Just A Thought:

The Listening Triangle

Mindfully Slowing down the conversation

Daniel Stillman

Lately, I’ve been hearing lots of friends and colleagues talk about slowing down a bit for the summer.

If it’s summer where you are, and you have the means, that’s an awesome choice

For example, if you’re in the Northeast of the United States of America the peaches are awesome right now...and such delicacies deserve to be savored slowly, far away from the glow of a screen.

Slowing down doesn’t just mean taking time away from work, we can slow down during work, too.

But I don’t mean slacking off for a nap, although plenty of research says that’s an awesome idea.

Slowing Down the Conversation

What would it feel like to give an issue a bit more breathing room?

What would it feel like to solve one key challenge instead of tackling several challenges during a meeting?

What if we stretched out the creative process, just a bit, and came up with one more idea before we started choosing the best way forward?

What if we dropped in, slowed down, and really listened to someone, before moving the conversation forward?

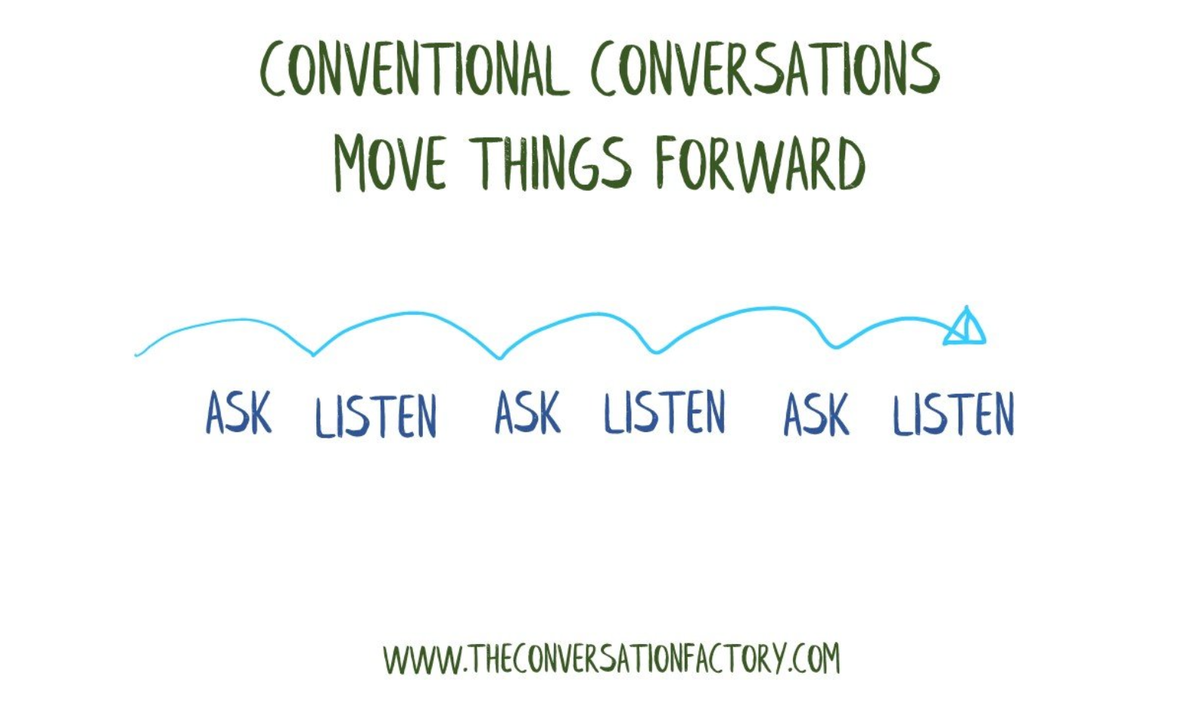

Conventional Conversations move things forward

In conventional conversations, we often ask a question, hear the answer and then move on to the next questions we have in our pockets. We assume that the answer we heard is sufficient, and that it resembles what the person actually meant to say. Rapid fire! Let’s move this convo along, people!

The fact is, while folks can speak around 150 words per minute, we think at the rate of thousands of words per minute.

