Teaching & Learning Page:

Web Pages:

Techie Tips:

7 Easy Ways To Edit PDFs Directly From Your Mac

Preview is a great (and free) PDF editor, it turns out.

The best PDF editor on your Mac is the one that ships with your Mac. I'm talking about Preview, an app whose name hides its versatility. It can do a lot more than open different types of files. For PDFs, it's as good as most free PDF editors.

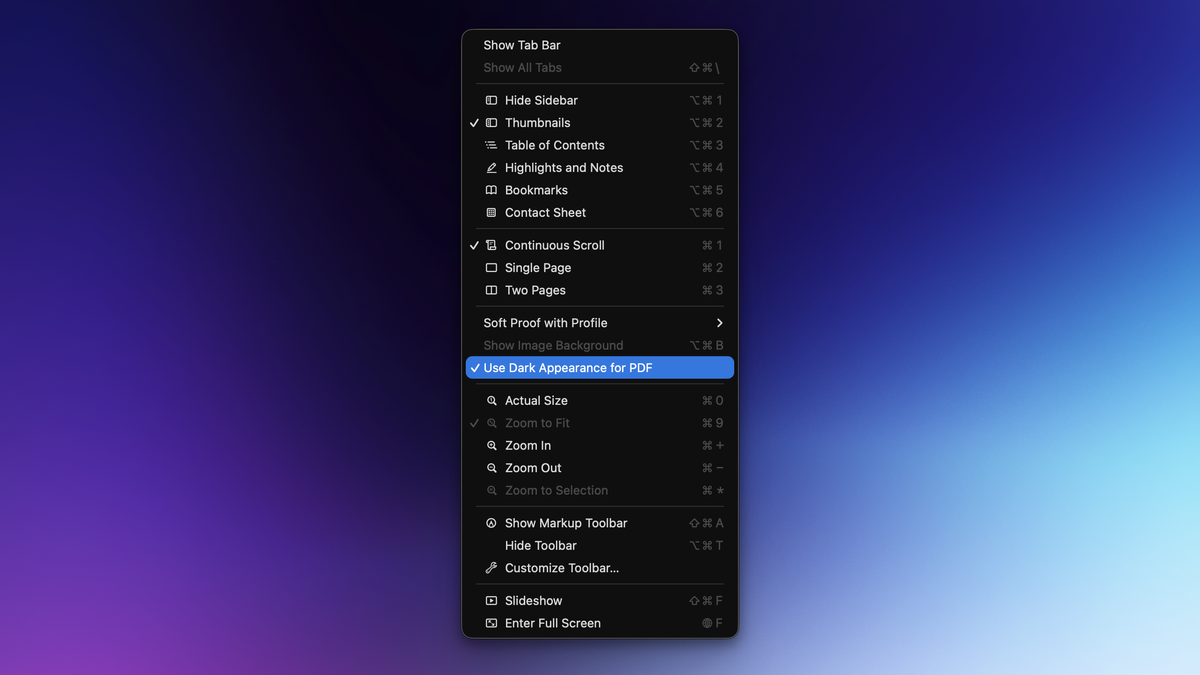

Enable dark mode for easier reading

In macOS 26 Tahoe, Preview now lets you enable dark mode for any PDF, so I no longer have to deal with bright white backgrounds when I open a PDF.

To use this feature, open a PDF file in Preview on your Mac. Now click the View button in the menu bar at the top, then select Use Dark Appearance for PDF.

