Teaching & Learning Page:

Web Pages:

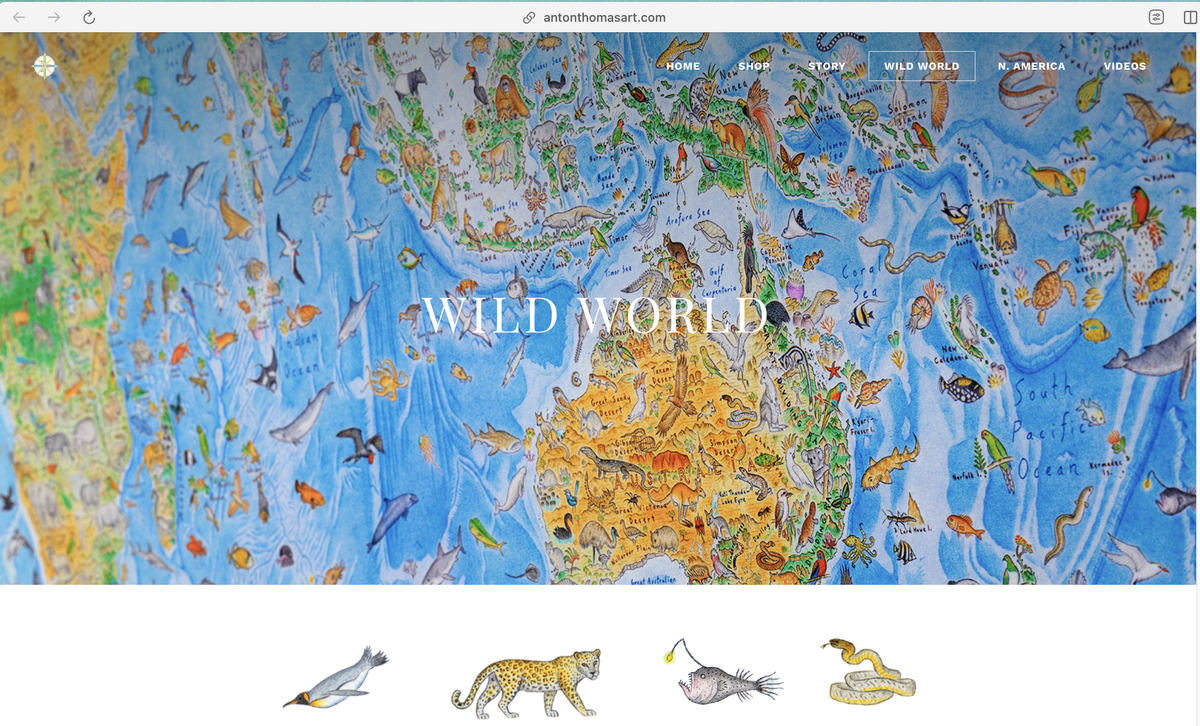

https://www.antonthomasart.com/wild-world.html?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

