Teaching & Learning Page:

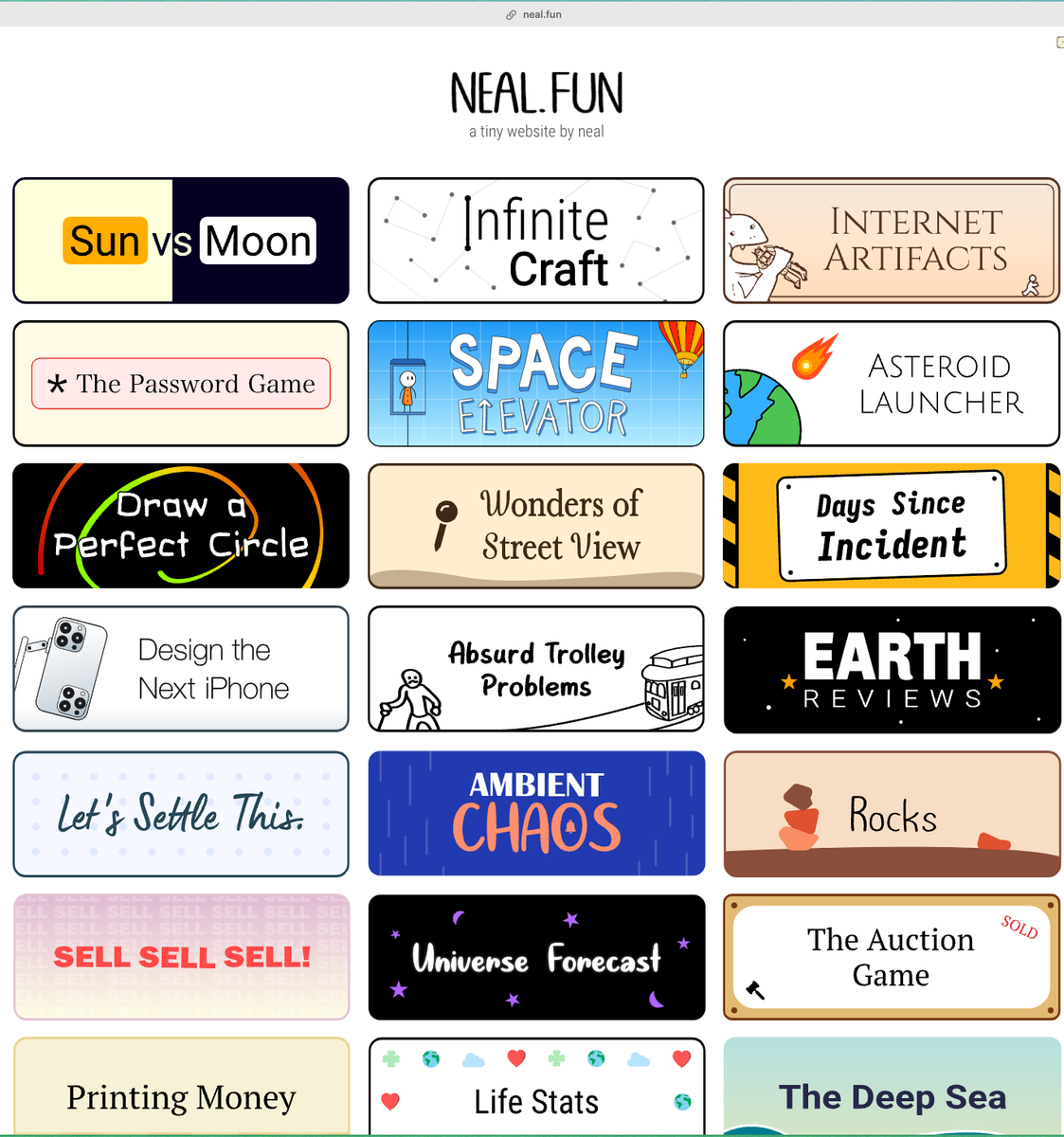

Web Pages:

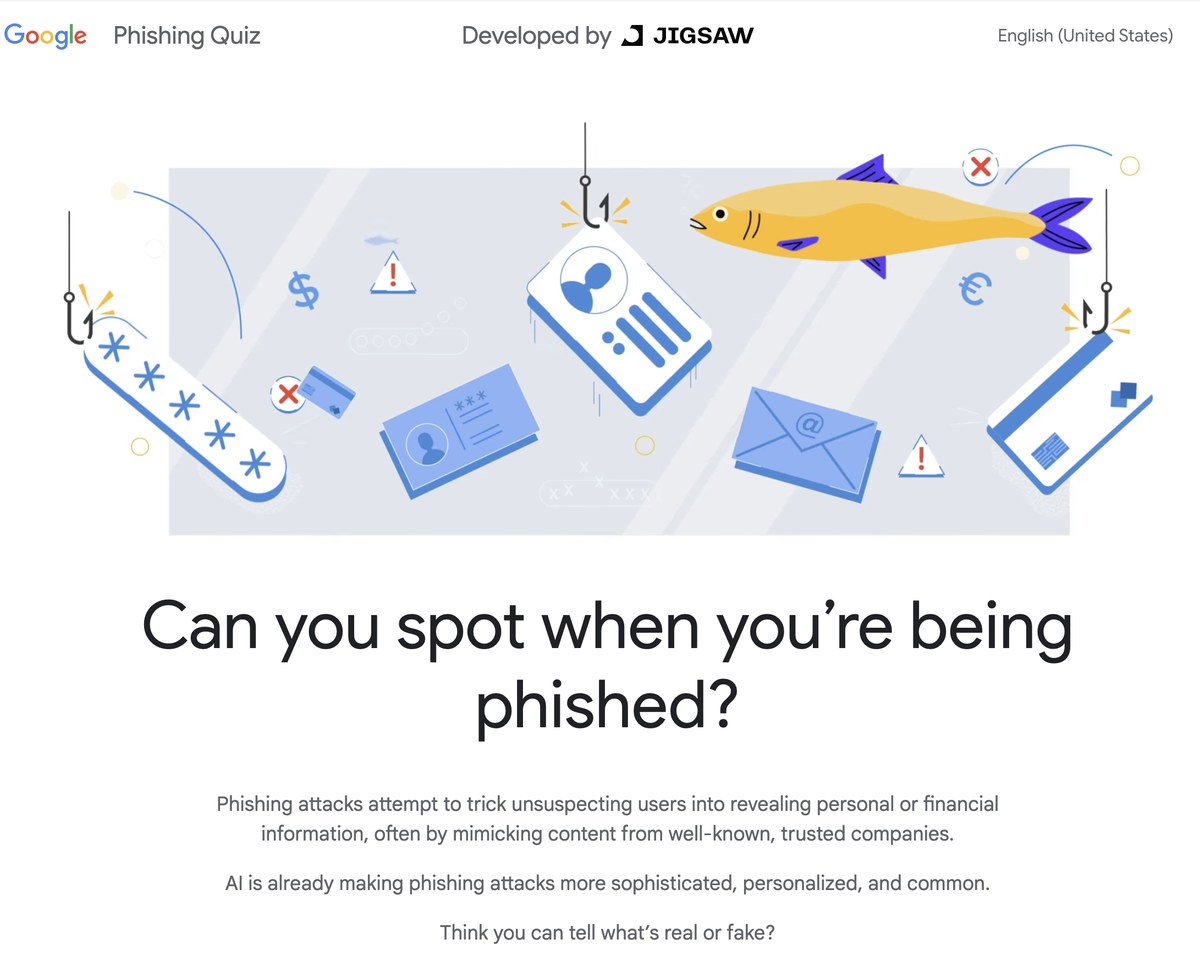

https://phishingquiz.withgoogle.com/?ck_subscriber_id=32120958

Ways to Teach Gratitude in Your Classroom

There are many reasons that students may struggle with gratitude.

I like this definition of gratitude and its benefits from Psychology Today:

“Gratitude is an emotion expressing appreciation for what one has—as opposed to what one wants or needs. Gratitude is what gets poured into the glass to make it half full.

Studies show that gratitude can be deliberately cultivated and can increase levels of well-being and happiness among those who do cultivate it. In addition, grateful thinking—and especially expression of it to others—is associated with increased levels of energy, optimism, and empathy.”

Being grateful has real, tangible benefits. Gratitude is worth cultivating and does much to improve our mental and physical well-being.

1. Keep a Joy Journal.

Research studies have shown that keeping a 5-minute daily gratitude journal will increase long-term well-being.

Talk about this with students, set a timer, and keep a joy journal every day for the next two weeks. Ask older students to plot their moods to see if they notice any change in their outlook on life. When it is time to create gratitude artwork, review your journal for patterns of things that bring you joy. Successful classrooms show gratitude, and gratitude shouldn’t be a secret. Help children share a word of thank you with each other and with those who care for and help them every day.