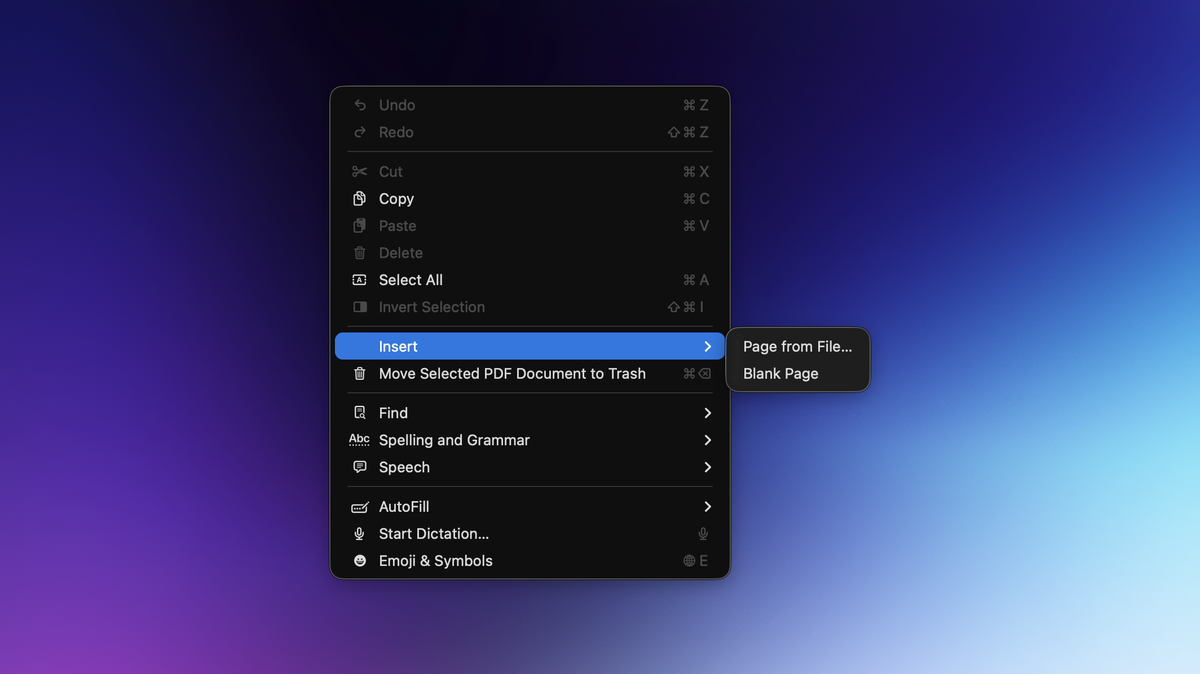

Insert pages in a PDF file

Preview lets you easily add pages to a PDF file. You can either add a blank page or insert a page from a different file. To use this feature, open a PDF file in Preview and go to Edit > Insert. You can either choose Blank Page or Page from File….

The option to insert a blank page in the PDF is self-explanatory. If you want to insert a page from a different file, there are different ways to do so. The option in the Edit menu will directly insert the whole PDF or image file you select into your PDF. This is fine when you're selecting a single-page PDF to merge into a larger file, but it's not ideal if you want to add just one page from a 50-page document. If you're trying to do this, add pages by opening two PDF files side-by-side in Preview and dragging pages from the first to the second PDF file.

If the sidebar is hidden in Preview, go to View > Thumbnails. You can now drag the thumbnail from one sidebar to another with ease.

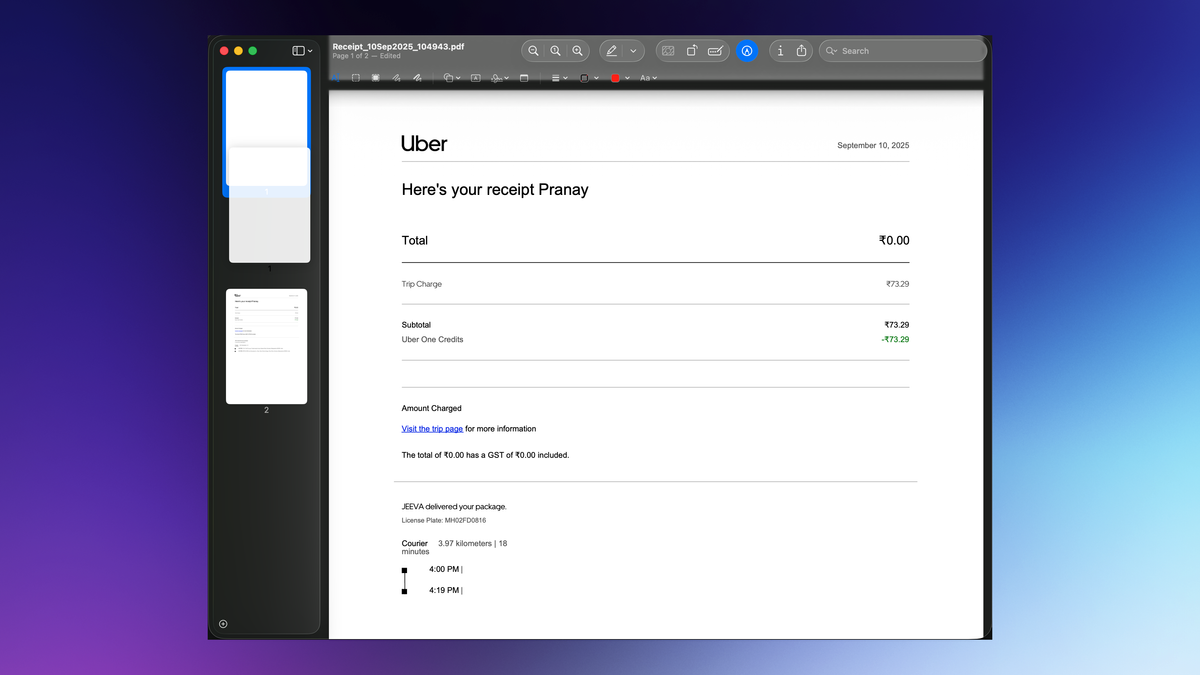

Reorder pages in a PDF

In Preview, to change the order of pages in a PDF file, drag and drop the thumbnails in the sidebar to rearrange them. It's quite smooth and intuitive, and you'll be able to get the job done pretty quickly.