What does that mean in practical terms? No one can ever say all they mean to.

Plus, most of us, when we’re meant to be listening, also tend to think, even just a little bit about the next question, or how we’ll respond.

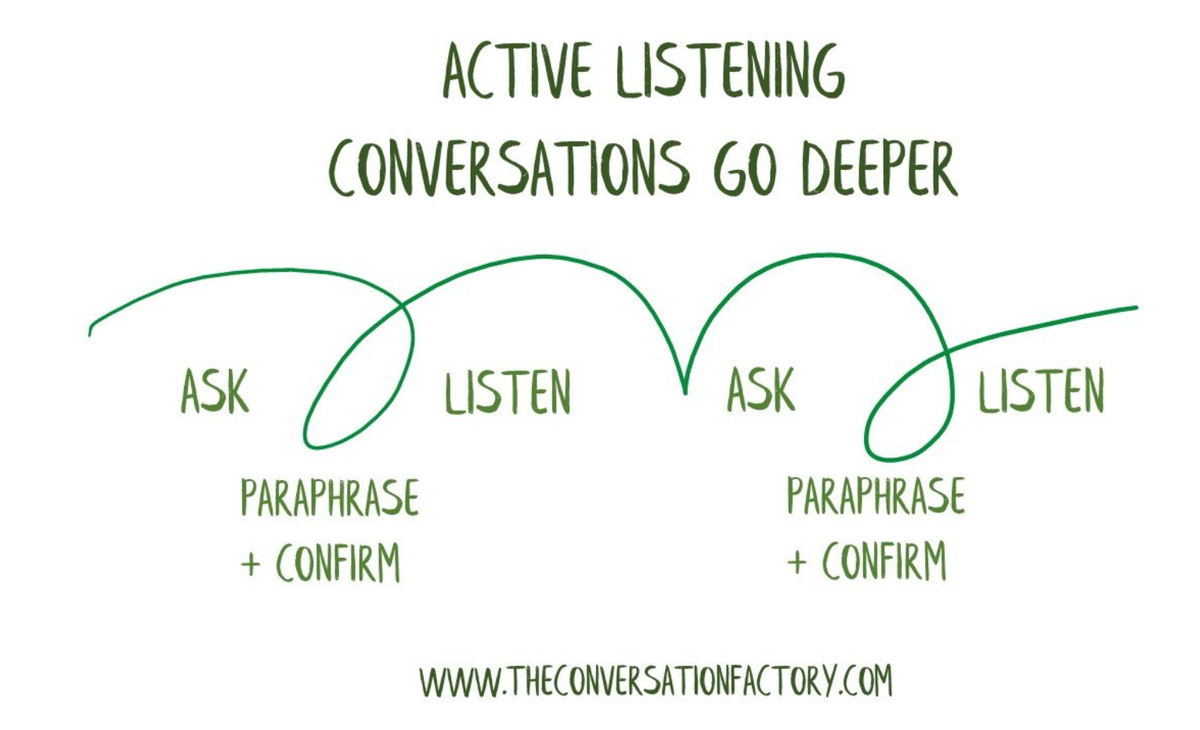

Active Listening is a great start.

Paraphrase and confirm! It’s like looping back and “double stitching” each thread of the conversation instead of moving forward in lockstep.

Active Listening Conversations go deeper

But the listening triangle goes one step even deeper!

