddles. The way to clear a muddy puddle is to leave it alone. The more you mess with it, the muddier it becomes. Many of the problems I dream up when I'm overthinking, worrying, or ruminating fall into this category. Is life really falling apart or am I just in a sour mood? Is this as hard as I'm making it, or do I just need to go work out? Drink some water. Go for a walk. Get some sleep. Go do something else and give the puddle time to turn clear.

Other problems are like a leaky ceiling. Ignore a small leak and it will always widen. Relationship tension that goes unaddressed. Overspending that becomes a habit. One missed workout drifting into months of inactivity. Some problems multiply when left unattended. You need to intervene now.

Are you dealing with a leak or a puddle?"

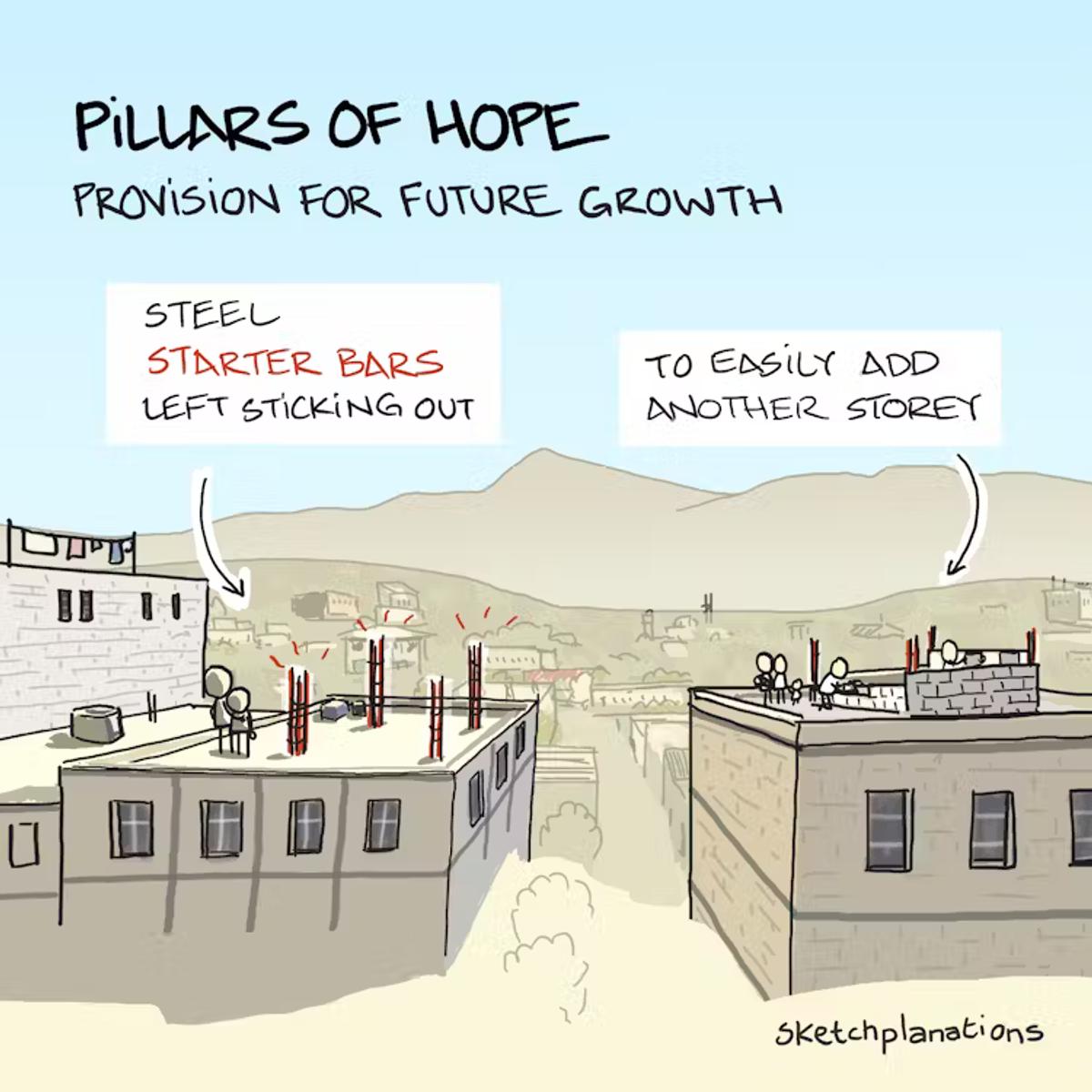

"Pillars of Hope" is a tongue-in-cheek name for steel starter bars, also known as starter rods or rebar extensions, that protrude from the roofs of houses after construction. Leaving starter bars sticking out is a pragmatic approach, saving time and money when adding the next floor, as the structure is already partially prepared for the expansion. The "hope" in the name reflects the anticipation and optimism of adding to their homes in the future when the family grows or their financial situation improves.

Growing up in the UK, I never encountered the practice of leaving exposed starter bars on houses. However, while travelling through Central America and Asia, I was surprised to see these exposed rods in many towns and cities. At first, I couldn't understand why so many buildings seemed unfinished, making the skyline somewhat messy. Only when someone explained their purpose to me did it make complete sense.

Steel bars in concrete combine the tensile strength of steel with the compressive strength of concrete, creating a remarkably effective and widely used building method. The starter bars embedded in and protruding from the existing structure provide a strong and stable connection between a new addition and the existing building. The bars transfer loads and anchor the two together.

Pillars of Hope are a conspicuous example of futureproofing. Other examples in buildings are electrics or plumbing, where you might leave capped-off pipes or electrical connection points in anticipation of future work. Laptops and desktop computers with empty expansion slots also use this approach, as does a first edition of software that includes an update manager.

In software and agile development, I like the sentiment from the book Rework : "A kick-butt half is better than a half-butt whole." Have no parts of your product not yet working or "under construction" that are visible to users. Don't leave any visible "starter bars" sticking out of your product. And try not to solve problems that you don't yet have. While it might seem worth adding something now to make a future feature easier to build, it's a tricky balance. So often, you choose to do something else in the future instead and are left with some software pillars of hope sprinkled throughout your code—technical debt you may have to pay off later.