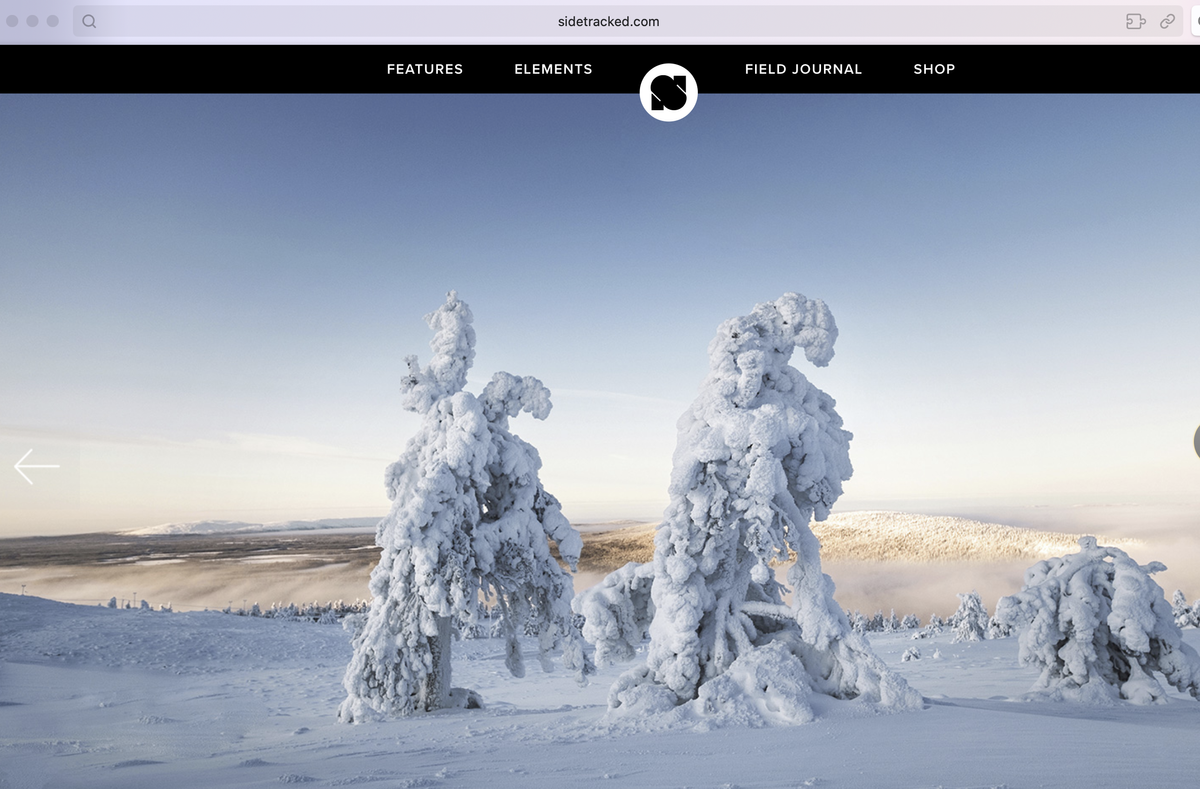

https://www.sidetracked.com/myths-of-the-north/

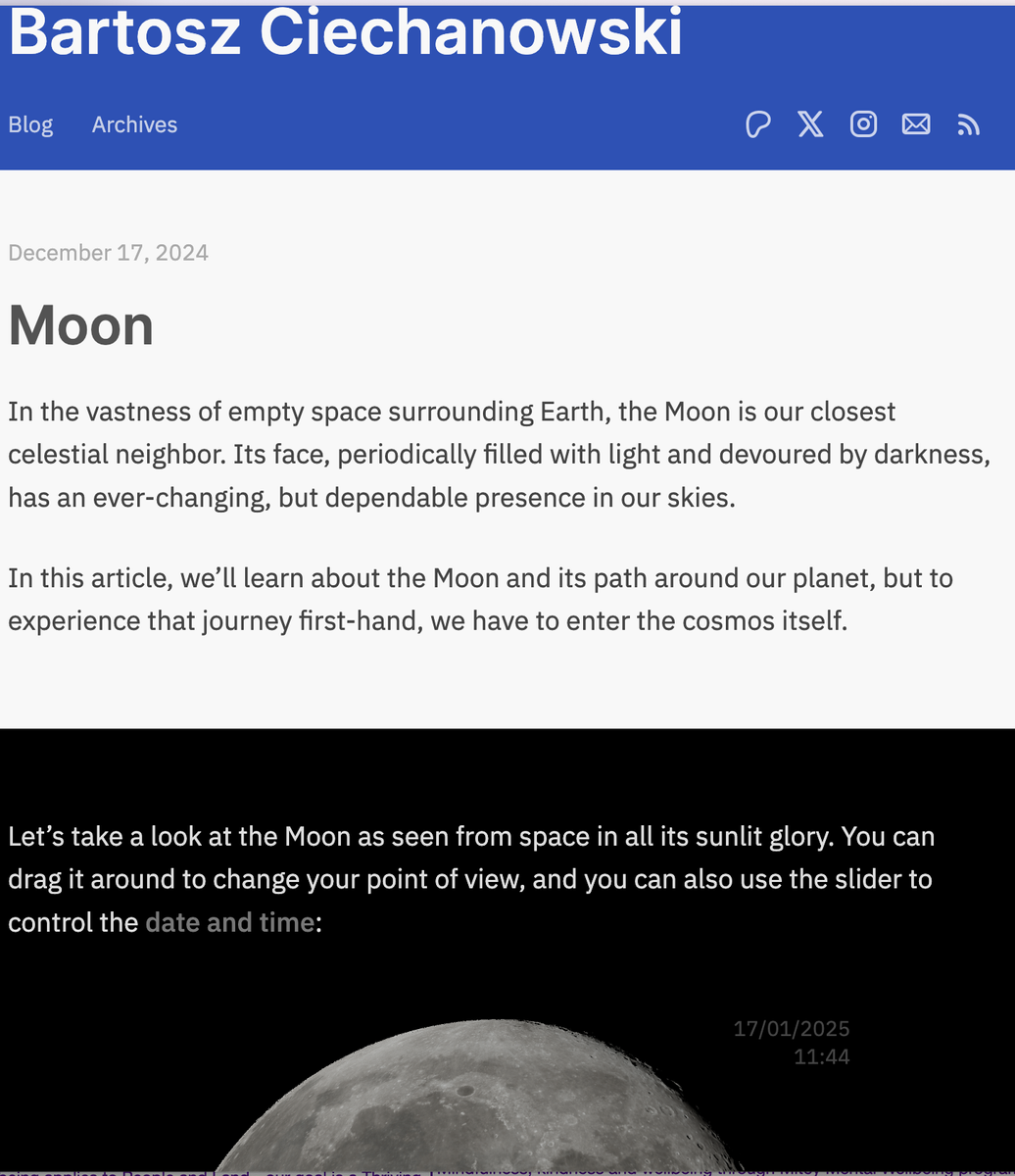

https://ciechanow.ski/moon/?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

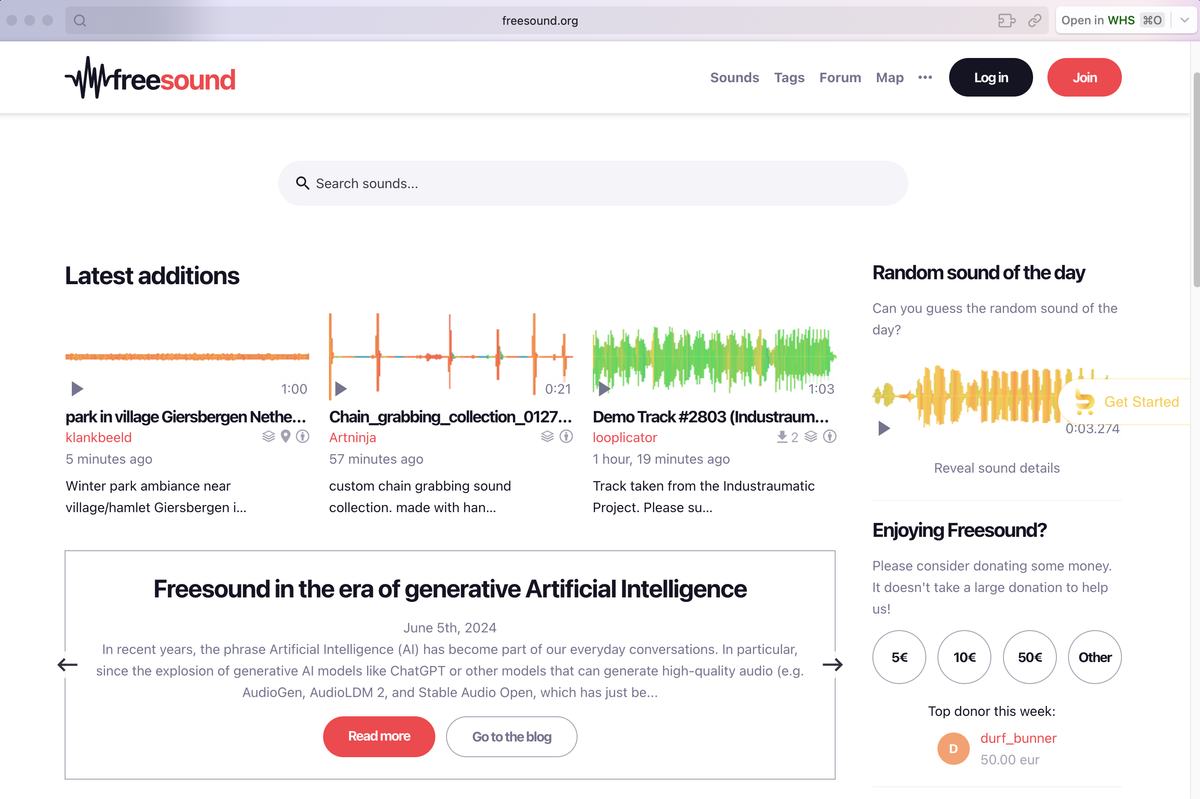

https://freesound.org/?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

Techie Tips:

We all know that double-tapping on a word while writing highlights it, but you can also tap to select the entire sentence or a paragraph.

