Mental Health in Primary Schools (MHiPS)

Amy Carter

Mental Health in Primary Schools (MHiPS)

Amy Carter

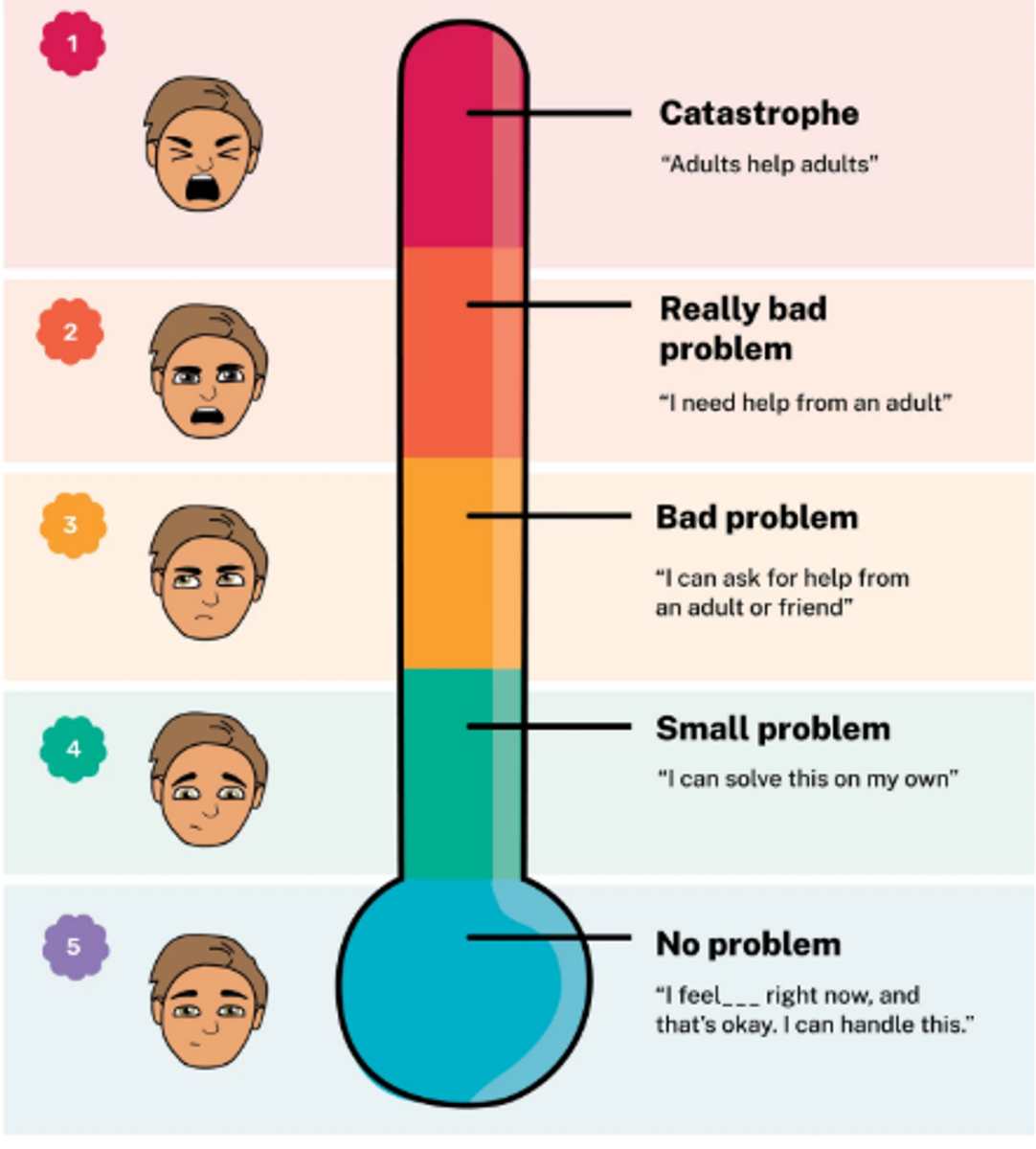

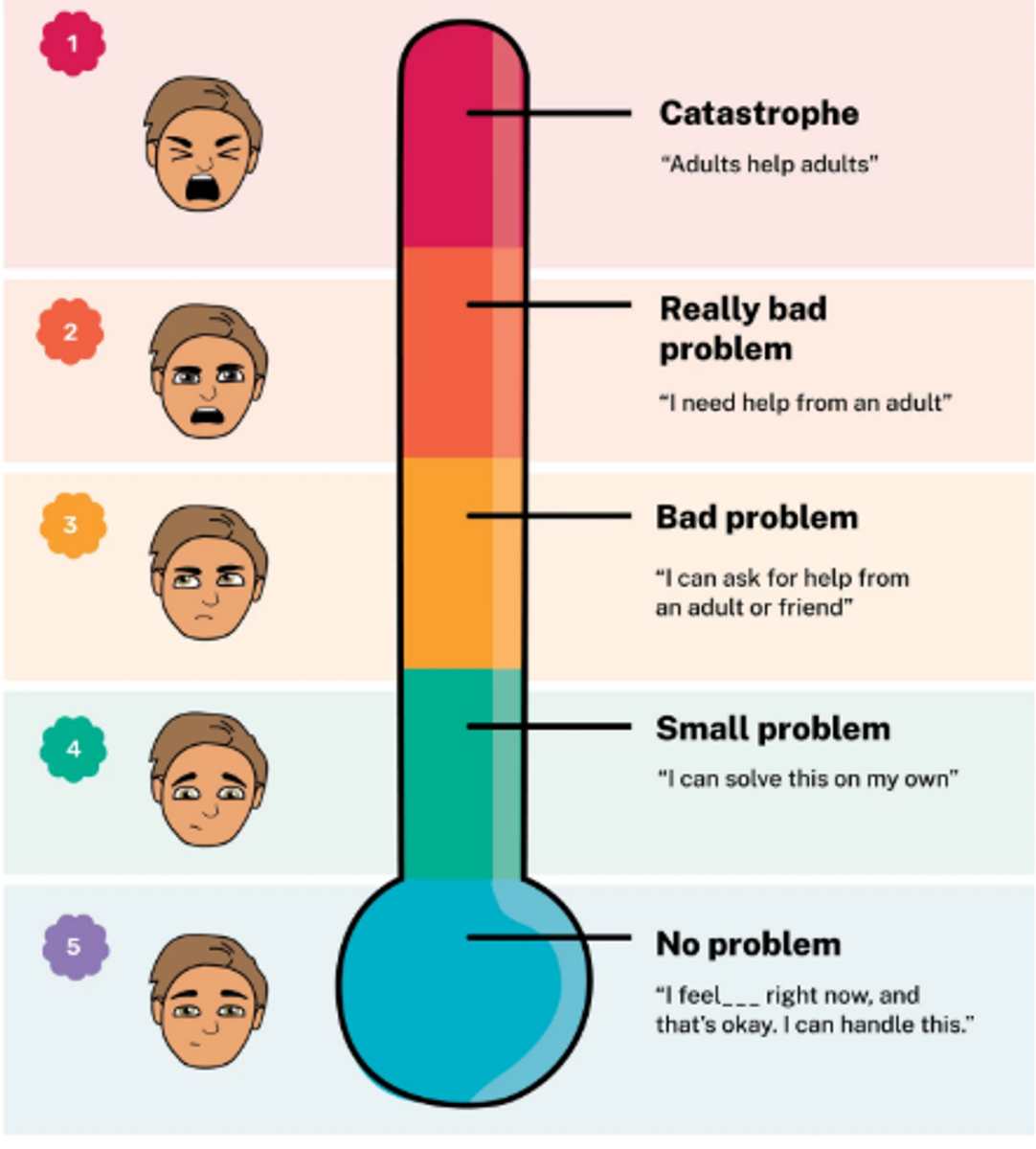

This week in The Resilience Project Lessons, students in Year 5 explored Emotional Literacy, looking specifically at The Catastrophe Scale.

The Catastrophe Scale is a tool used to help individuals, particularly children, assess the severity of problems or emotional reactions. It encourages perspective-taking by rating situations on a scale where 5 represents a minor issue and 1 signifies a major catastrophe.

The scale used in this lesson can be found below, with an explanation of each stage and the strategies taught to students.

‘Adults help adults’ is the phrase used as if there was a fire in the school, staff would call for emergency services to alert fire and rescue services to put out the fire and assist members of the school community.

‘I need help from an adult’ is the phrase used as we can seek out a trusted adult, such as a teacher or school counsellor, to report the problem to and ask for assistance and support.

‘I can ask for help from an adult or friend’ is the phrase used to decide whether to ask for help from an adult, such as a teacher or counsellor, or to seek support from a friend. This encourages problem-solving skills and seeking appropriate support.

4. Small problem - ‘I can solve this on my own’:

‘I can solve this on my own’ is the phrase used, as we can use problem-solving skills to handle the situation on our own. This fosters independence and resilience.

5. No problem - ‘I feel ____ right now, and that’s okay. I can handle this’:

Anxiety is the feeling of worry or fear that something bad is going to happen. It’s also the physical reactions that go with the feeling, like ‘butterflies in the stomach’. And its behaviour is like avoiding what’s causing the anxiety or wanting a lot of reassurance.

Anxiety, worry and fear are natural emotions.

It’s common for children to feel anxious, worried or afraid. In most cases, these feelings come and go and don’t last long. In fact, different anxieties, fears and worries often develop at different stages of development.

