Past Pupils' Achievements

Jessica Gardner, 2003

Jess, past pupil 2000 (Year 9) to graduating class of 2003, was drafted in pick 131 to the Western Bulldogs in the NAB AFL Women’s League during the week. She currently plays with the St Kilda Sharks Women's Football Team. Congratulations Jess!

Marcia Griffin nee McIntyre 1963

Why would a Business Woman of the Year be looking for Meaning in Life? What did she find that is worth sharing?

Australians enjoy a high quality of life in a wealthy nation with a strong economy, laidback culture, government-funded education and healthcare, and a stunning natural environment – yet our intake of antidepressants is one of the highest per capita in the world.

This startling statistic is among those that caught the attention of Ms Marcia Griffin who, with Dr Paul McQuillan, has written a new “bookazine” called Finding New Meaning in Life. The unique collaboration between a businesswoman and a Franklian therapist joins the dots between positive self-help and mental fitness.

“We have become a self-centered society,” Dr McQuillan said. “Look at medicine and psychology – it is about ‘cure’, or easing the pain, or becoming a better me, or looking deep inside my past. Human beings can only be better people when they look outside of themselves and give to others. We have all of the means to live, but it seems, nothing to live for,” he said.

“Marcia had the vision because she saw an evidence-based psychological theory to underpin what she had been saying for many years to business owners and others.”

The pair spent three years co-writing the short, practical book, which Dr McQuillan hopes will encourage people to consider an evidence-based alternative to the medical model that pervades therapy in Australia.

A businesswoman and business mentor who has achieved success at the highest levels, Ms Griffin, a former Telstra Business Woman of the Year said she always has been driven to achieve her best in whatever she has set out to do.

“Equally, I have always been passionate about helping others to do their best, to stretch themselves, challenge themselves and get the same sort of satisfaction I have always got from doing my best,” Ms Griffin said. “This book combines my life learnings and business experience – things familiar to all of us – with the psychology of logotherapy. It shows us that having a purpose not only helps us achieve in business, but is good for our mental health,” she said.

“We see our book as a tool that anyone can use to help with their mental fitness and ability to do their best and to have a meaning-filled and exciting life.” Finding New Meaning in Life is a both a self-help book and guide to mental fitness, offering tips and ideas that are accessible to everyone. “It is aimed at everyone who wishes to live life to the fullest,” she said.

Finding New Meaning in Life is available at all good bookstores nationally as well as online at (www.booktopia.com.au)

from August 25. For additional information see https://vimeo.com/167582973

Marcia Griffin nee McIntyre

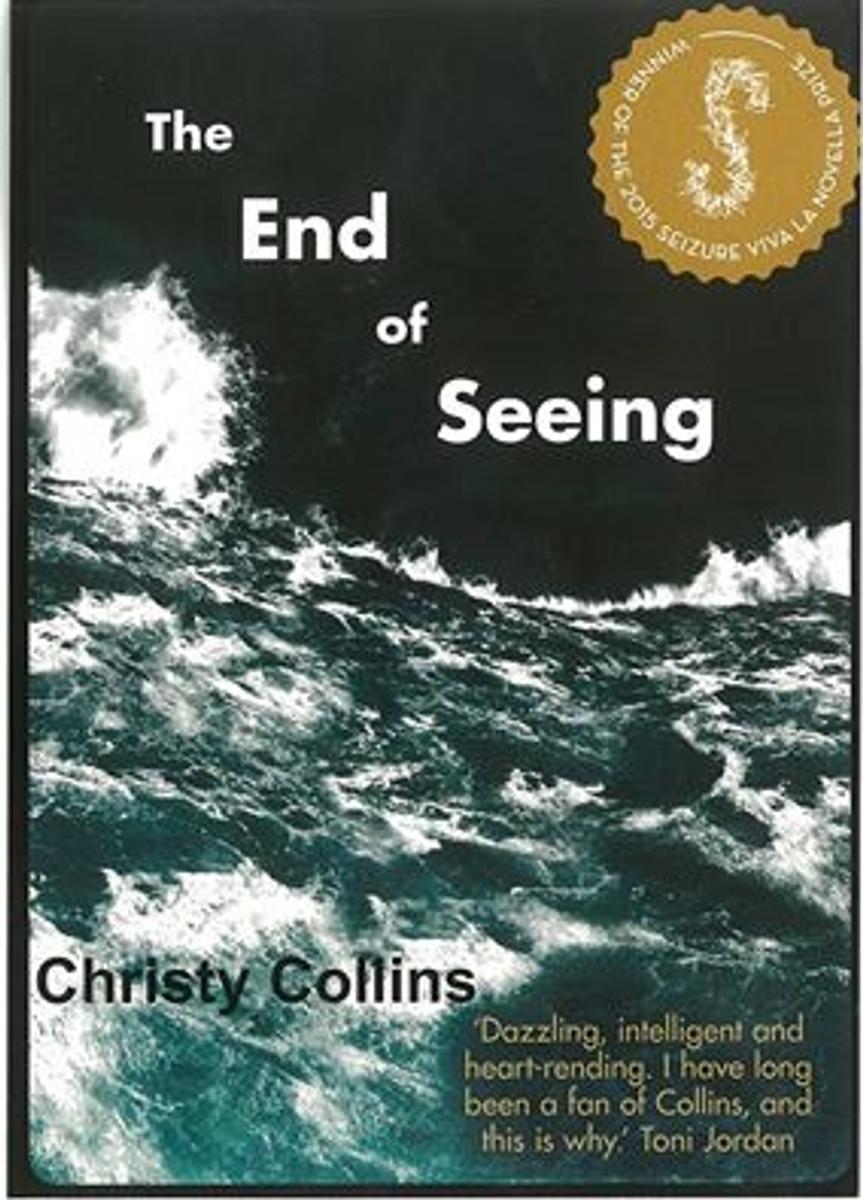

Christy Collins, 1995

Christy is the winner of the 2015 Seizure Viva La Novella Award 2015.

