Managing Staff Complaints- Part 2 from MPB News (Term 3, 2025)

Managing staff complaints can be complex and demanding, and we strongly encourage members to seek advice and support from the Department’s Conduct and Integrity Division by calling 03 7034 6768 or emailing employee.conduct@education.vic.gov.au.

In this edition, we are pleased to share Part 2 of the Merit Protection News series, which focuses on effective approaches to managing staff complaints. The articles provide practical guidance, examine common grievance themes, and outline key considerations to assist members in mitigating risks and preventing unnecessary escalation.

Best tools for solid case on complaints

Precise framing of allegations and a sound evidence base are key to good complaints handling across the teaching service, advises the Merit Protection Boards.

Not only do these two factors provide solid ground for leaders, they send a strong signal should a matter invariably find its way before the MPB.

As current caseload data for 2025 shows a clear spike in complaint-related grievances, the MPB has cast a spotlight on themes vital to good practice in complaint cases.

Central among these are careful crafting of allegations and focusing on a good evidence base, paying attention to weight and reliability, according to MPB Senior Chairperson Steve Metcalfe.

The stubbornness of latest complaint numbers, on the back of a rise over the second half of 2024, reflected repeated issues with these key themes Mr Metcalfe revealed.

Other areas that stood out as ongoing hotspots were the role of hearsay evidence and, for appellants, ensuring any decision or action taken directly affected their employment, such that it was “an appealable action” under Ministerial Order 1388, Mr Metcalfe said.

“If allegations fail to specify the nature of a complaint including key particulars or, equally, if evidence is not fully captured and capable of review, then decision-makers risk framing rulings on an incomplete picture,” he outlined. “Our job at the MPB is not to re-make the decision after the principal, but, in the context of our powers, consider if the decision made breached any Order, policy or is unreasonable.

In other words, was the decision reached a sensible and justifiable option available,” he said.

Mr Metcalfe highlighted that, when complaints grievances reached the MPB, it carefully considered if processes followed were consistent with the Department of Education’s recently updated Guidelines for Managing Conduct and Unsatisfactory Performance in the Teaching Service.

