Assistant Principal

Katrina Spicer - Wellbeing

Assistant Principal

Katrina Spicer - Wellbeing

Our School Captains, Vice School Captains and House Captains have selected the SWPBS Reward Options for Term 1. Students use the tokens that they have earned during the week for demonstrating positive behaviour, to vote for their favourite reward option. The option with the most votes at the end of the term will be the winner!

Junior School Reward Options (Prep, 1 & 2)

Senior School Reward Options (3, 4, 5 & 6)

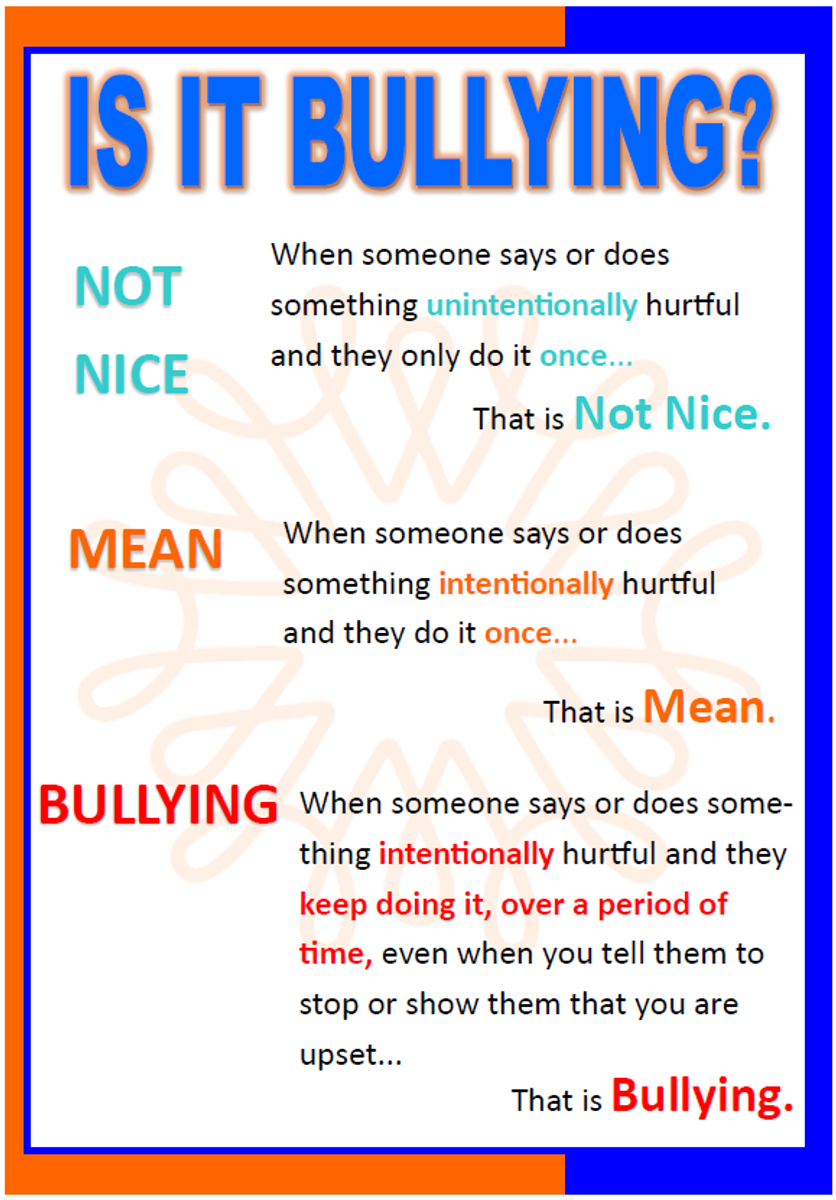

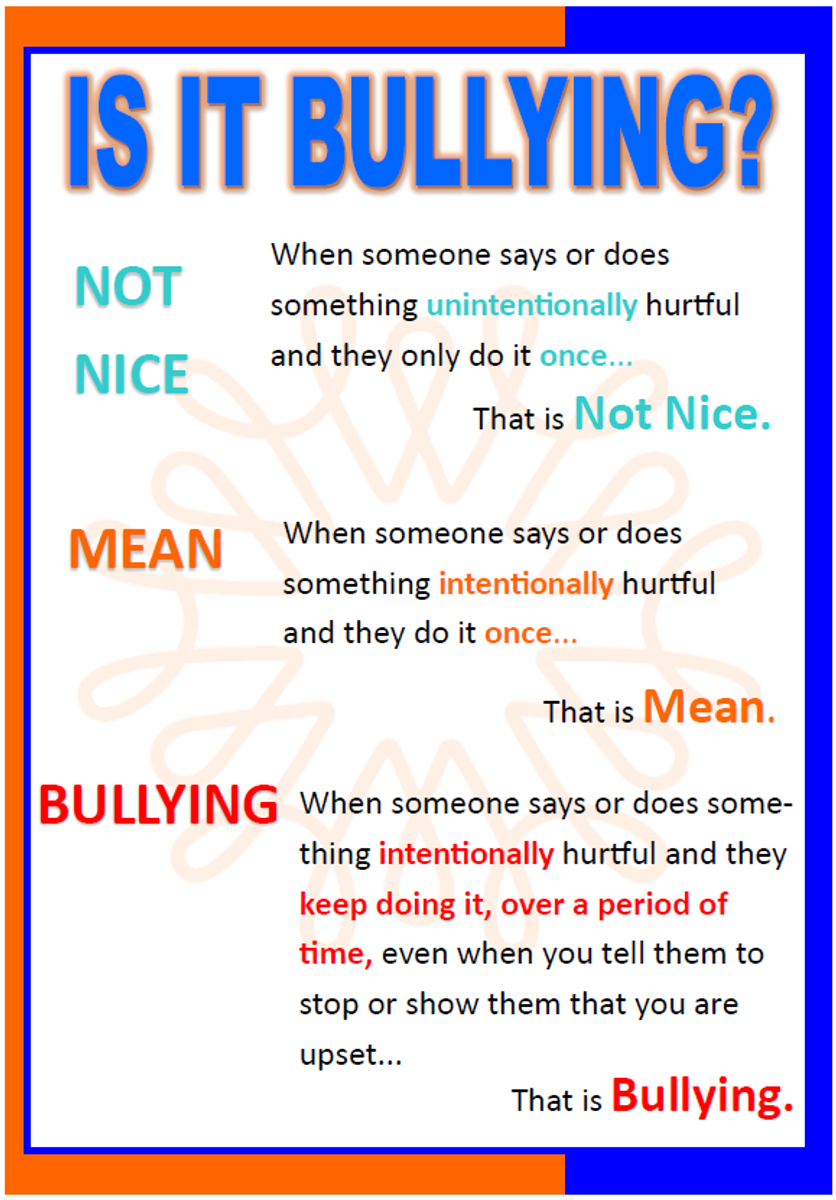

The word 'bully' is a powerful word that evokes images of harmful intent, power imbalance, fear and intimidation. This word is sometimes used by students and families when students have experienced unpleasant experiences at school.

The Merriam Webster dictionary definition of this word is: 'one who is habitually cruel, insulting, or threatening to others who are weaker, smaller, or in some way vulnerable.'

At WHPS we have clear, consistent messaging about what constitutes bullying. We teach our students that one unpleasant experience does not meet the definition of bullying, and that this behaviour could be described as 'Not Nice' or 'Mean'. Bullying is ongoing, targeted hurtful behaviour.

