Teaching & Learning Page:

Web Pages:

https://new.express.adobe.com/webpage/YObLHZ8m3jhyc?utm=&utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

https://stellarium-web.org/?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

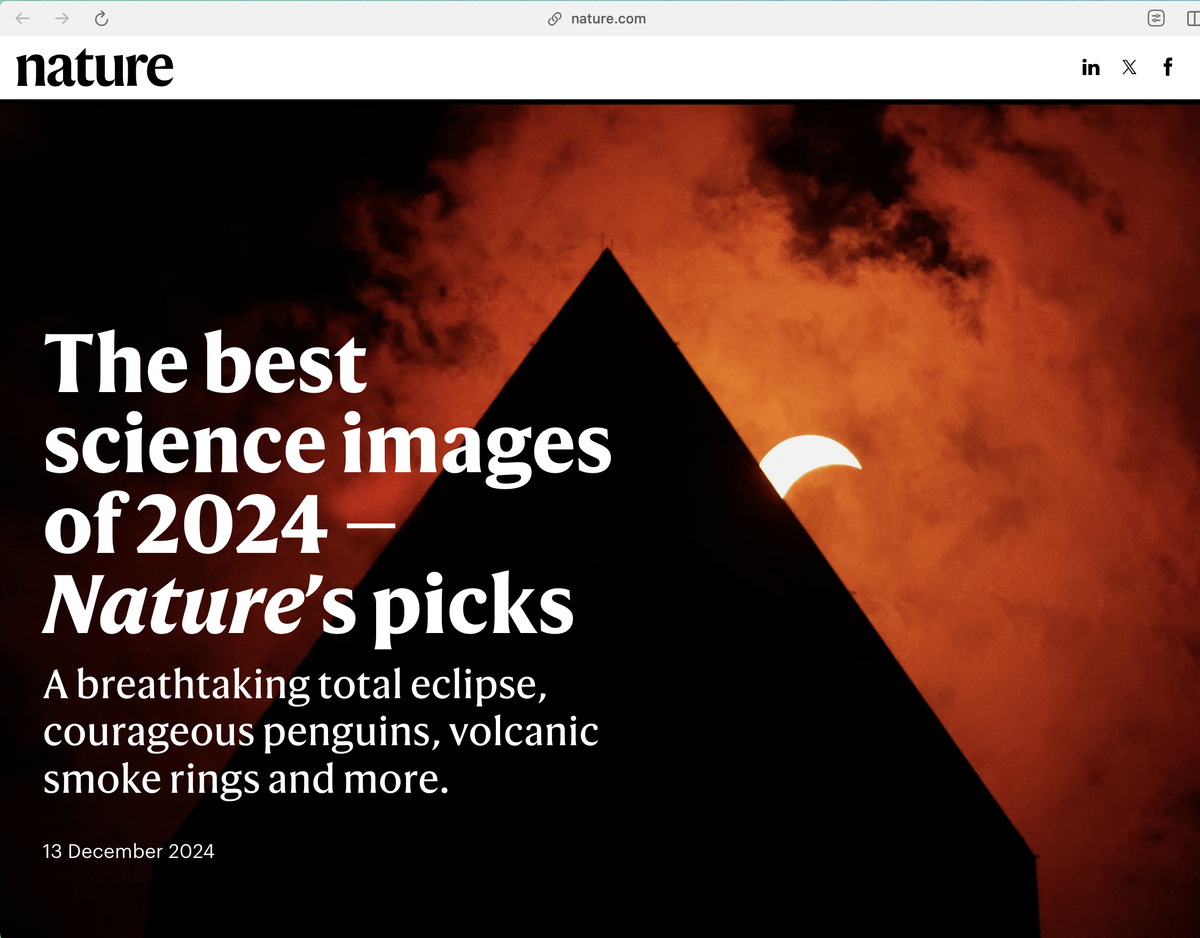

https://www.nature.com/immersive/d41586-024-03969-z/index.html?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