Babies and toddlers are often anxious about separation from you. They also fear things like loud noises, heights and strangers. But babies and toddlers don’t tend to worry in the way that older children do.

Preschoolers might start to show fear of being on their own and of the dark. But worry still isn’t common in this age group. If preschoolers do worry, it tends to be about things like getting sick or hurt.

School-age children might be afraid of supernatural things like ghosts, social situations, criticism, tests and physical harm or threat. Children over 8 years of age might worry about things like failure at sport or school, war, pandemics, the environment and family relationships.

If you think your child is showing signs of typical childhood anxiety, worries or fears, you can support them in several ways:

Most children have fears or worries of some kind. But if you’re concerned about your child’s fears, worries or anxiety, it’s a good idea to seek professional help.

Here’s when to see your GP or another health professional:

Severe anxiety can affect children’s health and happiness. Some anxious children will grow out of their fears, but others will keep having trouble with anxiety unless they get professional help. When children’s anxiety affects their lives and is severe or long-lasting, it might be an anxiety disorder.

These are the most common types of anxiety disorders in children:

You can be a role model for your child by managing your own anxiety. You can also help your child see that anxiety in itself isn’t bad. It’s only a problem when it stops us from doing what we want or need to do.

Children with anxiety disorders and other mental health problems usually respond very well to professional treatment.

You can seek professional information and advice from several sources, including:

Anxiety is a common experience, especially in early childhood. However, when it becomes persistent and interferes with daily life, it may indicate a disorder that requires attention. With appropriate treatment and support, individuals can learn to manage their anxiety and lead fulfilling lives.

If your child is experiencing anxiety and you need support from the school, please don't hesitate to reach out to the Wellbeing Team. We will work together to help you.

Take care and have a wonderful, restful weekend.

Amy Carter