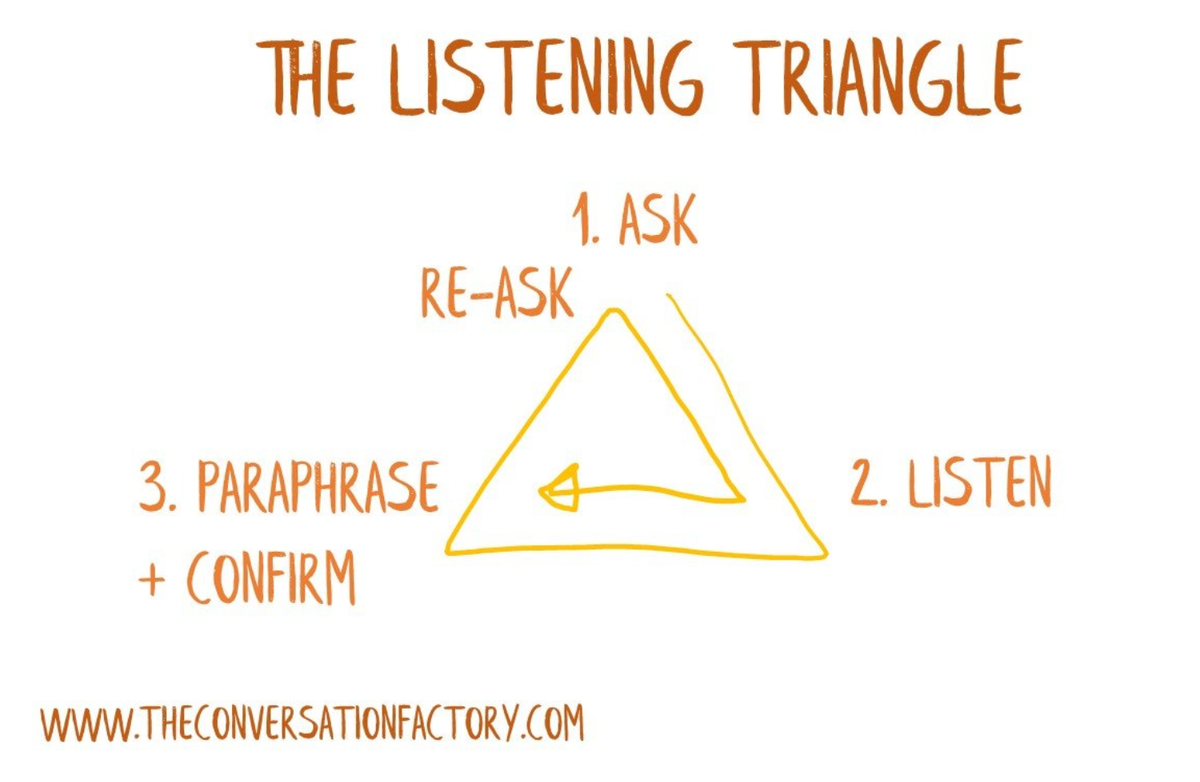

Triangulation is the process of finding out where you really are in a territory by taking a series of measurements. This approach, applied to listening, was recommended in an HBR article about managing a polarized workforce.

But this listening mental model works well when you want to cool down any heated conversation, or just slow things down for the summer.

Here are the basic steps:

1. Ask a real, powerful question.

2. Actively listen, ie, paraphrase and confirm that you got it right.

3. Re-ask. Don’t move on to another topic. Shift your question just a little bit to dive one step deeper and help triangulate your understanding of the person’s position.

I like to draw the Listening triangle like above, almost like a spiral, going inwards. Instead of moving the conversation forward, we’re taking it deeper, into the heart of the matter.

The authors of the HBR article suggest that the listening triangle can help you listen to understand, not just to respond, which can foster empathy and reduce polarized conversations.

This mode of relating to others can be transformative.

Slowing down your responses by re-asking can also ensure that your assumptions about someone’s beliefs are anchored in reality, not your biases or first reactions..

The listening triangle can also help someone feel really, really deeply heard. I love to use the listening triangle in my coaching conversations.

I am nothing special, of this I am sure. I am a common man with common thoughts and I’ve led a common life. There are no monuments dedicated to me and my name will soon be forgotten, but I’ve loved another with all my heart and soul, and to me, this has always been enough.

Nicholas Sparks

The following text is passage from "Citizenship in a Republic", a speech given by the former President of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt, at the Sorbonne in Paris, France on April 23, 1910.

The Man in the Arena

It is not the critic who counts, not the man who points out how the strong man stumbled, or where the doer of deeds could have done better.

The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena;

whose face is marred by the dust and sweat and blood;

who strives valiantly; who errs and comes short again and again;

who knows the great enthusiasms, the great devotions and spends himself in a worthy cause;

who at the best, knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who, at worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly;

so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who know neither victory nor defeat.