To do this, you triple-tap on a word of the paragraph you want to highlight. Triple-tapping on a word will select the entire paragraph instead of selecting a word. Also, this will save you time without dragging the selection borders to highlight a paragraph manually.

Shaking your phone to undo is an easy, if unusual, gesture. For example, you could swipe left using three fingers to undo the text. Similarly, swiping right with three fingers will redo the text.

Sketchplanations - Spot the Common Theme...:

Why is the save icon in your software a floppy disk that no one has used for over 20 years? And that phone icon looks nothing like your mobile phone when making a call. These are both skeuomorphs.

What is a skeuomorph?

A skeuomorph is when a new design borrows practical elements from a former design and repurposes them in a functional or ornamental way.

Skeuomorphs are practical in that they make new systems more intuitive. They can help bridge old and new ways through their comfort and familiarity, such as air intake vents in electric cars that make them look like traditional combustion cars.

More poetically, a skeuomorph can offset the loss of physical reality when interacting with our digital devices.

Skeumorph examples

Skeuomorphs abound in the digital world:

The save icon is a floppy disk from the 1980s and '90s.

Microphone and speaker icons.

The bin icon for deleting files.

The battery icon on your computer.

The envelope icon for email.

Gears for Settings.

Storing files in folders.

Books apps displayed with bookshelves.

The magnifying glass to zoom.

The camera icon as a physical SLR camera.

The shopping cart in an online shopping site.

The 'desktop'Sliders and knobs, or even connecting wires, are made to look like analogue mixing desks and gear in music software (music software is awash with skeuomorphs)

A link icon is represented by a link of a physical chain.

A clipboard for paste.

Dials and levers or a funnel representing filters.

Shadows under boxes on a webpage simulate light falling on a surface to show depth.

Grab bars are indications of friction points where you can change the order of a list.

The list goes on and on.

I once read that when designing, if you can't think of an icon for your feature in about five seconds, you should probably write the word, as not everyone will understand it.

Not all digital icons are skeuomorphs: the printer as the print icon and the folded page for a page layout still map to their physical counterparts.

Physical skeuomorph examples include:

Electric candles.

Slot machine levers that change the state of a circuit rather than spin any wheels.

Fake wood grain is used on floors or interiors.

Haptic feedback—a simulated click when pressing on a touchscreen .

Speed camera signs in the UK use a stylised visual of a classic Kodak Brownie camera. Rivets on jeans are from when fixing denim together required more than just stitching. Electric cars sometimes include imitation air vents at the front that cool traditional combustion engines.

Car hub caps with spoke designs from early wheels.

Textured wallpaper, such as Anaglypta, echoes leather wall hangings with scored patterns.

There's even a design for an early car with a fake horse head on the front—though the inventor designed it to avoid scaring other horses on the road.

A smartwatch isn't just a watch; it's a computer you wear on your wrist .

Skeuomorphs can borrow sound also:

The imitation shutter sound of taking a photo on your phone.

Simulated engine noise on an electric car.

Skeumorphs in Software and User Interfaces

Software and the digital domain are ripe places for spotting skeuomorphs, as they lack physical characteristics—they are all 1s and 0s that we can't see or interact with.

Apple's early iPhone interfaces were famous for their skeuomorphic elements, such as a Contacts app that resembled a contacts book complete with tabs—tabs are also skeuomorphic—and fake leather or paper effects in note apps.

Skeuomorphs, like metaphors in design, are helpful. In a magic box that can do anything—a mobile phone—a visual connection to a physical object with a defined purpose helps immediately tell you what something might be or do.

As the digital world gradually becomes the first interaction for so many uses, skeuomorphs may become less common. But we'll still see them around for decades.

Early skeuomorphs

Skeuomorph is not a recent term. Archaeologist Henry Colley March coined it by combining the Greek words skeuos (σκεῦος), meaning container or tool, and morphe (μορφή), meaning shape.

Skeuomorphs have been used in art and architecture since ancient times. They are decorative features of stone buildings that mimic structural elements from older wooden ones, such as protruding rafters. Ancient pottery sometimes includes decorative rope patterns on the surface.