Benefits: This activity can have students writing, journaling, and improving their mood at the same time. You can also encourage parents to join in this activity and educate them on this.

2. Show gratitude to each other

It takes as many as ten compliments to counterbalance one criticism. Research shows that the highest-performing teams have a ratio of almost six compliments for every negative one. (The lowest have almost three negative comments for every positive one.)

Encourage children at regular intervals to give one genuine compliment to every other student. Typed them up and put a picture of each student in front (with classmates behind) with a title like “why we’re thankful for ___ (Suzie or Johnny or insert name there.) The teacher should add one there as well.

Benefits: This activity helps students show gratitude towards each other and to intentionally say thank you and can have an impact on the whole class, particularly in helping them appreciate the strengths of each child.

3. Show gratitude to others who serve

There are so many people who do so much for our children at school. Showing gratitude to each person on staff in meaningful ways can make a huge difference. You can start by asking students to give a genuine verbal compliment and discuss the response they receive.

Then, you can level up and have students write thank you notes or cards or use their art as a form of recognition and thank you to those who encourage and care for them.

Benefits: The entire school begins to be reminded to be grateful for one another.

4. Show gratitude to parents and family

Students often take their caregivers for granted. Encourage students to take time to write parents a note or to list all of the things they are grateful for from their parents. Use these thoughts to inspire artwork.

Benefits: strengthen the home/school connection and encourage parents to show gratitude to their children as well.

Password Activity for children - useful for adults too.

Techie Tips:

Mac OS General Shortcuts I Cannot Live Without:

Command + Space / Command + Return — Activating Spotlight / Alfred.

Command + Q — Quit an application.

Command + Tab — Switch between the last application.

Command (Hold) + Tab, then Tab Tab Tab Tab — Switch between any opened applications.

Command + H — Hide the current application.

Command + Option + Q — Force quit an app (when something is lagging).

Command + , (comma) — Open settings in most apps.

