The Green Page:

Corals Send an Ultimate SOS Before Turning into a Massive Graveyard

The widest-ever coral bleaching is underway, and there is only one way to save them.

Contrary to popular belief, coral isn’t a plant, and it isn’t white. Those are two misconceptions that need to be cleared up. Coral is actually a marine invertebrate that forms colonies of polyps, creating a symbiotic relationship with zooxanthellae algae: the algae provides energy through photosynthesis and colourful pigments, while the coral offers shelter and nutrients.

Together, these creatures are the architects of the sea, fostering a quarter of all marine species while covering less than 1% of the ocean area.

But these relationships are fragile. When corals are stressed for long periods, they expel algae from their tissues, losing their main source of energy and nutrition, their vibrant colours, and their susceptibility to death.

You’ve probably seen images of bleached coral. They look beautiful, their bone-white skeleton seen through their translucent flesh. But when you zoom in, it’s clear that they’re ill, fleshless, and dying. Corals are extremely vulnerable to global warming. They can survive bleaching if temperatures aren’t too high or too long. On the contrary, extreme marine heatwaves can kill them outright.

And every day, for more than a year now, the global average sea-surface temperature has been at a record seasonal high in data that goes back to 1979. And those historical records haven’t just been narrowly surpassed; they’ve been obliterated.

This has pushed coral reefs towards the 4th and worst worldwide mass bleaching event on record.

A Deafening SOS

“From February 2023 to April 2024, significant coral bleaching has been documented in both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres of each major ocean basin,”said Derek Manzello, Ph.D., NOAA Coral Reef Watch coordinator.

