Teachers' Page:

We start each week with a Monday Morning Meeting for staff. It's a time for information sharing, celebrating staff and children's achievements, laughter, building and strengthening the kaupapa foundations for our school, and a few tips on teaching, techie skills and even life. This page will be the place teachers can come back to if they want to revisit anything we covered in our Monday Morning Meetings.

It's really a page for teachers, but if you find anything worthwhile here for yourself, great.

Article

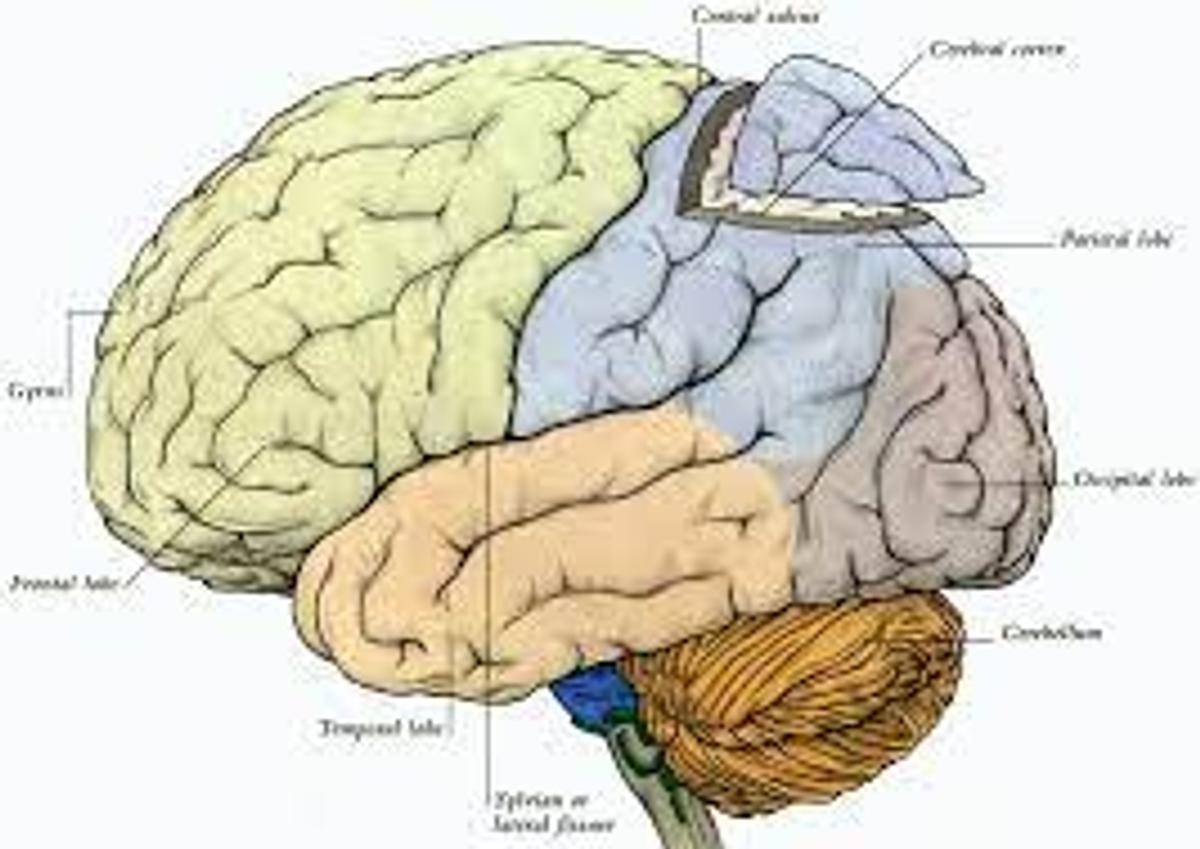

How Do We Learn? Neuroscientists Pinpoint How Memories Are Likely To Be Stored In The Brain:

New work by a team of neuroscientists led by Dr Tomás Ryan from Trinity CollegeDublin shows that learning occurs through continuously forming new connectivity patterns between specific engram cells in different brain regions.

Whether on purpose, incidentally, or simply by accident, we constantly learn, and our brains constantly change. When we navigate the world, interact with others, or consume media content, our brain grasps information, creating new memories.

