Humanities

Powerful learning can take place together, even when we are apart

The functionality of Microsoft Teams has worked well for our senior humanities students during remote learning in 2020 and twice now in 2021. Our rich curriculum in the Year 10 elective program allows for collaboration in new and exciting ways. Here are some examples of recent work done in Year 10 Humanities, during Lockdown #4.

Rights Refugees and Radical Regimes

20 June is World Refugee Day, and this year's theme is "Together we heal, learn and shine" - how appropriate! You can see here what different states are doing to celebrate this here: LINK

During our recent period of remote learning, the Year 10 politics elective had the opportunity to collaborate on a Regional Roundup - this is great learning and can only be done by the students having built the foundational knowledge about human rights and geopolitics in our world, together with some explicitly taught critical thinking skills surrounding media literacy. Please feel welcome to take a look at the presentation linked above.

Explosive Decades

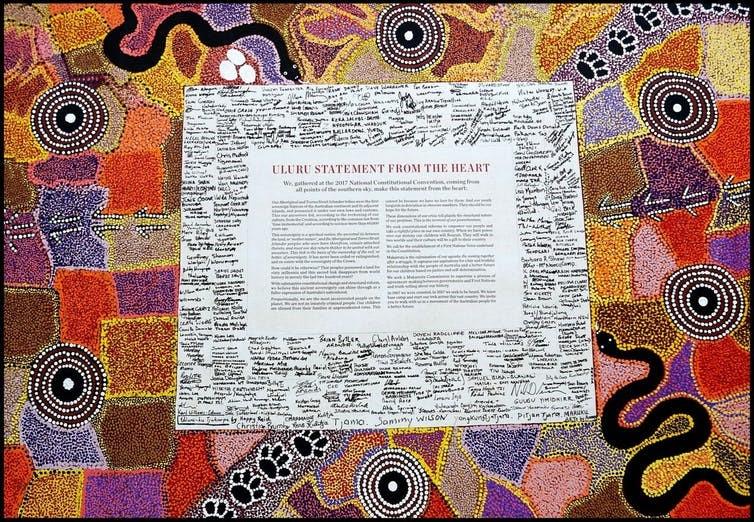

The 1950s-70s were a time of rapid social, political and cultural change in Australia. To round off our study of this era, during remote learning we had the opportunity to dive deeply into the land rights and civil rights movement in Australia, having already explored the corresponding period as experienced in the United States of America.

We learned about the campaigns that built the movement, including the Gurindji Wave Hill Walk-Off, the Freedom Rides led by Charles Perkins, and the campaign for the 1967 Referendum to name a few. We all watched online, spellbound, the reimagined version of Paul Kelly’s “Little Things” by Ziggy Ramo, who performed this powerful song the weekend prior, at the AFL Indigenous Round, in Perth. Using the online collections of the National Museum of Australia, and online historical sources, such as recorded speeches of, for example PM Paul Keating at Redfern, PM Rudd’s Apology, together with the Bringing them Home Report into the Stolen Generations (1997), Report into Deaths in Custody (1991), the Closing the Gap reports, plus the University of Newcastle’s interactive Massacres Map, the students were able to build deep knowledge in a self-paced manner. We were able to connect this knowledge to current events and issues including Black Lives Matter and the Uluru Statement, the first inanimate object to win the Sydney Peace Prize (2021).

Students wrote powerful reflections:

Nineteenth century British settlers met resistance not only physically, but also psychologically. Henry Reynolds explains: “While conflict was ubiquitous in traditional societies territorial conquest was virtually unknown. Alienation of land was not only unthinkable, it was literally impossible… [People] certainly did not believe that their land had suddenly ceased to belong to them and them to their land. The mere presence of Europeans, no matter how threatening, could not uproot certainties so deeply implanted in Aboriginal custom and consciousness. The black owners may have been pushed aside but many refused to accept that they had been dispossessed (Reynolds, 1982, p.65).”

It was not just about fighting but it was also shown through the refusal of Aboriginal people to give up beliefs, the continued will to survive despite dispossession, to maintain connections to land and to culture and communities. However, despite the clear and consistent resistance against the British, history rarely acknowledges it. We are almost never taught about the opposition to the settlers, to make it seem like it never existed. Sometimes terrible historical events are worded in a way to soften and sugar-coat the horrific crimes committed against the Indigenous, very likely because most people in power are the descendants of the oppressors. Nevertheless, it’s important to acknowledge the impressive resistance that the British met.

In Mabo v. Queensland (No. 2) 1992, the High Court found that Australia was not empty (terra nullius) when the first European settlers arrived. Instead, there were already many Indigenous groups living in Australia with their own laws and customs, including laws about land. The Court decided that, where Aboriginal people were still observing their traditional laws and customs and, through those laws and customs, were still connected to their ancestors’ land, then Aboriginal people could claim title to that land.

Nicole Gibson

Teacher of Humanities