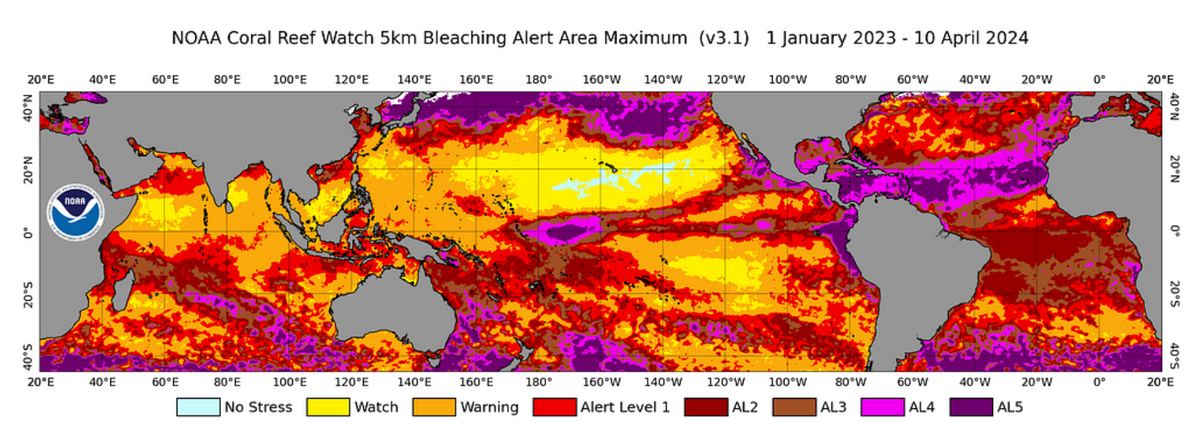

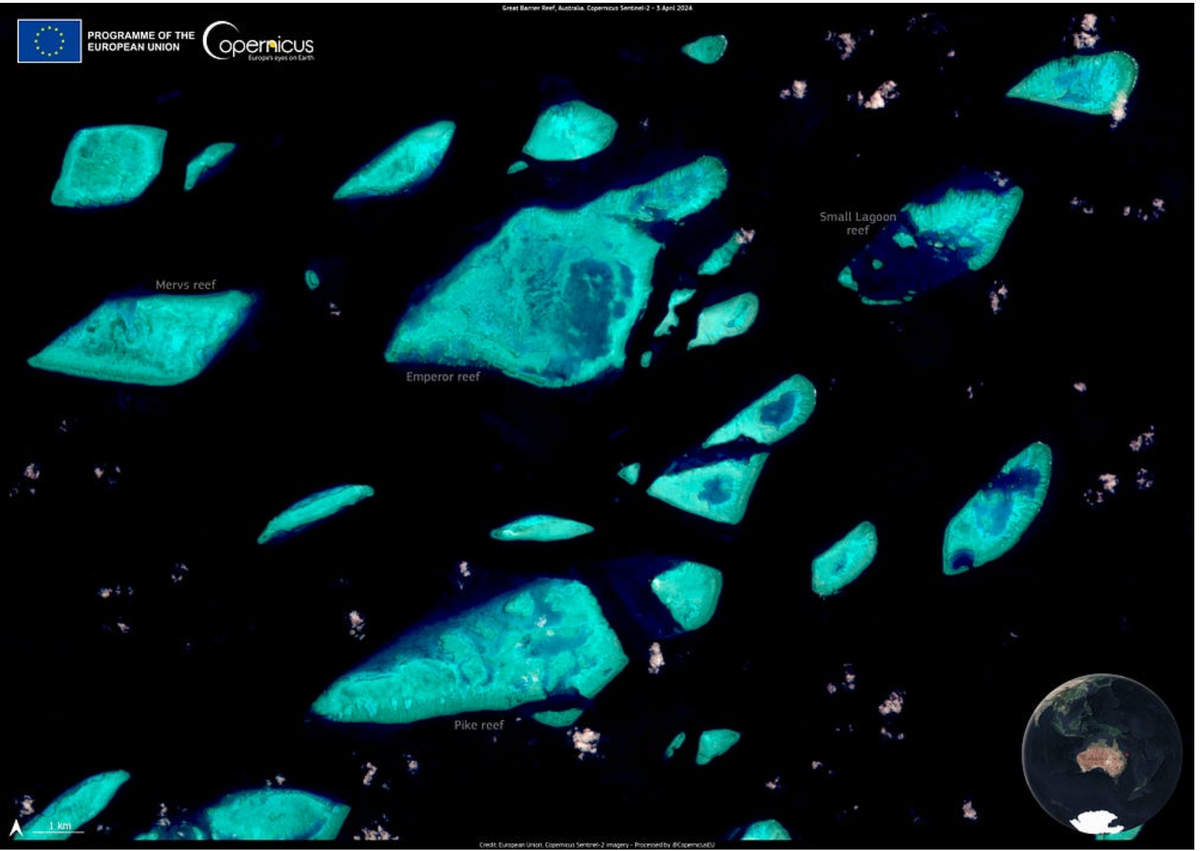

A global bleaching event is declared when at least 12% of corals in each main ocean basin experience extreme heat stress within a year. Today, an alarming 54% of ocean waters housing coral reefs are rampant with mass bleaching in the tropics, the Caribbean, Brazil, the eastern Tropical Pacific, large areas of the South Pacific, the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf, and the Gulf of Aden. Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, a global icon, is having its worst mass bleaching event in eight years, with 80% of the reef affected, far exceeding the previous high of 60% in 2017.

NOAA Coral Reef Watch’s global 5km-resolution satellite Coral Bleaching Alert Area Maximum map, for January 1, 2023 to April 10, 2024. This figure shows the regions around the globe that experienced high levels of marine heat stress (Bleaching Alert Levels 2–5) that can cause reef-wide coral bleaching and mortality.

The first global bleaching event in 1998 saw 20% of the ocean’s reef corals exposed to heat stress high enough to cause bleaching. The figures rose to 35% in 2010 and an unsettling 56% from 2014 to 2017.

Manzello warns that the present bleaching event is on track to exceed the disastrous 2014–2017 global bleaching record. Why?“Because the percentage of reef areas experiencing bleaching-level heat stress has been increasing by roughly 1% per week”.

Bleaching Roots

Over 90% of the excess heat generated by human-induced global warming is absorbed by our oceans. This absorption creates the illusion that climate change is a slow, manageable process. It’s not. Our oceans are now battlegrounds for extreme temperatures, shattering records day after day. And they’re not just warming up; they’re also acidifying and losing oxygen, wreaking havoc on marine ecosystems. From 1971 to 2018, the ocean has absorbed a staggering 396 zettajoules of heat — over 25 billion Hiroshima atomic bombs. And this rate of heat gain is accelerating.

The global average sea-surface temperature usually peaks in March — the Southern Hemisphere’s summer end. However, last year, temperatures hit an all-time high in August and broke the record again this year. Scientists have theories but no certainties about what’s happening.

