Solar Eclipse:

Solar Eclipse Explained + Photos:

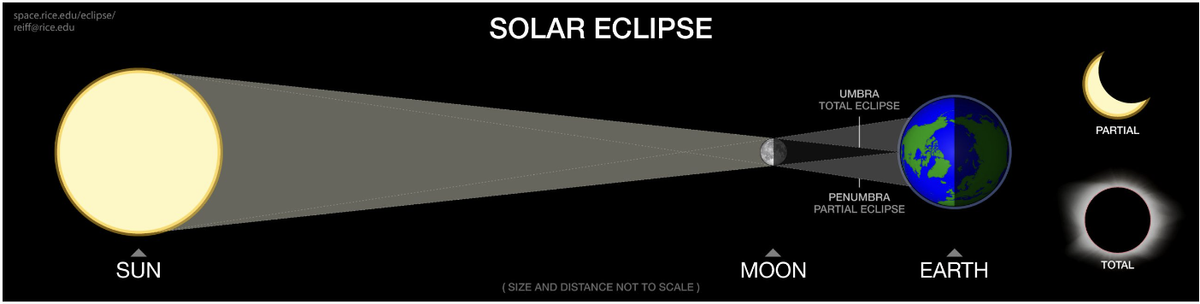

Solar eclipses happen when the moon passes directly through the invisible line connecting the sun and Earth, something that doesn’t happen very often because space is big and the invisible line is skinny. Here’s a very not-to-scale diagram (to make it to scale, picture the sun being a basketball on one side of the basketball court, the Earth being a 2mm-diameter pebble on the other side of the court, and the moon being a small grain of sand about 7cm away from the pebble).

Earthlings are very lucky, eclipse-wise. Most planets don’t have a big enough moon to create a total solar eclipse. Not only is our moon big enough, but it’s about exactly the size of the sun in our night sky because, by sheer coincidence, the sun is about 400 times farther from us than the moon and also about 400 times bigger than the moon in diameter—making our eclipses especially breathtaking.

Incredible “tiny planet” panorama timelapse by Matt Biddulph.

One Writer's Experience of Totality:

We ended up in a big open rural field that may or may not have been part of someone’s farm. It was us and some cows. The sky was perfectly clear.

30 minutes until totality. I looked through my glasses at a crescent sun. It seemed a little dimmer out than usual, but only a little.

20 minutes. Thinner crescent, a tad dimmer, maybe a tad cooler than before?

10 minutes. Razor-thin crescent now, definitely weird lighting. Because all the light comes from one small area, shadows are very sharp. You can see the shadow of individual hairs on your head.

1 minute. It’s very dim, like early evening, but still feels like daytime generally. Waves of light and dark ripple across the ground, like how light moves at the bottom of a swimming pool.

5 seconds. Diamond ring! I take off my glasses, and the diamond ring looks strikingly beautiful and strange.

4, 3, 2, 1. The Earth’s dimmer switch suddenly goes downnnnn as dim daylight drops into night.

Totality.

Imagine a world where there was always cloud cover, and one day every few years, in certain places, the sky cleared at night, and you could see stars for the first time in your life. It would be a totally surreal experience, something that reminded you that you don’t live in a big world but on the edge of a tiny rock in vast outer space. It would show you the truth about reality.

We see stars all the time, so we’re well-acquainted with our reality of living in outer space (even if it’s easy to forget during the day). But when I looked up at the sky during the total eclipse, it was the first time I had experienced another, totally different way to see with my eyes that I lived in outer space. I saw one sphere positioned in front of another sphere, with two other spheres—Venus and Jupiter—floating nearby. More than ever before, it felt obvious that I was standing on the edge of a fifth sphere. For the first time in my life, I was looking at the Solar System.

I looked around. It was dark. At 2 p.m., there was a 360° sunset along the entire horizon—another first. By a minute in, there was a chorus of chirping crickets that hadn’t been there before. Birds were flying around overhead that hadn’t been there before. The cows continued being cows, but I assume they were super confused.