Viva la Novella Winner 2015

Written by Christy Collins

Edited by Nicola Redhouse

Artwork by David Henley

What do you do in your day job/life?

I’m a PhD candidate at the University of Tasmania.

What’s the earliest thing you remember writing?

I remember, before I could read, writing groups of letters on pieces of paper and taking them to Mum and asking: ‘what does this say?’

As far as actual, intelligible writing: I recently dug up a copy of ‘The Inventing of the Homework Machine’ which even has chapters and a laminated cover. According to the bio in the back it is my second book(!) the first being ‘How the Kookaburra got his Laugh.’

When do you like to write?

It changes. I wrote my shortlisted work in the mornings before work, but at the moment I write mostly in the evenings. Generally: when the house is quiet, and there’s minimal chance of being interrupted.

If you could brunch with anyone, who would it be?

Last October, my husband and I walked the Camino de Santiago across Spain. I’d love to have a big, noisy brunch with all the friends we met along the way.

Most important thing the internet has taught you:

That I’m not alone. Writing requires a lot of solitude, but it’s good to be able to connect with other people out there working on their own novels or short stories – and I don’t even have to leave my desk.

A quotation you have used more than once:

‘Writing is like driving at night in the fog. You can only see as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.’ E. L. Doctorow

Life’s a bit like that too.

What’s next?

I’m working on a novel set in the Netherlands in the mid-2000s as part of my PhD studies. It was a strange era with two assassinations that dramatically highlighted the changing face of the country at that time. These events form the backdrop to my story, which is about religion, migration and taking hold of our own lives when the past is complicated for reasons beyond our control.

After you have been gone long enough for me to start believing them, with their soft-spoken story of shipwreck slipping you into the past tense, I go to see a soothsayer living on Collins Street. She says that you are alive and living on microwave meals in Vegas, and I want to believe her so badly that I buy her last copy of The Big Issue for twice the cover price.

I think about the clod of earth I dropped on your empty coffin and the feeling of dirt under my fingernails. I think about my glass bracelet flinging the sunlight across the dirt piled on each side of your grave. I think of the strangeness of Father, we commend our brother Domenic . . . And I think about Vegas and heaven and hell and wonder if some wires got crossed somewhere between the overhead tram lines, the skyscape of fluorescent-lit offices, and a life bundled into a shopping trolley.

You liked Vegas and work kept you going back, a two of hearts taped to your suitcase to help you identify it on the luggage carousel. You liked microwave meals, too. You marvelled at how far we’d evolved and joked about saving the packaging for when the revolution came and plastic would be rarer than diamonds.

Melbourne’s dressed in her own favourite grey. The buildings rise from the rain-blackened streets and office workers slip by leaving pieces of conversation in the air:

‘–said I’d have it to him by Friday and he said Juliana wants it the day after tomorrow, and you know what happened last time–’

‘I thought Paris, but only if the wedding’s in April. But Mum has–’

‘Did you see her hair? Hello, 1987!’

Collins Street’s no place for homelessness or even for standing still.

The soothsayer turns to rummage in her trolley, even though I tell her to keep the change, and though I don’t want to be rude I walk away after a few moments of her incantation: ‘It’s in here somewhere. I know it.’

The café with the good muffins is just around the corner, and I go in and order the pear and almond one before I remember I am alone and can have the raspberry – white chocolate every time now. Silver lining.

I flip open The Big Issue and its centrefold urges me to write to one of the asylum seekers detained at Woomera. For a moment I consider this; I scan the list of names and will one to jump out – my asylum seeker, tracing characters with a stick in the red desert sand: Forgive them Father, they know not what they do.

Then the soothsayer is banging on the window of the coffee shop. I go out with half a muffin in one hand, the magazine folded open in the other.

‘The pear ones are no good,’ she says, and she takes the muffin from me and eats it. ‘I forgot to tell you: you must leave, for the child’s sake – Vegas, that’s over – find a life for the two of you.’

There is no child, as you know. And any plans I’d had for combing Vegas casinos with a photo of you printed a hundred times deflate rapidly as I watch the muffin disappear. Even though I’d told myself this soothsaying thing was all a joke, I feel disappointment rise in my chest. ‘Vegas is over,’ I repeat stupidly.

‘Yes,’ she says, and she looks at me intensely. She points to the page of asylum seekers in the magazine. ‘For him, you hold the key.’

I look where she’s pointing. ‘I don’t–’

‘It’s a new millennium. It’s time to move on.’ And, as if taking her own advice, she begins pushing her trolley up the hill, her head low. People in suits dodge out of her way and I feel sorry; and, being tired of self-pity, I hope it is for her.

I follow and then overtake her, stand in her path and stop the trolley with my hands.

‘You again,’ she says.

‘I don’t think it’s over,’ I say. ‘Not for me, anyway.’

‘Women rarely do,’ she says, ‘but it is, I assure you.’

‘He’s not in Vegas,’ I say, ‘and there is no child.’

‘He is probably where you left him; men don’t move very far on their own steam.’

‘They say he was on a boat to Italy that never arrived.’

‘Italy? It could be Italy. I was always bad at geography. The microwave meals are for sure. Men aren’t good with cooking.’ She reaches down to adjust her sagging stockings. ‘But there is a child,’ she shakes her head, as if trying to get rid of static in the signal, ‘or there was one.’

And, of course, she is right about that. For a moment, when she reaches out to touch my shoulder, it feels like she has known me for a long time.