The next time we walk down the street, meet our friends, or come across something that reminds us of the last podcast we listened to, we will quickly re-engage that memory information somewhere in our brain. But how do these experiences modify our neurons to allow us to form these new memories?

Our brains are organs composed of dynamic networks of cells, always in a state of flux due to growing up, aging, degeneration, regeneration, everyday noise, and learning. The challenge for scientists is to identify the "difference that makes a difference" for forming a memory -- the change in a brain that stores memory is referred to as an engram, which retains information for later use.

This newly published study aimed to understand how information may be stored as engrams in the brain.

Dr Clara Ortega-de San Luis, Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the Ryan Lab and lead author of the article published today in the leading international journal, CurrentBiology, said:

"Memory engram cells are groups of brain cells that, activated by specific experiences, change themselves to incorporate and thereby hold information in our brain. Reactivating these 'building blocks' of memories triggers the recall of the specific associated experiences. The question is, how do engrams store meaningful information about the world?"

To identify and study the changes that engrams undergo that allow us to encode a memory, the team of researchers studied a form of learning in which two similar experiences become linked by the nature of their content.

The researchers used a paradigm in which animals learned to identify different contexts and form associations between them. By using genetic techniques, the team crucially labelled two different populations of engram cells in the brain for two discrete memories. Then, it monitored how learning manifested in forming new connections between those engram cells.

Then, using optogenetics, which allows brain cell activity to be controlled with light, they further demonstrated how these newly formed connections were required for the learning to occur. In doing so, they identified a molecular mechanism mediated by a specific protein in the synapse that regulates the connectivity between engram cells.

This study provides direct evidence for changes in synaptic wiring connectivity between engram cells to be considered as a likely mechanism for memory storage in the brain.

Commenting on the study, Dr Ryan, Associate Professor in Trinity's School ofBiochemistry and Immunology, Trinity Biomedical Sciences Institute, and the TrinityCollege Institute of Neuroscience, said:

"Understanding the cellular mechanisms that allow learning to occur helps us comprehend not only how we form new memories or modify those pre-existent ones, but also advance our knowledge towards disentangling how the brain works and the mechanisms needed to process thoughts and information.

"In 21st-century neuroscience, many of us like to think memories are stored in engram cells or their subcomponents. This study argues that we should search for information between cells rather than within or at cells. Learning may work by altering the brain's wiring diagram—less like a computer and more like a developing sculpture.

"In other words, the engram is not in the cell; the cell is in the engram."

The beginner chases the right answers.

The master chases the right questions.

Web Pages:

