Learning Focus

As a school we get inundated with data. Our teachers are constantly collecting information from our students about their learning - what’s working, what’s not, what goals need to be set - you would be amazed to learn of all that goes into giving your child those little dots on their school reports. But schools also collect data through surveys from their teachers (the School Staff Survey), their students (the Attitude to School Survey for Year 4-6 students) and families (the Parent Opinion Survey). David, our recently retired principal, always told us not to read too much into these surveys.

But David isn’t here anymore (though, I have a feeling he is still reading the newsletter).

Some people (maybe most people?) don’t get particularly fascinated by data like I do - so I apologise if you are reading this and becoming a little disengaged - but data can be a great way to celebrate the amazing things that are happening in our school, but also shine a light on what can be improved.

For example, here is some data from our 2023 Parent Opinion Survey that we can celebrate. In the area of School pride and confidence (confidence in NLPS’ ability to provide a good standard of education to children) when compared to schools that are similar to us (similar size and demographic) and the state, our data is outstanding. This particular area has improved year on year from 2021 where it was just 71%.

Or looking at how our school provides a stimulating learning environment to our students, which includes questions such as the teachers are very good at making learning engaging and this school provides diverse programs for my child’s interests and abilities indicates that you (our families) think we’re doing a pretty good job.

And we should celebrate this as a community.

But I’m going to do something that many of us in schools do - move beyond what we’re doing well and look for where we can improve. A quick congratulatory pat on the back, and then get back to work. Discover a problem and look for ways to rectify it.

Something we’ve been working on as part of our current strategic plan is developing a sense of agency in our students.

Our current Student voice and agency data looks like this from our parents:

And like this from our students:

So this is where I’m going to shine my torch today. What exactly is agency and why does it matter? What does it look and feel like in the classroom or at home? Why is it that many of our kids feel like they don’t have it?

I’ve attended a number of Professional Learning sessions involving this topic over the last few years and defining student agency is often the first thing asked of us.

This is one definition:

Agency is knowing what to learn, and how to learn and who and with to learn it from to attain expertise in an area of interest

And another:

In the educational context, agency refers to a respectful and more empowered positioning of students to be active agents in their own learning lives. Student agency encompasses both the power of possibility in learning contexts intersecting with the personal desire and will to act.

