Teaching & Learning Page:

Web Pages:

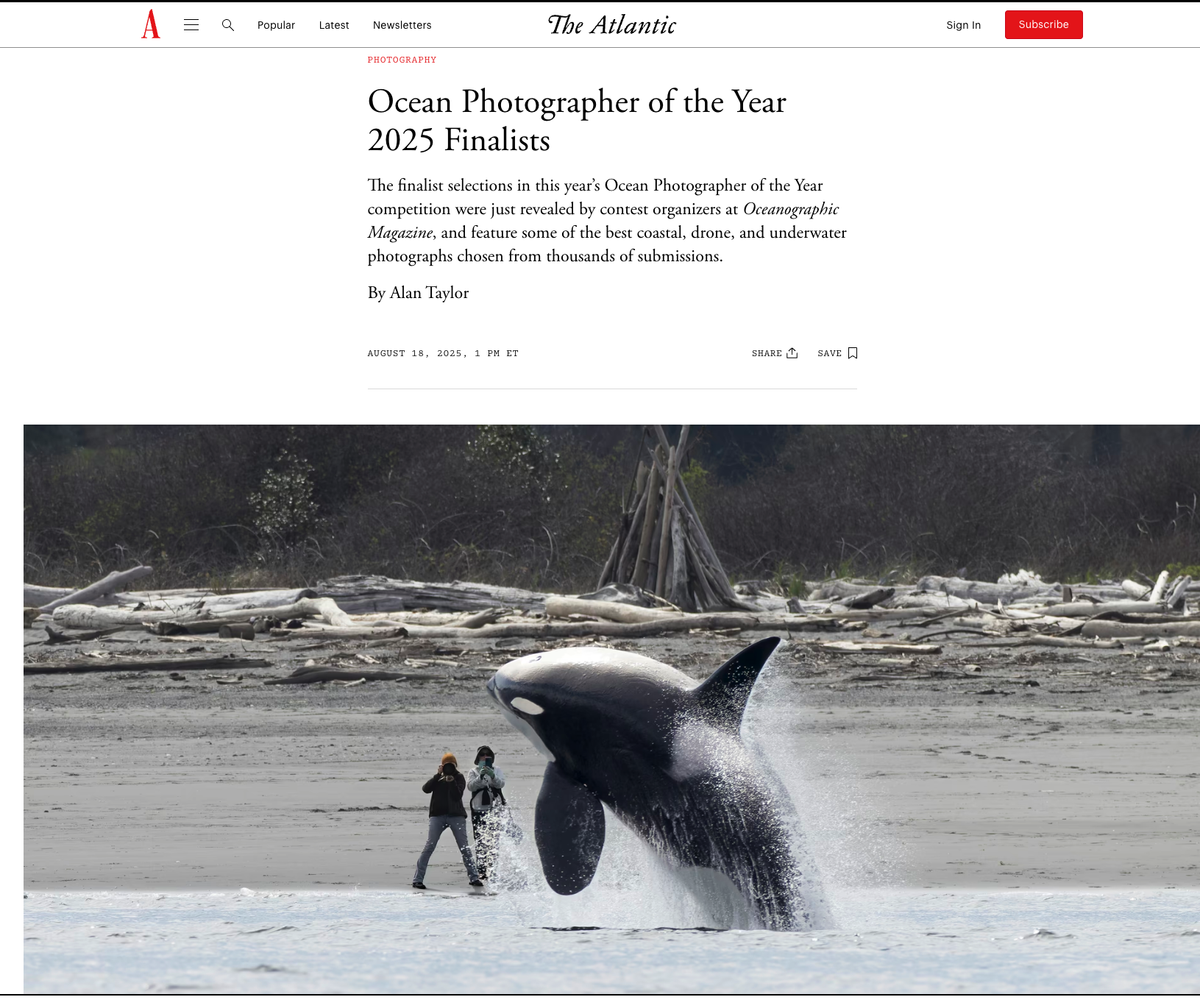

https://www.theatlantic.com/photography/archive/2025/08/ocean-photographer-year-2025-finalists/