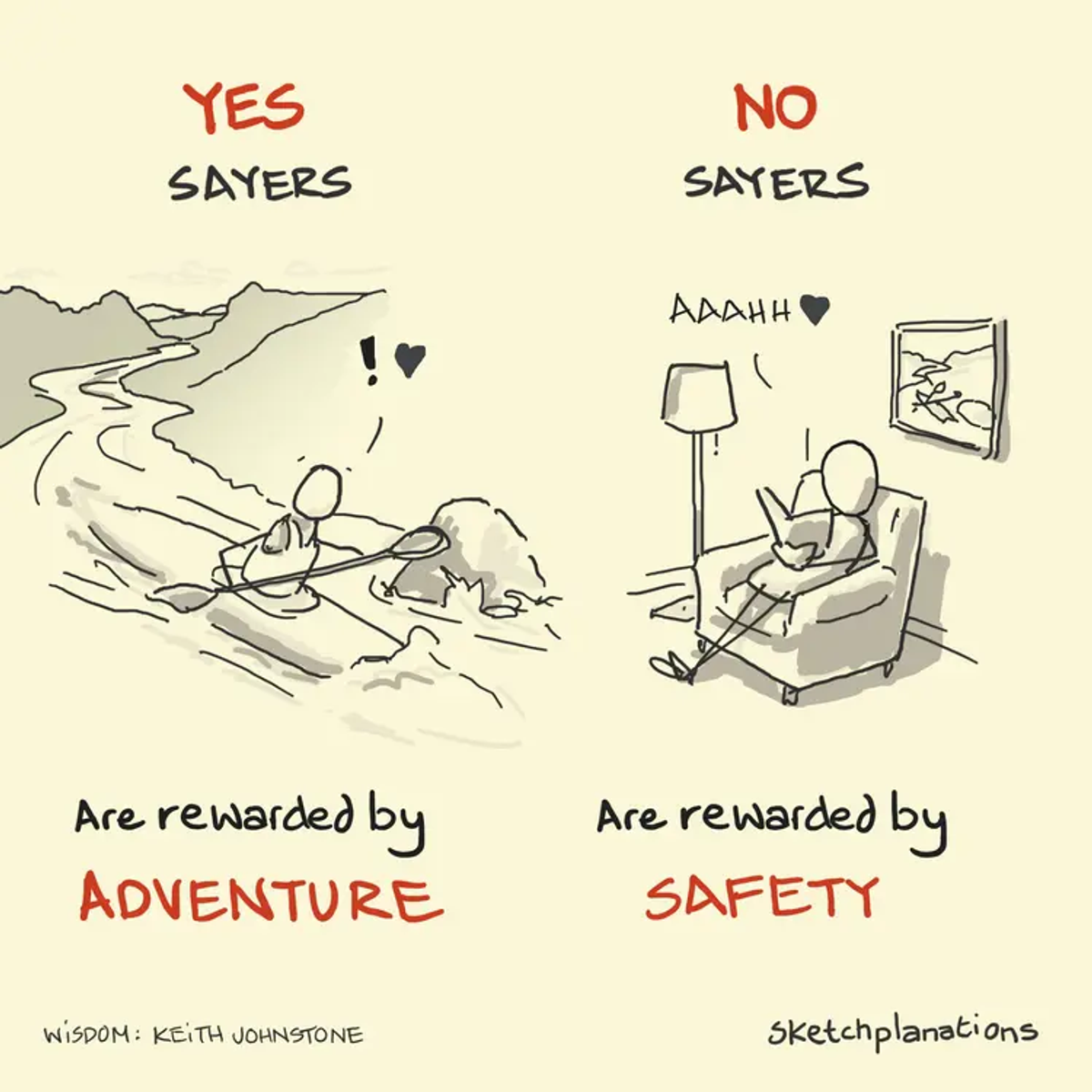

Improv veteran Keith Johnstone shares:

There are people who prefer to say "Yes," and there are people who prefer to say "No." Those who say "Yes" are rewarded by the adventures they have, and those who say "No" are rewarded by the safety they attain. There are far more "No" sayers around than "Yes" sayers, but you can train one type to behave like the other.

I can't help but put pressure on myself to be a yes-sayer. Perhaps it's the vague belief that saying yes will lead to a fuller life and range of experiences and that saying "no" is the easy option. And somehow, the easy option in my mind can seem like the wrong option. That's why I liked Keith Johnstone's framing for yes-sayers and no-sayers, as it clearly shows the rewards for taking either route in a decision, not just one.

If you are improvising, saying yes and accepting offers takes you to situations that may not feel comfortable but give you new experiences.

Saying no keeps you where you are. Your situation is known and safe, and you feel good about it.