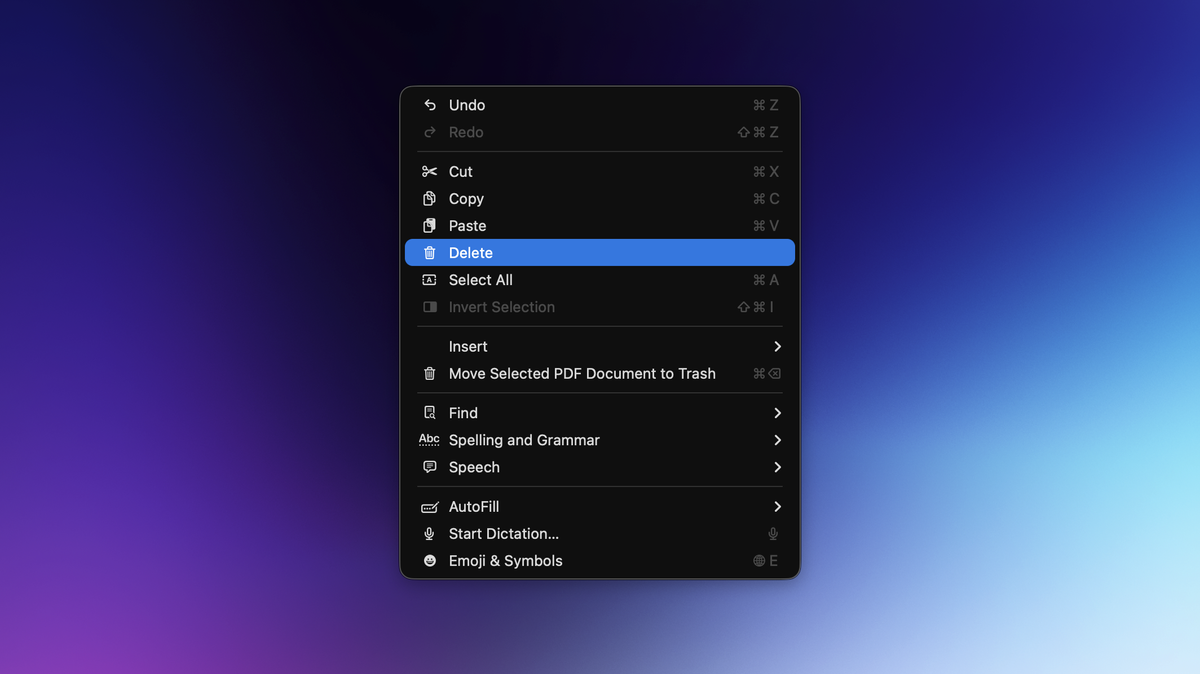

Delete pages from a PDF file

Preview has a built-in page deletion feature, too. Once again, open a PDF in Preview, select a page in the sidebar, and press the Delete button to remove it from your PDF. This option is also available under Edit > Delete.

