English News

PESA

On the third Thursday of the month, representatives of Nossal High School attended the 2022 state semi-finals of the yearly Plain English Speaking Competition. PESA is an event in which Nossal has been successful on multiple occasions, as numerous students have progressed to the state level in the last ten years, with one even coming runner-up in Victoria. There were many wonderful prepared speeches given, but the highlight of the event was undoubtedly our own Mila Vargas' startling exposé on the monolingual mindset and its prevalence in contemporary Australian society. This round of oratory was followed by further impromptu speeches in which once again Vargas surged from triumph to triumph, responding in a vivid and achingly evocative manner to the prompt 'The Weakest Link' by calling on our common humanity and expounding on the importance of deconstructing negative stereotypes. In an entirely justified ruling, the adjudicators placed Vargas first in her heat, winning her a badge and the chance to compete at the state level.

Many thanks to Ms. Natalie Faulkner, the member of staff affiliated with PESA at Nossal, for her attendance and relentless championship of the program over the school year. The English department in particular has been instrumental in facilitating this growth of our public speaking community by encouraging students in DAV debating and even hosting the early stages of PESA for our district. We wish the best of luck to Vargas in the coming levels of the competition and any public speaking endeavours in her future.

Lola Sargasso

Year 12

Creative Writing

Casey Fresh Words

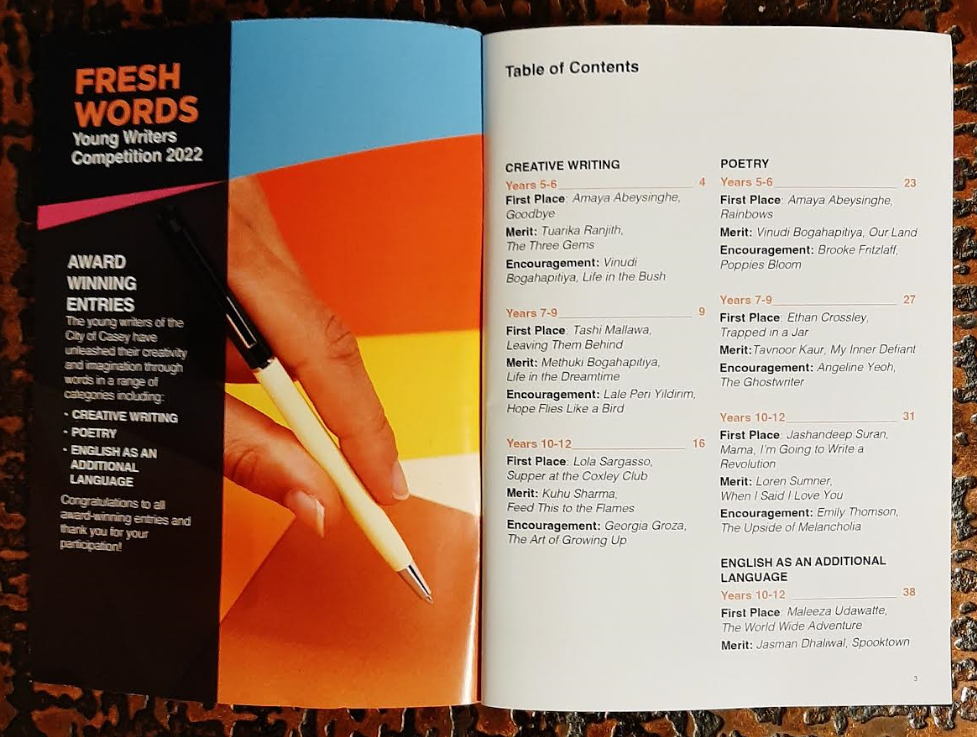

The City of Casey Fresh Words Writing Competition is a free annual writing competition open to all students from Year 5 to Year 12 who live, work, or study in the City of Casey. Students are open to submitting no more than two pieces of their work from a range of creative writing, poetry and lyrics, or English as an additional language – the work will be judged according to the Junior (Grade 5 and 6), Intermediate (Year 7 to 9), or Senior (Year 10 to 12) age categories.

The finalists and winners of the writing competition proceed to attend an award ceremony. This year’s award ceremony was held on the 22th of June. George Ivanoff was the guest speaker and imbued a sense of passion and ‘fun’ (as so he calls it!) into everyone as he celebrated all award winners. It was an amazingly fun time and it can probably be guaranteed that everyone was ecstatic to meet other young writers with every ability and capacity to change the world with their voice and written expression.