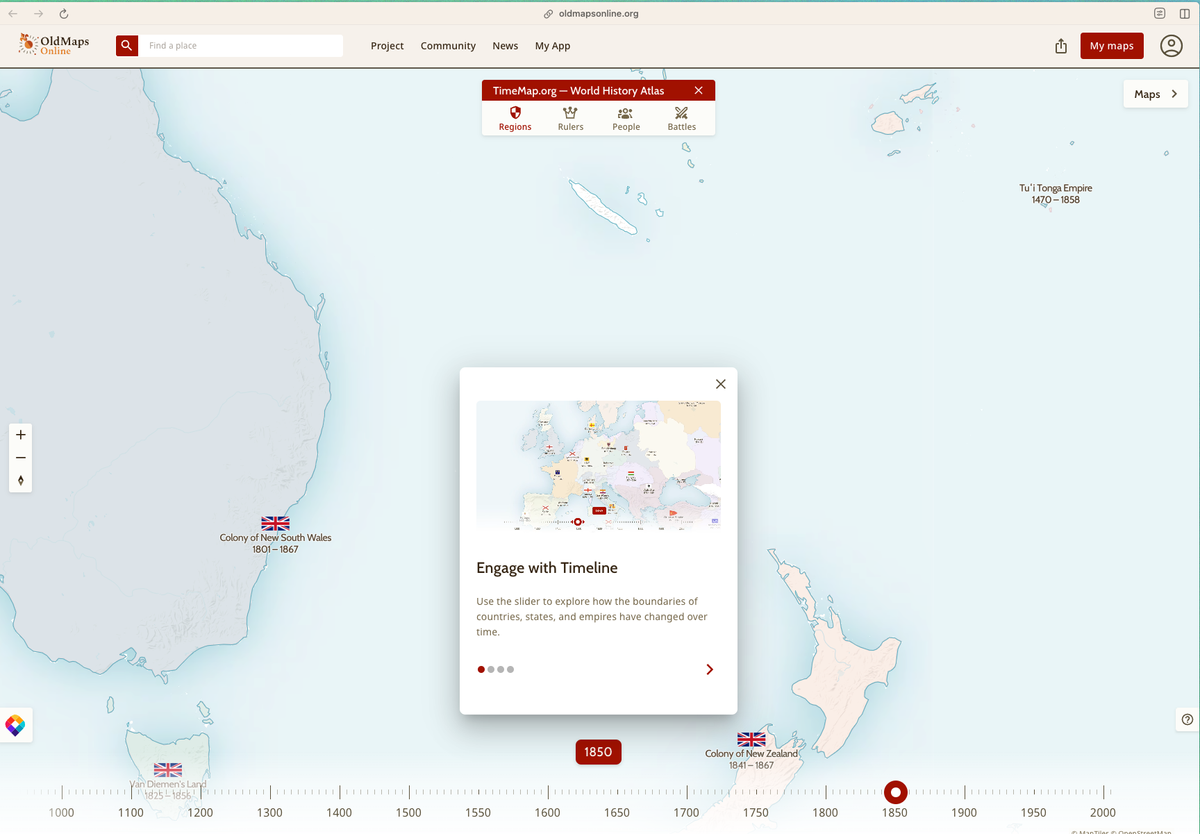

Maps Through History - Pick a Date See the Map of that Time

https://www.oldmapsonline.org/en/history/regions#position=4.5343/-31.97/172.86&year=1850

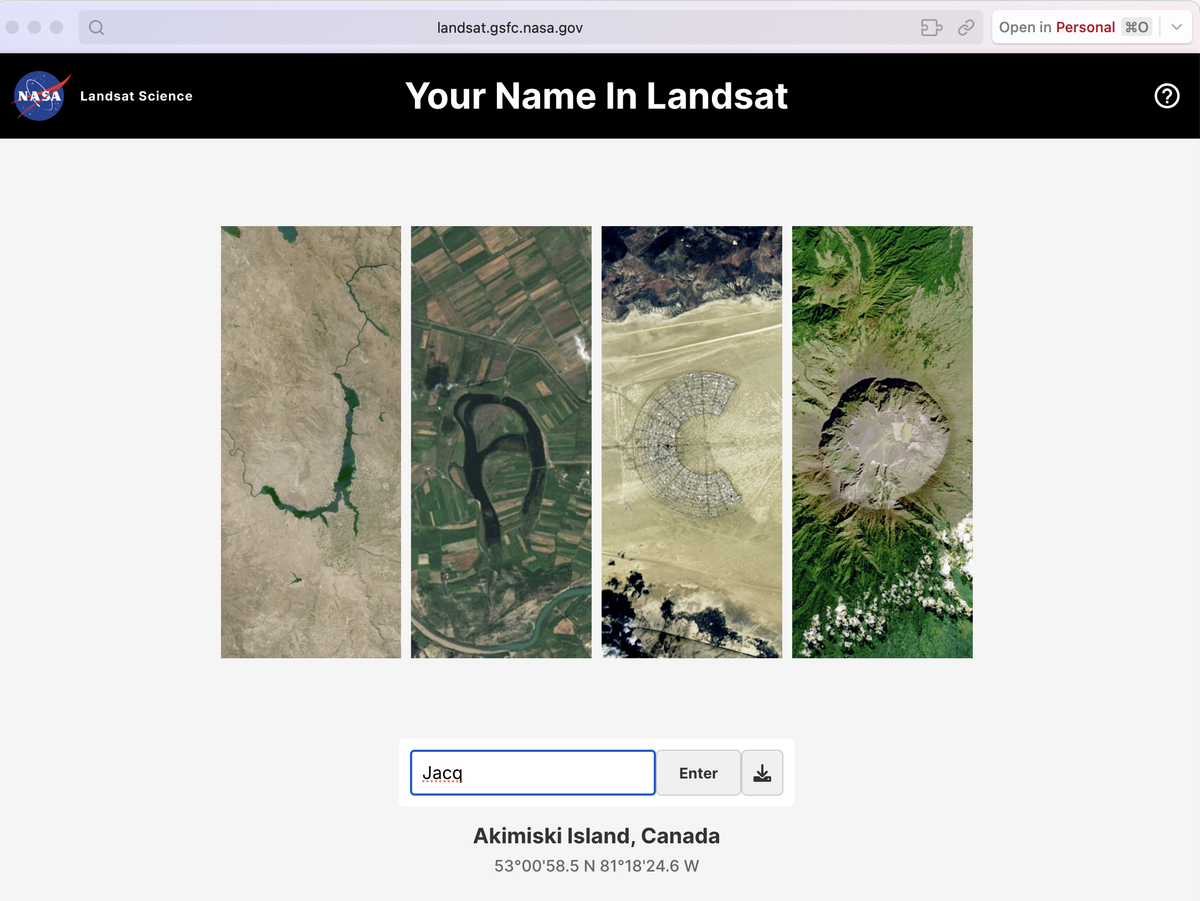

Your Name in Land Satellite Images - NASA

News That Focuses on the Positive

https://fixthenews.com/welcome/

Techie Tips:

Improve Your iPhone Functionality:

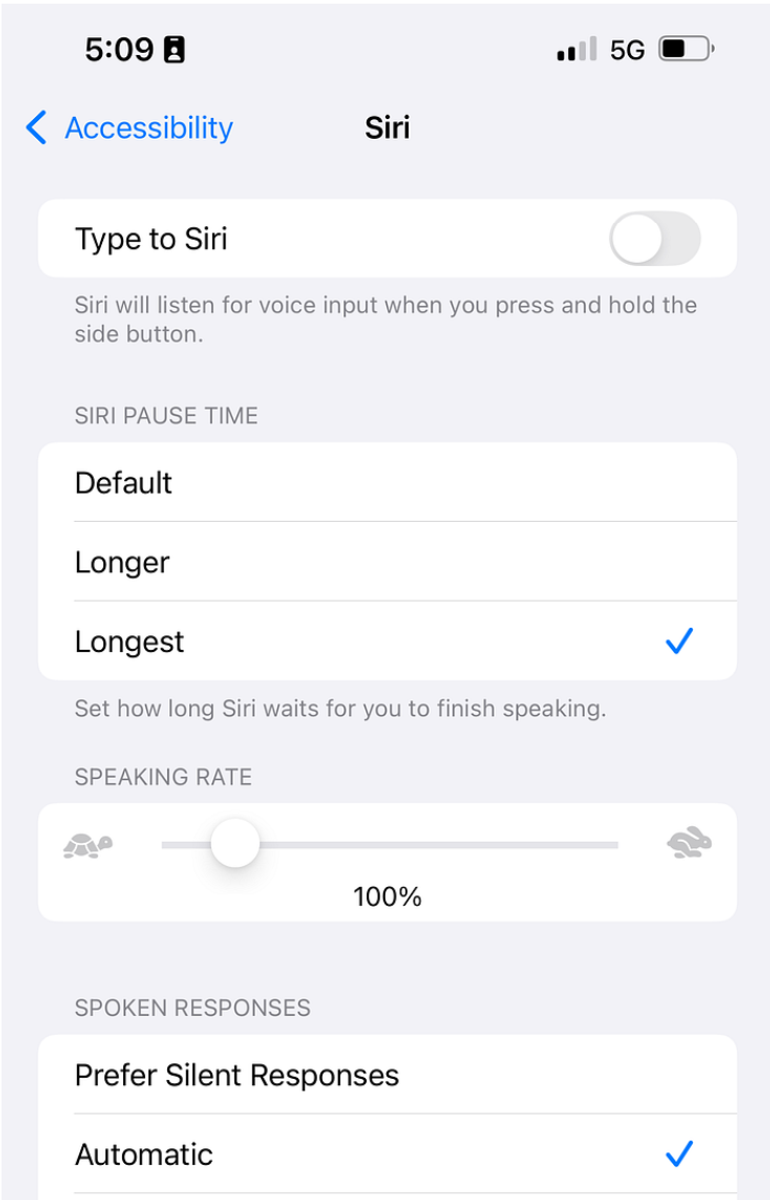

Make Siri More Patient

Does Siri rush you when you are trying to get your words out? iOS 18 lets you adjust how long Siri waits before cutting in. Follow the below steps to fix this.

Open Settings, scroll to Accessibility, and tap Siri.

Find Siri Pause Time and pick an option.

If you need a bit more time, go with Longest.

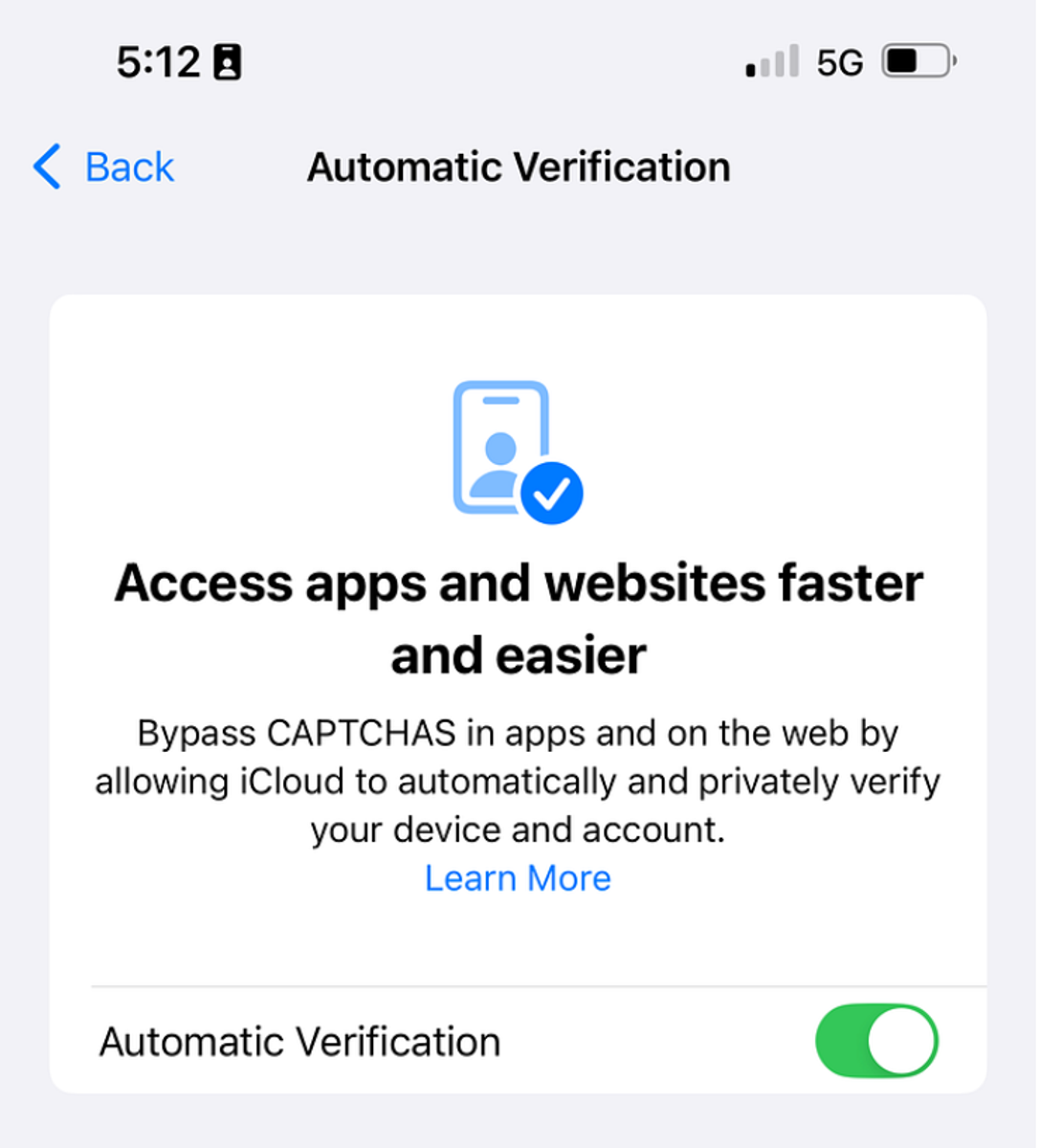

Turn on Automatic Verification for Captcha

Open Settings, and tap your name at the top.

Select Sign-In & Security and find Automatic Verification.

Tap it, then make sure the switch is on.

Sketchplanations - Spot the Common Theme...:

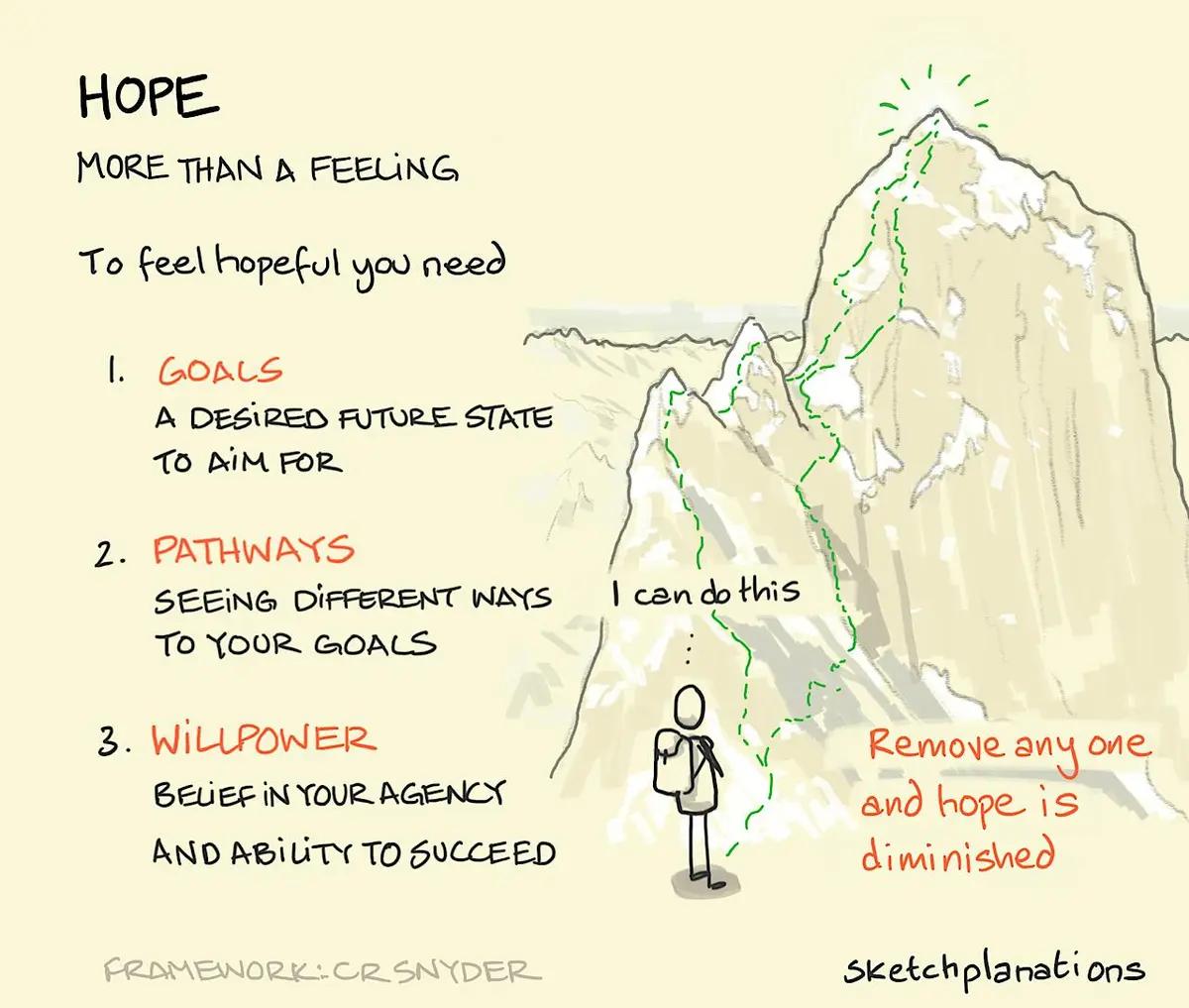

I hadn’t given much thought to hope, beyond it is a nice feeling to have, until I heard of CR Snyder’s cognitive model for hope, which shed new light on it for me.

He proposed a model of hope where (paraphrasing) an individual may be hopeful if they have:

Goals they desire.

If you don’t or can’t picture any future state you’d like, then you won’t have a lot of hope.

Pathways.

You need to see some ways that you may make step-by-step progress towards a goal.

Willpower or agency.

You need to be motivated and believe that you can succeed at your goal. With all of these, you can imagine feeling hopeful. Without any one of them, you probably won’t so much.

The mountain is the Ogre, a wholly impossible-looking peak scaled by Doug Scott and others for which I would have had zero hope to climb (no pathways, no willpower), and yet they remarkably did.

HT once again to Brené Brown in Dare to Lead

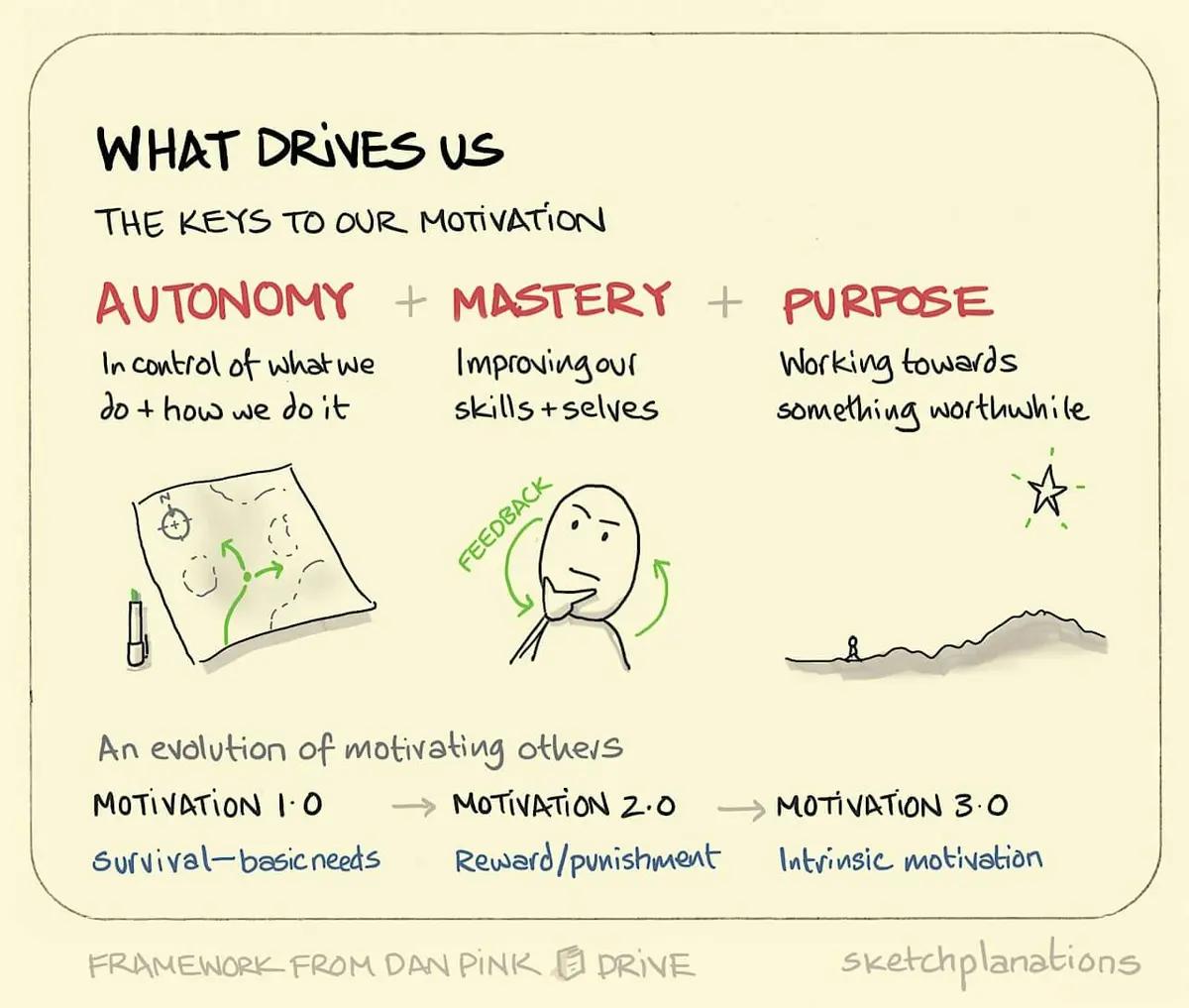

In Dan Pink’s book Drive, he looks at scientific studies showing that the all too common approach to motivating people involving rewards and punishments, or the carrot and stick approach, ultimately doesn’t help motivate people for the tasks and work we have to do today.

Instead, we do our best work when driven by intrinsic motivation — motivation from inside us rather than imposed externally, like rewards or punishments.

The three facets he highlights that help intrinsic motivation are:

Autonomy:

Being in control and able to guide both what we do and how we do it.

Mastery:

Our desire to continually be improving and learning and bettering ourselves.

Purpose:

Working towards something we think is worthwhile. Having a North Star to aim for and a reason why it’s worth doing what we’re doing.

I find it a useful framework to think through whenever I’m not feeling motivated or when I want to help make sure the people I’m working with are motivated.

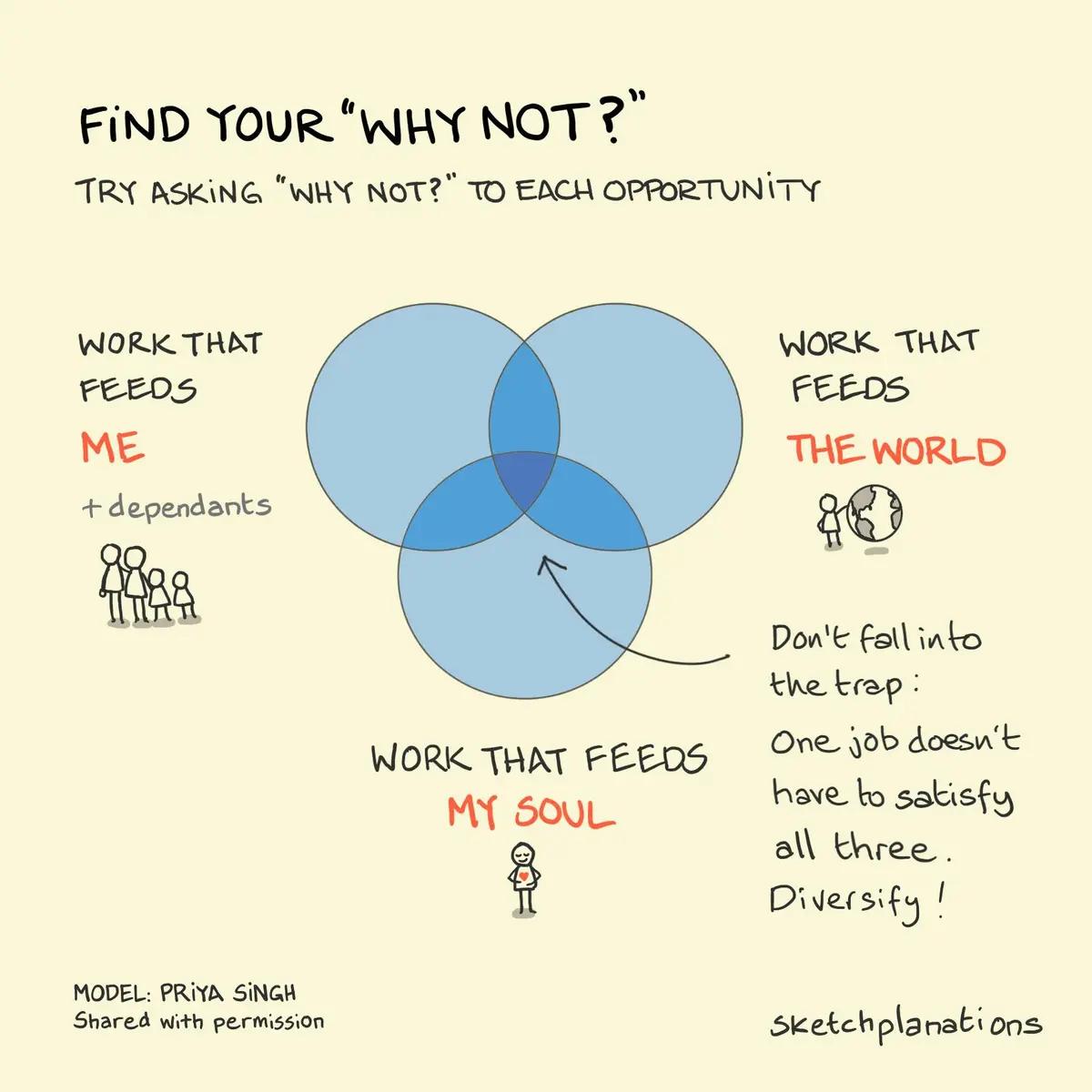

Many of us feel the desire to discover a singular purpose—the one true mission that defines what we should do and where we fit—our ikigai. But perhaps it doesn't have to be that way.

Priya Singh offers a refreshing alternative:

Instead of chasing one elusive “why,” recognise that we don't have just one singular purpose and that it can evolve. It’s not a pot of gold or treasure to be found, and we're not failing if we haven't found it.

Singh introduces a helpful framework with three types of work:

Work that feeds you and those that depend on you

Work that feeds the world

Work that feeds your soul

Your work may fit into one or more of these categories, but don’t fall into the trap of thinking it needs to fulfil all three at once.

Rather than striving for the mythical “dream job” that checks every box, embrace the possibility of balance across multiple roles or pursuits.

Rather than striving for the mythical “dream job” that checks every box, embrace the idea of balance across multiple roles or pursuits. Work that fits into just one or two of these areas is plenty—and can be deeply fulfilling.

Ask "Why Not?"

When faced with opportunities, try shifting your mindset. Instead of asking, “Why do it?” ask, “Why not?” Often, we reject ideas before even giving them a chance.

When presented with an opportunity or an idea, instead of asking why do it, try asking why not—practice not rejecting yourself before you’ve even started.

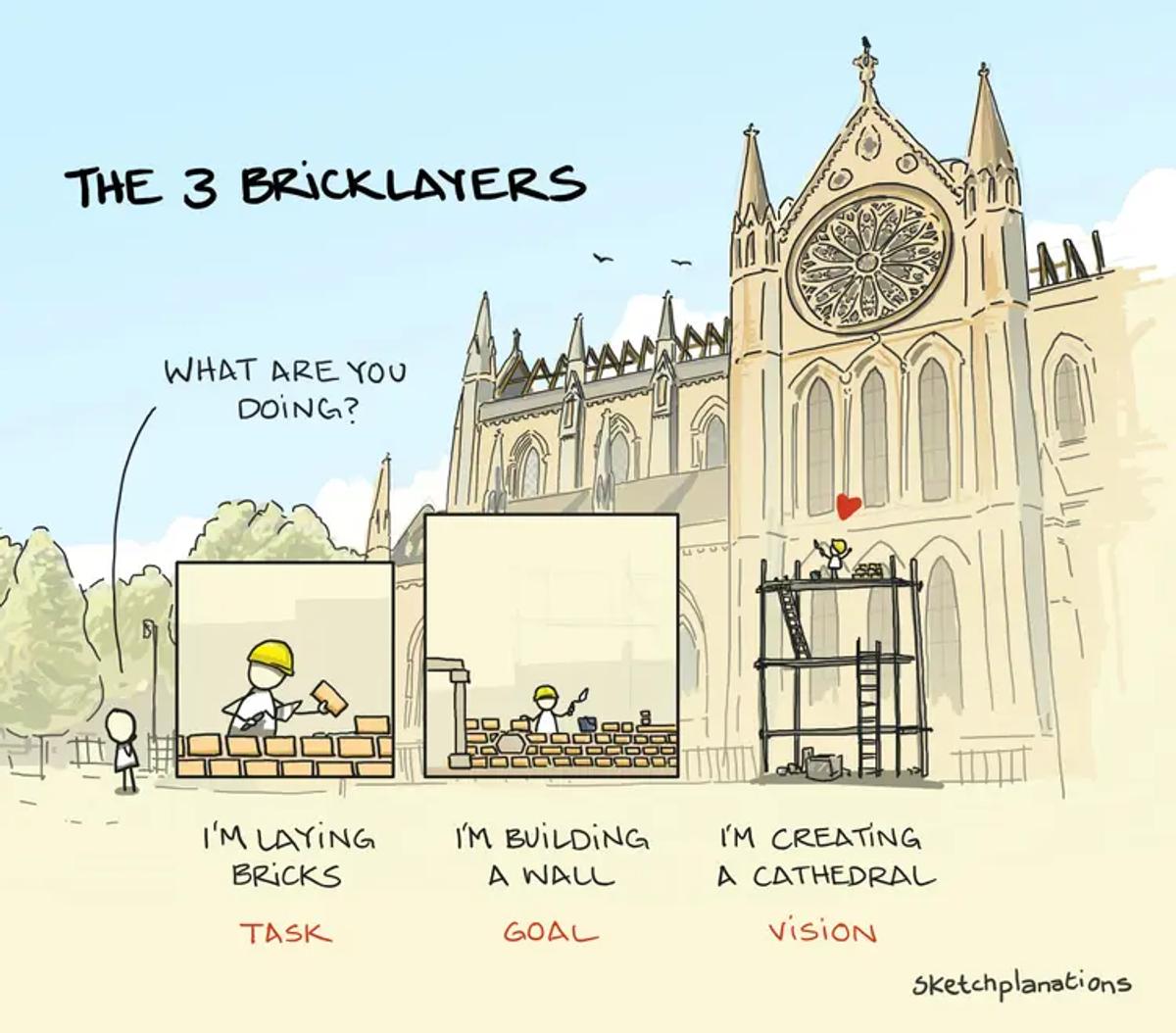

The Three Bricklayers’ story illustrates the power of purpose.

A simple version goes that a person walked past a building project and asked three workers the same question: “What are you doing?”

The first replied, “I’m laying bricks.”

The second replied, “I’m building a wall.”

And the third replied, “I’m creating a cathedral.”

The story highlights how we can view our work differently depending on whether we focus on the immediate task, the short-term goal, or the larger vision. The first worker focuses on the task at hand, the second sees the outcome of their work, and the third connects to the broader purpose of the project.

Finding Balance in Work

There’s value in all three perspectives. There can be a lot of pride and skill in laying bricks—or whatever your equivalent task is—as well as it can be done. Setting clear, intermediate goals keeps progress on track. And someone who spends all their time looking at plans or daydreaming about what the building will become may not lay bricks as well as they need to.

To do something well, we probably need a balance of all three aspects:

Pride and skill in detail and progress through clear intermediate goals, as well as vision and meaning for our work, understanding what I’m working towards and believing it’s worthwhile, are powerful motivators for me when the going gets tough.