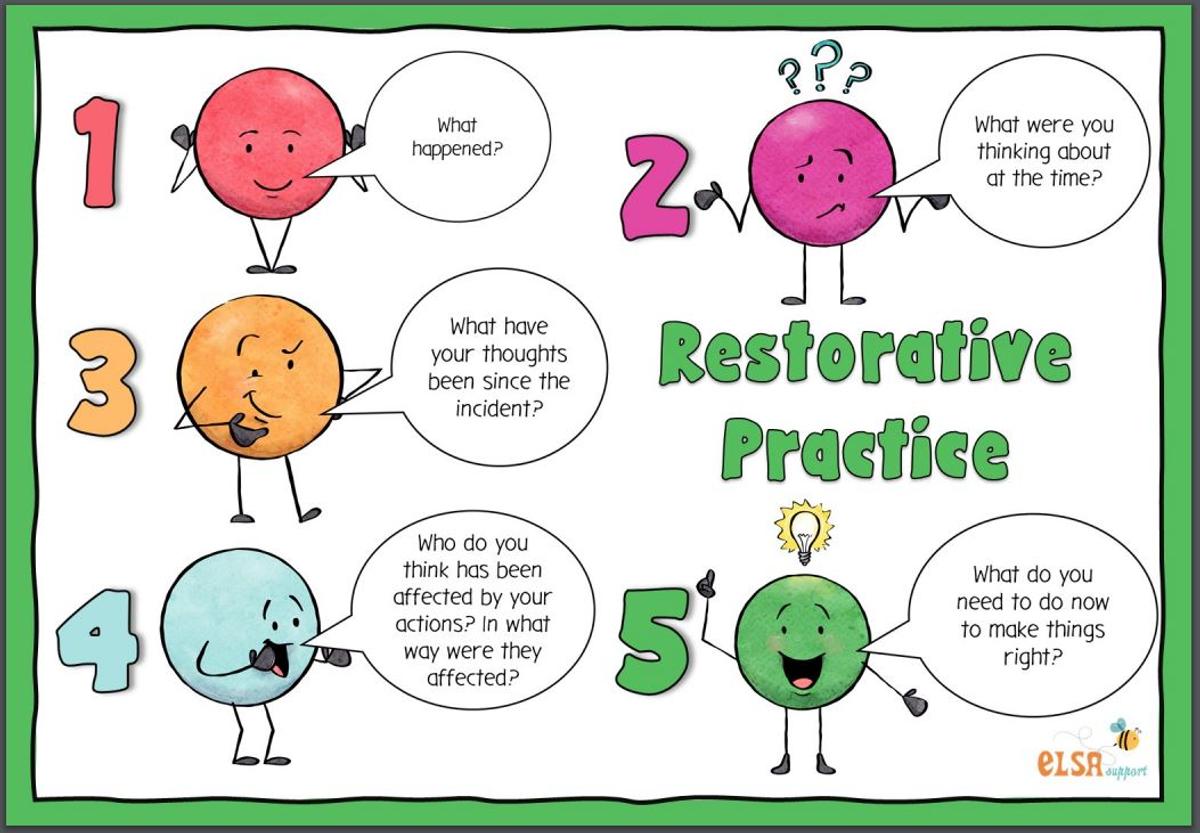

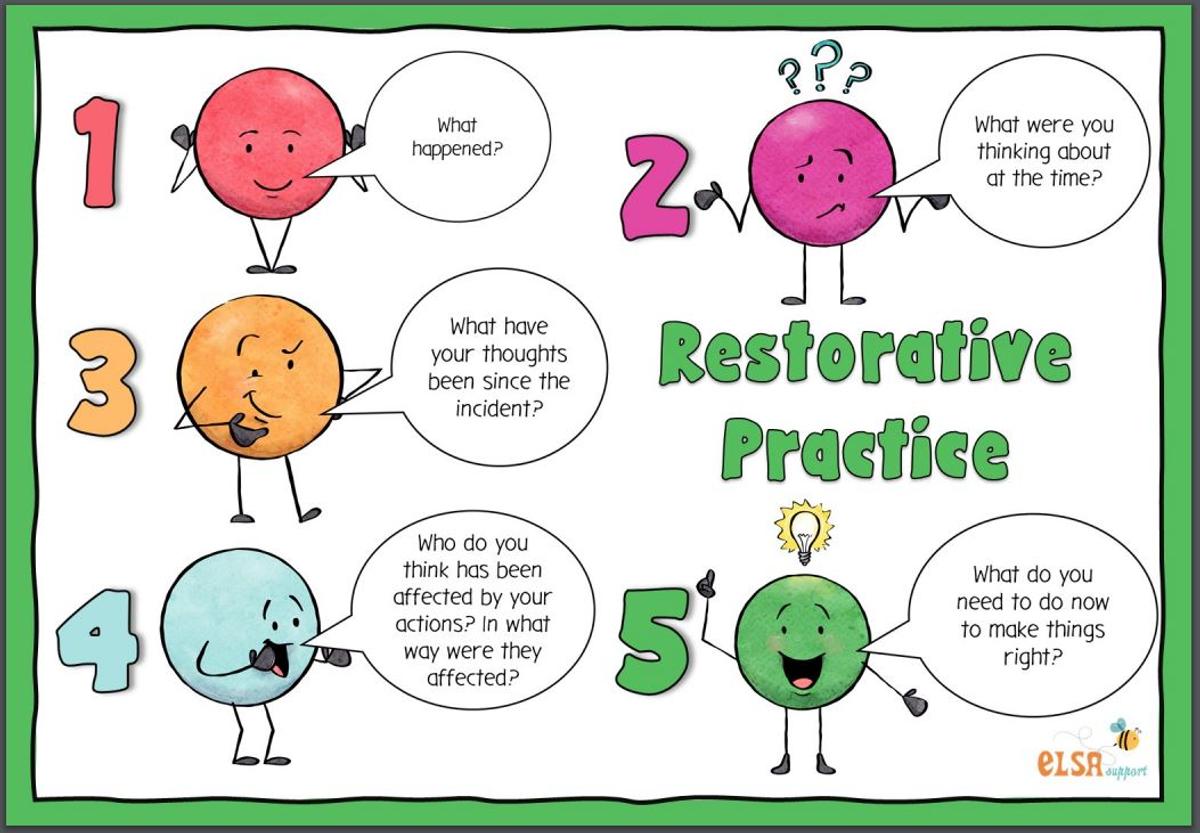

This poster is on display in every classroom and is used by teachers to assist with resolving playground and social issues. Having clear, consistent language around inappropriate behaviour helps our students to understand their own and other students' behaviour and assists school staff to manage such behaviours.

Restorative Practices

As our students develop their social skills, inevitably some students will make mistakes, behaving in ways that are hurtful or harmful to others. When mistakes like this occur at WHPS, we use a restorative approach to help heal the harm done and set things right.

A restorative approach differs from more punitive approaches to behaviour management, in that we focus on the harm done, and what must happen to set things right. Behaviour mistakes are managed in terms of how others have been affected and we aim to bring about a sense of remorse and restorative action on the part of the 'offender', and forgiveness by the 'victim'.

Research shows that a restorative approach to behavioural mistakes results in more lasting behavioural change than authoritarian measures, and improved relationships between those who harm, and those who have been harmed.

A typical restorative chat would involve all concerned parties. Everybody has the opportunity to explain their side of the story, and those affected are able to say how they would like the situation to be resolved. Usually, children simply ask for an apology and sometimes, if they are not feeling safe around someone, they might ask for the 'offender' to be withdrawn from the playground. 'Offenders' are induced to feel remorse and empathy for those affected, and we aim to mend broken relationships.

Staff members who run restorative chats will follow a set structure or script, to guide the discussion. The majority of behaviour mistakes at WHPS are managed through this restorative process.

A restorative approach may not be appropriate for significant, major incidents. In such cases, students will be referred immediately to school leadership.

In primary school it was bike rides, cubby houses, climbing trees, playing marbles, jumping on the trampoline, and being outside – always outside... and it was almost always with my best buddies: Andy Lucas, Ben and Jay Walter, Richard and Ian Duddy (I’ve never done a shoutout to my old buddies before...but here it is, after so many years).

In my teens, it was ultra - long bike rides (of 50 kms or more – that was a lot for a 15-year-old who wasn’t a cyclist), surfing, skateboarding, and exploring the bush in the mountain behind my house.

I was lucky to grow up in the 80s.

It was probably the last decade where kids had the sort of freedom that I had. With every decade since, research shows that children have become more restricted, more structured, and less able to play and explore in their neighbourhoods away from adults. It’s well documented that the amount of time available to kids for free play is declining.

Unfortunately, that’s not the only thing that has changed since the 80s.

In 1980, less than 10 in 100,000 teen boys died by suicide, and for girls it was only 2 in 100,000. By 2000, it had increased to 13 in 100,000 for teen boys and 6 in 100,000 for teen girls. While in 2020, the number of suicides among teen girls remained steady, for our teen boys it jumped again to 17 in every 100,000.

Behind those stark numbers is the equally alarming doubling in the prevalence of anxiety and depression in our teens and young adults over the last 15 years.

Why?

Screens are the most commonly-blamed culprit. While the scientists behind this argument make a compelling argument, there are alternative explanations. One is that parents are more controlling than ever before. A related idea is that children don’t get to play anymore.

I’m not the only one who believes that the decline in free play is a contributing cause. Kids are constantly being pulled away from the opportunity to engage in real life, physical (and outdoor) play because:

The problem with reducing play time is that play is a direct source of happiness for our children. Studies show that kids prefer outdoor play with friends to screen based activities, and outdoor play is consistently ranked by parents as the activity that makes their kids the happiest – if we can get them to do it!

What exactly is it about play that has such a big impact on wellbeing?

Play satisfies all of our basic psychological needs. By definition, play is self-directed. Play is the vehicle through which kids build skills. Play is how children make friends.

As parents, how can we give our children the freedom to play?

1. Strengthen autonomy – allow our kids more choice in how they spend their time. Cut back on structured extracurriculars to enable them more time for free play. Move away from adult-directed activities to unsupervised play (as developmentally appropriate).

2. Build competence – set up the environment with equipment for open ended play. Open ended toys build competence because there is no right way to use them, and the materials can be modified to meet the level of play that your child is ready for.

3. Relatedness – build a community of people your kid can play with easily. Things like introducing your family to other families in the neighbourhood is a great start. Giving our kids an idyllic childhood with freedom to play and explore isn’t just good for them now. It helps them build the resilience they need for healthy adulthood too.

Our school subscription to Happy Families allows access to the Happy Families website to all members of our school community.

Families can access the Happy Families website at: https://schools.happyfamilies.com.au/login/whps

Password: happywhps

Katrina Spicer

Assistant Principal for Wellbeing and Inclusion