Supper at the Coxley Club

We bucked the morbid hold of the darkness and stepped inside. It had been a grim, fetid day, the warmth of the summer to come leaking over in a dull rush, and as I walked into the Coxley Club for the first time I was stunned by its pure luminescence. Chandeliers dripping moonbeams hung from elaborate hooks on the domed ceiling, and everywhere you looked shafts of light hit gilt and fragmented into a million heady filaments. My eyes watered.

We were out celebrating a birthday, or a marriage, or perhaps a tricky case come to an easy conclusion. My colleagues bore down on a side table, evidently reserved either for our firm or our party, and I shook off the starlight and made to join them.

A gentle hand held me firmly back.

He was a young man, tall and dark with a pronounced stoop to his shoulders that belied his age. I passed him my overcoat, still slick with spring rain, and he handed me a tulip pink check slip with a gilded border. Our fingers met. Business concluded and released from him, I slipped into the corner of the booth.

The menu was, I think, a surprise. Certainly I found myself at a loss, and sat there fading while the effervescence of my colleagues soaked the building. They laughed, and the Coxley Club was a reflection of their laughter. We waited for a time, spent in chuckles and chatter and complaints about upper management, and then the first course came. My hunched waiter helped to serve. I found myself looking at his hands, the coarse red lines drawn on his palms that spoke to long nights and hot water. He left, and I was left with the meal.

I had not thought that I could eat unicorn, but in truth it was easy. Barely a mouthful of it had passed through my lips before my mind was eased and I began chatting to the fellow on my right as if it were nothing strange. This was, he told me in between forkfuls of shank, the great joy and privilege of the Coxley Club: good company, fluid conversation and, what he considered to be of ultimate importance, a damned pleasant supper. I nodded my agreement.

The meals kept coming, on gilded plates and china saucers and silver platters. My party applauded at the entrance of stuffed phoenix's breast, and its successor, a rather piquant sautéed mermaid's tail, was greeted by paroxysms of mirth and good humour. I was happier than most and hungrier than all, held rapt like a dying man at a last minute reprieve.

The last dish, we were told, was something truly special. Unheard of in polite society and procured at vast expense, the angel's wing was an unparalleled delicacy and one that was only to be had at the Coxley Club. The plates were handed out, and, as he laid mine down on the varnished table, I noticed my stooping waiter's hands were shaking. Drunk on champagne and atmosphere I cheered with the rest of them, then sat, then began my meal.

There was nothing in the taste of that angel's wing. Nothing but an emptiness, a vast and terrible absence that made me suddenly frightened. The sounds of the Coxley Club grew to fever pitch. Nothing else had changed. The men around me rhapsodised through open mouths, grinned widely, picked at their teeth with bone. Slowly, I took in another mouthful, savouring the ash.

I met him again at the coat check, clutching the ticket to my chest like a precious thing. He stepped softly into the back room and I wondered how he had learnt to walk without his wings, their constant crushing weight. Still pregnant with rainwater, my coat dripped starlight on the marble floors. I looked up at him as he handed me my coat. I looked into the eyes of the angel and for an instant, one shining instant, I saw that glory that is untold and unspoken of in human tongues. Ecstasy, sorrow and above all a strange and bewildering pity were mingled in his gaze. I could have stayed there forever, withering into mould and dust under his eyes, but the rough nudge of a souse knocked me aside and by the time I looked back he was lost in a whirl of suit jackets. The drunken man took my arm in his, and together we made our way into the night.

Lola Sargasso

Winner of the Y10-12 Prose Category

Year 12

Mama, I’m Going to Write a Revolution

In the land of five rivers, the majestic land of eternal kingdoms,

My mother wore a veil over her head

And marched to the Delhi border

Unafraid.

In the land of ancient civilisations and wondrous mythology,

My mother spent cold winter nights awake

Calculating food portions for the next day

Until the winter solstice would lull her to sleep

In pity.

In the land of folklore and yellow mustard fields,

My mother made me her little farmer

And handed me a pen and wax paper

I looked up to her and I gave the paper life.

In the land of folk dances and gurudwaras encrusted in gold,

My mother wore a veil over her head

And marched to the Delhi border

Unafraid.

