Student Wellbeing: Regulating Emotions

At St Joseph's, we are committed to the holistic development of our students, which includes nurturing their emotional well-being alongside academic growth. Our dedicated teachers conduct explicit lessons focused on helping children recognise and respond to their emotions, particularly when they feel dysregulated.

Led by Rianne Coldebella, our Student Wellbeing Leader, teachers have designed lessons that explicitly teach students how to identify and respond to their emotions. The importance of a consistent, whole-school approach cannot be undervalued.

Using consistent language around the 'zones' of regulation provides our students with a shared understanding and vocabulary to express themselves effectively.

At St Joseph's, our approach is grounded in the latest educational research, ensuring that our methods are both effective and evidence-based. We teach students about the four different zones of regulation at an age-appropriate level:

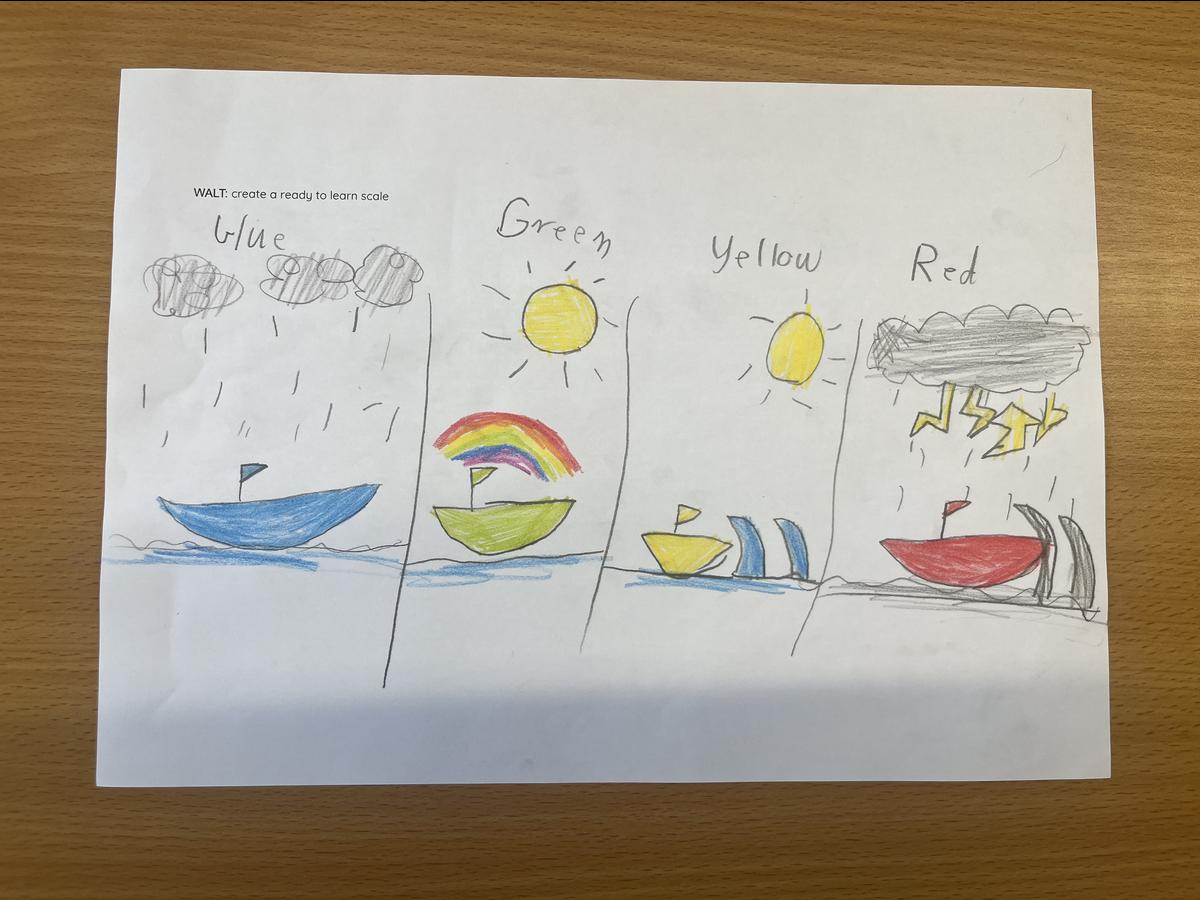

Zones of Regulation

- Blue Zone: sad, tired or sick

- Green Zone: calm, content or focussed

- Yellow Zone: worried, silly or excited

- Red Zone: angry, devastated or terrified

Assigning colours to the zones is a powerful and quick way for students to communicate how they are feeling and the steps they need to take, if any, to prepare themselves for learning.

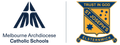

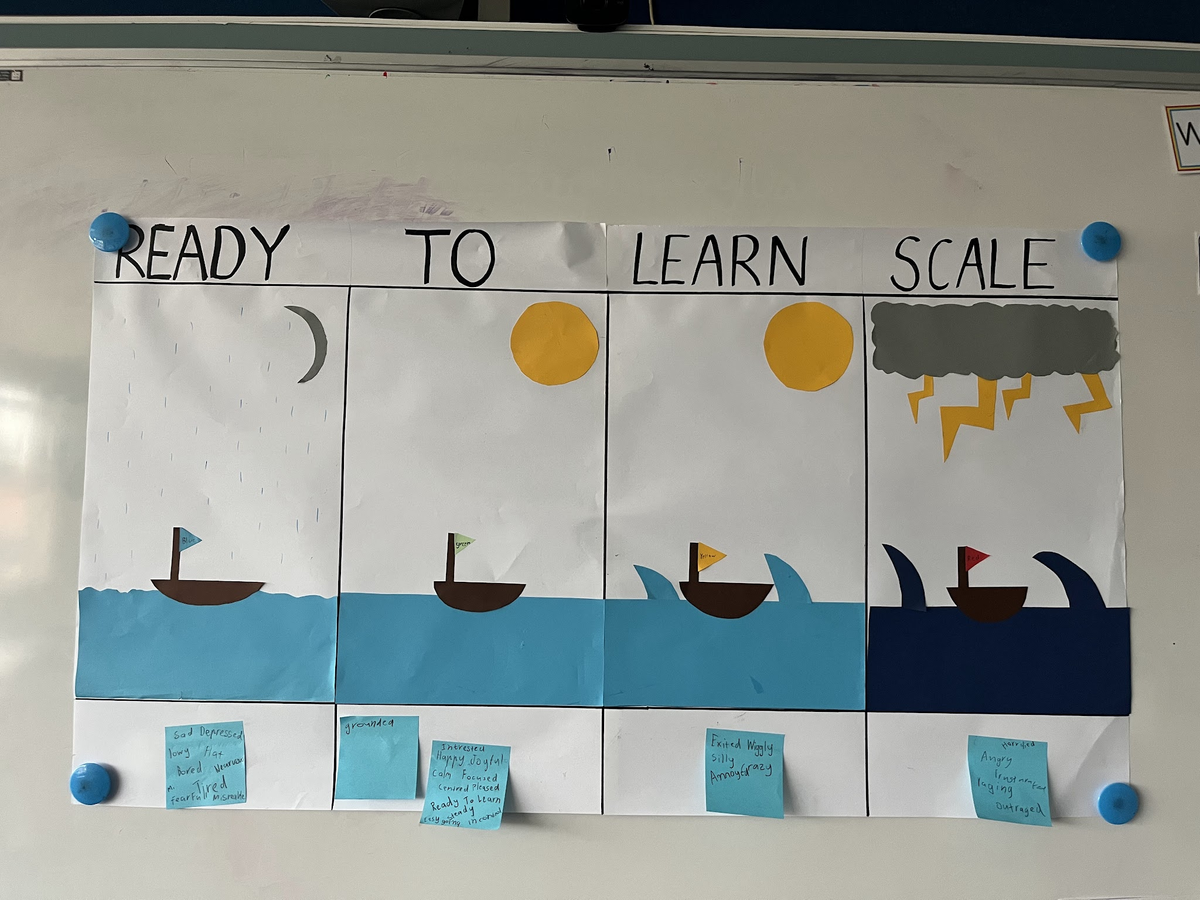

See the photos below for a few examples of 'ready to learn' scales (created by the students) spotted around the school.

We often refer to the 'lid being flipped' when we are in the red zone—dysregulated and so overcome with emotion that we are unable to think or communicate properly. When students reach this zone, the focus shifts to finding a calm and safe space to regulate themselves before engaging in restorative practices or reflecting on the choices they made. We use a common visual of our 'lids being flipped' to communicate to students that we are

not able to think rationally or reasonably in that state.

To learn more about the importance of regulation, please see the article below, published by psychologists Cher McGillvray & Shawna Mastro Campbell of Bond University.

Alannah Harrison

Deputy Principal

Parents are increasingly saying their child is ‘dysregulated’. What does that actually mean?

Published: 30 May, 2024

Cher McGillvray & Shawna Mastro Campbell

Welcome aboard the roller coaster of parenthood, where emotions run wild, tantrums reign supreme and love flows deep.

As children reach toddlerhood and beyond, parents adapt to manage their child’s big emotions and meltdowns. Parenting terminology has adapted too, with more parents describing their child as “dysregulated”. But what does this actually mean?

More than an emotion

Emotional dysregulation refers to challenges a child faces in recognising and expressing emotions, and managing emotional reactions in social settings. This may involve either suppressing emotions or displaying exaggerated and intense emotional responses that get in the way of the child doing what they want or need to do.

“Dysregulation” is more than just feeling an emotion. An emotion is a signal, or cue, that can give us important insights to ourselves and our preferences, desires and goals.

An emotionally dysregulated brain is overwhelmed and overloaded (often, with distressing emotions like frustration, disappointment and fear) and is ready to fight, flight or freeze.

Developing emotional regulation

Emotion regulation is a skill that develops across childhood and is influenced by factors such as the child’s temperament and the emotional environment in which they are raised. It’s typical for children to experience emotional dysregulation when their initiatives are thwarted or criticised, leading to occasional tantrums or outbursts.

A typically developing child will see these types of outbursts reduce as their cognitive abilities become more sophisticated, usually around the age they start school.

Express, don’t suppress

Expressing emotions in childhood is crucial for social and emotional development. It involves the ability to convey feelings verbally and through facial expressions and body language.

When children struggle with emotional expression, it can manifest in various ways, such as difficulty in being understood, flat facial expressions even in emotionally charged situations, challenges in forming close relationships, and indecisiveness. Several factors, including anxiety, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism, giftedness, rigidity and both mild and significant trauma experiences, can contribute to these issues.

Common mistakes parents can make is dismissing emotions, or distracting children away from how they feel. These strategies don’t work and increase feelings of overwhelm. In the long term, they fail to equip children with the skills to identify, express and communicate their emotions, making them vulnerable to future emotional difficulties.

We need to help children move compassionately towards their difficulties, rather than away from them. Parents need to do this for themselves too.

Caregiving and skill modelling

Parents are responsible for creating an emotional climate that facilitates the development of emotion regulation skills. Parents’ own modelling of emotion regulation when they feel distressed. The way they respond to the expression of emotions in their children, contributes to how children understand and regulate their own emotions.

Children are hardwired to be attuned to their caregivers’ emotions, moods, and coping as this is integral to their survival. In fact, their biggest threat to a child is their caregiver not being OK.

A dysregulated brain and body

When kids enter “fight or flight” mode, they often struggle to cope or listen to reason. When children experience acute stress, they may respond instinctively without pausing to consider strategies or logic.

If your child is in fight mode, you might observe behaviours such as crying , clenching fists or jaw, kicking, punching, biting, swearing, spitting or screaming.

In flight mode, they may appear restless, have darting eyes, exhibit excessive fidgeting, breathe rapidly, or try to run away. A shut-down response may look like fainting or a panic attack. When a child feels threatened, their brain’s frontal lobe, responsible for rational thinking and problem-solving, essentially goes offline.

The amygdala, shown here in red, triggers survival mode. This happens when the amygdala, the brain’s alarm system, sends out a false alarm, triggering the survival instinct. In this state, a child may not be able to access higher functions like reasoning or decision-making.

While our instinct might be to immediately fix the problem, staying present with our child during these moments is more effective. It’s about providing support and understanding until they feel safe enough to engage their higher brain functions again. Reframe your thinking so you see your child as having a problem – not being the problem.

Tips for parents

Take turns discussing the highs and lows of the day at meal times. This is a chance for you to be curious, acknowledge and label feelings, and model that you, too, experience a range of emotions that require you to put into practice skills to cope and has shown evidence in numerous physical, social-emotional, academic and behavioural benefits.