Editorial

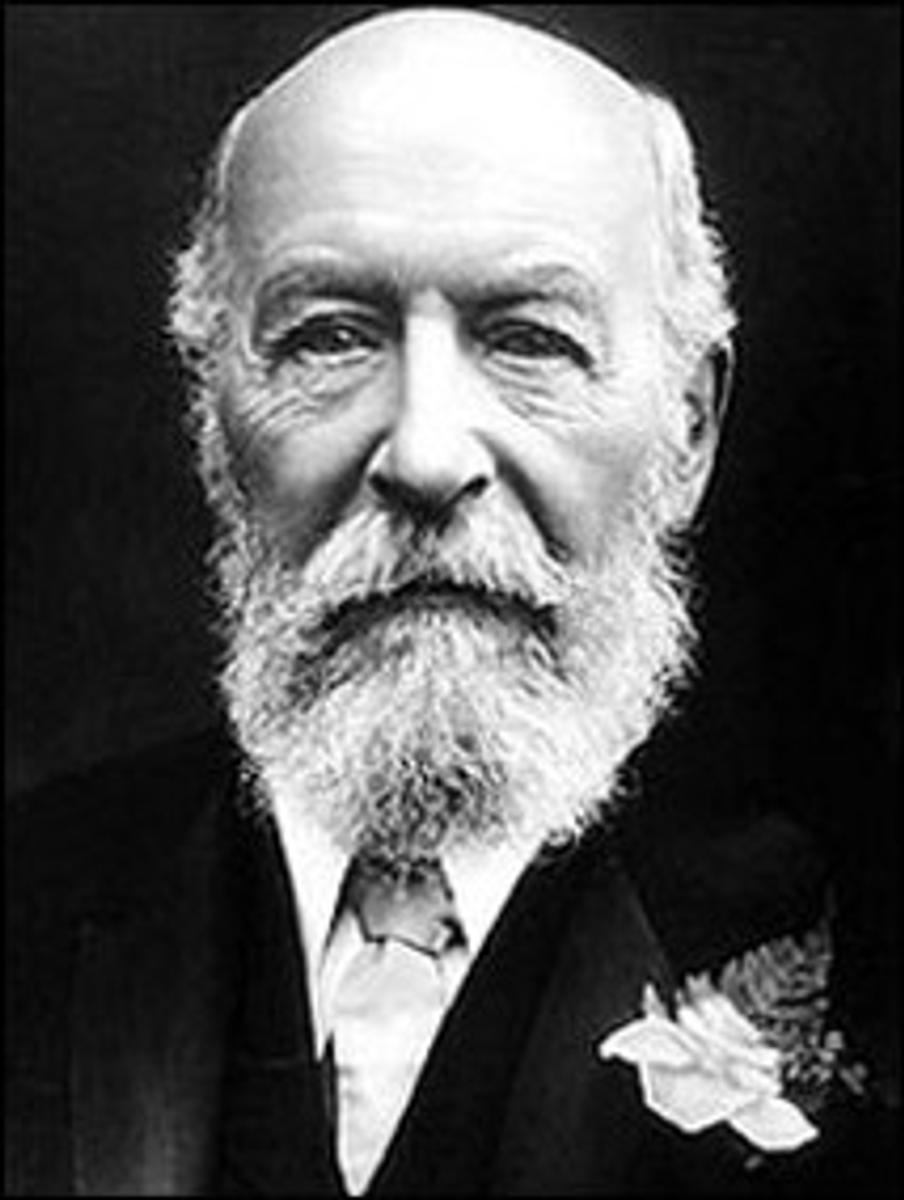

Gliding through the supermarket (no wonky wheels for me!) at this time of year, I see things in my trolley I don’t normally see. This week my eye was drawn to Cadbury ‘Bournville' baking cocoa. This is not because I was thinking of yummy chocolate cake (although I am now), but because of the origin of that name. Bournville in Birmingham UK, was the name of the town that George Cadbury, of the chocolate company fame, built for his workers near his factory.

It became known as the “factory in the garden”. Such was his care for his employees that even to this day it is regarded as "one of the nicest places to live in Britain". He also gave his retired employees a pension, unheard of at the time. Furthermore, he built a hospital, schools, a park for the people of Birmingham and a house in the countryside for kids in the city slums to have a holiday. This is even more remarkable as this occurred during the Industrial Revolution; a time when it became normalised for bosses to send children as young as five down mine shafts and into factories. People had become merely ‘factors of production’ in the worship of an alternative ‘gospel’ of wealth.

Why would Cadbury do this? How could he be so radical? He was clearly following the contours of a very different gospel. He understood Lordship and the ‘good life’ in a way most others didn’t.

Let’s go back to a time when another secular ’gospel’ was proclaimed. This term was applied specifically to the ruler of Rome: Caesar. He was presented as the means to the ‘good life’, the bringer of salvation, indeed God appearing as a person. “Caesar is Lord” was not just a declaration of pragmatic political allegiance, but an act of worship.

Into this world of Roman occupation of the Promised Land, Jesus was presented an impossible question: are we to pay tax to Caesar? (Matthew 22:15-22) Does he legitimise Jewish sovereignty and deny the lordship of Caesar? Does he legitimise Roman sovereignty and deny the Lordship of God?

It seems like Jesus is trying to have a bit each way, and in doing so divide the spiritual and the secular: “Give back to Caesar what is Caesar’s and to God what is God’s.” (v. 21) However, let’s go back a bit – in response to this question he asks for a coin used to pay the Imperial tax: “Whose image is this?” His audience knows this term well – the Scriptures open with all humans being made in God’s image. This person whose image is on the coin only derives his ultimate authority in the bearing of God’s image. Jesus is putting the idolatrous claim of Caesar being divine in its proper perspective. We may be obliged, as a recognition of the authority bestowed by God in human government, to give a coin in tax, but if we give that which bears God’s image, we give everything. It is a declaration that Jesus is Lord.

George Cadbury understood this lordship. The gospel of Jesus, in which Cadbury revelled despite his culture seeking alternative gospels, meant he truly understood the good life and the task given him as a representative of God. As an act of worship, he pursued these for those who bore his Lord’s image.

This Christmas there are many gospels of the good life – holidays, big lunches, family, chocolate cake (are you still thinking about this?). How do we understand these in a proper perspective? How do we understand the well-worn phrase, ‘Jesus is Lord’? Let’s talk with our kids about what it is to seek the good life for those who bear God’s image.

Doug Allison

Secondary Teacher & Humanities Faculty Leader