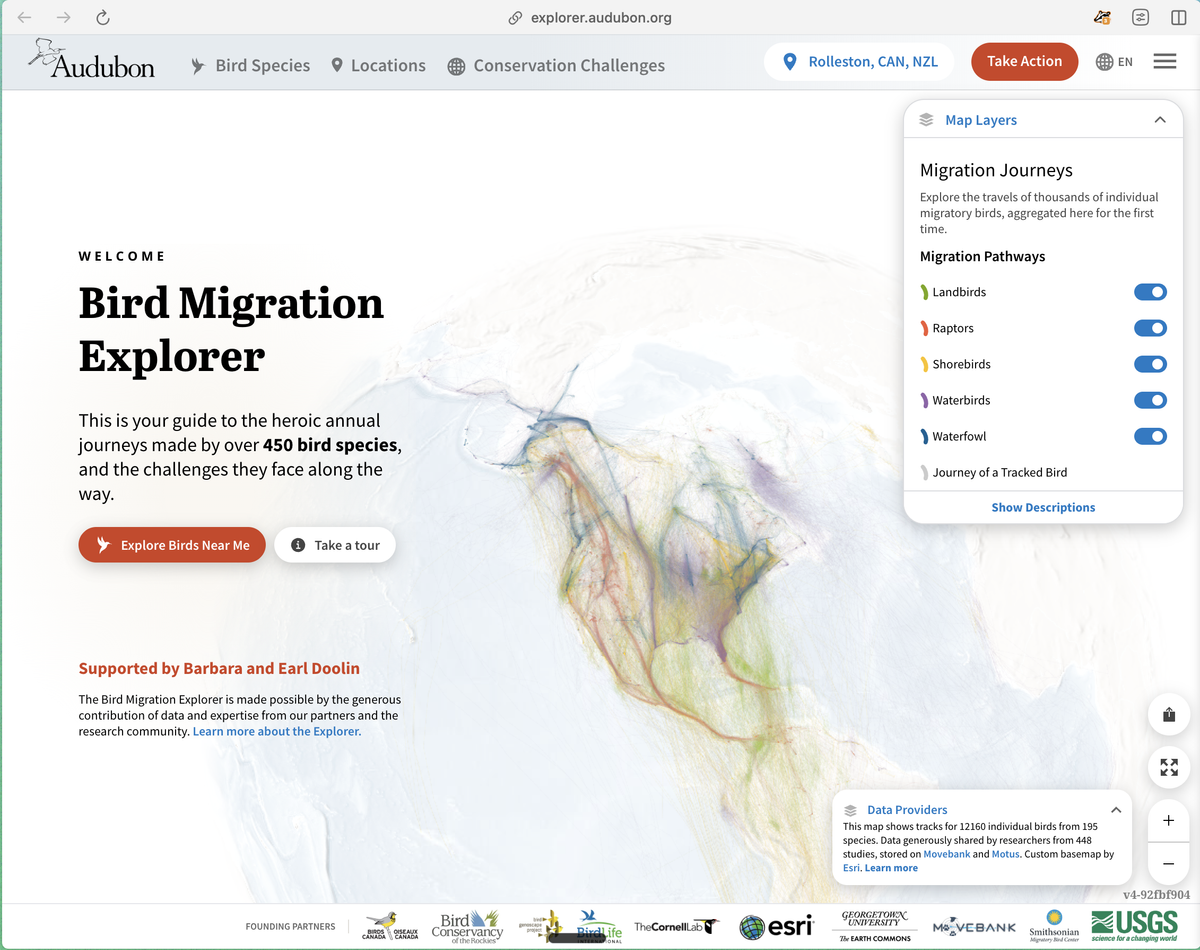

https://explorer.audubon.org/home

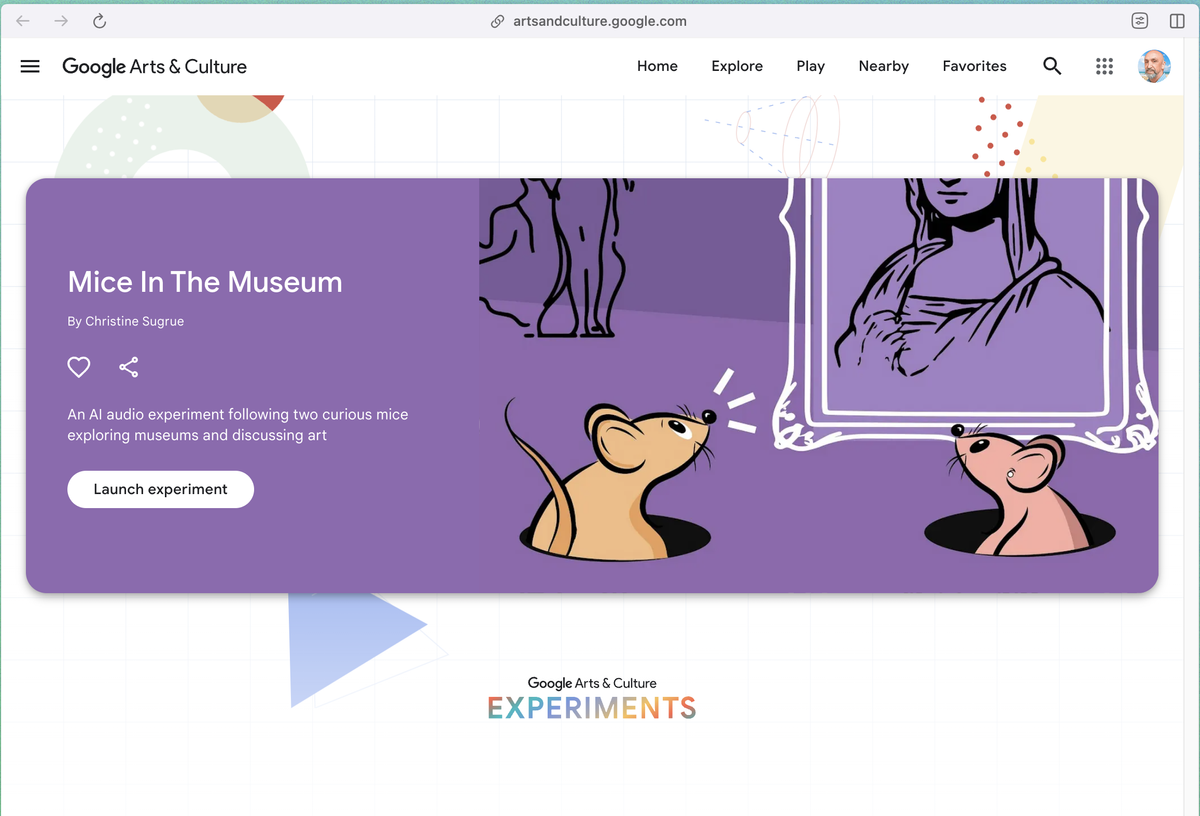

https://artsandculture.google.com/experiment/mice-in-the-museum/

Techie Tips:

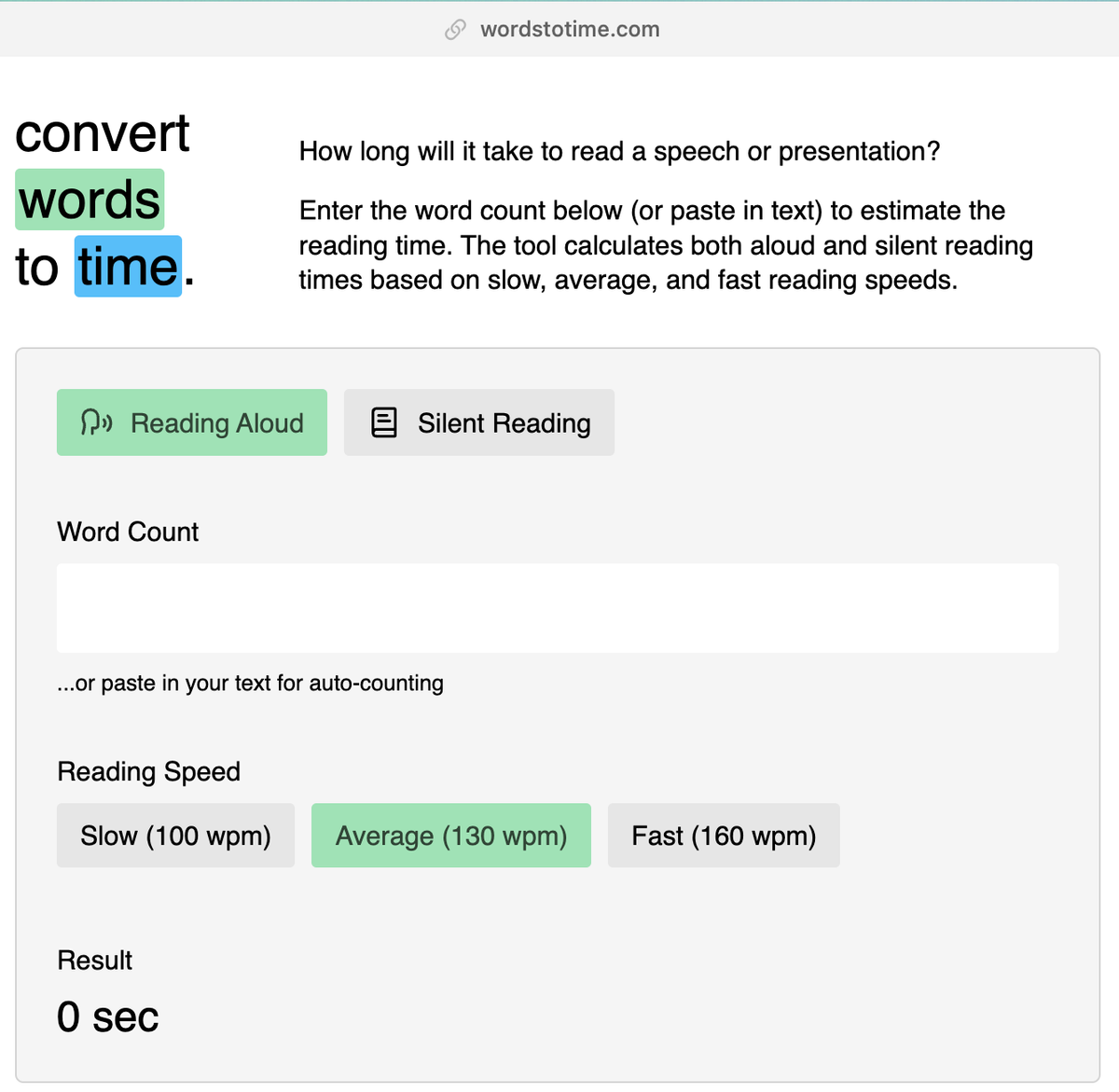

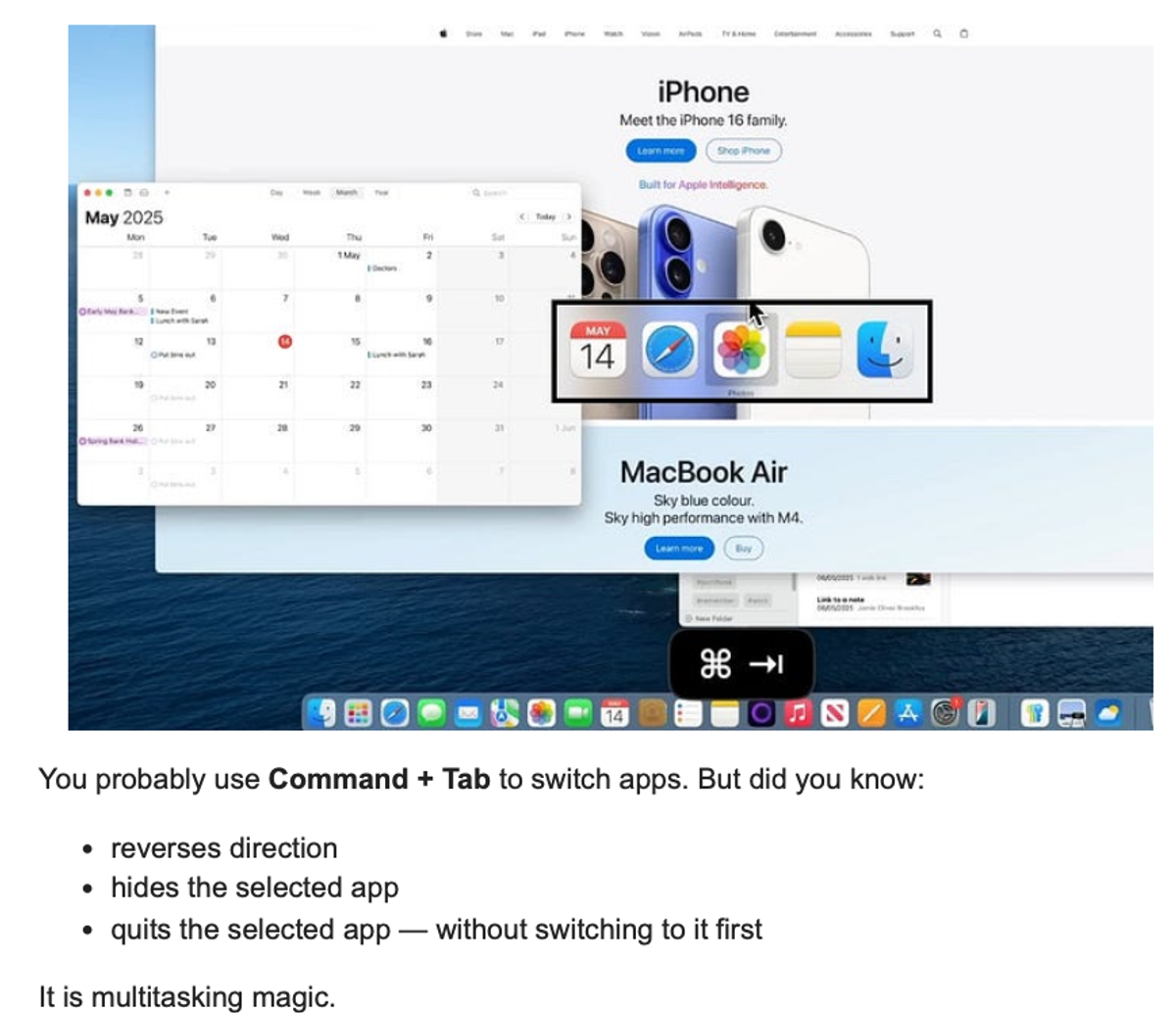

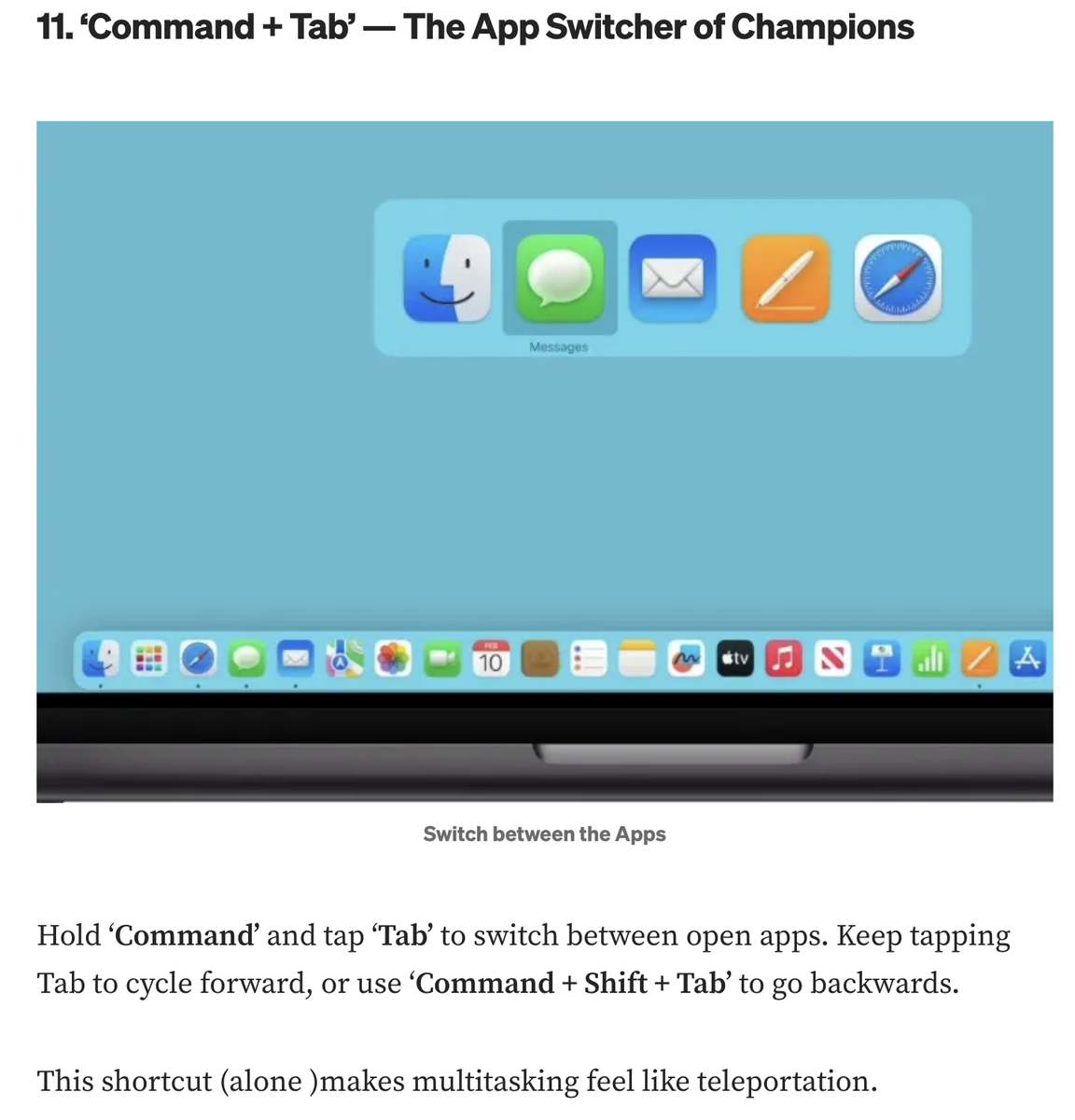

Master the App Switcher

Full-Screen File Previews

You probably know Spacebar gives you a Quick Look of files.

But if you press Option + Space, you get a full-screen preview (ideal for images, PDFs, or

videos).

Expert Photo Tip

I usually put little effort into taking photos, but this tip makes me want to snap more.

Turn your phone upside down so that the lens is facing downward.

Set the camera to 2x zoom.

Step back from your subject.

This setup helps create more natural human proportions and reduces facial distortion.

Sketches:

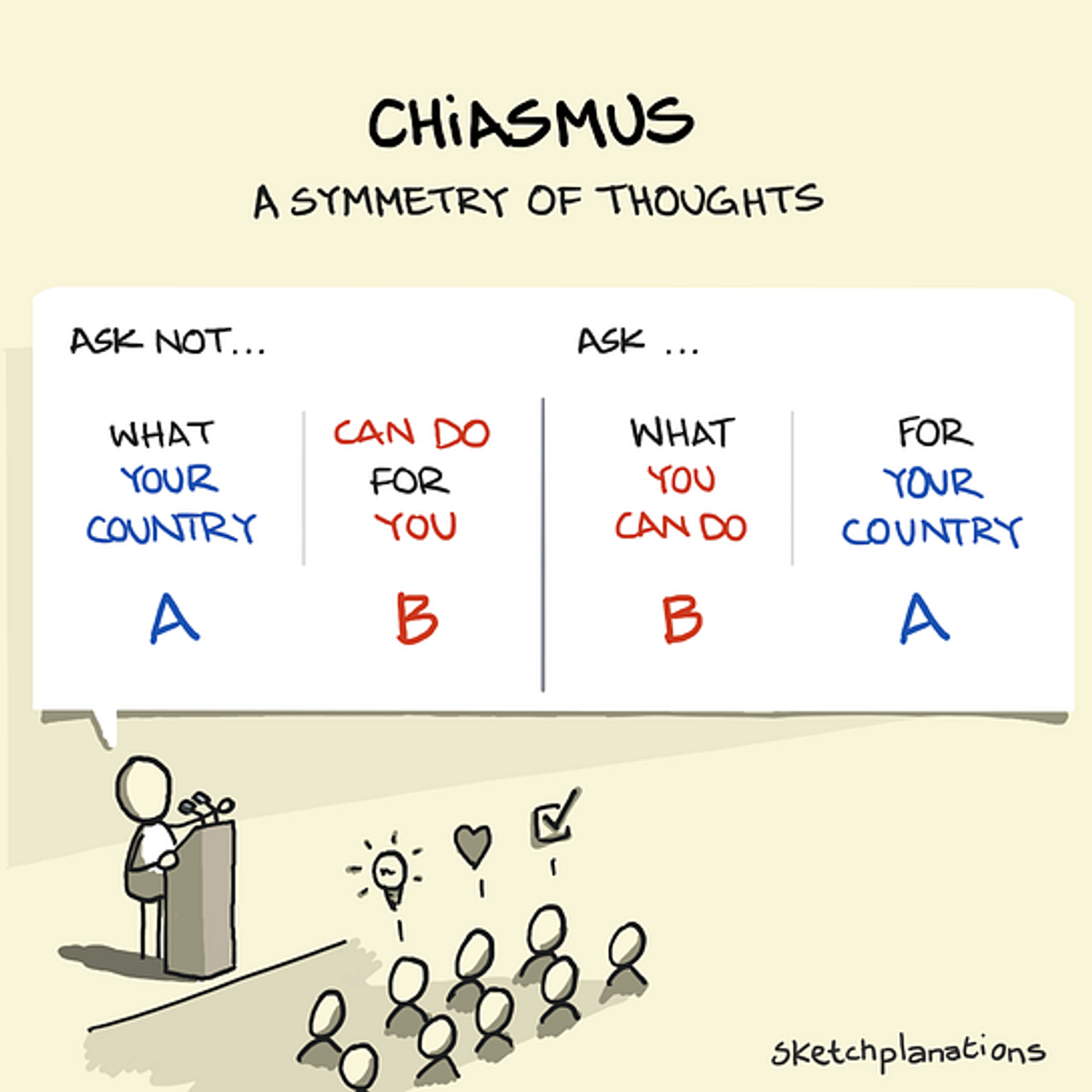

When JFK, in his inaugural address, said:

"Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country," he wasn’t just delivering one of the most famous presidential lines ever; he was also using a rhetorical device called chiasmus.

What is Chiasmus?

Chiasmus is the name for arranging words, phrases, or ideas in the structure A-B-B-A. The second half of the sentence mirrors the first half, flipping the order. The symmetry of thought of this rhetorical technique makes language more memorable, striking, and often more persuasive.

Chiasmus can involve just ideas, or the exact repetition of words (that special case is called antimetabole).

More examples:

Chiasmus reappears frequently in political speeches, literature, music, and everyday expressions. Mark Forsyth, who is full of brilliant and entertaining examples, notes that few presidents and presidential candidates in recent memory have resisted the lure of chiasmus.

Here are some well-known presidential examples:

"You stood up for America; now America must stand up for you." — Barack Obama

"Whether we bring our enemies to justice, or bring justice to our enemies, justice will be done." — George W Bush (Jr)

"Let us never negotiate out of fear. But let us never fear to negotiate." — JFK

"People the world over have always been more impressed by the power of our example than by the example of our power." — Bill Clinton.

"The difference between them and us is that we want to check government spending, and they want to spend government checks." — Ronald Reaga.n

"America did not invent human rights; human rights invented America." — Jimmy Carter.

"In the end, the true test is not the speeches a president delivers, it's whether the president delivers on the speeches." — Hillary Clinton.

Aside from presidential candidates, other examples include:

All for one and one for all — the 3 Musketeers

Tea for two and two for tea, Me for you and you for me — the 1925 Musical, No, No Nanette

When the going gets tough, the tough gets going — Billy Ocean

With my mind on my money and my money on my mind — Snoop Dogg

I have never forgotten a print-out at the bottom of some stairs in UC Berkeley: "Take the stairs and add years to your life and life to your years."

What makes Chiasmus Effective?

I'm not sure if there is a scientific reason why chiasmus is appealing to us, but a few ideas come to mind.

It's rhythmic. The mirrored structure is naturally pleasing to the ear, as in Edward Lear's, "They went to sea in a Sieve, they did, In a Sieve they went to sea."

It's clever. Chiasmus surprises us by flipping words or ideas into a new sense, as in the use of the word "life" in Mae West's "It's not the men in my life, it's the life in my men."

It's easy to remember. If you can remember the first half, you can often reconstruct the second: A place for everything...and everything in its place.

Chiasmus vs Antimetabole

Chiasmus is about flipping ideas, as in:

The green of summer; an autumn of blue — Chiasmus (ideas inverted - colour, season, season, colour)

When the same words are repeated in reverse order, it's technically antimetabole, a special case of chiasmus, as in most of the examples here:

Mankind must put an end to war, or war will put an end to mankind (JFK)— Chiasmus and antimetabole (mankind, end to war, war will end, mankind)