While my first reaction to steel rods sticking out of houses seemingly willy-nilly was that it was chaotic and messy, when I think about them as Pillars of Hope, I now find it kind of beautiful—looking out over a skyline and seeing the aspirations and future development of families, homes and a city sketched out on the rooftops.

Edit:

Several people told me that leaving starter bars sticking out of a roof makes the building 'unfinished' and not liable to tax on the work. While this is repeated in many places, I'm not 100% sure of the truth.

Ash's Note:

I was told this is the case in Greece when I was there in 2018. This was an explanation as to why local and national governments were struggling because they could not collect land taxes on unfinished properties.

Article:

Is AI Making Us Dumb ? - A Deep Dive into the Cognitive Cost of Convenience

The human brain has always adapted remarkably well to technology. But what happens when the technology starts doing the thinking for us?

Let’s begin with something simple:

Google Maps. Most of us use it daily. Yet a 2020 study revealed a hidden cost. Despite the app’s utility, frequent use of GPS systems was found to weaken users’ spatial memory (Adamopoulou & Moussiades, 2020). Even more interestingly, users didn’t believe their sense of direction had declined, though the data said otherwise. Convenience, it seems, comes at a cognitive price.

That’s not even AI — that’s just an app. So what happens when the tool is AI?

Around the same time, Professor David Rafo noticed something curious in his students’ writing. Prior to the pandemic, their assessments were weak and lacked structure.

Suddenly, during lockdown, their writing improved drastically. Too drastically. Suspecting AI, Rafo asked his students directly. His hunch was correct. “I realised it was the tools that improved their writing, not their writing skills,” he said (Portland State University, n.d.).

Rafo wasn’t anti-AI. He acknowledged the benefits, noting how AI helps with everything from drafting content to problem-solving. But he warned, “Our cognitive abilities are like muscles. They need regular use to stay strong and vibrant.” The real concern, he explained, is that resisting the ease AI offers takes extraordinary discipline.

This is where the concept of cognitive atrophy comes in — the gradual weakening of our mental faculties due to over-reliance on external tools (Dergaa et al., 2023).

Alzheimer’s researcher Dr. Anne McKee emphasised the importance of mental activity to prevent cognitive decline. Staying mentally active builds resilience against diseases like Alzheimer’s. High cognitive reserve can offset even visible brain damage (Diary of a CEO, 2023).