https://www.youtube.com/@numberphile/videos

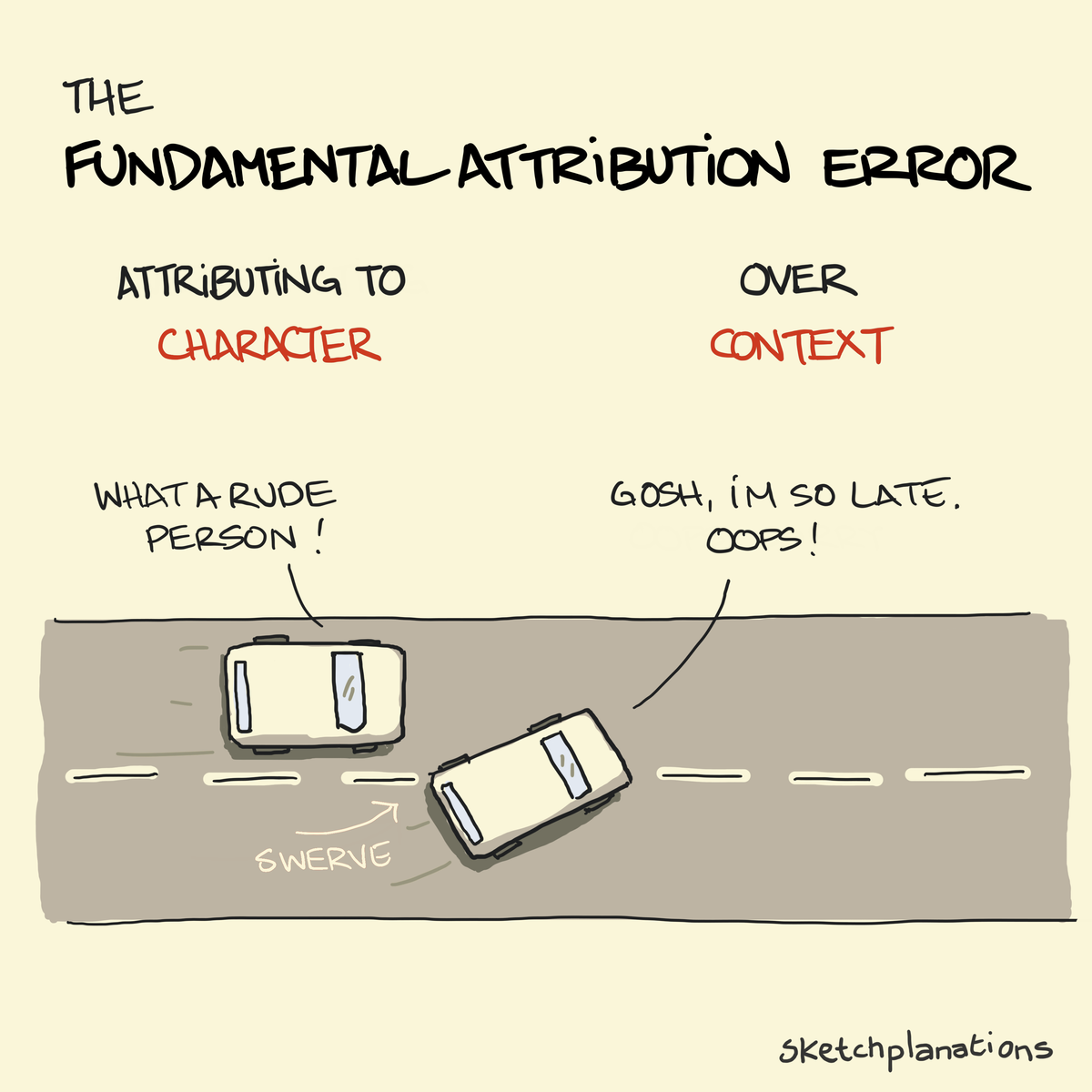

The Fundamental Attribution Error - OR

Not Understanding Context Before Blaming:

The fundamental attribution error is the attribution of the source of behaviour to a person's character and personality above the consideration of context. It's sometimes described as over-attributing causes to disposition over situation.

In a classic example, if a driver swerves in front of you suddenly, it's easy to attribute the cause of the behaviour to the driver being a jerk, i.e. to their character. What we may not see is that the driver is late to pick up their kids, was distracted by a challenging conversation they just had at work, and they're worried they've gone the wrong way and are driving an unfamiliar car.

If a colleague is late to meet us, we might infer that the person is lazy or disrespectful when, in fact, they may have been held up by a traffic accident, been on the phone with a sick relative, and have had trouble sleeping lately. If we are late for a meeting, well, then it's probably for all sorts of good reasons outside our control.

Like confirmation bias, the fundamental attribution error is a big one that can easily colour our interactions with others without us being aware of it.

Some ways to minimise it include:

Remember that what we see is just a tiny fraction of any other person's life and that we don't see the complete picture. Minimise judgment, particularly around character and personality. Avoid jumping to conclusions. Where appropriate, ask if anything is bothering others. Build empathy for others as you would for yourself. Reflect on the positive things others do.

Techie Tips:

⌘+T opens a new tab in Safari. If you’re like me and open dozens of tabs at once for research, you need this.

You don’t always need to press that ⊕ symbol beside tabs. Next time, Try using ‘⌘+T’ for new tabs.

Copy something on your phone - paste it on your Mac - and vice versa.

Copy a file using ⌘ + C (like normal) and then paste it using ⌘ + ⌥ + V - Command + Option + V

This hotkey (⌘+⌥+V) pastes the file to the destination and deletes it from the original location.

Shift+⌘+R (Opens AirDrop menu)

AirDrop is fast, but it can be faster - press ‘Shift+⌘+R’ to open the AirDrop menu, select the recipient, and drop your files to instantly send them.