But the authorities only boasted their power,

With tanks and machines.

In the midst of the numbing winter,

They called my mother a ‘feminazi.’

I was furious, I was choking back tears, I was humiliated because

If they associated my mother with them, they associated me with a group I never intended to be

And I can guarantee, Mama,

It silenced me

But it did not censor the rage simmering in my soul

The paper you once gave me, I turned it into a scroll

Of emotive poetry and raw prose

Mama, listen! Do you think I’m a good farmer?

Look, I’ve even adorned myself with your armour.

You wait, mother, can you hear me yell your name?

I wish you could see this; it’s humorous, look at the audience I will inevitably tame.

Jashandeep Suran

Winner of the Y10-12 Poetry Category

Year 11

Feed this to the flames

Keratithe was a girl with a name. She was young, and she was a little sweet, a little sour. She carried a bag of Grief with her. I still remember, the languid whorls of aching sadness in her atriums and ventricles. I can feel them now. Like rich, caramel sauce. She carried cotton candy lightness with her too though. She was soft like clouds. It was because she believed. Not in anything, but in belief itself. In her good moments, she would reach out and touch the magic that formed the world and feel a little better.

However, she had long since been battered by The Wind. Again and again, that might rushed up against her. Again and again, she built and wielded magnificent weapons to fight with The Wind. She would not give up. Again and again, The Wind blew them away from her hands.

Although she tried to hold firm indeed, the state of her soul was quite blatant at times. And though people didn’t understand, they at times did see that gap between what-was and what-should-be. So, she was told, Keratithe, you are not the same as us. Keratithe, there is something you miss. You lack something. Though she heard these words and listened to them and felt them – she refused to believe them. Keratithe was a proud creature. She was going to show them. She would not fall, not she. Keratithe was not weak as they taught her, she was a warrior who battled with The Wind.

Nevertheless, it was true that she was at the edge of a cliff. Suddenly, The Wind came again with shocking force. It knocked the midnight-haired girl down, and she got to her feet quickly, calling forth her trusty sword, Angerr. She thrusted and parried, side-stepped and leaped. She survived, and there was a moment of respite. Yet The Wind came again, and this time, it had grown in power. It was a many-headed, relentless beast. Angerr was knocked from Keratithe’s hand, and it fell into the Abyss. She stood peering into it, right there on that cliff.

Keratithe was next to go. Down she fell, buffeted by The Wind. Torment, pitch black and pervasive, was spread throughout the Abyss. Blocking the warrior girl from her sword, Torment whispered with The Wind, and the girl wept. But there was another creature, lurking in the Abyss. This creature opened one eye lazily and whispered answers into the girl’s ears. Yes. Keratithe would go on by any means. She would survive again. Exhausted, and silent as the moon, she exhaled her Being. Out, into the air it flowed, shimmering even in the darkness. A myriad of untold colours.

“Feed this to the flames”, whispered Keratithe.

Fire was called and lit. The Being, her very essence, was thrown into the flames, and the creature, that had so slowly opened her eye? She jumped after it. Keratithe waited and faded. Her Being had been swallowed whole, burnt to ashes. However, on many accounts, this narrative was false. For she had not lost; she had fought. She had not wilted; she had grown. She was lost, that was true. In her wanderings, she had stumbled upon the Well of Words. Here she spent most of her time, considered death by drowning and rejected it. She found other artifacts that had been thrown down there, long-forgotten and dusty, and she kept them for company. The Torment could come and go, but she was here to stay.

However, her time in the abyss really was terrible. I remember, I do remember, that bittered honeycomb residue it left in her soul. Still, it was only a little. There was plenty else to enjoy.

Keratithe, one day, had had enough. No more would she walk, filling herself with emptiness, sagging from the void in her stomach, blinking from the Miserie paint on her eyes. No. It was not that she never fell. It was that she always stood up. It wasn’t for them; it was for her. Proud creatures did not fall. The ever-walking-the-winding-road girl had made up her mind. She knew what to do.

All that could not be fought, must be faced. She had to name the demon. The creature who had fed this to the flames. Though there is more to her than I earlier told you. The creature who, with dripping disdain, opened her second eye. The creature who fell into the flames fearless. The monster that ate her. For it was I.

“Keratithe.”

Kuhu Sharma

Merit for the Y10-12 Prose Category

Year 11