In life, we never have to be exclusively yes or exclusively no. And it doesn't have to be white-water kayaking for yes-sayers and reading books at home for no-sayers. But certainly, there are different joys in each path. I love both: the nerves and excitement of new experiences and the comfort and safety of the known and predictable. We needn't bucket ourselves into one or the other.

An adventure, even a micro-adventure, is almost by definition the result of saying yes. Like Type II fun, it can be rewarding and fulfilling. But balancing adventure with the safety and calm of staying in one's comfort zone sometimes feels nice to me.

Article:

How to Plan Better

What’s Planning in Reverse?

Planning in reverse basically means pausing to plan your tasks after you’ve already

started working.

For many people, planning ahead often backfires for three main reasons:

- You don’t know what you don’t know. Sometimes, you won’t know what you need to do when learning something new, making it impossible to plan ahead.

- Plans often change. It can be frustrating to spend lots of time planning the tasks you think you’ll end up working on, only for things to get disrupted.

- Designing your plans can take a long time. Decorating your planner is a rewarding creative exercise that can motivate you — but it’s also time-consuming and not always practical.

Why Planning in Reverse Works

Lets you jump straight into a project and start practising new skills.

Reduces the time it takes between a new task popping up in your brain and you

starting to work on it.

Helps you identify roadblocks and figure out how to solve them.

Gives you clarity on how much of the work you’ve already done.

How to Plan in Reverse

Step 1: Start working on a task or project

"Just start” isn’t always helpful advice, but it is the first step.

That said, some level of planning ahead might be involved here, especially for people

who are neurodivergent. You might need to set reminders, practice boundaries, or do

what works for you before you can start.

Step 2: Work until you get stuck or overwhelmed

Once you’re stuck in, focus your full attention on your task. Your goal for this step is to

get into a “flow” state, if possible.

Also, don’t forget to take plenty of breaks — at least once every 2 hours — to keep your

brain in top form.

Step 3: Pause and plan in reverse

If you hit a roadblock or you’re feeling so overwhelmed that it’s distracting

you from getting things done — it’s time to plan in reverse.

You’ve already done a chunk of the work, so pause to check in with yourself:

Dump out some (or all) of the tasks you’ve already done and tick them off, if it helps.

List all the tasks you still need to do.

Indicate which tasks you’re having trouble with and why (it’s okay if you’re not sure).

List your top goals and priorities for the work you’re doing. From here, work

backwards to uncover which tasks require your immediate attention and which can get moved to the back-burner.

Review your top tasks and consider the types of obstacles you may or already have

encountered. Jot down some ways to work around the most urgent ones.

Listen to your feelings. Emotions can get in the way of work, so take a moment to

process and address them, if needed.

While you can do some of this in your head, you might need to do some light journaling

here to get the answers you need.

Step 4: Pick a small task and start working

Now that you’ve got your list and you’re feeling calmer pick something small and get

back to work. (Or, take a break before coming back.)

It can be hard to jump right back in after feeling stuck, overwhelmed, or defeated —

that’s why we recommend starting small and slow.

But if going slow doesn’t tend to work for you, set a timer and “race yourself” to see how

much progress you can make in the allotted time.

Book Recommendation:

Never Enough: From Barista to Billionaire

by Andrew Wilkinson

Okay, imagine that you love chopping wood in your backyard,” I said. “You do it for fun. To relax. To enter a flow state.

Then, one day, your neighbour pops his head over the fence and asks you if you could chop him some wood, too. He offers you $20.

Suddenly, the thing you love doing becomes a business. Before you know it, you’re chopping wood for all your neighbours.

You buy a truck and start selling door-to-door. It’s just you and a bunch of buddies, side by side, chopping wood and working outside.

The business grows. And grows. And grows. And a decade later, you wake up. You’re in a little glass office perched atop one of many sawmills. You look down at the hundreds of workers beneath you, operating the industrial equipment on the factory floor. Huge logs getting fed into machines that slice the wood. Totally automated. “And there you are. Isolated in your little office, wearing a suit, the air-conditioning blowing a chill down your back. No axe. No fresh air. No friendly coworkers. Just you sitting in your office, doing some paperwork- alone.

That is what it feels like to build a business this big.” He looked dejected, and I wondered if I should have just shut my mouth and told him it was awesome. He could learn the truth on his own. Every founder dreams about getting to the end - the part where they’ve created the billion-dollar behemoth - but ironically, once there, we all fantasize about going back to the beginning. After all, the beginning is the best part, and most of us probably wouldn’t have kept going if we knew about all the speed bumps. The journey is the reward.