Yet, we find ourselves offloading that mental effort more and more. One systematic review examined the over-reliance on AI dialogue systems in academic settings. The findings were clear: excessive dependence erodes critical thinking, decision-making, and analytical reasoning (Zhai, Wibowo, & Li, 2023). While AI can streamline workflows, it also introduces ethical concerns — misinformation, algorithmic bias, plagiarism, privacy breaches, and opacity (Dergaa et al., 2023).

This is a well-worn path in tech. Studies have shown how calculators impacted basic math skills, and autocorrect diminished spelling and punctuation accuracy. But now we’re in a new domain. Tools like ChatGPT, Grok, and LLaMA don’t just support us — they do the thinking (Bai, Liu, & Su, 2023).

AI is already absorbing tasks like data entry, customer service, or bookkeeping. And a worrying trend is emerging: cognitive offloading. This refers to using external tools to reduce the effort needed for thinking or problem-solving. In a recent Forbes study, frequent AI users were more likely to rely on tech for decisions, leading to reduced ability to evaluate or think critically (Daniel, 2025).

This cognitive offloading extends to serious domains like law enforcement. In 2023, Detroit police used an AI facial recognition tool called DataWorks Plus to solve a robbery case. The AI matched low-quality footage to a 2015 mugshot. The woman — Porsche Woodruff — was eight months pregnant and nowhere near the crime scene. She was still arrested (New York Times, 2023). The charges were later dropped, but the damage was done. This wasn’t an isolated case. There are currently multiple lawsuits against the Detroit Police Department for similar incidents — all stemming from AI dependence.

Why did this happen? Because people trusted the AI. Just like with GPS. The errors are hard to detect when the tool becomes part of everyday life. And when you look online, you see the signs. On platforms like X/Twitter, users now routinely ask AI bots such as Grok to explain even simple tweets (Mitchell, 2024). They’ve outsourced their curiosity.

While certain users may find value in utilising AI on social media to save time, the habitual delegation of even the simplest interpretive tasks to AI systems warrants deeper concern. This trend reveals a broader, often subconscious behavioral shift: a collective surrender to algorithmic decision-making. On platforms such as Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, and YouTube — often the gateways through which individuals access content — algorithms largely dictate what users see. The outcome is a subtle erosion of personal agency.

Alec Watson, from the channel Technology Connections, terms this phenomenon “algorithmic complacency.” He notes that increasingly, users prefer letting computer programs decide their digital experience, even when alternative pathways are available. In reflecting on this shift, Watson recalls a time when internet engagement was deliberate — users manually bookmarked pages and curated their online experiences. In contrast, today’s digital ecosystem fosters passive consumption, driven by machine-selected content.

For individuals entering adulthood in the 2020s, there is a notable trend: algorithms are trusted more than human judgment. This trust has consequences. Students who used AI during the pandemic to cut corners in school are now employees relying on AI to write emails, create reports, and even make decisions. Surveys show that 90% of Gen Z employees use two or more AI tools weekly (ColdFusion, 2024). Some say it’s simply working smarter. Others see it as a slow erosion of mental muscle.

We’ve now transitioned from the Information Age into the Knowledge Age — one shaped not by facts alone, but by AI-generated interpretations of those facts. But there’s a problem: much of that knowledge is flawed. Google’s AI Overviews once called Obama the first Muslim president and claimed snakes were mammals (BBC, 2024).

And it gets worse. Oxford researchers discovered a phenomenon called model collapse. When AI models are fed AI-generated content repeatedly, the quality degrades rapidly (Forbes Australia, 2024). After just nine iterations, the output becomes gibberish. A separate study by Amazon found that 60% of today’s internet content may already be AI-generated or AI-translated.

We're in the midst of the AI Slop, where the internet feeds itself.

This leads to the theory of the “dead internet,” where bots and AI generate the majority of content.

And yet, there’s hope. AI is still a tool. It’s not inherently bad. We’ve faced this before. When Dan Bricklin and Bob Frankston created VisiCalc — the first spreadsheet app — in 1979, many feared it would make accountants obsolete. But it didn’t. It enhanced their productivity (Wordyard, 2003).

The same is true for AI today. Use it as a companion — not a replacement for thought. Take its answers with a grain of salt. As Professor Thomas Diettrich put it: “Large language models are statistical models of knowledge bases. They’re not knowledge bases themselves.”

And therein lies the danger. When the model never refuses, it invites trust — even when it shouldn’t. That’s why awareness is key.

We must approach AI in the same way. Let it help, but don’t let it lead. Because no matter how advanced these systems become, nothing can replace the uniquely human ability to think, reason, and create.

As René Descartes once said: Cogito, ergo sum.

I think, therefore I am.

That’s what makes us human.

APA References:

Adamopoulou, E., & Moussiades, L. (2020). Chatbots: History, technology, and applications. Machine Learning with Applications, 2, 100006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mlwa.2020.100006

Bai, L., Liu, X., & Su, J. (2023). ChatGPT: The cognitive effects on learning and memory. Brain, 1, e30. https://doi.org/10.1002/brx2.30

BBC. (2024). AI search results are full of errors. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/ckg9k5dv1zdo

ColdFusion. (2024). Is AI making us dumber? [YouTube video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aOW_HslF5ko

Daniel, L. (2025, January 19). New study says AI is making us stupid — but does it have to? Forbes.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/larsdaniel/2025/01/19/new-study-says-ai-is-making-us-stupid/

Dergaa, I., Ben Saad, H., Glenn, J. M., Amamou, B., Ben Aissa, M., Guelmami, N., Fekih-Romdhane, F., & Chamari, K. (2023). From tools to threats: A reflection on the impact of artificial-intelligence chatbots on cognitive health.

Forbes Australia. (2024). Is AI quietly killing itself — and the internet? https://www.forbes.com.au/news/innovation/is-ai-quietly-killing-itself-and-the-internet/

Mitchell, M. [@MelMitchell1]. (2024). AI replies on X show worrying overreliance [Tweet]. https://x.com/MelMitchell1/status/1793749621690474696

New York Times. (2023, August 6). A wrongful arrest shows the dangers of facial recognition.

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/06/business/facial-recognition-false-arrest.html

Portland State University. (n.d.). Professor David Raffo.

https://www.pdx.edu/profile/david-raffo

Wordyard. (2003, April 9). VisiCalc memories. https://www.wordyard.com/2003/04/09/visicalc-memories/

Zhai, C., Wibowo, S., & Li, L. D. (2023). The effects of over-reliance on AI dialogue systems on students’ cognitive abilities: A systematic review.

Book Recommendation:

Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance

Paperback – August 21, 201

by Angela Duckworth (Author)

4.6 4.6 out of 5 stars (19,978)

4.1 on Goodreads, 136,681 ratings

Goodreads Choice Award nominee

Angela Duckworth shows anyone striving to succeed that the secret to outstanding achievement is not talent, but a special blend of passion and persistence she calls “grit.”

The daughter of a scientist who frequently noted her lack of “genius,” Angela Duckworth is now a celebrated researcher and professor. It was her early eye-opening stints in teaching, business consulting, and neuroscience that led to her hypothesis about what really drives success: not genius, but a unique combination of passion and long-term perseverance.

In Grit, she takes us into the field to visit cadets struggling through their first days at West Point, teachers working in some of the toughest schools, and young finalists in the National Spelling Bee.

She also mines fascinating insights from history and shows what can be gleaned from modern experiments in peak performance. Finally, she shares what she’s learned from interviewing dozens of high achievers—from JP Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon to New Yorker cartoon editor Bob Mankoff to Seattle Seahawks Coach Pete Carroll.

“Duckworth’s ideas about the cultivation of tenacity have clearly changed some lives for the better” (The New York Times Book Review).

Among Grit’s most valuable insights:

- Any effort you make ultimately counts twice toward your goal

- Grit can be learned, regardless of IQ or circumstances

- When it comes to child-rearing, neither a warm embrace nor high standards will work by themselves

- How to trigger lifelong interest

- The magic of the Hard Thing Rule

Winningly personal, insightful, and even life-changing, Grit is a book about what goes through your head when you fall down, and how that—not talent or luck—makes all the difference. This is “a fascinating tour of the psychological research on success” (The Wall Street Journal).