Teachers' Page:

We start each week with a Monday Morning Meeting for staff. It's a time for information sharing, celebrating staff and children's achievements, laughter, building and strengthening the kaupapa foundations for our school, and a few tips on teaching, techie skills and even life. This page will be the place teachers can come back to if they want to revisit anything we covered in our Monday Morning Meetings.

It's really a page for teachers, but if you find anything worthwhile here for yourself, great.

New Study Reveals The Single Most Important Factor for Learning Rate:

by Scott Young

Recently, I wrote a defense of psychologist John Carroll’s claim that what separated stronger and weaker students wasn’t a fundamental difference in learning potential, but a difference in learning rate. Some people learn faster and others more slowly, but provided the right environment, essentially anyone can learn anything.

In arguing that, I primarily wanted to dispute the common belief that talent sets hard limits on the skill and knowledge you can eventually develop. Not everyone could become a doctor, physicist or artist, the reasoning goes, because some people will hit a limit on how much they can learn.

However, in arguing that the primary difference between students was learning rate, I may have also been committing an error!

A recent paper I encountered suggests that the rate of learning among students doesn’t actually differ all that much. Instead, what differs mostly between students is their prior knowledge.[1]

“An Astonishing Regularity”

The paper, “An astonishing regularity in student learning rate,” was authored by Kenneth Koedinger and colleagues.They observed over 6000 students engaged in online courses in math, science, and language learning, ranging from elementary school to college.

By delivering the material through online courses, the authors could carefully track which lessons, quizzes and tests the students took.

The authors then broke down what students were learning into knowledge components and created a model that defined the individual factors responsible for learning each topic.

The model breaks what students learn into prior knowledge inferred from their performance on test items before instruction begins, and a measure of new learning. The actual details of the model are a little technical, so if you’re interested, you can read the paper or see this footnote.[2]

Immediately, the authors observed that students enter classes with substantial differences in prior knowledge. The average pre-instruction performance was 65%, with more poorly performing students at 55% and better performing students at 75%.

This difference in prior knowledge translated to differing volumes of practice needed to achieve mastery, which the authors defined as an 80% probability of success. Strong students needed roughly 4 opportunities to master a given knowledge component, whereas weaker students required more than 13. A dramatic difference!

However, the rate of learning between strong and weaker students was surprisingly uniform. Both groups improved at the same rate — achieving roughly a 2.5% increase in accuracy per learning opportunity. It was simply that the better students started with more knowledge, so they didn’t have as far to go to reach mastery.

While the authors did find a slight divergence in learning rates, it was dwarfed by the impact of prior knowledge. According to this model, students required an average of seven practice exposures per knowledge element to achieve mastery. When the level of prior knowledge was equalized between “fast” and “slow” learners, the “slow” learners only needed one additional practice opportunity to equal the rate of the “fast” learners.

If All Learners are Equally Fast, Why Do Some Have So Much More Knowledge?

This result surprised me, but it wasn’t the first time I have encountered this claim. Graham Nuthall made a similar observation in his extensive research in New Zealand classrooms, finding that students required roughly five opportunities to learn a given piece of knowledge, and the rate did not vary between students — although prior knowledge did.

Still, it raises an obvious question: if learning rates are equal, why do some students enter classes with so much more prior knowledge? Some possibilities:

- Some students have backgrounds outside of school that expose them to greater knowledge. One of the famous results of early vocabulary learning is that children from affluent backgrounds are exposed to far more words than those from poor and working-class socioeconomic backgrounds.

- Some students might be more diligent, curious and attentive. The authors note that their learning model fits the data much better when you count learning opportunities, not calendar time elapsed. Thus, if a student gets far more learning opportunities within the same class (by paying attention to lectures, doing the homework, etc.) than a classmate, they will have dramatically different overall learning rates, even if their learning rate per opportunity is the same.

- Perhaps learning rate is uniform only in high-quality learning environments. A common finding throughout educational research is that lower aptitude students benefit from more guidance, explicit instruction and increased support. It might be the case that learning rates diverge for less learner-friendly environments than the one studied here.

Another possibility is that small differences in learning rates tend to compound over time. Those who learn faster (or were given more favourable early learning environments) might seek out more learning and practice opportunities, resulting in bigger and bigger differences accumulated over time.

In reading research, Keith Stanovich was one of the first to propose this Matthew effect for reading ability. Those with a little bit of extra ability in reading find it easier and more enjoyable to read, get more practice, and further entrench their ability.