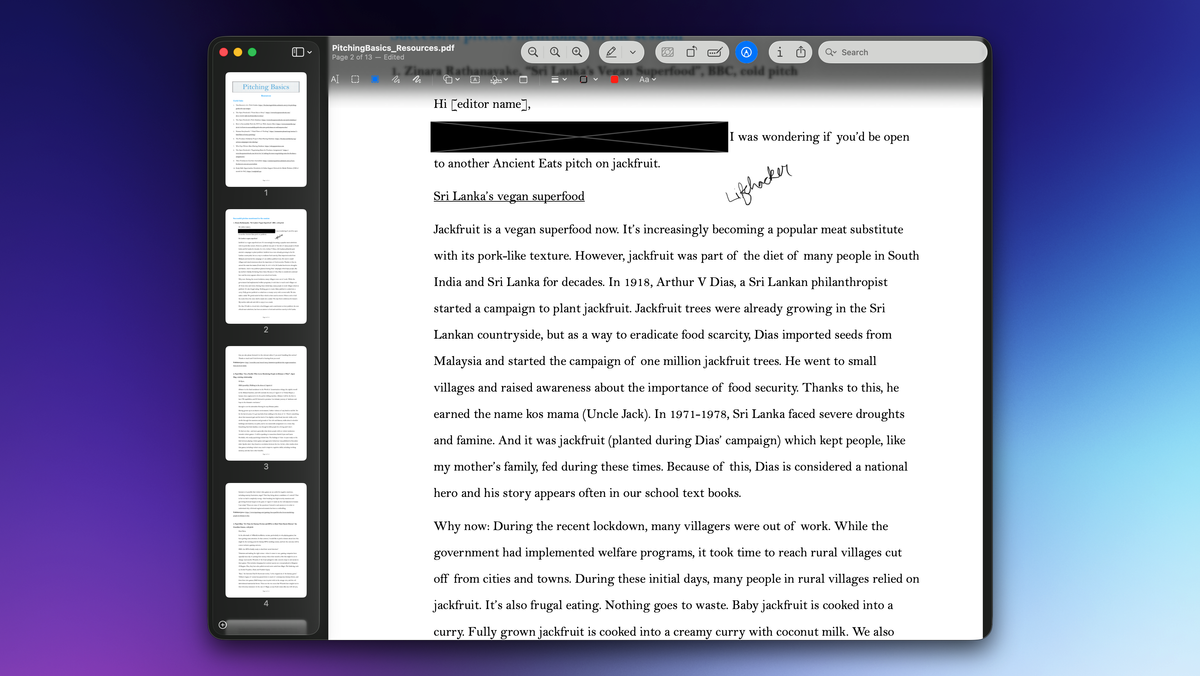

Annotate, edit, and redact text in a PDF file

You can use basic markup tools to add, select, edit, and redact text in Preview. These tools, along with options to annotate and sign PDFs, are available in the Markup Toolbar in Preview for Mac. To access these tools, open any PDF in Preview and click the pencil icon in the toolbar. Alternatively, you can go to View > Show Markup Toolbar. These tools are more than sufficient for quick edits to PDF documents.

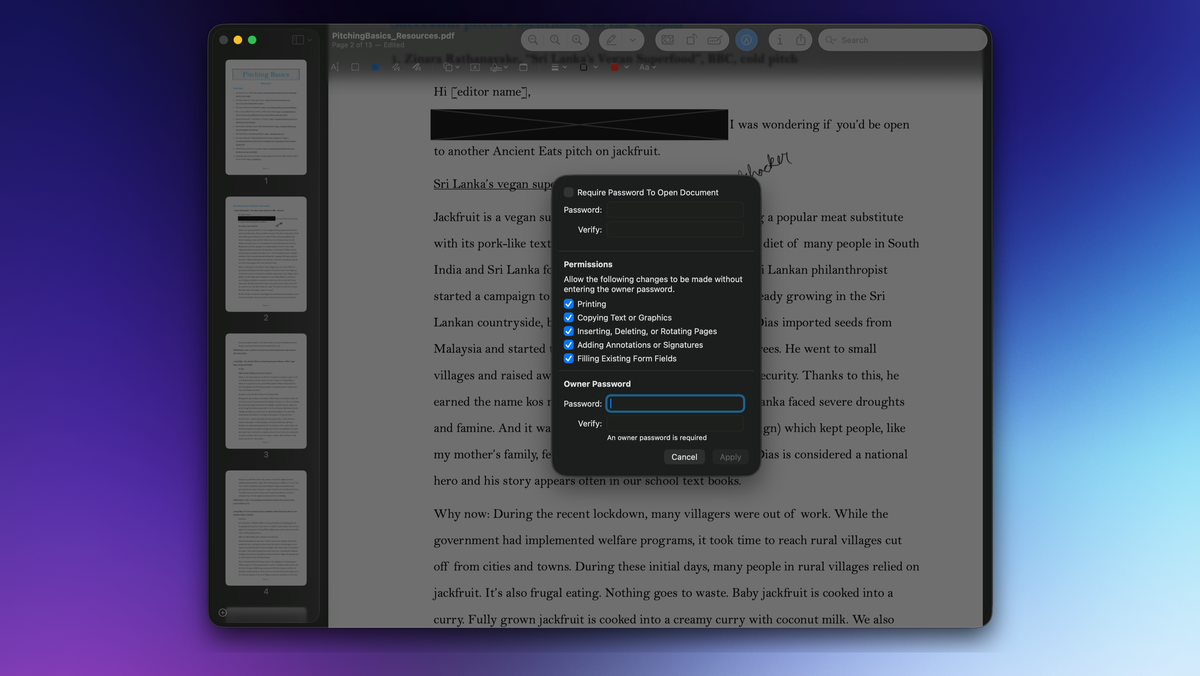

Add a PDF password

You can use Preview to add a password to a PDF file or to remove passwords from a file. To add a password to the PDF file you're viewing in Preview, go to File > Edit Permissions, and check the box labelled Require Password to Open Document. Once you've added and confirmed the password, you'll also have to add an owner password to the document. The owner password lets you restrict others from making changes to the PDF, printing it, or taking other actions. Ideally, it should be different from the password used to open the PDF file. After adding both passwords, click Apply to confirm the changes.

