Family Zone & Cyber Safety

Download Family Zone

Make use of the Family Zone Accounts which we are offering to John XXIII College families for free, as part of our College contract negotiations until 2020.

By setting up a private Family Zone account, you can apply age-appropriate parental controls on every device your child has access to, in any location. To find out more visit https://www.familyzone.com/johnxxiii-wa

Does your inbox spark joy?

Written by Family Zone Team

To be distracted is to be human. But in today’s digital world, the opportunities for distraction have exploded - while our capacity to deal with them seems to diminish by the day.

In his new book Digital Minimalism, computer scientist Cal Newport proposes a new battleplan in the quest to slay the dragon of digital distraction.

Distraction itself is nothing new. Ever since Homer - whose wily hero Odysseus plugged his ears with beeswax and lashed himself to the mast to resist being lured off-course by the call of the Sirens - human beings have struggled to stay on-task.

But the ancient Greeks had it easy, at least by comparison with our world. With no electricity, and limited reading matter, even the alphabet was regarded as a new-fangled technology (and a potentially disastrous one, in the view of many - Socrates included!).

Social life was conducted face-to-face, as it has been throughout all of human history up to the mid 19th century, with the invention of the wireless telegraph and, later, the telephone.

Samuel F.B. Morse, the inventor of the telegraph and the code named in his honour, sent the world’s first text message in 1844. It read “What Hath God Wrought?” - an appropriate status update for the dawning of the digital age.

Fast forward to fake news, live-streamed human massacres, widespread smartphone addiction, babies who swipe before they can crawl, data mining and identity theft, primary school kids watching porn and a worldwide obsession with “likes” and “followers.” Now more than ever, Morse’s question reverberates with renewed relevance. But enough with the questions, already. How about some answers?

Subtitled “Choosing life in a noisy world,” Newport’s book Digital Minimalism makes the case for a philosophy of technology use that revolves around the deceptively complex notion of “enough.” (And yes, he has been called the Marie Kondo of the digital world.)

Practical tips like turning off notifications, putting your phone on “Do Not Disturb” while you sleep or indulging in the occasional, short-lived digital detox are all well and good. But what we really need is an entirely new relationship with our technology - one that puts at the centre a state of mind he calls “Deep Work” (and you and I might simply call “concentrating on one thing at a time”).

Newport defines Deep Work as “the activity of focusing without distraction on a cognitively demanding task … when you’re really locked into doing something hard with your mind.”

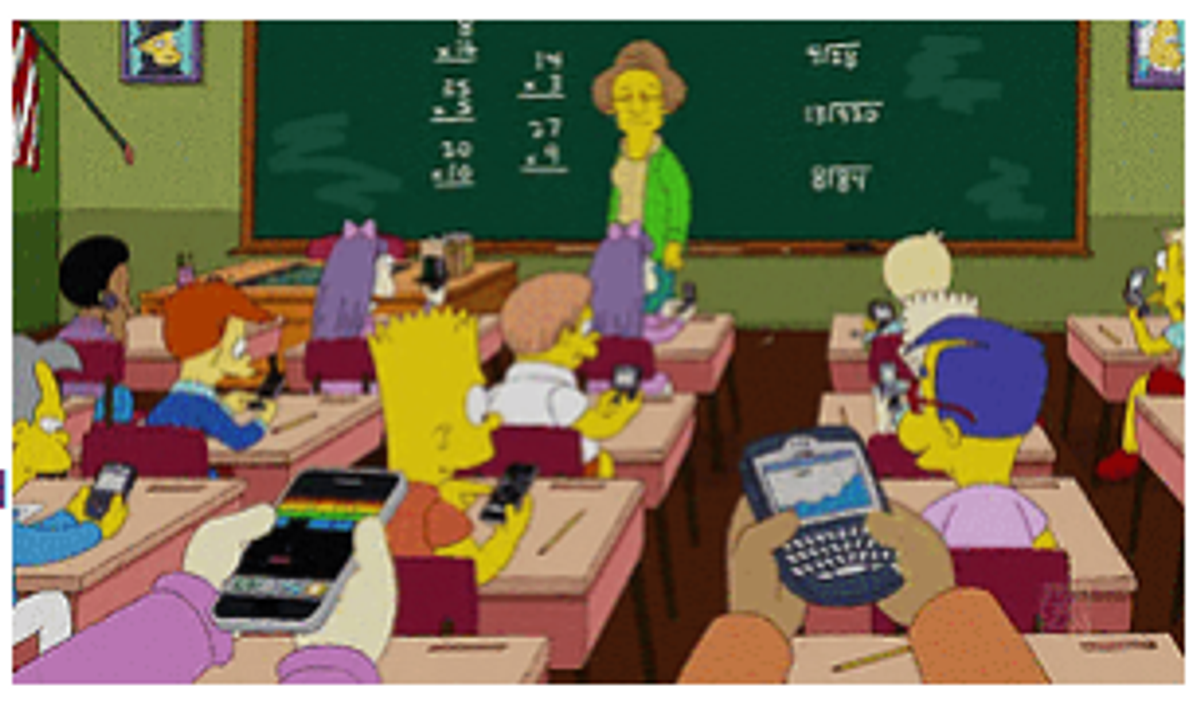

Recent research has shown that even a quick glance at a notification or update can significantly reduce performance on such tasks. (Writing blog posts very much included, in case you were wondering.)

“Every time you switch your attention from one target to another and then back again, there’s a cost,” Newport explains. “This switching creates an effect that psychologists call attention residue, which can reduce your cognitive capacity for a non-trivial amount of time before it clears.

“If you constantly make ‘quick checks’ of various devices and inboxes, you essentially keep yourself in a state of persistent attention residue, which is a terrible idea if you’re someone who uses your brain to make a living." The implications for teaching and learning in today's digital classrooms are obvious - and dire.

Among Newport’s other pillars of digital minimalism, he advises:

Embrace boredom - If you always whip your phone out the second boredom rears its unattractive head, your brain, he says, will inevitably connect boredom with the need for instant stimulation. And that means when it’s time to think deeply - a task that’s usually deficient in moment-to-moment novelty - your brain will rebel.

Quit social media - It’s not as hard as it looks, Newport insists. (He’s never had a social media account of any kind himself, so it’s not entirely clear how he knows that.) Otherwise, you risk “a digital life that’s so cluttered with thrumming, shiny knots of distraction pulling at our attention and manipulating our moods that we end up a shell of our potential.”

Drain the shallows - “Shallow work” is Newport’s term for digital admin stuff - emails, most notoriously - that can suck up the time we would otherwise spend working deeply. He advises aspiring digital minimalists to aggressively reduce the time spent on such tasks, to make room for what really matters in work and … that other thing.

What do you call it again? Oh yeah. Life.