One likely culprit is El Niño, a natural climate pattern originating in the Pacific Ocean along the equator that tends to increase global temperatures and has been a significant factor in the record-breaking ocean heat.

The current global event began last summer in the northern hemisphere. The alarm bells first rang from Florida’s southern tip when an extraordinarily severe and long-lasting heatwave led to hot tub-like sea temperatures. This rapid heat increase led to an acute heat shock response in soft corals, essentially disintegrating them and turning entire colonies into graveyards.

This deadly combination then moved into the southern hemisphere, leading to 98.5% of Atlantic reef areas experiencing bleaching-level heat stress.

And then it expanded worldwide.

Extreme bleaching event in the Great Barrier Reef (Source: Copernicus)

The Future: La Niña and Coral Resilience

NOAA is forecasting the arrival of La Niña, the cooler flip side of El Niño, between June and August this year, which provides “a nugget of hope.”

But bleaching events have still happened during La Niña years.

“I am becoming increasingly concerned about the 2024 summer for the wider Caribbean and Florida.When we roll into summer and the bleaching season for Florida and the Caribbean, it won’t take much additional seasonal warming to push temperatures past the bleaching threshold.The bottom line is that as coral reefs experience more frequent and severe bleaching events, the time they have to recover is becoming shorter and shorter.Current climate models suggest that every reef on planet Earth will experience severe, annual bleaching sometime between 2040 and 2050,”Manzello said.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change projects that if global warming exceeds the 1.5°C limit set by the Paris climate agreement, 70–90% of existing reefs will be severely diminished or dead. If the world hits a warming of 2°C, which is expected at current rates by 2050, nearly 99% of Earth’s corals will die. Over the past year, global temperatures have been the highest ever recorded, 1.58°C above the pre-industrial landmark (though it won’t be considered breached until this trend persists for a decade).

Coral can bounce back from heat stress, but it requires time — several years, ideally. However, weakened coral is disease-prone and can die easily. Recent research led by Jennifer McWhorter from NOAA offers a ray of hope. It shows that corals living in cooler, deeper waters (30–50m depth) in the Great Barrier Reef could survive global warming of up to 3°C compared to shallow corals as the planet heats up.

The harsh reality is we must accept that reefs as we know them will change forever. Small-scale restoration cannot save coral globally. Corals are transitioning from being homes and buildings for marine life to mere scaffolding.

But who wants to live in scaffolding?

The Only Way to Save Coral Reefs

The economic value of the world’s healthy coral reefs has been estimated at $11 trillion annually.

They not only provide thriving ecosystems for scuba divers and form the backbone of coastal fisheries but also protect the shorelines from some of the worst impacts of tropical storms and hurricanes.

“During big storms, the waves are 10 meters outside the reef, but the corals break the waves and they’re only 3 meters when they reach the shore. But that barrier doesn’t exist anymore,” said Brigitta van Tussenbroek, who studies coastal ecology in Puerto Morelos, Mexico.

Diseases, polluted runoff, and sargassum seaweed are just a few other threats they face, in addition to the increased warming of waters. And yet, despite all this, we continue to burn more fossil fuels and increase greenhouse gas emissions.

In 2020, fossil fuels received a subsidy of $5.9 trillion, or 6.8% of GDP, with an expected increase to 7.4% of GDP in 2025. That’s $11 million a minute. For every dollar invested in combating climate change, at least five times that amount is spent subsidizing the very thing that’s killing us.

While mainstream messaging focuses on potential solutions like “super corals” or “cryogenically frozen reefs” that can better withstand the increasing heat of the ocean, these are merely stopgaps. They are important, yes, but that’s only because they can buy some necessary time for corals. The best way to save the reefs probably isn’t in a lab.

Julia Baum, a marine ecologist and conservation biologist at the University of Victoria, put it bluntly: “The only real solution for coral reefs now is a rapid phase-out of fossil fuels.”

The energy transition is our best chance of saving coral reefs. As earthlings, messengers, and part of the collective efforts for a better, sustainable future, we need to start being honest brokers about this fact. Because this is not just about the corals. It’s about us, our future, and the future of our planet. Let’s be clear and assertive about this.

Once coral has died, marine creatures that navigate using coral noise can struggle to find their way home. Will we heed the SOS call corals are sending worldwide and find a sustainable path forward?

Be loud.