This post isn’t really about cathedrals, but I studied the brilliant Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí in my teens. As a real-life cathedral metaphor, his incredible Basílica de la Sagrada Família in Barcelona is a striking example. Gaudí’s vision for the basilica has inspired generations of artisans and workers since he took over the project in 1882. Execution, however, has been a challenge, with construction ongoing today. But that hasn’t stopped it from inspiring and drawing in visitors for decades.

I like the three bricklayers parable as a reminder that when I’m grinding on something, it helps to reconnect with the why behind my effort.

Origins of the 3 Bricklayers Parable

Like many parables, this story has been told in different forms. An early version appears in Bruce Barton’s 1927 book What Can a Man Believe (p252), featuring Sir Christopher Wren, the architect of St Paul’s Cathedral in London after the Great Fire of 1666:

“One morning, he passed among the workmen, most of whom did not know him, and of three different men engaged in the same kind of work, he asked the same question: ‘What are you doing?’

From the first, he received the answer: ‘I am cutting this stone.’

From the second, the answer was: ‘I am earning three shillings and six pence a day.’

But the third man straightened up, squared his shoulders, and holding his mallet in one hand and chisel in the other, proudly replied: ‘I am helping Sir Christopher Wren to build this great cathedral.’”

Article:

We're only halfway through January, and everything is already on fire.

The 1.5°C target for global warming has been breached for the first time, Los Angeles has been burning for weeks, the President of the United States keeps talking about his territorial ambitions for Canada, Greenland and Panama, and the world's richest man has somehow managed to derail an entire week of British parliamentary debate.

Some of this apocalyptic tenor is imagined — far too many journalists have taken Trump's dead cat trifecta at face value — but much of it is all too real: The LA fires represent exactly the kind of complex, compound climate catastrophe that scientists have been warning about for decades. What's different now, though, even by the standards of our recent past, is that these events ricochet through our information ecosystem, amplified and distorted by a death pact between old and new media.

The common message from columnists is that we're living through an unprecedented disinformation age. Everyone is talking about how platforms degrade as they try to extract maximum value from users — and "slop," an increasingly common, endless stream of low-quality, algorithm-optimised online content. But in focusing on the pollution of our information streams, we're missing how the pipes themselves have been recalibrated to carry mostly sewage.

Watching it all go down, what strikes me isn't necessarily the degradation of the semi-mythical 'public sphere' but just how exquisitely sensitive English-speaking media has become to signals of disaster and discord. Our collective antenna for catastrophe has achieved a kind of terrible perfection. Each new crisis now arrives with crystalline reporting, high-resolution imagery, and an endless cascade of social media reactions. The Los Angeles fires have been horrific - and the entire world has been able to follow along in incredible detail with minute-by-minute updates, real-time maps and progress indicators.

News organisations have spent decades optimising for this kind of reporting. They've long known that it's the negative, highly arousing stories that get the most traffic - research shows that headlines have grown steadily more negative over the last two decades, with the proportion conveying anger and fear nearly tripling since 2013. And social media has supercharged this tendency. A comprehensive study of nearly 100,000 articles and over half a billion social media posts recently found that people are almost twice as likely to share negative news articles on social platforms.

Jaron Lanier had it right seven years ago when he said that social media was biased, "not to the Left or the Right, but downward." This didn't happen through some dramatic rupture but through a series of seemingly pragmatic choices: Legacy media, desperate for attention, has been producing increasingly negative content because that's what gets clicked on. Social media users, presented with this darker view of the world, share it more readily, which in turn encourages legacy media to produce even more of it. The result is a kind of perpetual motion machine of pessimism, each component feeding off the energy of the other's decline.

You know what's been noticeably absent from the headlines so far in 2025? Indonesia's revolutionary school meals program, global crop yields reaching record highs, two big pieces of bipartisan legislation for conservation in America, historic declines in crime in the United Kingdom, sea turtle populations increasing, emissions plummeting in Europe, pretty much anything related to the expanding global middle class, or record low unemployment figures around the world. Occasional glimpses of light, like the ceasefire in Gaza, barely register before being subsumed by the next crisis.

The irony is that we're living through one of history's great periods of progress, but we've lost the ability to see it because of the sludge of bad news. And that sludge is about to get a lot thicker. An 80-year-old felon and a 53-year-old ketamine addict now have the two biggest megaphones in the world, and the media will dutifully keep reporting their every utterance, no matter how inflammatory or incorrect because the clicks will keep coming. The biggest danger in the coming months and years will be the exhaustion of our critical faculties, our failure to withstand the noise, and the inevitable retreat into our personal spaces.

If we want to remain sane and engaged, we will need to do something about it. The solution isn't complicated, though it requires some effort: Get rid of algorithmic media and switch as much as possible to chronological media. Algorithmic feeds dominate social media and, through A/B headline testing and engagement metrics, most legacy media too. But there are alternatives. Books and newsletters get opened on your schedule, not the algorithm's. Platforms like Bluesky offer chronological feeds that aren't optimised for clickability.

The delivery mechanisms for the sludge may be largely undifferentiated, but our consumption doesn't have to be. The challenge isn't finding better algorithms or more aggressive regulation, though both might help. The challenge is learning to see our information ecosystem for what it has become — a vast apparatus fine-tuned to amplify our darkest impulses — and then having the wisdom to step away from it. It may seem quaint to suggest that emails and books could save us. But in an age where our collective attention has become everyone else's most valuable asset, the simple act of reclaiming when and how we consume information might be the most radical move we have left.

This one is too long to publish as an article, instead, it is available as a downloadable pdf:

How to Study in 2025.