Control + Command + Space

Show character viewer (emoji and other symbols). This keyboard shortcut allows you to add emojis and other symbols to your documents.

Briefly - New Meaning to Phrase 'Bird Brain':

For most of the twentieth century, psychologists dismissed the interior lives of birds because avian brains are smaller and differently structured than those of mammals. But it turns out that bird brains are much denser with neurons and consume less energy, giving crows similar cognitive abilities to large-brained mammals such as great apes, elephants, and whales.

John Marzluff, an ecologist in Seattle, once wore a rubber caveman mask while catching and releasing seven crows on his university campus; eighteen years later, crows that weren’t alive for the original experiment still caw at the mask. “I really didn’t know they were paying that much attention to me,” Marzluff told me recently. His study showed that crows retain long-term memories, learn from their peers, and pass behaviours from generation to generation.

Other experiments have shown that members of the corvid family, which includes crows, jays, and magpies, can read one another’s intentions, plan for the future, and solve puzzles using abstract reasoning and tools.

To Ponder:

Always say less than necessary. Saying less than necessary and not interjecting at every chance we get is actually the mark of a self-disciplined, smart, and wise person.

Sketchplanations

The upward spiral is Stephen R. Covey's simple model of personal growth and change, which repeats the three steps: Learn, Commit, and Do.

Of course, we are all doing it all of the time. The difference is taking the time and effort to learn from our doing, deciding to commit to how we want to grow, and deliberately putting it into action. Getting better is in our control.

Though it didn't seem like it would take any effort, I've found the commit step to be surprisingly important. Repeating each of the three steps again and again is a simple and guaranteed path to improving at anything we try.

Stephen Covey discusses the upward spiral as part of sharpening the saw—renewing, refreshing and recharging ourselves to be the best we can be:

"Renewal is the principle—and the process—that empowers us to move on an upward spiral of growth and change, of continuous improvement."

— Dr Stephen R. Covey

May you all be spiralling upwards.

If Human History Was a 1,000 Page Book:

Humans have been around for a long, long time - between 200,000 and 300,000 years. If we made a book about humans called The Story of Us, and each single page covered 250 years of history, the book would be about 1,000 pages long. To take a closer look, let's tear all the pages out and lay them on the table:

My whole lifetime is the last paragraph on the last page of this book.

When I try to undo 999 and three-quarter pages of history, it’s going to be hard.

The Ultimate Productivity Hack is Saying No

Not doing something will always be faster than doing it. This statement reminds me of the old computer programming saying, “Remember that there is no code faster than no code.”

The same philosophy applies in other areas of life. For example, no meeting goes faster than not having a meeting at all.

This is not to say you should never attend another meeting, but the truth is that we say yes to many things we don’t actually want to do. Many meetings are held that don’t need to be held, and a lot of code is written that could be deleted.

How often do people ask you to do something, and you just reply, “Sure thing.” Three days later, you’re overwhelmed by how much is on your to-do list. We become frustrated by our obligations even though we were the ones who said yes to them in the first place.

It’s worth asking if things are necessary. Many of them are not, and a simple “no” will be more productive than whatever work the most efficient person can muster.

But if the benefits of saying no are so obvious, then why do we say yes so often?

Why We Say Yes

We agree to many requests not because we want to do them but because we don’t want to be seen as rude, arrogant, or unhelpful. Often, you have to consider saying no to someone you will interact with again in the future—your co-worker, your spouse, your family and friends. Saying no to these people can be particularly difficult because we like them and want to support them.

(We often need their help, too.) Collaborating with others is an important element of life.

The thought of straining the relationship outweighs our time and energy commitment.

For this reason, being gracious in your response can be helpful. Do whatever favours you can, and be warm-hearted and direct when you have to say no.

But even after we have accounted for these social considerations, many of us still seem to do a poor job of managing the tradeoff between yes and no. We find ourselves over-committed to things that don’t meaningfully improve or support those around us, and certainly don’t improve our own lives.

Perhaps one issue is how we think about the meaning of yes and no.

The Difference Between Yes and No

The words “yes” and “no” get used in comparison to each other so often that it feels like they carry equal weight in conversation. In reality, they are not just opposite in meaning but of entirely different magnitudes in commitment.