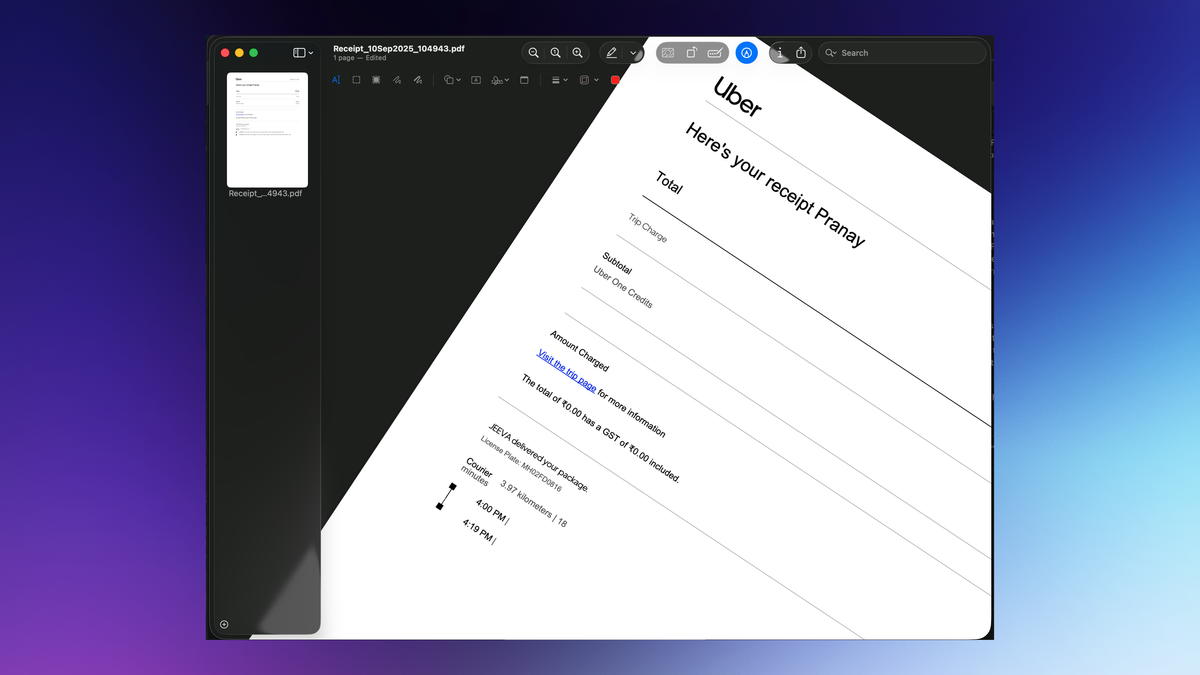

Rotate pages in a PDF

Credit: Pranay Parab

Sometimes, PDF files arrive with an unusable orientation—e.g., portrait pages scanned in landscape mode. In such cases, you can use Preview to rotate the pages of a PDF. Just go to the page you want to rotate and press Command-L to rotate it left or Command-R to rotate it right. Fun fact: You can also do the same thing using your trackpad. Use two fingers to mimic a rotating motion, and you'll see that the page of the PDF file rotates to the left or the right.

These options are also available under the Tools menu. Over there, you'll also find options to flip a page horizontally or vertically, as well as a feature that removes the background from a PDF page.

Activate “Move Focus to Next Window” for Multi-Window Apps

Command + K’ — Command + K’ brings up the link box in text editors and emails.

‘Highlight text’ → ‘Command + K’ and ‘Paste link’.

The “K” is for “linK,” because ‘Command + L’ was already taken.

Spotlight isn’t just a launcher anymore — it is now becoming a command center.

Press “Command + 3” and you will enter the “Actions Mode”.

From here, you can do things like:

Send a message

Create a note

Trigger a Shortcut

With Command + 4 in Spotlight, you now get access to your Clipboard History — including text, images, and other copied content.

With this, you can:

Click an item to re-copy it

Right-click for more options

Paste without retyping or switching windows

Sketches:

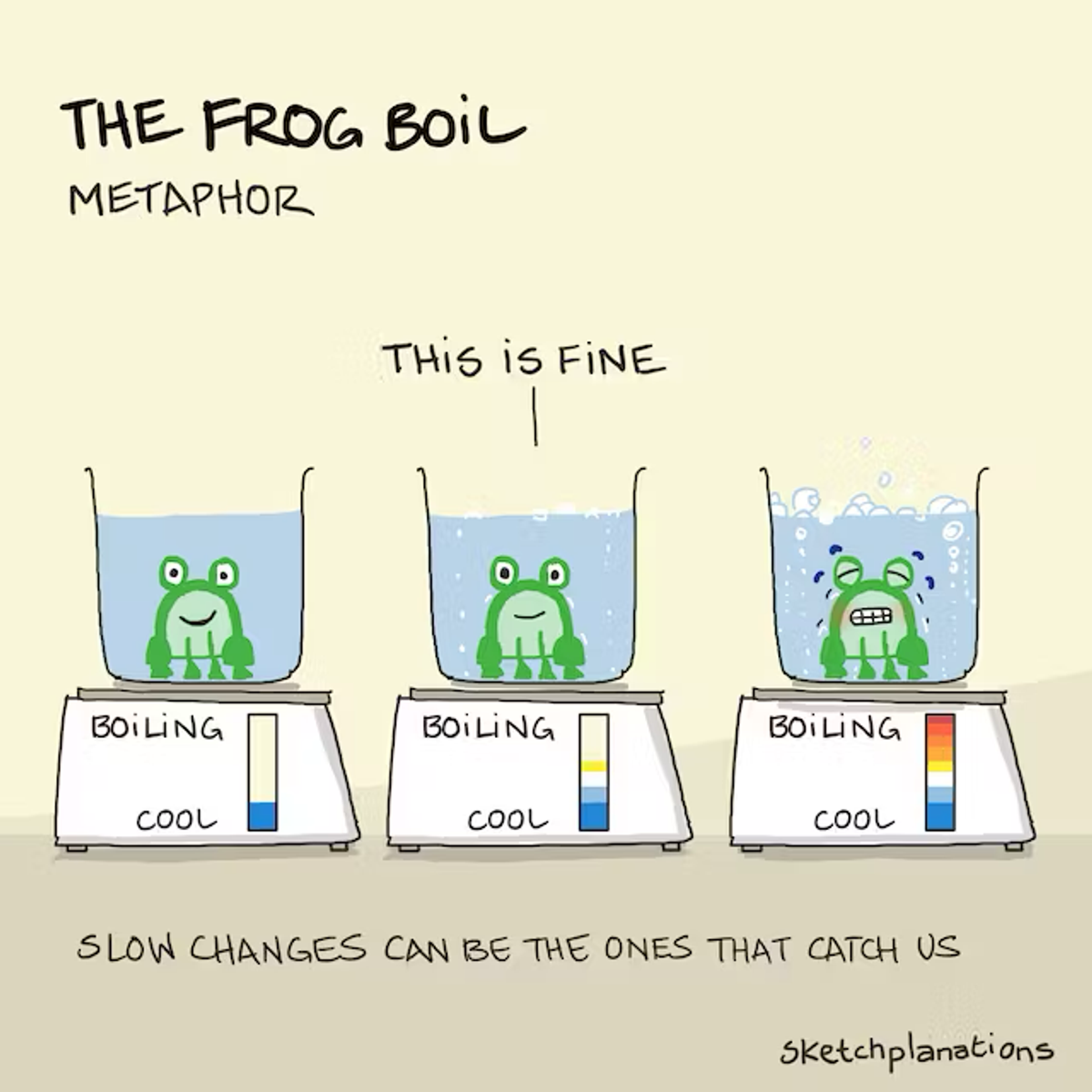

The frog boil metaphor

The frog boil metaphor illustrates how easy it is to miss small changes that build up over time until it's too late. The scenario, as told, is that of a poor frog who would leap away from hot water but, if put into cooler water that is gradually warmed, won't respond in time to getting boiled.

As a metaphor, it describes a powerful and pernicious shortcoming in how we perceive the world. A student kitchen that gets messy mug-by-mug, a business with gradually slowing sales, a river that is slowly polluted, a road that gets busier each day, a bay that sees fewer fish each year, content that drifts, cancer that slowly spreads, a story or behaviour that becomes normal, a website that gets slower feature-by-feature, or a climate that slowly warms are all cases where we may not be happy where we end up, but we didn't notice how we got there.

It's hard to respond to gradual change, especially when it spans generations. Jared Diamond called it out as a potential fate of the Easter Islanders and how they could have cut down the last tree. One barnacle is nothing, but many barnacles can cause significant headaches for big ships.

Fortunately, there's a flip side. Many, many things are getting better without us realising. Small positive changes, such as in attitudes, education, or healthcare, add up over time—the Destiny Instinct can mislead us. Fast and slow layers make a system, like a forest, more robust. Getting 1% better each day leads to a 37x improvement in a year. And enough molehills can make a mountain.

—

What a frog does, in this case, is not, apparently, true—don't try it—it's much better as a metaphor, not an experiment.

Article:

How do we learn? What should that say about how we teach?

When I first asked myself this question, it sounded like a pedantic query. Over three decades of teaching, this line of questioning led me from one rabbit hole to another. In 2023, as I began designing a new course on computational thinking, the questions merged. On the surface, a more interesting and relevant theme. Can machines think? And how is that different from how we think?