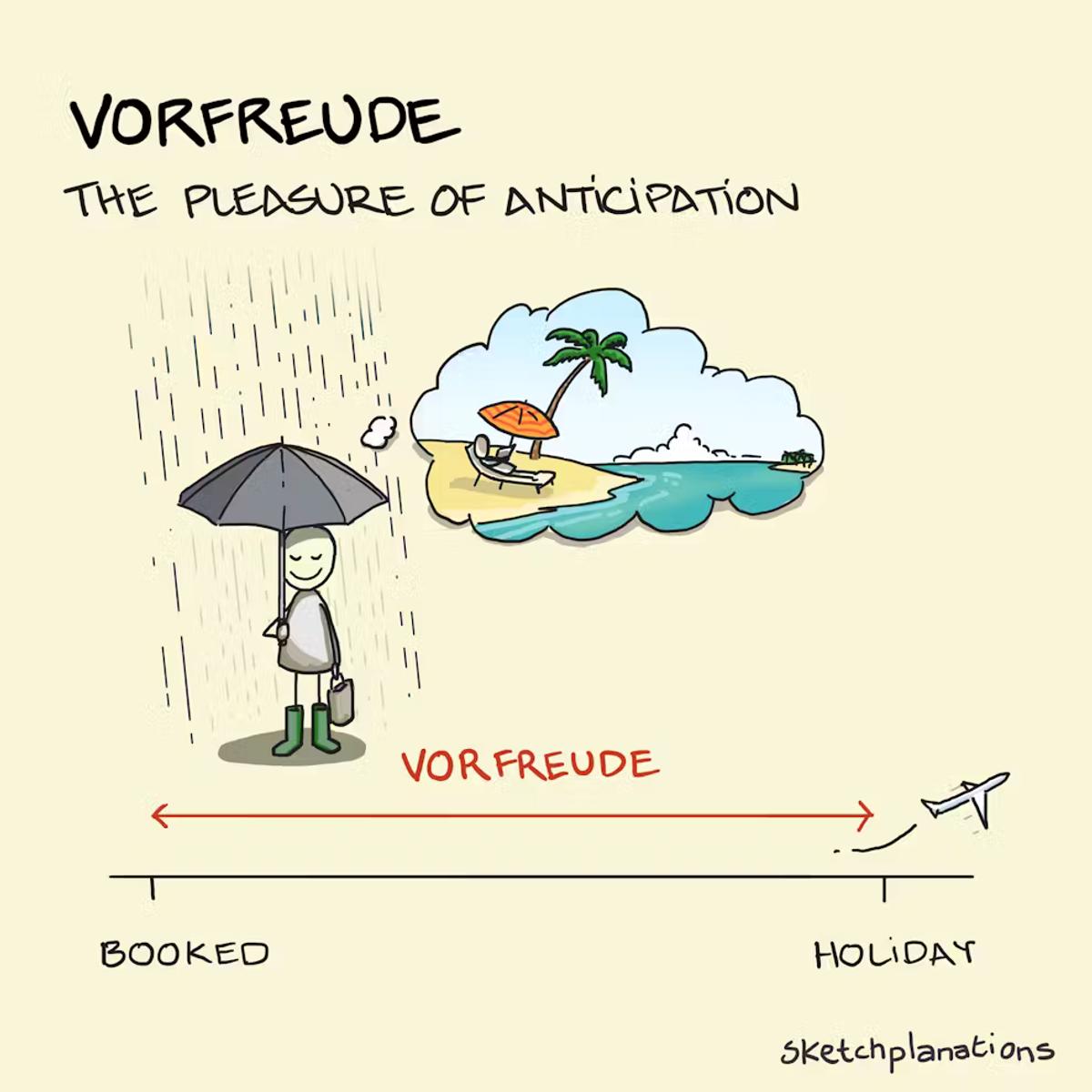

Sketchplanations:

Vorfreude is a delightful German word for the pleasure of anticipation. It combines vor, meaning "before" or "in advance", and freude, meaning "happiness". It's the joy from the anticipation of joy.

For me, the magic of vorfreude lies in how it stretches out the pleasure of any upcoming event or experience. Once I hit 'Confirm' to book a trip, it kicks off joy for months whenever I think about the trip. And the great part about it, if we're organised, is that a trip in December can bring 'anticipatory joy' from when we book it in January. I need only reflect on my positive feelings about the trip, and life seems better.

I've often found that the vorfreude may surpass the joy of the actual trip. With my vorfreude glasses on, I never worry about the mosquitoes, the heat, or the inevitable waiting on the journey.

Thanks to something called fading affect bias, the emotional weight of negative memories tends to fade faster than positive ones. This leaves us with a rose-tinted view of past trips and may conveniently erase the niggly parts we didn't enjoy, allowing us to focus on just the good parts of a trip coming up. Or perhaps it's our optimism bias (we had a fun podcast on that).

Vorfreude doesn't only apply to big events like a holiday or wedding. I find anticipatory joy in small things, too. I look forward to the first coffee in the morning every day. Sometimes, the coffee won't live up to what I'd hoped for, but I'd already been enjoying the idea since I finished my last coffee the day before.

I look forward to meeting friends and loved ones. I look forward to a dinner out. I look forward to weekends. I look forward to the next football match. I look forward to a cake coming out of the oven. Many people look forward to 5 o'clock day. By simply reflecting on these moments of future joy, we can experience happiness right now, no matter where we are.

We can even work to cultivate and enhance our vorfreude. As a child, nothing built anticipation like an advent calendar, ramping up excitement for Christmas day as I opened each new window. Sharing photos of your holiday destination with friends and family before you go and planning activities increases vorfreude. Getting good things in the diary can kick us out of languishing.

In some ways, vorfreude mirrors the benefits I get from fear-based training plans or the forcing function of signing up for endurance events later in the year—having signed up for the event, I start to benefit from it as soon as I get out training with friends.

But don't forget to enjoy the moment. I'm sometimes reminded of Calvin talking with Hobbes about the enjoyment of his favourite breakfast cereal, Chocolate Frosted Sugar Bombs:

"Ahhh, another bowl of chocolate frosted sugar bombs! The second bowl is always the best! The pleasure of my first bowl is diminished by the anticipation of future bowls, and by the end of my third bowl, I usually feel sick."

While it’s great to savour the anticipation, remember to enjoy the moment when it arrives.