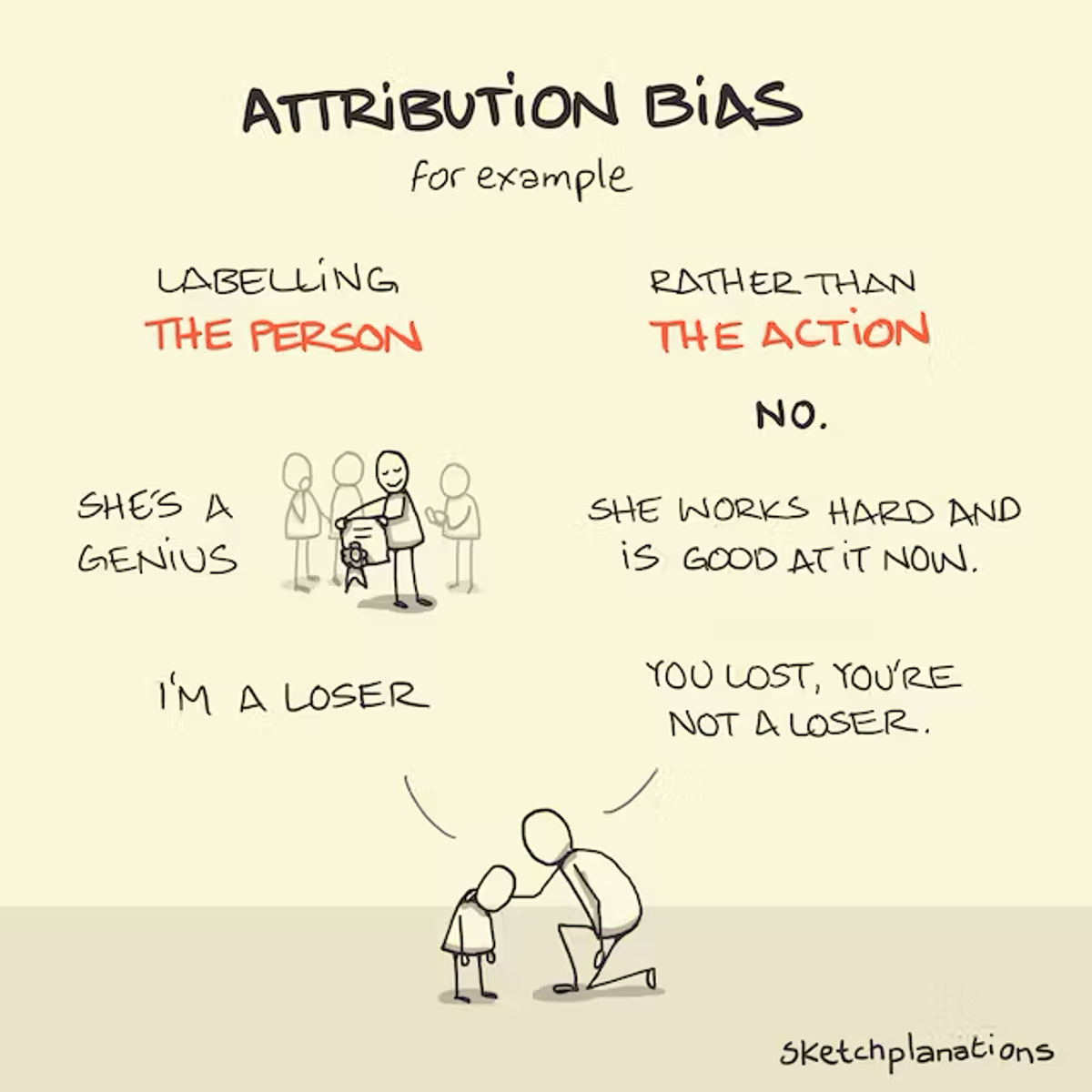

Attribution Bias

Attribution bias includes a set of more specific biases where we may attribute behaviour to fixed personality traits or characteristics of a person rather than specific circumstances or actions.

For example, a child may be labelled a genius or gifted when they actually had a supportive environment and worked hard, or someone may be labelled a loser rather than recognising specific circumstances that led to some failures.

Criticism — one of the four horsemen of relationship apocalypse — can become toxic when it's attributed to someone's personality traits. For example, calling someone 'lazy' rather than sharing how it makes you feel when they don't keep the place tidy.

Article:

How to Think Like Leonardo da Vinci

https://artofmanliness.com/character/advice/think-like-da-vinci

Brett & Kate McKay

How to Think Like Leonardo da Vinci: Seven Steps to Genius Every Day by Michael J. Gelb.

The book draws inspiration from the life of Leonardo da Vinci to explore habits that can enhance your thinking, unlock creativity, and foster a flourishing life.

How to Think Like Leonardo da Vinci is an enjoyable read that mixes history and self-

improvement and combines philosophical ideas with concrete practices that can be

incorporated into your life.

Below - the “Seven Da Vincian Principles” Gelb lays out in the book, along with

some corresponding exercises.

The 7 Da Vincian Principles and Practices to Cultivate Them

1. Curiosità – Cultivating Curiosity

Leonardo never stopped asking questions throughout his life.

Unfortunately, as we age, we tend to become less curious. We often accept what we

know as sufficient and stop exploring the unknown.

To cultivate the principle of Curiosità, Gelb recommends that you:

Keep a notebook. Leonardo always kept a notebook with him. He filled

thousands of pages with observations, sketches, and questions. Do likewise. Write about

anything that catches your attention in your notebook. Doodle in it. Capture ideas. Write

down questions. How to Think Like Leonardo da Vinci inspired me to keep a pocket

notebook with me at all times throughout high school and into my adult life.

Make a list of 100 questions. Write out 100 questions. They can be about anything and

everything — whatever you wonder about. Make the list in one sitting. Write quickly, and

don’t overthink. This exercise reveals themes or topics that are important to you.

I did this exercise in my teenage journal; here are a few of the questions I wrote down:

What will I be like in 10 years?

Where will I live when I’m older?

What is the measure of a man?

Am I reaching that measure?

Is technology the downfall of society?

2. Dimostrazione – Testing Knowledge Through Experience

Leonardo sometimes referred to himself as a discepolo della esperienza — a “disciple of

experience.” He didn’t just take other people’s word for things; he experimented, tested,

and observed for himself.

To develop Dimostrazione, Gelb recommends that you:

Inventory the origin of your beliefs. Make a list of three beliefs and mental models that

guide your navigation of life. After you’ve made your list, examine each belief and

consider the degree to which the following sources have influenced them: media, other

people, and your own experience.

If you realise that the first two sources, rather than direct experience, have primarily

shaped your beliefs, Gelb recommends looking for ways you can validate those beliefs

through direct experience.

3. Sensazione – Sharpening Your Senses

What made Leonardo such an amazing artist was his keen observation skills and ability

to fully immerse himself in the sensory details of the world around him.

Here are a few Leonardo-inspired sense-sharpening practices:

Describe a sunset. Find a quiet place outside at dusk to observe the sunset. Write down

a detailed description of the experience.

Learn to draw. For Leonardo, drawing was a foundational skill for understanding the

world. His notebooks are filled with sketches. You don’t have to be an expert artist like

Leonardo, but learning how to draw can be a powerful tool for acquiring knowledge. It can

help make abstract ideas concrete.

4. Sfumato – Embracing Uncertainty

One of Leonardo’s greatest strengths was his ability to be comfortable with ambiguity.

The Mona Lisa is a perfect example of this. The word sfumato (which means “smoky” in

Italian) describes Leonardo’s painting technique of blending edges, but for Gelb, it also

reflects his ability to navigate uncertainty and the tension that comes with it.

To develop the principle of Sfumato, Gelb recommends that you:

Cultivate “confusion endurance.” Contemplate paradoxes in life, such as:

Joy and Sorrow — Think of the saddest moments of your life. Which moments were

most joyful? What is the relationship between these states?

Strength and Weakness — List your strengths and weaknesses. How are these

qualities related?

5. Arte/Scienza – Balancing Art and Science

Leonardo seamlessly blended science and art. His anatomical drawings are both

scientifically accurate and aesthetically stunning. He saw no divide between logic and

creativity.

To cultivate arte/scienza, Gelb recommends you:

Practice mind mapping. Inspired by Leonardo’s habit of nonlinear note-taking, mind

maps use images and words to connect ideas organically. In your notebook, mind map

questions like:

What do I want to accomplish in the next 5 years

What do I know (or need to know) about [topic]?

What steps do I need to take to reach this goal?

What should I include in my trip/event plan?

What areas of my life need more attention right now?

What are the root causes of this issue?

What are possible solutions to this problem?

What are the pros and cons of my two options for this decision?

What criteria should I use to make this decision?

What are the short- and long-term consequences of each choice?

6. Corporalità – Physical Fitness and Poise

Leonardo didn’t just exercise his mind — he took care of his body, too. He was known for

his strength, endurance, and grace. According to sources, Leonardo was able to bend a

horseshoe with his bare hands. He combined brains and brawn!

To cultivate Corporalità yourself, you can practice the many habits that promote physical

health and poise, like taking a morning walk, strength training, eating a balanced diet, and

improving your posture.

Gelb also recommends two quirkier practices:

Juggle. According to biographer Antonina Valentin, Leonardo was a juggler. Gelb thinks

juggling can help your mental and physical acuity.

Cultivate ambidexterity. Gelb notes that Leonardo was naturally left-handed but also

developed his ability to work with his right hand. He recommends we follow the master’s

example and become ambidextrous ourselves. Spend the day doing your usual tasks like

writing and brushing your teeth with your non-dominant hand. Gelb also recommends

writing and drawing with your left and right hand at the same time.

7. Connessione – Seeing Interconnectedness

One of the keys to Leonardo’s creative genius was his ability to combine and connect

disparate ideas to form new concepts. A famous connection that Leonardo made was

between water and hair. He noted that they moved in similar ways, and seeing that

connection allowed him to draw both of those things better.

To cultivate Connessione, Gelb recommends that you:

Find connections. Get your notebook and write down three connections between the

following:

An oak leaf and a human hand

A laugh and a knot

Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” and rain

If you want to cultivate a more curious, creative, and well-rounded mind and become a

real Renaissance man, try some of the exercises above and get writing, thinking, asking,

drawing, and juggling yourself.

Book Recommendation:

Why We Remember

A radical reexamination of memory by the pioneering neuroscientist and internationally-renowned memory researcher.

We talk about memory as a record of the past, but here’s a surprising twist: we aren’t supposed to remember everything. In fact, we’re designed to forget. Over the course of twenty-five years, Charan Ranganath has studied the flawed, incomplete, and purposefully inaccurate nature of memory, finding that our brains haven’t evolved to keep a comprehensive record of events, but to extract the information needed to guide our futures.

Using fascinating case studies and testimonies, Why We Remember unveils the principles behind what and why we forget, and sheds new light on the silent, pervasive influence of memory on how we learn, heal, and make decisions. Examining the roles that attention, intention, imagination, and emotion play in the storage of memories provides a vital guide to remembering what we hold most dear.