Shot from Rami Ammoun…it’s a blend of multiple exposures so you can see the sun and moon at the same time.

Cool Video of the Four Minutes of Totality:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zD9ryv_QhpY&t=1s

Techie Tips:

⌘+T opens a new tab in Safari. If you’re like me and open dozens of tabs at once for research, you need this.

You don’t always need to press that ⊕ symbol beside tabs. Next time, Try using ‘⌘+T’ for new tabs.

Copy something on your phone - paste it on your Mac - and vice versa.

Copy a file using ⌘ + C (like normal) and then paste it using ⌘ + ⌥ + V - Command + Option + V

This hotkey (⌘+⌥+V) pastes the file to the destination and deletes it from the original location.

Shift+⌘+R (Opens AirDrop menu)

AirDrop is fast, but it can be faster - press ‘Shift+⌘+R’ to open the AirDrop menu, select the recipient, and drop your files to instantly send them.

Control + Command + Space

Show character viewer (emoji and other symbols). This keyboard shortcut allows you to add emojis and other symbols to your documents.

Briefly - New Meaning to Phrase 'Bird Brain':

For most of the twentieth century, psychologists dismissed the interior lives of birds because avian brains are smaller and differently structured than those of mammals. But it turns out that bird brains are much denser with neurons and consume less energy, giving crows similar cognitive abilities to large-brained mammals such as great apes, elephants, and whales.

John Marzluff, an ecologist in Seattle, once wore a rubber caveman mask while catching and releasing seven crows on his university campus; eighteen years later, crows that weren’t alive for the original experiment still caw at the mask. “I really didn’t know they were paying that much attention to me,” Marzluff told me recently. His study showed that crows retain long-term memories, learn from their peers, and pass behaviours from generation to generation.

Other experiments have shown that members of the corvid family, which includes crows, jays, and magpies, can read one another’s intentions, plan for the future, and solve puzzles using abstract reasoning and tools.

To Ponder:

Always say less than necessary. Saying less than necessary and not interjecting at every chance we get is actually the mark of a self-disciplined, smart, and wise person.