Large Language Models (LLMs) solve for occurrences, frequencies, and averages, not outliers, exceptions, or contrarian opinions. There are applications where this is useful. There are instances where it isn’t.

Successful careers are based on exceptional work and insights, not averages.

Consensus makes LLMs a valuable tool for data processing, enabling them to see relationships in data and forecast future behaviour based on patterns discerned. They are good at repetitive mechanical tasks, summarising, and converging to mean results that minimise errors and distance between predicted and actual values.

The Felin and Holweg Theory is all you need; the paper indirectly presents a new test for intelligence. The Felin and Holweg test proposes that the world has structure. A model must represent the world in a form that allows it to reflect on that structure. Reflection ultimately leads to self-awareness; without reflection, there is no intelligence.

The human mind is forward-looking and can theorise about underlying drivers that may help solve a specific problem. They can follow up on that theory by directed experimentation that may validate or invalidate the original explanation or belief system, as well as update it based on confirming or conflicting observations.

In times of extreme change, it is helpful to focus on what doesn’t change. Critical thinking that would lead one to stand against conventional wisdom was rare in the 1600s and 1900s. It is just as rare in 2025 and is likely to remain rare in 2050. If we can teach our students how to think critically, they will do well irrespective of the century they find themselves in.

One side benefit of critical thinking is the ability to distinguish between delusions and ideas ahead of their time.