Still, a countervailing piece of evidence to this view is that the heritability of academic ability tends to increase as we age. Teenagers’ genes are more predictive of their intelligence than younger children’s genes are. That kind of pattern doesn’t make sense if we believe large gaps in academic ability are simply due to positive feedback loops — that would suggest those who, through random factors, were above their predicted potential would continue to entrench their advantage rather than regress to the mean.

Those remaining questions aside, I found Koedinger’s paper fascinating, both for providing a provocative hypothesis regarding learning and their effort to systematically model the knowledge components involved in learning, offering a finer-grained analysis than many experiments that rely only on a few tests.

Web Pages:

www.theconsciouskid.org/book-lists

Techie Tips:

Mac Settings to Change to Enhance Your Experience:

Make Finder usable

In its default configuration, Finder is not that much useful. That’s why the first thing we do on a new Mac is customize it to improve it. When you open the Finder app, you will see that it opens the Recents folder menu. For me, this is more or less useless. So, we changed it to the Downloads folder.

To customize this behavior, use the Finder menu to open settings, and under the New Finder windows show setting, select the folder you want to open. We have set it to Downloads as that’s the folder we use the most. You can set it to any folder you want.

While in the Finder settings, click on the Sidebar tab. You can select which folders you want to see in Finder’s sidebar. We disabled the Recents, Picture, and Movies folders and removed the Recent Tags section as we don’t use them.

The final thing we customize in Finder is the toolbar at the top. To customize the toolbar, right-click or control-click on the toolbar and choose the Customize toolbar… option.

We added the AirDrop action to the toolbar as it allows us to send files via AirDrop with just a click. All you need to do is select the file you want to send and click the AirDrop icon to open the AirDrop menu.

Customize display settingsThe next thing we change is the display settings on the Mac. To open the Display settings on your Mac, click on the Menu in the top-right corner and choose the System Settings option. System Settings is where you can modify all the OS-level settings, and we will use it a lot in this guide.

In the System Settings window, scroll down the left sidebar and click to select the Displays settings. Here, the first thing we do is to pick the More Space display scaling option. It scales the display and reduces the size of UI elements, giving you more space to work with. If you have poor eyesight, this is where you can increase the text size.

Another thing we disable here is the Automatic Brightness setting, as it’s quite frustrating. We enjoy watching video content with lights off, and macOS automatically reduces the brightness when it senses low ambient lighting, so we have to keep increasing the brightness every few minutes. To stop this madness, I keep the automatic brightness turned off.

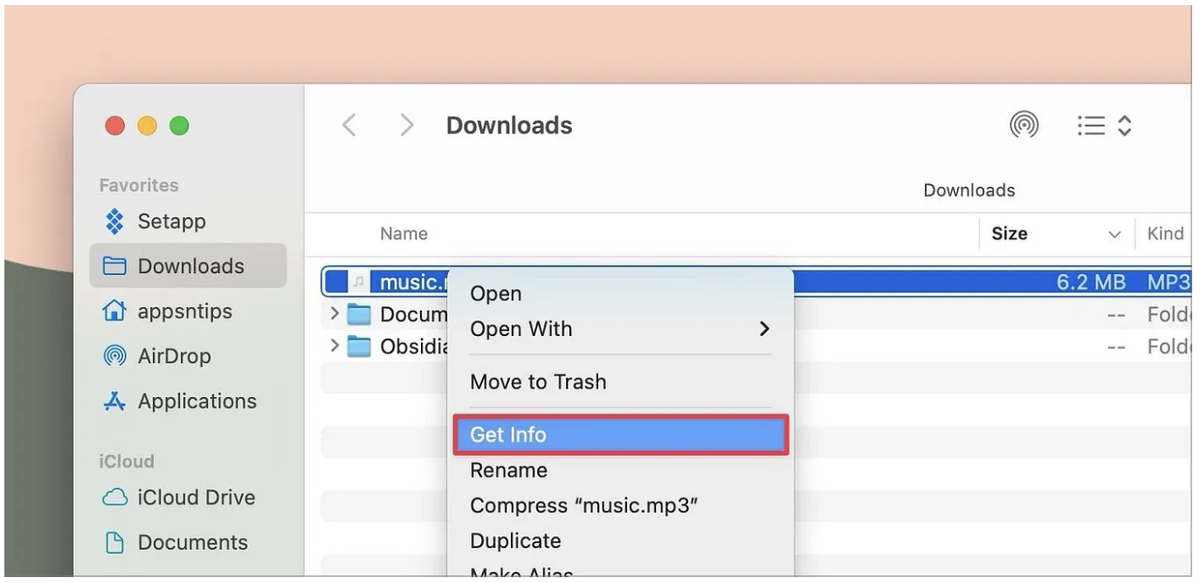

Change the default opening app for filesThe next thing to change in macOS is the default opening apps for files. While you can do this for any file type, the one you should definitely change is for music files. By default, macOS opens any audio file in the Music app, and the experience is not good.

If you use a third-party music app, we recommend setting it as the default app. To set a default app for a file, select the file and hit the ⌘i keyboard shortcut. You can also right-click on the file and choose the Get Info option.

Now look for the Open with option and use the dropdown menu to choose the app.

Finally, click the Change All… button to change the default app. You can do this for all file types. Remember the changes effect not based on file type but file extension.

For example, if you have audio files in MP3 and MP4 formats, you will have to change the default app for both these formats separately.

Fix Hot CornersHot Corners is one of our favorite software features of macOS, but it’s broken in its default configuration. Even if you haven’t used this feature before, you have experienced its irritating behavior when you move the cursor to the bottom-right corner of the screen. By default, it opens a Quick Note, which is useful on the iPhone but almost useless on the Mac.

To fix this mess, we will not only change what happens when you move your cursor to the corners but also ensure that you don’t trigger the action accidentally. Again, open the System Settings app and this time go to the Desktop & Dock settings. Now scroll down the right sidebar and click the Hot Corners… button.

As you can see, you can see separate actions for each of the corners of the display. I only use the bottom left and right corner and set them to Put Display to Sleep and Lock Screen actions. To ensure that you don’t accidentally trigger these actions, hold down a modifier key before choosing the action.

As you can see, when I hold down the ⌥ key, its symbol appears next to the action. You can also choose the ⌘, ⇧, or ⌃ keys if you want. Now, when you want to trigger hot corners, you need to hold the modifier key. This ensures that you don’t accidentally activate hot corners on your Mac.

Create a custom folder iconWe love that macOS allows us to change icons for folders and apps. While we don’t always change the app icon, we love this feature to change folder icons to make them more identifiable.

To change a folder icon, select it and hit the ⌘i keyboard shortcut to open the info panel. Alternatively, right-click on the folder and choose the Get Info option.

To change the folder icon, drag and drop the icon you want to use where you see the folder icon.

Disable click wallpaper to display desktopThe one thing that has irritated us the most after updating to the latest macOS Sonoma update is the click-to-display desktop feature. In macOS Sonoma, when you click on an empty area, it displaces all the app windows to show you the desktop.

The feature is quite irritating, and we recommend turning it off as soon as possible. To turn off this feature, go to System Settings and open the Desktop & Dock settings.

To Ponder:

Why Facts Don’t Change Our Minds:

written by James Clear - author of Atomic Habits

The economist J.K. Galbraith once wrote, “Faced with a choice between changing one’s mind and proving there is no need to do so, almost everyone gets busy with the proof.”

Leo Tolstoy was even bolder: “The most difficult subjects can be explained to the most slow-witted man if he has not formed any idea of them already; but the simplest thing cannot be made clear to the most intelligent man if he is firmly persuaded that he knows already, without a shadow of doubt, what is laid before him.”

What’s going on here? Why don’t facts change our minds? And why would someone continue to believe a false or inaccurate idea anyway? How do such behaviours serve us?

The Logic of False Beliefs

Humans need a reasonably accurate view of the world in order to survive. If your model of reality is wildly different from the actual world, then you struggle to take effective actions each day.

However, truth and accuracy are not the only things that matter to the human mind. Humans also seem to have a deep desire to belong.

In Atomic Habits, I wrote, “Humans are herd animals. We want to fit in, to bond with others, and to earn the respect and approval of our peers. Such inclinations are essential to our survival. For most of our evolutionary history, our ancestors lived in tribes. Becoming separated from the tribe—or worse, being cast out—was a death sentence.”

Understanding the truth of a situation is important, but so is remaining part of a tribe. While these two desires often work well together, they occasionally come into conflict.

In many circumstances, social connection is actually more helpful to your daily life than understanding the truth of a particular fact or idea. The Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker put it this way, “People are embraced or condemned according to their beliefs, so one function of the mind may be to hold beliefs that bring the belief-holder the greatest number of allies, protectors, or disciples, rather than beliefs that are most likely to be true.”

We don’t always believe things because they are correct. Sometimes we believe things because they make us look good to the people we care about.

I thought Kevin Simler put it well when he wrote, “If a brain anticipates that it will be rewarded for adopting a particular belief, it’s perfectly happy to do so, and doesn’t much care where the reward comes from — whether it’s pragmatic (better outcomes resulting from better decisions), social (better treatment from one’s peers), or some mix of the two.”

False beliefs can be useful in a social sense even if they are not useful in a factual sense. For lack of a better phrase, we might call this approach “factually false, but socially accurate.” When we have to choose between the two, people often select friends and family over facts.

This insight not only explains why we might hold our tongue at a dinner party or look the other way when our parents say something offensive but also reveals a better way to change the minds of others.

Facts Don’t Change Our Minds. Friendship Does.

Convincing someone to change their mind is really the process of convincing them to change their tribe. If they abandon their beliefs, they run the risk of losing social ties. You can’t expect someone to change their mind if you take away their community too. You have to give them somewhere to go. Nobody wants their worldview torn apart if loneliness is the outcome.

The way to change people’s minds is to become friends with them, to integrate them into your tribe, to bring them into your circle. Now, they can change their beliefs without the risk of being abandoned socially.

The British philosopher Alain de Botton suggests that we simply share meals with those who disagree with us:

“Sitting down at a table with a group of strangers has the incomparable and odd benefit of making it a little more difficult to hate them with impunity. Prejudice and ethnic strife feed off abstraction. However, the proximity required by a meal – something about handing dishes around, unfurling napkins at the same moment, even asking a stranger to pass the salt – disrupts our ability to cling to the belief that the outsiders who wear unusual clothes and speak in distinctive accents deserve to be sent home or assaulted. For all the large-scale political solutions which have been proposed to solve ethnic conflict, there are few more effective ways to promote tolerance between suspicious neighbours than to force them to eat supper together.”

Perhaps it is not difference, but distance that breeds tribalism and hostility. As proximity increases, so does understanding. I am reminded of Abraham Lincoln’s quote, “I don’t like that man. I must get to know him better.”

The Spectrum of Beliefs

Years ago, Ben Casnocha mentioned an idea to me that I haven’t been able to shake: The people who are most likely to change our minds are the ones we agree with on 98 percent of topics.

If someone you know, like, and trust believes a radical idea, you are more likely to give it merit, weight, or consideration. You already agree with them in most areas of life. Maybe you should change your mind on this one too. But if someone wildly different than you proposes the same radical idea, well, it’s easy to dismiss them as a crackpot.

One way to visualize this distinction is by mapping beliefs on a spectrum. If you divide this spectrum into 10 units and you find yourself at Position 7, then there is little sense in trying to convince someone at Position 1. The gap is too wide. When you’re at Position 7, your time is better spent connecting with people who are at Positions 6 and 8, gradually pulling them in your direction.

The most heated arguments often occur between people on opposite ends of the spectrum, but the most frequent learning occurs from people who are nearby. The closer you are to someone, the more likely it becomes that the one or two beliefs you don’t share will bleed over into your own mind and shape your thinking. The further away an idea is from your current position, the more likely you are to reject it outright.

When it comes to changing people’s minds, it is very difficult to jump from one side to another. You can’t jump down the spectrum. You have to slide down it.

Any idea that is sufficiently different from your current worldview will feel threatening. And the best place to ponder a threatening idea is in a non-threatening environment. As a result, books are often a better vehicle for transforming beliefs than conversations or debates.

In conversation, people have to carefully consider their status and appearance. They want to save face and avoid looking stupid. When confronted with an uncomfortable set of facts, the tendency is often to double down on their current position rather than publicly admit to being wrong.

Books resolve this tension. With a book, the conversation takes place inside someone’s head and without the risk of being judged by others. It’s easier to be open-minded when you aren’t feeling defensive.

Arguments are like a full frontal attack on a person’s identity. Reading a book is like slipping the seed of an idea into a person’s brain and letting it grow on their own terms. There’s enough wrestling going on in someone’s head when they are overcoming a pre-existing belief. They don’t need to wrestle with you too.

Why False Ideas Persist

There is another reason bad ideas continue to live on, which is that people continue to talk about them.

Silence is death for any idea. An idea that is never spoken or written down dies with the person who conceived it. Ideas can only be remembered when they are repeated. They can only be believed when they are repeated.

I have already pointed out that people repeat ideas to signal they are part of the same social group. But here’s a crucial point most people miss:

People also repeat bad ideas when they complain about them. Before you can criticize an idea, you have to reference that idea. You end up repeating the ideas you’re hoping people will forget—but, of course, people can’t forget them because you keep talking about them. The more you repeat a bad idea, the more likely people are to believe it.

Let’s call this phenomenon Clear’s Law of Recurrence: The number of people who believe an idea is directly proportional to the number of times it has been repeated during the last year—even if the idea is false.

Each time you attack a bad idea, you are feeding the very monster you are trying to destroy. As one Twitter employee wrote, “Every time you retweet or quote tweet someone you’re angry with, it helps them. It disseminates their BS. Hell for the ideas you deplore is silence. Have the discipline to give it to them.”

Your time is better spent championing good ideas than tearing down bad ones. Don’t waste time explaining why bad ideas are bad. You are simply fanning the flame of ignorance and stupidity.

The best thing that can happen to a bad idea is that it is forgotten. The best thing that can happen to a good idea is that it is shared. It makes me think of Tyler Cowen’s quote, “Spend as little time as possible talking about how other people are wrong.”

Feed the good ideas and let bad ideas die of starvation.

The Intellectual Soldier

I know what you might be thinking. “James, are you serious right now? I’m just supposed to let these idiots get away with this?”

Let me be clear. I’m not saying it’s never useful to point out an error or criticize a bad idea. But you have to ask yourself, “What is the goal?”

Why do you want to criticize bad ideas in the first place? Presumably, you want to criticize bad ideas because you think the world would be better off if fewer people believed them. In other words, you think the world would improve if people changed their minds on a few important topics.

If the goal is to actually change minds, then I don’t believe criticizing the other side is the best approach.

Most people argue to win, not to learn. As Julia Galef so aptly puts it: people often act like soldiers rather than scouts. Soldiers are on the intellectual attack, looking to defeat the people who differ from them. Victory is the operative emotion. Scouts, meanwhile, are like intellectual explorers, slowly trying to map the terrain with others. Curiosity is the driving force.

If you want people to adopt your beliefs, you need to act more like a scout and less like a soldier. At the centre of this approach is a question Tiago Forte poses beautifully, “Are you willing to not win in order to keep the conversation going?”

Be Kind First, Be Right Later

The brilliant Japanese writer Haruki Murakami once wrote, “Always remember that to argue, and win, is to break down the reality of the person you are arguing against. It is painful to lose your reality, so be kind, even if you are right.”

When we are in the moment, we can easily forget that the goal is to connect with the other side, collaborate with them, befriend them, and integrate them into our tribe. We are so caught up in winning that we forget about connecting. It’s easy to spend your energy labeling people rather than working with them.

The word “kind” originated from the word “kin.” When you are kind to someone, it means you are treating them like family. I think this is a good method for changing someone’s mind. Develop a friendship. Share a meal. Gift a book.

Be kind first, be right later.

Article:

Why do we have leap years? And how did they come about?

Leap years are years with 366 calendar days instead of the normal 365. They happen every fourth year in the Gregorian calendar — the calendar used by most of the world. The extra day, known as a leap day, is Feb. 29, which does not exist in non-leap years. Every year divisible by four, such as 2020and 2024, is a leap year except for some centenary years, or years that end in 00, such as 1900.

The name "leap" comes from the fact that from March onward, each date of a leap year moves forward by an extra day from the previous year. For example, March 1, 2023 was a Wednesday but in 2024, it will fallon a Friday. (Normally, the same date only moves forward by a single day between consecutive years.)

Other calendars, including the Hebrew calendar, Islamic calendar, Chinese calendar and Ethiopian calendar, also have versions of leap years, but these years don't all come every four years and often occur in different years than those in the Gregorian calendar. Some calendars also have multiple leap-days or even shortened leap months. In addition to leap years and leap days, the Gregorian calendar has a handful of leap seconds, which have sporadically been added to certain years — most recently in 2012, 2015 and 2016.

However, the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (IBWM), the organisation responsible for global timekeeping, will abolish leap seconds from 2035 onward.

Why do we need leap years?

On the face of it, all of this "leaping" may seem like a silly idea. But leap years are very important, and without them, our years would eventually look very different. Leap years exist because a single year in the Gregorian calendar is slightly shorter than a solar, ortropical, year — the amount of time it takes for Earth to orbit the sun once completely. A calendar year is exactly 365 days long, but a solar year is roughly 365.24 days long, or 365 days, 5 hours, 48 minutes and 56 seconds. If we did not account for this difference, then for each year that passes the gap between the start of acalendar year and a solar year would widen by 5 hours, 48 minutes and 56 seconds. Over time, this would shift the timing of the seasons. For example, if we stopped using leap years, then in around 700 years the Northern Hemisphere's summer would begin in December instead of June, according to the National Air and Space Museum.

Adding leap days every fourth year largely removes this problem because an extra day is around the same length as the difference accumulating during this time. However, the system is imperfect: We gain around 44 extra minutes every four years, or a day every129 years. To solve this problem, we skip the leap years every centenary year except for those that are divisible by 400, such as 1600 and 2000. But even then, there is still a tiny difference between calendaryears and solar years, which is why the IBWM have experimented with leap seconds.

But overall, leap years mean that the Gregorian calendar stays in sync with our journey around the sun.

The history of leap years

The idea of leap years dates back to 45 B.C. when the Ancient Roman emperor Julius Caesar institutedthe Julian calendar, which was made up of 365 days separated into the 12 months we still use in theGregorian calendar. (July and August were originally named Quintilis and Sextilis respectively but were later renamed after Julius Caesar and his successor Augustus.) The Julian calendar included leap years every four years without exception. It was synced up to Earth's seasons thanks to the "final year of confusion" in 46 B.C., which included 15 months totaling 445 days, according to the University of Houston.

For centuries, it appeared that the Julian calendar worked perfectly. But by the mid-16th century, astronomers noticed that the seasons were beginning around 10 days earlier than expected when important holidays, such as Easter, no longer matched up with specific events, such as the vernal, or spring, equinox. To remedy this, Pope Gregory XIII introduced the Gregorian calendar in 1582, which is the same as the Julian calendar but with the exclusion of leap years for most centenary years (as outlined above).

For centuries, the Gregorian calendar was only used by Catholic countries, such as Italy and Spain, but it was eventually adopted by Protestant countries, such as Great Britain in 1752, when their years began to greatly deviate from Catholic countries. Because of the discrepancy between calendars, countries that later switched to the Gregorian calendar had to skip days to sync up with the rest of the world. For example, when Britain swapped calendars in 1752, Sept. 2 was followed by Sept. 14, according to the Royal Museums Greenwich. At some point in the distant future, the Gregorian calendar may have to be re-evaluated as it slips out of sync with solar years. But it will take thousands of years for this to happen.

Why is Leap Day on Feb. 29?

In the eighth century B.C., the Roman calendar had just 10 months, beginning in March and ending in December. The cold winter season was ignored, with no months to signify it. But this calendar had only 304 days, so January and February were eventually added to the end of the religious year. As the last month, February had the fewest days. But Romans soon began associating these months with the start of the civil year, and by around 450 B.C., January was viewed as the first month of the new year. When Pope Gregory XIII added the leap day to the Gregorian calendar in 1582, he chose February because it was the shortest month, making it one day longer on leap years.

Sketchplanations

The Wheel of Death is a handy and simple tool to help prioritise issues and where to spend time fixing things.

I learned it from the domain of customer service. It's used something like this:

Keep track of customer issues that you encounter each week by tagging them. At the end of the week, tally up the responses and produce the Wheel of Death to see the highest volume of questions or issues taking up the team's time. Use the Wheel as part of a conversation about where the company should focus to improve the experience and save time for the team and customers.

The proportion of issues is only part of the story, and other factors like how critical the issue is, how much time it takes to resolve it, and how much work it is to make it go away will all be part of the decision.

I learned it from working with Mike Winfield, a talented head of customer experience, as we worked on fixing support issues, though don't confine its use to that. I find "the Wheel of Death" a name that sticks with me, but it could also be called the Wheel of Fortune. If you focus on the Wheel for a spell, it's hard for things not to improve.

Remember that you'll need to combine it with volume or time metrics in its form as a pie chart, or it can look like you're not making progress.