More tips for vorfreude in this excellent article by Rachel Dixon: The vorfreude secret: 30 zero-effort ways to fill your life with joy

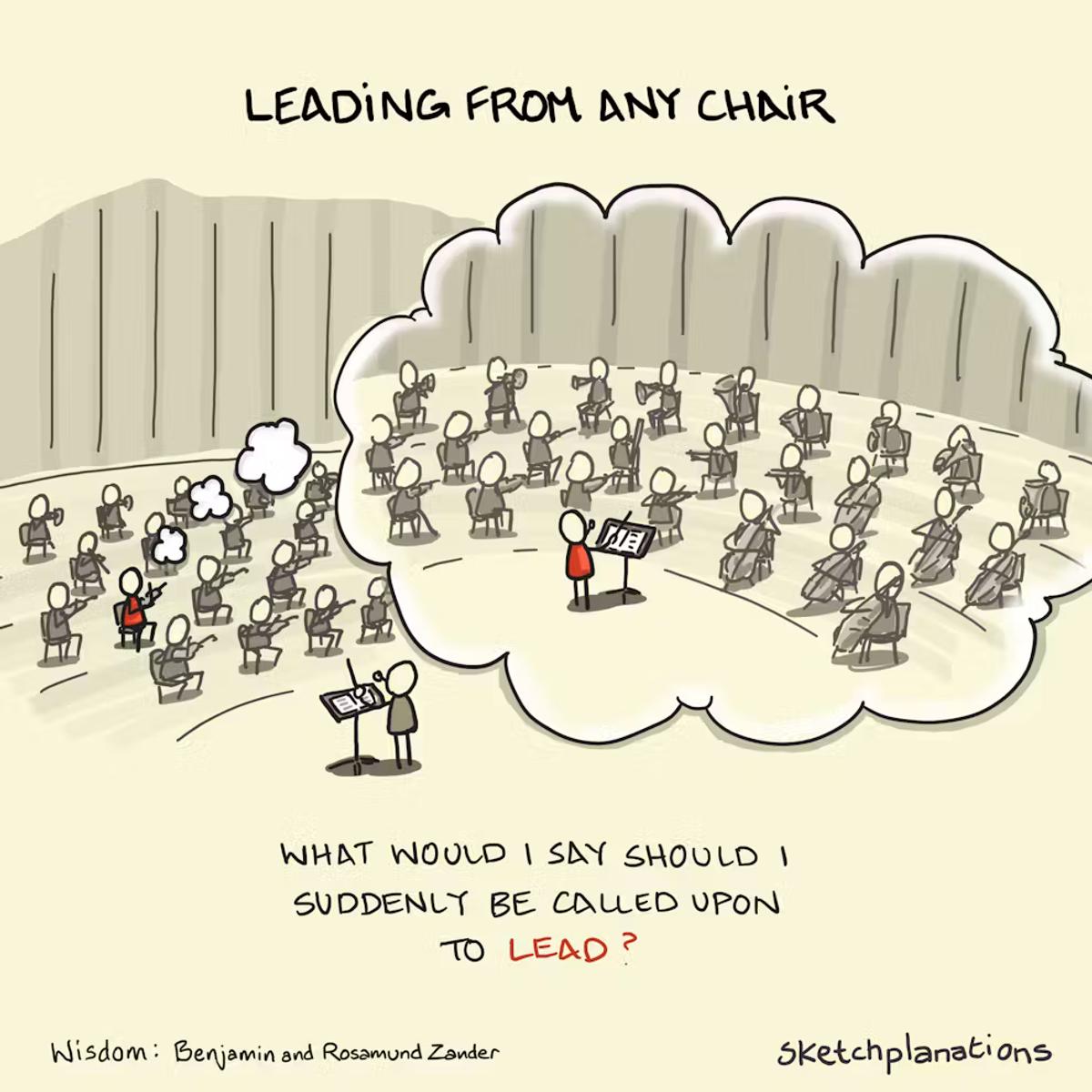

Leading from Any Chair is the idea that we all have the opportunity to influence the action even when we're not standing at the front. It's a principle for effective leadership and teaching yourself and others to lead.

A story

In their inspiring book, The Art of Possibility, Benjamin and Rosamund Zander relate a story from renowned violist Eugene Lehner, who played in the Kolish Quartet and Boston Symphony Orchestra. One day, in an interpretation class led by Zander with Lehner as a guest coach, Ben Zander asked him, "How can you bear to play day after day in an orchestra led by conductors, many of whom must know so much less than you?"

Lehner said he was playing in a rehearsal in his first year in the orchestra when the conductor, Koussevitsky, struggled to lead the orchestra as he wanted through a tricky Bach piece. A friend of Koussevitsky and fellow conductor, Nadia Boulanger, was sitting in on the session. Koussevitsky stopped and asked if Nadia would conduct the passage so he could hear what it sounded like from the back of the hall. Nadia conducted the passage without a hitch, and the rehearsal continued. But the episode left Lehner ever wondering and waiting for the moment when a conductor might say to him, "Lehner, you come up here and conduct. I want to go to the back of the hall and hear how it sounds."