Sketchplanations

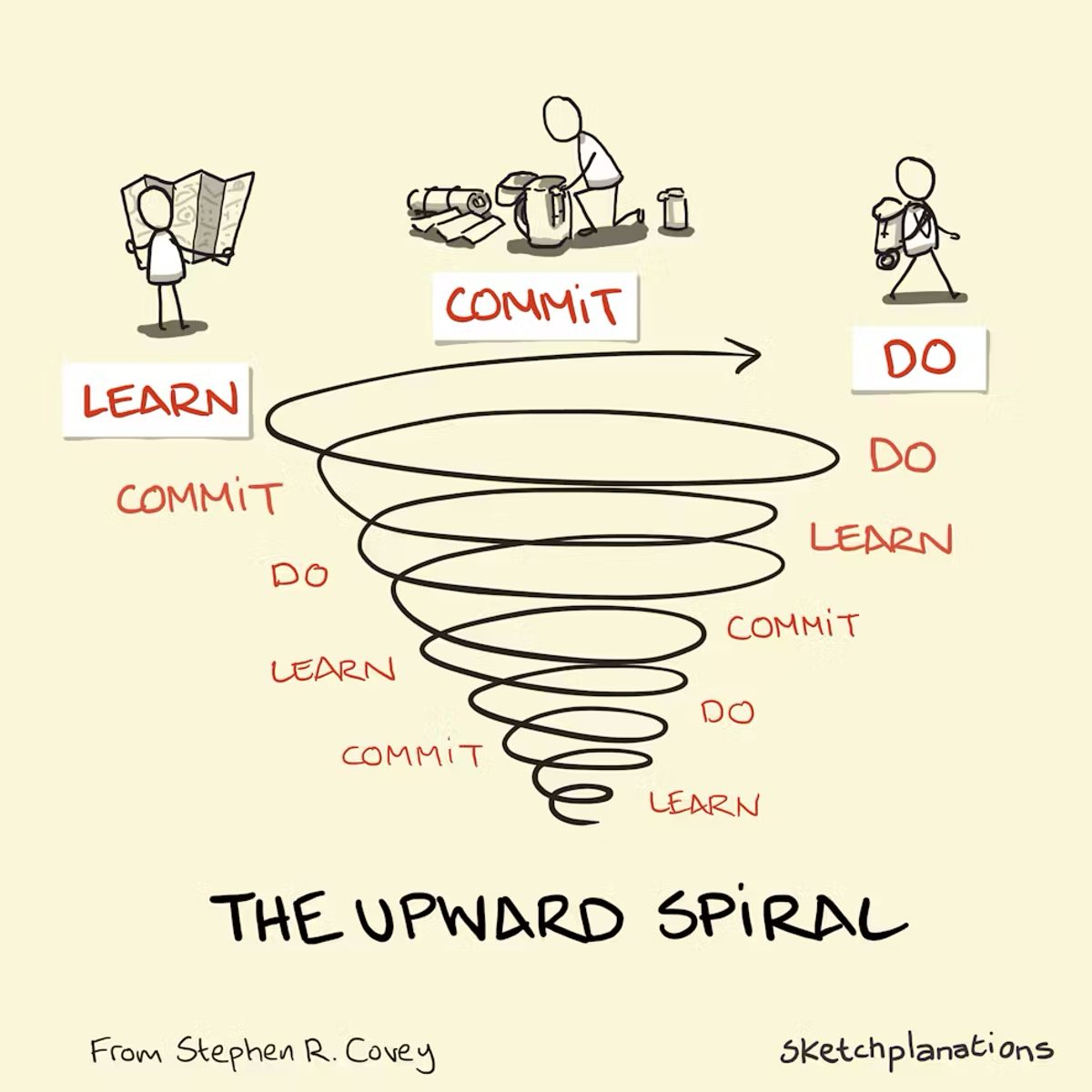

The upward spiral is Stephen R. Covey's simple model of personal growth and change, which repeats the three steps: Learn, Commit, and Do.

Of course, we are all doing it all of the time. The difference is taking the time and effort to learn from our doing, deciding to commit to how we want to grow, and deliberately putting it into action. Getting better is in our control.

Though it didn't seem like it would take any effort, I've found the commit step to be surprisingly important. Repeating each of the three steps again and again is a simple and guaranteed path to improving at anything we try.

Stephen Covey discusses the upward spiral as part of sharpening the saw—renewing, refreshing and recharging ourselves to be the best we can be:

"Renewal is the principle—and the process—that empowers us to move on an upward spiral of growth and change, of continuous improvement."

— Dr Stephen R. Covey

May you all be spiralling upwards.

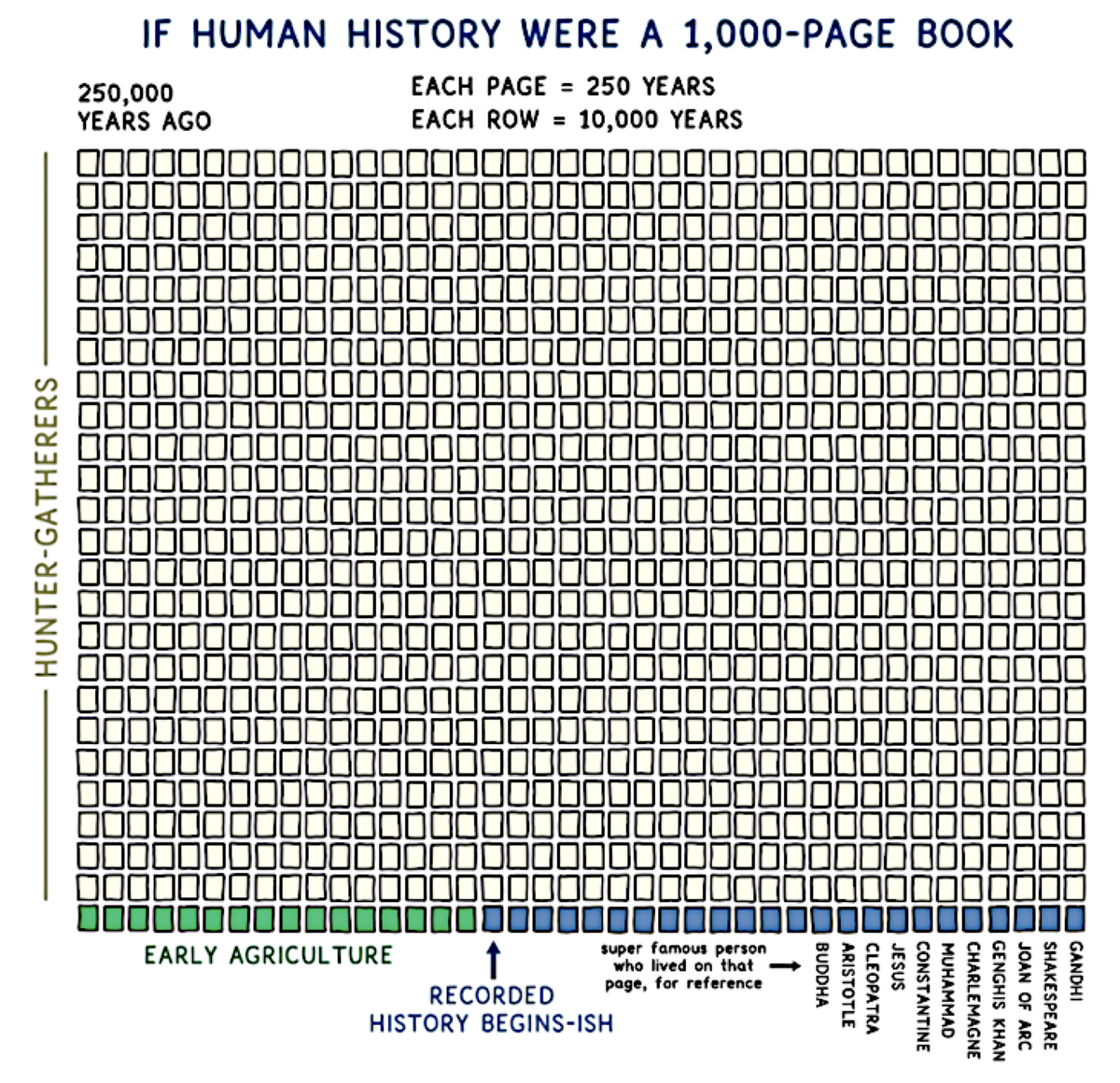

If Human History Was a 1,000 Page Book:

Humans have been around for a long, long time - between 200,000 and 300,000 years. If we made a book about humans called The Story of Us, and each single page covered 250 years of history, the book would be about 1,000 pages long. To take a closer look, let's tear all the pages out and lay them on the table:

My whole lifetime is the last paragraph on the last page of this book.

When I try to undo 999 and three-quarter pages of history, it’s going to be hard.

The Ultimate Productivity Hack is Saying No

Not doing something will always be faster than doing it. This statement reminds me of the old computer programming saying, “Remember that there is no code faster than no code.”

The same philosophy applies in other areas of life. For example, no meeting goes faster than not having a meeting at all.

This is not to say you should never attend another meeting, but the truth is that we say yes to many things we don’t actually want to do. Many meetings are held that don’t need to be held, and a lot of code is written that could be deleted.

How often do people ask you to do something, and you just reply, “Sure thing.” Three days later, you’re overwhelmed by how much is on your to-do list. We become frustrated by our obligations even though we were the ones who said yes to them in the first place.

It’s worth asking if things are necessary. Many of them are not, and a simple “no” will be more productive than whatever work the most efficient person can muster.

But if the benefits of saying no are so obvious, then why do we say yes so often?

Why We Say Yes

We agree to many requests not because we want to do them but because we don’t want to be seen as rude, arrogant, or unhelpful. Often, you have to consider saying no to someone you will interact with again in the future—your co-worker, your spouse, your family and friends. Saying no to these people can be particularly difficult because we like them and want to support them.

(We often need their help, too.) Collaborating with others is an important element of life.

The thought of straining the relationship outweighs our time and energy commitment.

For this reason, being gracious in your response can be helpful. Do whatever favours you can, and be warm-hearted and direct when you have to say no.

But even after we have accounted for these social considerations, many of us still seem to do a poor job of managing the tradeoff between yes and no. We find ourselves over-committed to things that don’t meaningfully improve or support those around us, and certainly don’t improve our own lives.

Perhaps one issue is how we think about the meaning of yes and no.

The Difference Between Yes and No

The words “yes” and “no” get used in comparison to each other so often that it feels like they carry equal weight in conversation. In reality, they are not just opposite in meaning but of entirely different magnitudes in commitment.

When you say no, you are only saying no to one option. When you say yes, you are saying no to every other option.

I like how the economist Tim Harford put it, “Every time we say yes to a request, we are also saying no to anything else we might accomplish with the time.”

Once you have committed to something, you have already decided how that future block of time will be spent. In other words, saying no saves you time in the future. Saying yes costs you time in the future.

No is a form of time credit. You retain the ability to spend your future time however you want.

Yes is a form oftime debt. You have to pay back your commitment at some point.

No is a decision. Yes is a responsibility.

The Role of No

Saying no is sometimes seen as a luxury that only those in power can afford. And it is true: turning down opportunities is easier when you can fall back on the safety net provided by power, money, and authority.

But it is also true that saying no is not merely a privilege reserved for the successful among us. It is also a strategy that can help you become successful.

Saying no is an important skill to develop at any stage of your career because it retains the most important asset in life: your time. As the investor Pedro Sorrentino put it, “If you don’t guard your time, people will steal it from you.”

You need to say no to whatever isn’t leading you toward your goals, including distractions.

As one reader told me, “If you broaden the definition of how you apply no, it actually is the only productivity hack (as you ultimately say no to any distraction to be productive).”

Nobody embodied this idea better than Steve Jobs, who said, “People think focus means saying yes to the thing you’ve got to focus on. But that’s not what it means at all. It means saying no to the hundred other good ideas that there are. You have to pick carefully.”

There is an important balance to strike here. Saying no doesn’t mean you’ll never do anything interesting, innovative or spontaneous. It just means that you say yes in a focused way. Once you have knocked out the distractions, it can make sense to say yes to any opportunity that could potentially move you in the right direction. You may have to try many things to discover what works and what you enjoy.

This exploration period can be particularly important at the beginning of a project, job, or career.

Upgrading Your No

Over time, as you continue to improve and succeed, your strategy needs to change.

The opportunity cost of your time increases as you become more successful. At first, you just eliminate the obvious distractions and explore the rest. As your skills improve and you learn to separate what works from what doesn’t, you must continually increase your threshold for saying yes.

You still need to say no to distractions, but you also need to learn to say no to opportunities that were previously good uses of time to make space for great uses of time. It’s a good problem to have, but it can be a tough skill to master.

In other words, you must upgrade your “no’s” over time.

Upgrading your no doesn’t mean you’ll never say yes. It means you default to saying no and only saying yes when it makes sense.

To quote the investor Brent Beshore, “Saying no is so powerful because it preserves the opportunity to say yes.”

The general trend seems to be something like this: If you can learn to say no to bad distractions, you’ll eventually earn the right to say no to good opportunities.

How to Say No

Most of us are probably too quick to say yes or too slow to say no. It’s worth asking yourself where you fall on that spectrum.

If you have trouble saying no, you may find the following strategy proposed by Tim Harford, the British economist I mentioned earlier, to be helpful. He writes, “One trick is to ask, “If I had to do this today, would I agree to it?”