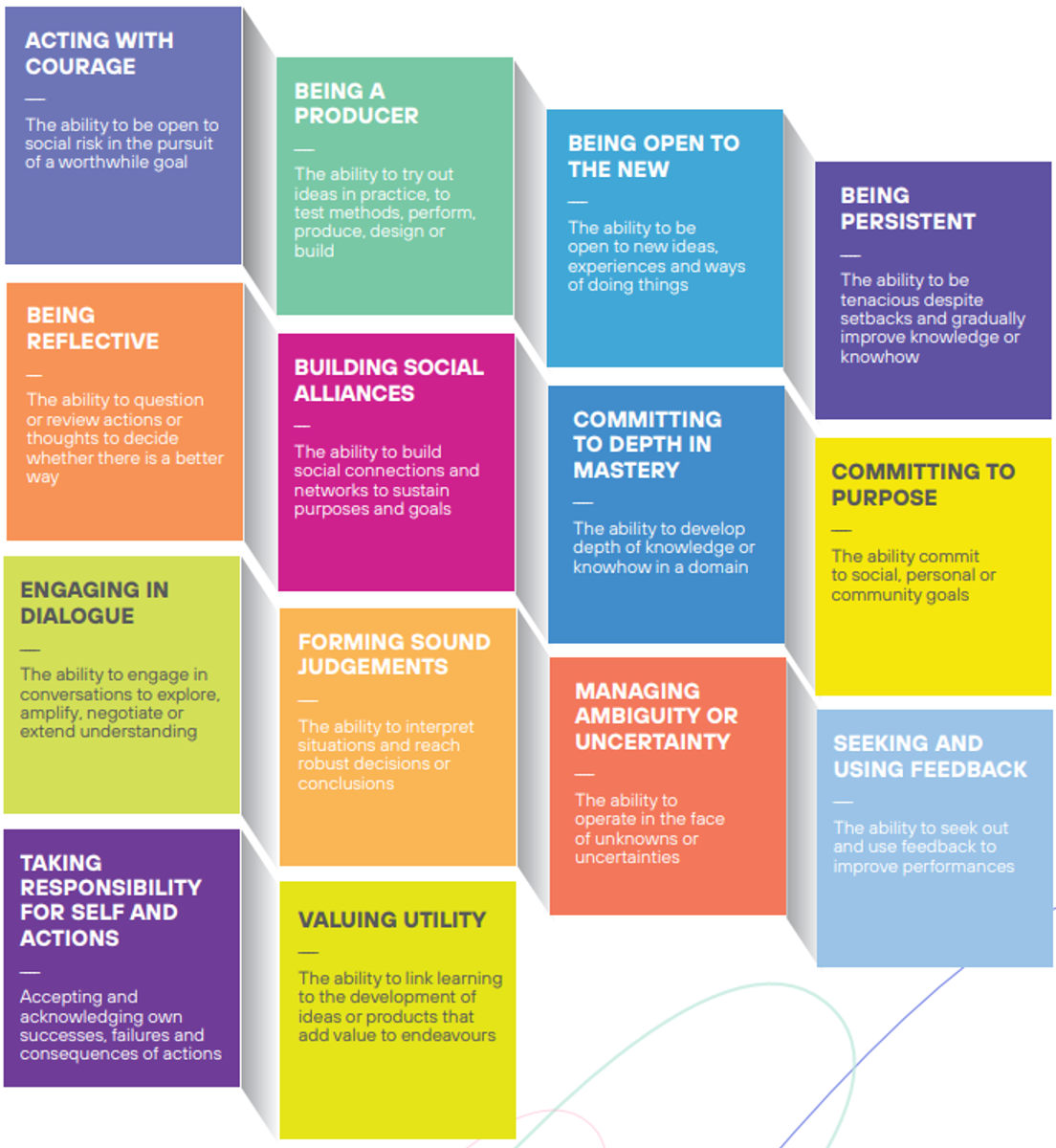

But getting bogged down in definitions is where we can lose some of the excitement of what developing agency in young people can be. So I like to think of agency as building blocks, complex elements that work together to drive deep engagement and understanding. And we, teachers and parents, are always providing our children with the opportunities to work on these skills, often without knowing it!

Why does agency matter?

Research has found that students who have agency in their learning are more motivated, experience greater satisfaction in their learning, and, consequently, are more likely to achieve academic success (Williams, 2017). There is an extensive evidence base that has identified what occurs for students when they have stronger agency in their educational lives:

- They have higher educational attainment and educational success (Buchmann & Steinhoff, 2017; Wigfield, Eccles, Fredricks, Simpkins, Roeser, & Schiefele, 2015; Otis, Grouzet, & Pelletier, 2005; Wang & Eccles, 2011);

- They experience deeper learning and can solve problems they’ve never seen before. (Fullan, Hill, & Roncón-Gallardo, 2017; DET, 2017);

- They experience more personally and socially relevant and rigorous learning when positioned as co-designers who have a role in enacting the curriculum (Shawer, 2010);

- They go beyond engagement to enact real decision making and experience a strong sense of a community, where a willingness to learn together is evident. (DET, 2017);

- Their capabilities and dispositions as successful learners increase – they become more self-motivated, self-directed and deeply engaged learners (Hannon, 2011);

- They work harder, set higher goals, are more likely to choose challenging tasks, are better at planning, have greater focus and more interest, and are less likely to give up (Johnston, 2004);

- They employ metacognitive, motivational and behavioural self-regulation capabilities to make greater learning progress (Siddall, 2016); and are empowered to leverage resources and technologies to make contributions to their learning communities, which include learning materials and ongoing direct feedback where such contributions inform curriculum (Hetherington, 2015).

We feel there is enough research to suggest that this is important work.

In the classroom and at home, we can provide agency through activities where children are applying any of the above skills and dispositions - but unfortunately sometimes using these skills might not feel like they are developing agency for our children. For example, when students are working in a team, they might not be thinking about communicating effectively with their peers as learning, they instead focus on the task that the teacher has asked them to do - this is their learning, completing the task, not all of the other amazing skills they are working on at the same time.

Students often compare agency with choice - that they have agency when they get to choose what to learn, and while this is partly true, it is a shortsighted view of what agency is. Sorry for calling your children shortsighted. But it isn’t just your children that think like this. The four questions that make up that percentage score for student voice and agency on the Attitudes to School Survey include, At this school I help decide things like class activities or rules, I am encouraged to share my ideas, I have a say in the things I learn, and My teacher likes my ideas. And although these questions can provide great feedback for our teachers, they don’t go into what agency actually is, or the skills and ways of being that we are trying to develop at NLPS.

So, this is where David’s voice comes back into my mind - don’t read too much into these surveys. Because we can provide opportunities for our children to develop agency through any of the above building blocks, we can praise them for being persistent and sticking with a task, we can reflect with them, and encourage them to ask questions or use feedback, but when it all boils down to a percentage point on a survey (especially a survey that doesn’t ask what I believe are the right questions), there are bigger, more important things to worry about - like getting to work on developing these agentic little learners.

Maybe David was right.

Mat Williamson

Acting Assistant Principal