"It's now 43 years since that happened," said Lehner, "and it is less and less likely that I will be asked. However, in the meantime, I haven't had a single dull moment in a rehearsal as I sit wondering, 'What would I say to the orchestra, should I suddenly be called upon to lead?'"

Stepping up to lead

There are many occasions when I have personally grappled with whether now is the moment to step up and lead. Sometimes, I have taken them. Other times, I feel ashamed that I sat back and let events unfold without contributing.

It's the easy path to defer to whoever's leading and consider that there may be better times to influence or say what you think needs to be said. Or you can take the view that we're all responsible in some way for what we're experiencing, and we all have the opportunity to influence for the better.

You don't have to be the captain on the field to influence your fellow players.

A typical example I've experienced is seeing a presenter struggle in a meeting, perhaps with technical difficulties or audience confusion. It may take only a little to try and help with the tech or to ask the presenter to explain a point that you see needs to be clarified for people. Or, as an audience member, you can sit back and consider it not your problem.

Once, in the middle of a performance at a wedding, the music suddenly clicked off for the performer. Immediately picking up on the problem, the wedding photographer started singing the melody, picking up where the music left off. Getting the idea, all the guests joined in, continuing the music to the end. This quick intervention undoubtedly led to a better show for everyone, including the performer.

Learning to lead

When you choose to step up, it's an opportunity to learn to lead. You may discover that there's more to leading than it seems and gain empathy for the leaders around you.

By constantly asking myself, "What would I say should I suddenly be called upon to lead?" I am mentally rehearsing for when I am needed, for when I am in the position of a leader. It speeds up my learning and keeps me always ready for action.

It's one reason why always thinking of questions at a talk or conference is valuable. It forces you to engage with the material, and when the opportunity arises, you're ready to step up and ask about what matters to you or what everyone is thinking.

Identifying passion and the leaders in front of you

As a leader, if you believe you are superior, for example, as the conductor who doesn't consider the orchestra members to have anything to contribute to the interpretation of the music, then you are likely to suppress the voices of the very people you need to deliver.

People want to contribute—that's why they attended the class, joined the company, or trained in their discipline. Rosamund Zander advises that, as a leader, we can train ourselves to spot the passion of the people in our teams. We can actively look for occasions to allow team members to lead. And if we don't see the passion, we can ask ourselves the beautiful and challenging question:

"Who am I being that they are not shining?"

Leading from Any Chair

We can learn to lead at any time. So the next time you're just one in a crowd, consider that you can lead from any chair. Ask yourself, "What would I say if I were suddenly called upon to lead?"

--

In case it wasn't clear, I highly recommend The Art of Possibility, which I listened to as an audiobook read by Benjamin and Rosamund. And I always recommend finding 20 mins to watch Benjamin Zander's classic TED talk, The Transformative Power of Classical Music. Left-buttock playing is a sketch I've been planning for a long time.