It’s not a bad rule of thumb since any future commitment, no matter how far away it might

be, will eventually become an imminent problem.”

If an opportunity is exciting enough to drop whatever you’re doing right now, it’s a yes. If it’s not, then perhaps you should think twice.

This is similar to Derek Sivers's well-known “Hell Yeah or No” method. If someone asks you to do something and your first reaction is “Hell Yeah!” Do it. If it doesn’t excite you, say no.

It’s impossible to remember to ask yourself these questions each time you face a decision, but it’s still a useful exercise to revisit from time to time. Saying no can be difficult, but it is often easier than the alternative. As writer Mike Dariano pointed out, “It’s easier to avoid commitments than get out of them. Saying no keeps you toward the easier end of this spectrum.”

What is true about health is also true about productivity: an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

The Power of No

More effort is wasted doing things that don’t matter than is wasted doing things inefficiently. If that is the case, elimination is a more useful skill than optimization.

I am reminded of the famous Peter Drucker quote, “There is nothing so useless as doing efficiently that which should not be done at all.”

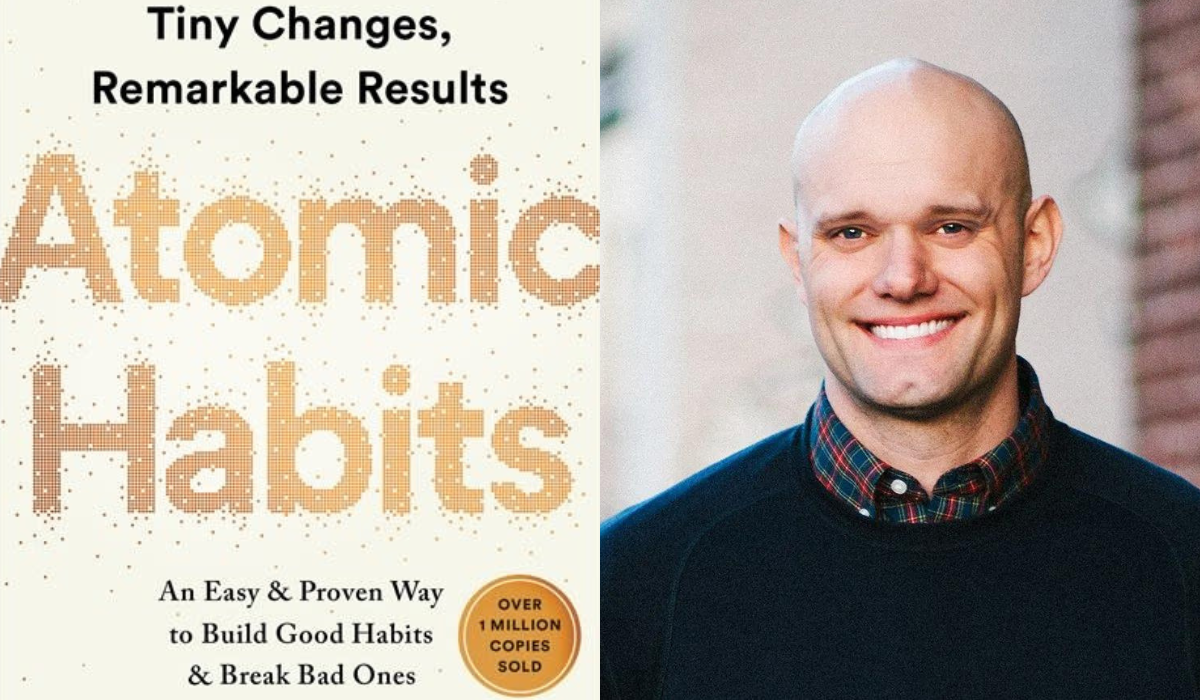

About the Author

James Clear writes about habits, decision-making, and continuous improvement. He is the author of the #1 New York Times bestseller, Atomic Habits. The book has sold over 15 million copies worldwide and has been translated into more than 50 languages.