When you say no, you are only saying no to one option. When you say yes, you are saying no to every other option.

I like how the economist Tim Harford put it, “Every time we say yes to a request, we are also saying no to anything else we might accomplish with the time.”

Once you have committed to something, you have already decided how that future block of time will be spent. In other words, saying no saves you time in the future. Saying yes costs you time in the future.

No is a form of time credit. You retain the ability to spend your future time however you want.

Yes is a form oftime debt. You have to pay back your commitment at some point.

No is a decision. Yes is a responsibility.

The Role of No

Saying no is sometimes seen as a luxury that only those in power can afford. And it is true: turning down opportunities is easier when you can fall back on the safety net provided by power, money, and authority.

But it is also true that saying no is not merely a privilege reserved for the successful among us. It is also a strategy that can help you become successful.

Saying no is an important skill to develop at any stage of your career because it retains the most important asset in life: your time. As the investor Pedro Sorrentino put it, “If you don’t guard your time, people will steal it from you.”

You need to say no to whatever isn’t leading you toward your goals, including distractions.

As one reader told me, “If you broaden the definition of how you apply no, it actually is the only productivity hack (as you ultimately say no to any distraction to be productive).”

Nobody embodied this idea better than Steve Jobs, who said, “People think focus means saying yes to the thing you’ve got to focus on. But that’s not what it means at all. It means saying no to the hundred other good ideas that there are. You have to pick carefully.”

There is an important balance to strike here. Saying no doesn’t mean you’ll never do anything interesting, innovative or spontaneous. It just means that you say yes in a focused way. Once you have knocked out the distractions, it can make sense to say yes to any opportunity that could potentially move you in the right direction. You may have to try many things to discover what works and what you enjoy.

This exploration period can be particularly important at the beginning of a project, job, or career.

Upgrading Your No

Over time, as you continue to improve and succeed, your strategy needs to change.

The opportunity cost of your time increases as you become more successful. At first, you just eliminate the obvious distractions and explore the rest. As your skills improve and you learn to separate what works from what doesn’t, you must continually increase your threshold for saying yes.

You still need to say no to distractions, but you also need to learn to say no to opportunities that were previously good uses of time to make space for great uses of time. It’s a good problem to have, but it can be a tough skill to master.

In other words, you must upgrade your “no’s” over time.

Upgrading your no doesn’t mean you’ll never say yes. It means you default to saying no and only saying yes when it makes sense.

To quote the investor Brent Beshore, “Saying no is so powerful because it preserves the opportunity to say yes.”

The general trend seems to be something like this: If you can learn to say no to bad distractions, you’ll eventually earn the right to say no to good opportunities.

How to Say No

Most of us are probably too quick to say yes or too slow to say no. It’s worth asking yourself where you fall on that spectrum.

If you have trouble saying no, you may find the following strategy proposed by Tim Harford, the British economist I mentioned earlier, to be helpful. He writes, “One trick is to ask, “If I had to do this today, would I agree to it?”

It’s not a bad rule of thumb since any future commitment, no matter how far away it might

be, will eventually become an imminent problem.”

If an opportunity is exciting enough to drop whatever you’re doing right now, it’s a yes. If it’s not, then perhaps you should think twice.

This is similar to Derek Sivers's well-known “Hell Yeah or No” method. If someone asks you to do something and your first reaction is “Hell Yeah!” Do it. If it doesn’t excite you, say no.

It’s impossible to remember to ask yourself these questions each time you face a decision, but it’s still a useful exercise to revisit from time to time. Saying no can be difficult, but it is often easier than the alternative. As writer Mike Dariano pointed out, “It’s easier to avoid commitments than get out of them. Saying no keeps you toward the easier end of this spectrum.”

What is true about health is also true about productivity: an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

The Power of No

More effort is wasted doing things that don’t matter than is wasted doing things inefficiently. If that is the case, elimination is a more useful skill than optimization.

I am reminded of the famous Peter Drucker quote, “There is nothing so useless as doing efficiently that which should not be done at all.”

About the Author

James Clear writes about habits, decision-making, and continuous improvement. He is the author of the #1 New York Times bestseller, Atomic Habits. The book has sold over 15 million copies worldwide and has been translated into more than 50 languages.