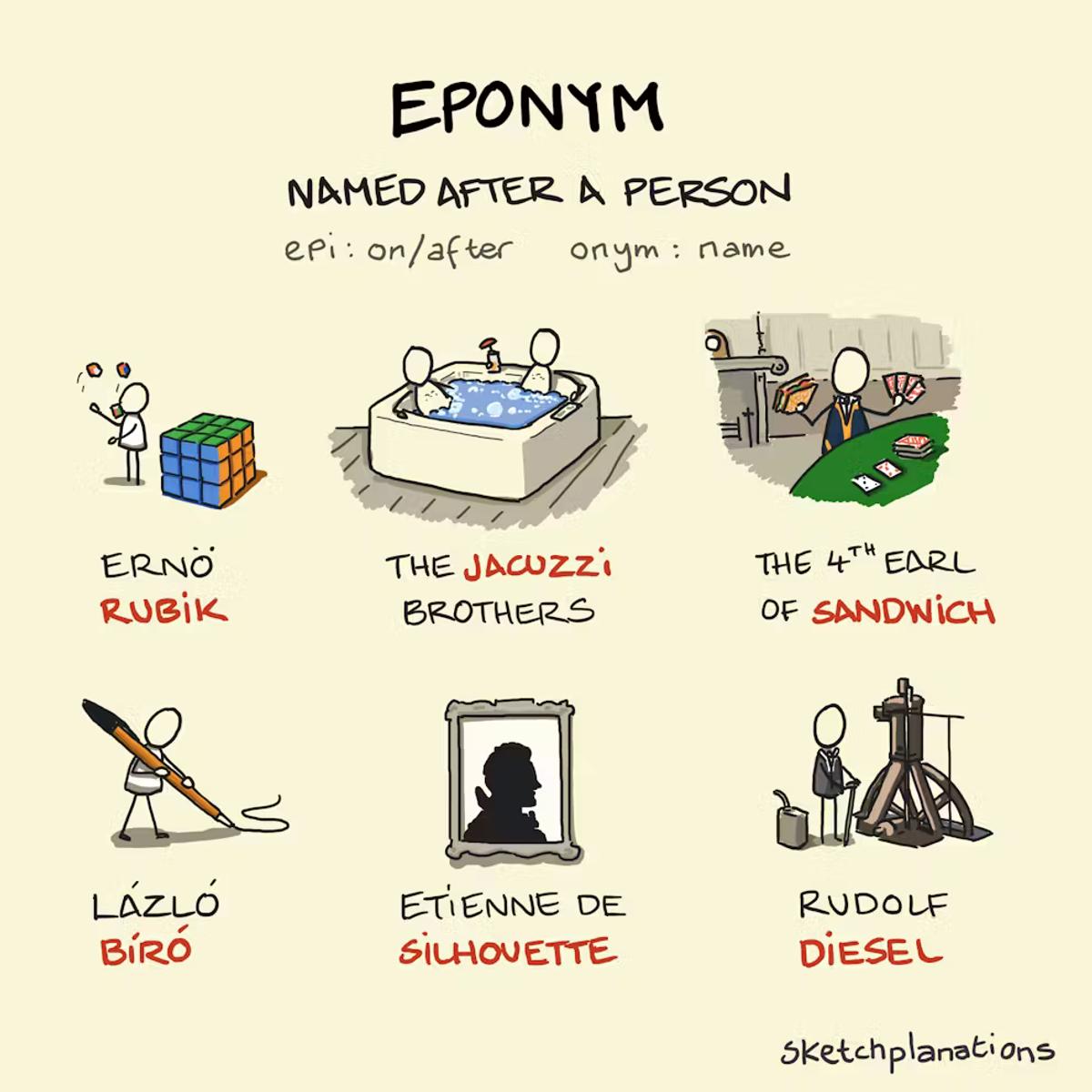

An eponym is a word named after somebody or someplace.

An eponym, almost by definition, comes with a story, making them some of the most intriguing words. Knowing what an eponym is also allows you to use the word eponymous, which is always a good way to sound smart.

Some of my favourite eponyms are now commonplace products that took the inventor's name. Some examples:

The Rubik's Cube

The Rubik's cube is an invention by Hungarian architecture professor Ernő Rubik. It is fascinating because it is both a solid and fluid object.

This year (2024), the Rubik's Cube turned 50, celebrating around half a billion cube sales, scores of speed-cubing championships, and documentaries. When Rubik first invented the cube, he wasn't sure it was solvable and only managed it for the first time several months after creating it.

In 2020, Rubik told the story of the cube in his book, Cubed: The Puzzle of Us All.

The Jacuzzi

The fabulously named jacuzzi, or more generally the hot tub, is named after the Italian Jacuzzi family. The seven brothers of the family—there were also six daughters—trained to become engineers, making plane propellers, irrigation systems and pumps before one of the brothers created a homemade bath to help his two-year-old son who was suffering from rheumatoid arthritis. The rest, as they say, is history.

Saskia Solomon tells some of the brothers' story, which includes the court case Jacuzzi vs Jacuzzi, and the invention of the jacuzzi in the 2023 New York Times article, The Frothy Saga of the Jacuzzi Family.

The Sandwich

After so long as what seems the most basic of foods, it was remarkable for me to learn that the humble sandwich was named after a person: John Montague, the 4th Earl of Sandwich. Though he probably spent most of his time in London, the title itself is associated with the small town of Sandwich in Kent, in Southeast England.

The story goes that the Earl liked playing cards and wanted food he could eat without having to leave his game and that wouldn't give him sticky fingers that would damage the cards. Incarnations of open sandwiches appeared much earlier elsewhere. For example, the trencher—something I had to look up when reading Game of Thrones—involved serving food on top of old bread as a sort of plate. But it took the Earl's dedication to card playing, or at least desk work, to take the next step many years later.

The Biro and BiC ballpoint pens

László Bíró was a Hungarian-Argentine inventor who created the first truly successful ballpoint pen. In the US, the BiC is more common, an eponym this time from Marcel Bich.