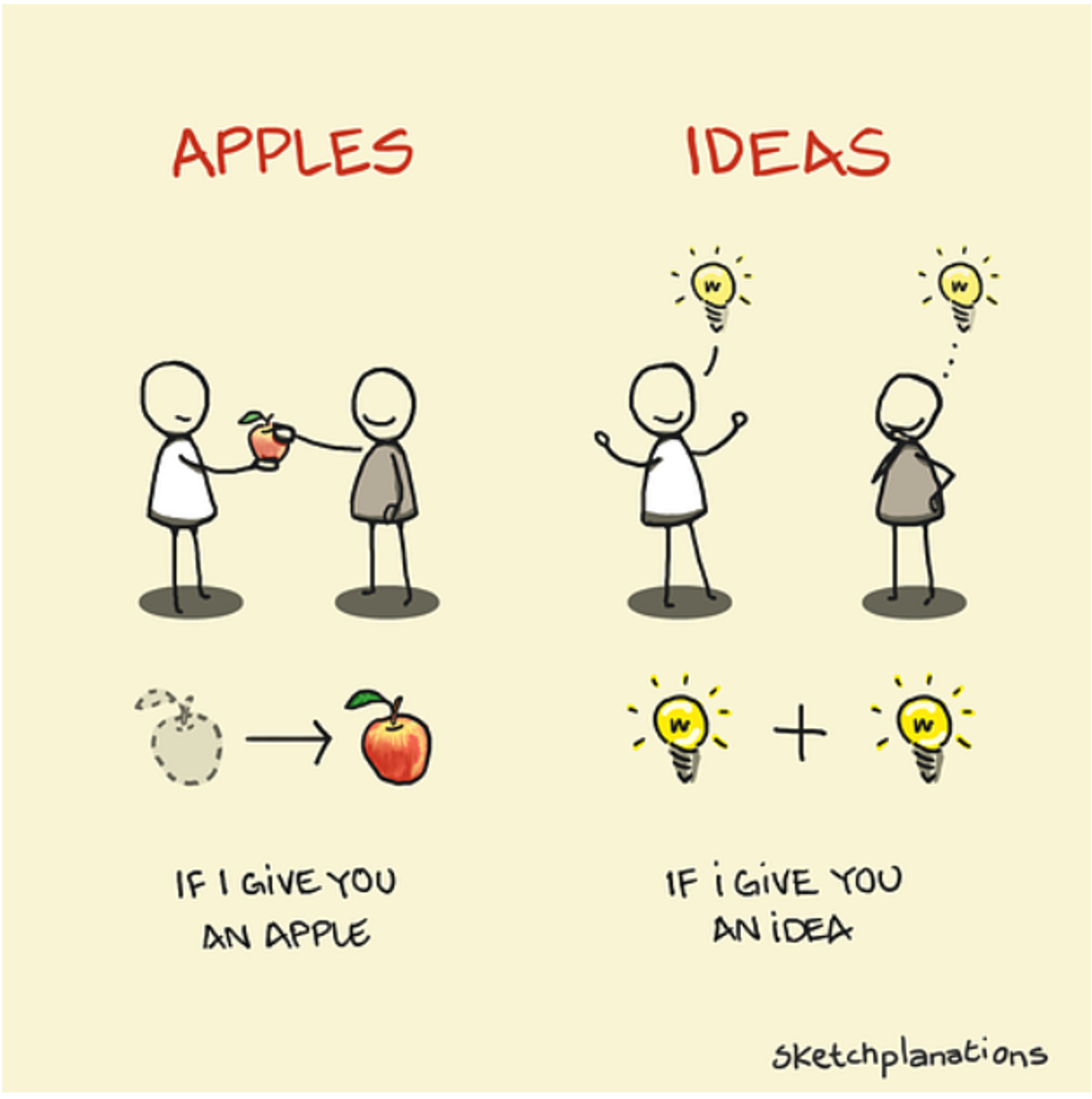

Apples and Ideas

Ideas don't behave the same as apples

“If you have an apple and I have an apple and we exchange apples, then you and I will still each have one apple. But if you have an idea and I have an idea and we exchange these ideas, then each of us will have two ideas.”

This quote, commonly attributed to George Bernard Shaw, though probably not from him, highlights one of the lovely things about ideas. They behave differently from physical things. They’re not exclusive; they’re additive and abundant.

Ideas Don’t Behave the Same as Apples

Though we talk about intellectual property, ideas don’t behave like property in the usual sense. One of the simplest ways to see the difference between ideas and objects is to look at what happens when we share them.

I can give you an idea, and we both have the idea, but if I give you my apple, then I no longer have one. This also makes ideas very hard to take back once they are out. Ideas are harder to control than objects.

Because ideas are abstract—they don’t exist in a physical form—we use conceptual metaphor to talk and reason about them. What follows are some of my favourite examples of how we think about ideas, drawn primarily from Philosophy in the Flesh and the very readable Metaphors We Live By by George Lakoff and Mark Johnson.

The Ideas Are Objects Metaphor

Metaphors are how we talk about abstract concepts, like an idea. And the Ideas Are Objects metaphor is one of the most common ways we understand them. This means that a lot of how we talk about apples and ideas overlap.

So I can:

- give you an idea (or an apple), and maybe you’ll

- grasp it, or perhaps it might

- go over your head

Ideas can be:

- solid or weak

- shared or hoarded

- fragile or bulletproof

- cheap or gold

Thinking Is Object Manipulation

Because you can examine objects and manipulate them, we have the metaphor Thinking Is Object Manipulation.

When you think about an idea, you might:

- play with it

- toss it around

- see if it sticks

- share it with others

- try to break it

When you communicate with someone, you exchange ideas.

- you can give an idea

- get an idea across

Together with the Mind Is a Body metaphor (mental exercise), a teacher might try to:

- put an idea into students’ minds

- fill them up during the term

- see how much they’ve retained

And I’ve certainly employed cramming before a test.

Because Understanding Is Grasping—having an idea under control—when you don’t understand something, it might:

- be slippery

- resist definition—has no shape

- be beyond your grasp

As Thinking Is Object Manipulation, you can work on an idea:

- reshape it

- craft it

- fashion it

- analyse it by taking it apart

- deconstruct it

Together with Knowing Is Seeing, we can:

- Turn an idea over to see both sides of it

- hold it up to scrutiny

- shine a light on it

- put it under the microscope

Ideas Are Food, and Acquiring Ideas Is Eating

Another fun and common metaphor for ideas is rather more like apples. If the Mind Is a Body, then we need to feed it healthy, nutritious food. I like to think readers of Sketchplanations have an insatiable curiosity. In much of our reasoning, then, ideas are a special kind of object—they are our food for thought.

Unhelpful ideas are unhealthy, and helpful ideas are healthy, so they might be:

- raw

- fresh

- half-baked

- sweet

Or an idea might be:

- rotten

- disgusting or unsavoury

- unpalatable

- hard to digest

Or they might:

- smell fishy

- leave a bad taste in your mouth

Or perhaps they need to be:

- put on the back burner

- chewed on for a while

- sugar-coated

Significant ideas are:

- meaty

- something to chew on

- let stew for a while

So What Are Ideas Really Like?

So, given all this talk about Ideas As Objects, it’s easy to assume that ideas should behave like them. But before they take on a physical form — say, as a building or product — they don’t behave the same as objects.

Hopefully, this sketch conveys this idea to you while keeping it with me, too.

I think a more suitable conceptualisation is the magical powers of software with its infinite copy/paste. As software becomes more of our daily experience, we might gradually adopt more accurate metaphors for how ideas actually behave.

These are not the only metaphors we use across languages for understanding and reasoning about ideas and thinking, Ideas Are Locations, and Thinking Is Moving in particular (“I don’t follow you”). There are many. Do check out Metaphors We Live By if you’re curious for more (or Philosophy in the Flesh if you really want to get stuck in).

May you absorb lots of great ideas this week, as well as make a few tangible,

Jono

Book Recommendation: