The Green Page:

Bumble Bees Are Cultured

Here’s why this could change how we think about humanity.

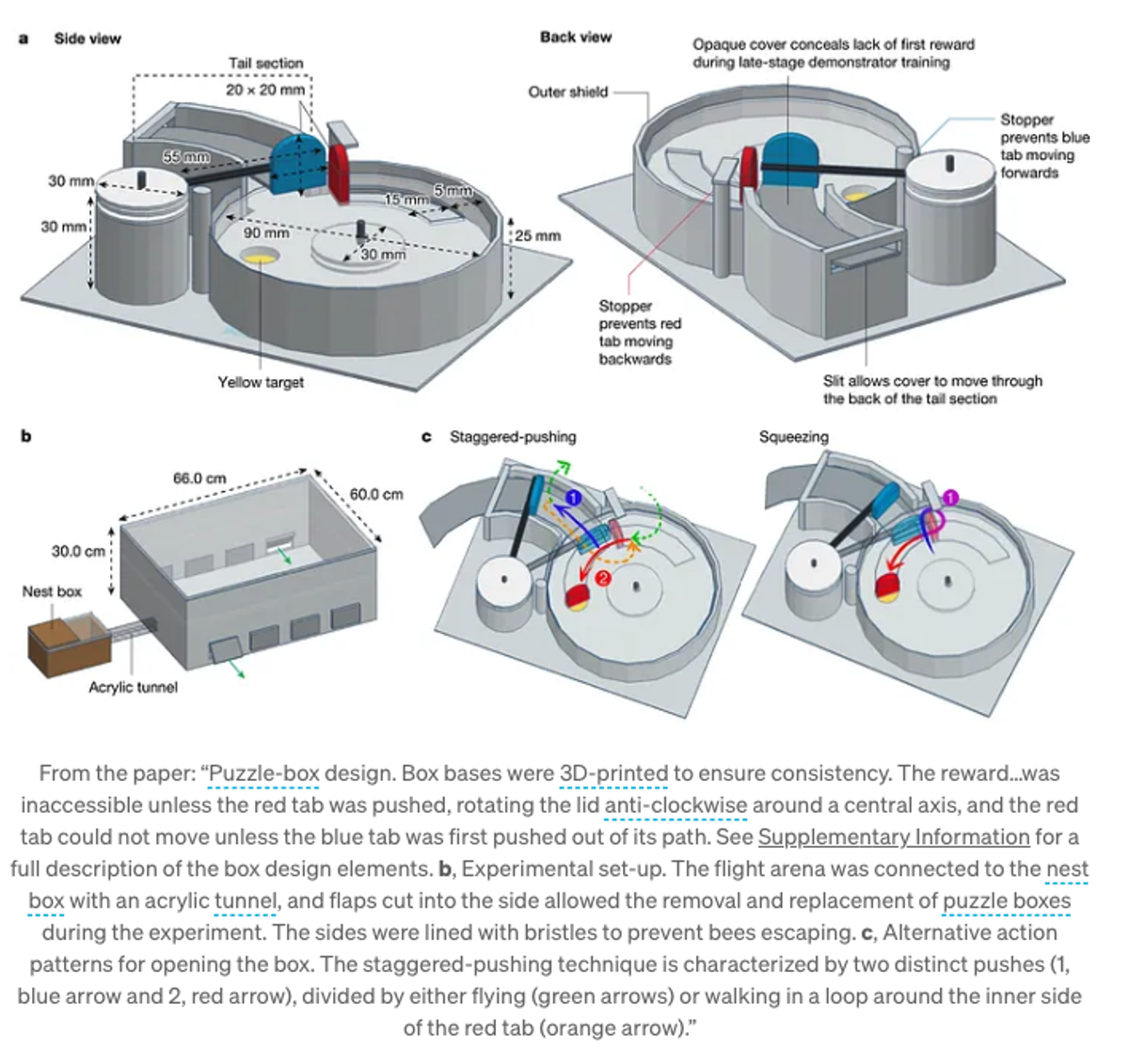

A little puzzle box with two tiny tabs, one red, one blue, sits in a clear plastic enclosure. One bumble bee approaches it while a second looks on from nearby. The first bee pushes the blue tab, revealing a reward, sweet sugar water, hidden beneath. Once the blue tab is pushed, the red one is free to move. The little explorer gives it a shove to reveal another compartment, also full of sugar water. What a lucky day!

Tomorrow, she’s not so lucky, there’s no sugar-water underneath the blue tab after she pushes it out of the way. But what about the red? It’s still there. She can have a treat after pushing the red tab, so she slides it aside and digs in. Still, the other bee watches on, seeing what she’s doing, storing it away for later.

When it’s the watcher’s turn to play with the puzzle, she squeezes the blue tab out of the way, loops around to the red, gives it a push, and her reward is revealed.

This may seem trivial. It’s just a two step puzzle. It hardly qualifies as a puzzle to us. But the researchers involved in this piece published in the journal Nature, see more. Much more. This could be the first sign of cumulative culture in a species other than humans.

What is cumulative culture?

I couldn’t have figured out how to type on my own, or prepare the coffee I’m currently sipping. Nor could I have built this chair, computer, even this wooden desk without thousands of years of cultural development behind me.Modern human life is the product of cumulative culture.

The discoveries and knowledge of each generation are passed down to the next and added to, letting us take advantage of things that we never could have learned independently. Our culture is built on behaviors and abilities so complex that none of us could learn them by ourselves in our lifetimes. Many anthropologists believe that this process drastically shaped our evolution and that it’s unique to humans. One of those beliefs may be wrong.

Let’s go back to the bees to see why.

Before getting to watch another bee work on the puzzle, our watcher bee couldn’t solve it on her own. Without the reward under the blue tab, she couldn’t learn to push the blue first, then the red. This two step process was too much for any bee to understand without training. To learn to solve the puzzle, the bumble bees needed a reward after each step.But the watcher bees, bees who saw another bee perform both steps and get rewarded each time, were able to do both steps without getting rewarded in between.

They saw what another bee was doing and learned.

Individual trial and error wasn’t enough for bumble bees to learn this two step box, they needed to learn it from another bee. Without this learning step, “no bee came close to opening even a single box, and their interest in the closed boxes plummeted with time,” wrote the researchers. The only way the bees could learn to open the two-step puzzle box was socially, with the help of another.

Every other example of cultural development we’ve seen in animals is simple enough that they could have learned it on their own — at least in theory. We’ve seen macaques washing food before eating it, New Caledonian crows making tools from leaves, and humpback whales changing their songs, all through methods of social learning and observation. They see another individual do it, try it themselves, and keep doing it. Even though they learned these things from watching one another, all of these behaviors were simple enough that the animals could have done it themselves without seeing another do it first. The animals sustain this behavior and pass it down generation to generation, but the behavior is not so complex that it would be impossible to learn on their own. What the bumble bees did was.

For bumble bees, this doesn’t mean much. Even though they’re capable of passing knowledge from bee to bee, the generational knowledge doesn’t add up. In bumble bee colonies, the founding queen and all the workers die every season. Only newly emerged, fertilized queens make it through the winter. These young queens don’t cross paths with enough other bees to have information passed down generationally. The culture may accumulate between the bees of the same generation, but does not make it to the next.

That’s the large dividing line between bees and say, humans. We’re able to pass our knowledge down and accumulate this culture across generations, not just within them. My dad learned from his mom and passed it on to me, and now the knowledge has spanned three generations. This isn’t available to bumble bees. The next group of bees will have to relearn this behavior all over again. But for other animals, we’re not yet sure.

Longer lived animals who live or mature in groups, like many whales, dolphins, chimpanzees, marmots, damselfish, and slower-maturing bird species like the harpy eagle, have more opportunities to pass culture down. Though this hasn’t been observed yet, it may be happening right under our noses all the time. We haven’t watched enough of these animals’ behavior to know which capabilities they have to learn from others and which they can pick up on their own.

Bees are easy to observe and study, other species are more difficult. The researchers point that out in the paper, “It is hard to see how one would even begin to approach such an experiment in a wild humpback whale. This does not mean that these animals are incapable of cumulative culture, or even that these examples do not represent it: it simply means that we cannot know for sure whether they do.” It’s possible that animals are doing this constantly, but we don’t have the body of research to know. Before this study was published, it was believed this behavior was unique to humans, so many researchers may not have even been looking for it. Now, they will be.

These little bees have shown that we’re not quite so unique as we thought. And that’s good, I think. We are part of the world, not separate from it. We came from it and exist within it, to it we shall return. Humans are unique and amazing, but just a little bit less than we thought we were.

Here’s the paper that originally shared this work:

Bridges, A. D., Royka, A., Wilson, T., Lockwood, C., Richter, J., Juusola, M., & Chittka, L. (2024).Bumblebees socially learn behaviour too complex to innovate alone.Nature, 627(8004), 572–578. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07126-4