It's said that Lázló experienced his fountain pen leaking from heat—fountain pens being very common before the ballpoint—and was inspired by a printing press that used a cylinder to spread the ink. All it needed was to go in all directions. Enter the ballpoint.

While the invention seems obvious in hindsight, perfecting it for robust, commercial use was challenging. For example, finding suitable ink for the tiny ball bearing to spread, which doesn't leak or clog and isn't overly affected by heat. Lázló teamed up with an aviation company—who use a lot of ball bearings—which also provided a great use case of finding a pen that wouldn't leak from the air pressure changes in planes. Later, BiC licenced the technology from Biro. A Bic Cristal® Ballpoint pen is part of the collection at the MoMA.

Silhouette

I only learned that silhouette was an eponym while preparing this sketch, but it's perhaps the best of all. Étienne de Silhouette, a French government finance official tasked with curbing a French deficit in the 1700s, unwittingly gave his name to the classic black-on-white simple outline image of a person. His severe frugal policies of taxes, curbing royal spending and even melting down gold and silverware earned him the reputation of doing things cheaply. Hence, a cheap method of creating a portrait, cutting out black paper and laying it on a white background, became known as a silhouette.

Diesel

Nearly everyone will recognise the fuel that Rudolf Diesel gave his name to and his diesel engine. Diesel created a breakthrough engine that was more efficient than typical steam engines while being smaller and weighing less.

Curiously, I learned that Diesel died in mysterious circumstances, disappearing on a journey across the English Channel in 1913.

--

An excellent episode of the 99% Invisible podcast featuring Helen Zaltzmann of the Allusionist raised several interesting questions about eponyms I hadn't considered. Here are a few to think about:

Eponyms are common in medicine, for example, when we name a disease or condition after those playing a part in the discovery. However, the name, for example, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, tells a medical practitioner very little about the disease compared to a name that relates to the symptoms of the sufferer or the cause. Should examples like these be replaced with more practical names?

Eponyms almost always have a way of oversimplifying a story, often wrapping up complex histories with the names of white males. For example, rarely are products invented or diseases identified solely through the actions of one person. Yet an eponym chooses one, or some people, at the expense of others.

Eponyms may be the name of someone later discredited or who develops a tarnished reputation from other actions in their lives. Should someone who did evil deeds be remembered in an eponym or should it be changed?

Who knew eponyms could be so interesting?

Eponyms are distinct from the fun concept of Nominative determinism—an aptronym—where someone's name seemingly influenced their future actions or career choices (for example, Les McBurney — Volunteer firefighter).

Article - From

The Why of Halloween

Halloween’s origin story begins with the Celtic celebration of Samhain (translation: “summer’s end”). Samhain was an agricultural festival that started at sundown on October 31 and ended at sunrise the next day. It marked the transition from harvest season to the “dark half” of the year, which was traditionally associated with death (today, we call it “winter”).

The Celts believed that on this liminal night, the veil between worlds was at its thinnest — a moment “when the normal order of the universe is suspended,” according to historian Nicholas Rogers. What actually unfolded during Samhain is up for debate because much of ancient Celtic history was “recorded by medieval Christians. That means it’s very difficult to tell how many of the ideas associated with Samhain are authentically pre-Christian, and how many arose after Christianization.”

There’s no denying Halloween’s ties to Christianity: The Pope established it to accompany All Saints’ Day, a holiday honoring saints and martyrs (Halloween is short for “All Hallows’ Eve” — “hallow” being another word for “saint”). Originally celebrated in May, Pope Gregory III elected to move All Saints’ Day to November 1 in the mid-eighth century and Halloween moved along with it, forever linking it with the pagan celebration.

The reasons for this move are contested but, either way, it served an important purpose: with Samhain and Halloween now sharing a date, descendants of the ancient Celts began practicing a combination of folk and religious traditions on and around October 31 — and through this fusion, they managed to preserve pagan beliefs and rituals that may have otherwise been lost. It also resulted in something new: the superstition that the doors to the Otherworld are thrown open on Samhain got mixed in with the prayers for the dead on and around All Saints’ Day, becoming a single belief — that the spirits of the dead return on that day.”

Certainly, the Pope didn’t intend to popularize supernatural beliefs or their accompanying rituals. But ultimately, the people practising a tradition determine whether it lives or dies — not the church or any other authority.

Suffice to say, the “why” behind Halloween is complicated.