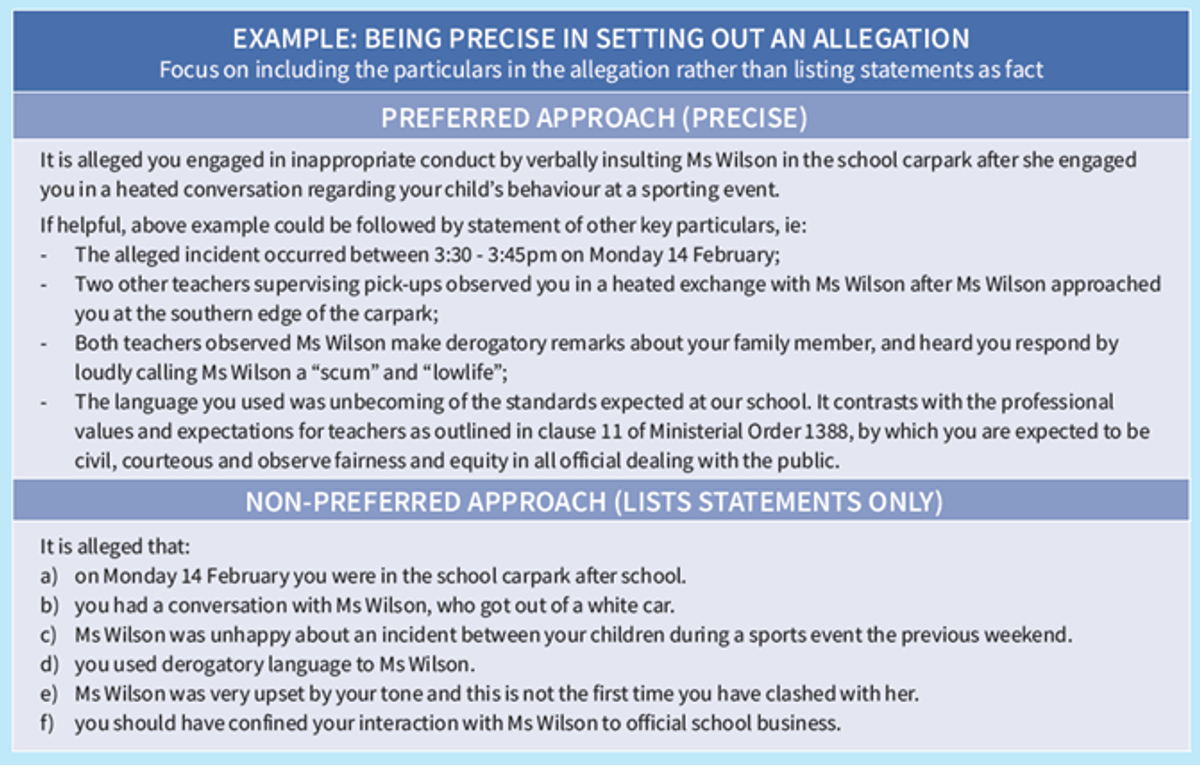

“We first look at allegations, which should ‘establish the precise nature of the complaint’ and they should point an investigation directly to the alleged behaviour or conduct of the employee that would be considered inappropriate or unprofessional,” he said.

“Both of these aspects are vital to helping ensure procedural fairness – an individual who is the subject of the matter needs to be able to see and understand the details so they can respond properly.” (See Example of precise detailing of an allegation below)

Next came the key theme of evidence, Mr Metcalfe explained, whereby the principal or decision maker had to consider whether the weight and reliability of evidence demonstrated the complaint had been substantiated or not.

He confirmed the standard of proof to be applied by schools in complaints cases was the civil standard ‘on the balance of probabilities’ – that is, it was more likely than not the alleged conduct occurred.

This is an expectation of both the Department’s Guidelines and the MPB. It differs from the ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ standard, which is the criminal burden of proof.

“Such a standard requires the decision-maker to feel an actual persuasion as to the existence of the alleged facts. There must be a reasonable satisfaction a piece of evidence is more likely than not to be true,” he said.

Mr Metcalfe stressed it was vital to obtain and also document eye-witness testimony of any third-party witnesses to a matter, where it existed.

This could include student accounts, but he conceded such an area became more challenging with much younger primary students.

“If there are direct witnesses to a particular incident, the MPB strongly recommends they be interviewed or provide a statement as soon as possible, and records should be made as they can also help with any later review,” Mr Metcalfe said.

“Independent witnesses can assist in clarifying the nature of the alleged matter. For example, if it’s alleged physical contact, such as a claim a teacher hit or pushed a student during class, then several others nearby might be witnesses to the event,” he said.

“With all such evidence, the MPB looks to see if it helps build a picture with consistent themes or not, and may go towards supporting the reasonableness of a decision.”

On the topic of hearsay evidence, Mr Metcalfe advised “the Board would prefer to see direct testimony if it exists”. He indicated the MPB could take into account any hearsay evidence during hearings, but the crucial difference here was the weighting applied.

“The Board is of the view there is significant risk that factors become distorted in relay of hearsay evidence, not necessarily through any malicious intent but through the individual nature of human communication. This is influenced by a raft of factors including the knowledge, disposition, language use, listening skills and individual interpretation,” he said.

“We also look at the absence of evidence where it should have, likely, existed. This could be a group setting or a regular class where it would be reasonable to assume someone else might have noticed or observed something,” he added.

In cases where there were no independent witnesses to provide evidence, Mr Metcalfe pointed out that the Department’s Guidelines advised a principal or decision maker could make a decision based on the credibility of the parties involved.

For appellants lodging grievance bids, Mr Metcalfe stressed that the Ministerial Order

specified a decision or action could only be appealed where it “directly affects the employee in their employment”.

Mr Metcalfe encouraged individuals to resist making submissions solely on the basis of claiming the process was flawed or unreasonable. Instead, they should consider if any outcome reached included or directed an action that directly affected them in their work.

“Examples of this could be decisions that include a direction to undertake specific additional training, supervision or mentoring, and recording specific actions on your employment record,” he said.

“These are employment actions and, as such, are appealable actions in the context of the relevant clause in the Ministerial Order.”

For full details on the Department’s Guidelines for complaints against employees, visit: https://www2.education.vic.gov.au/pal/complaints-misconduct-and-unsatisfactory-performance/policy-and-guidelines