Teaching & Learning Page:

Web Pages:

https://www.fbi.gov/history/artifacts

httpswww.fieggen.comshoelaceindex.htm

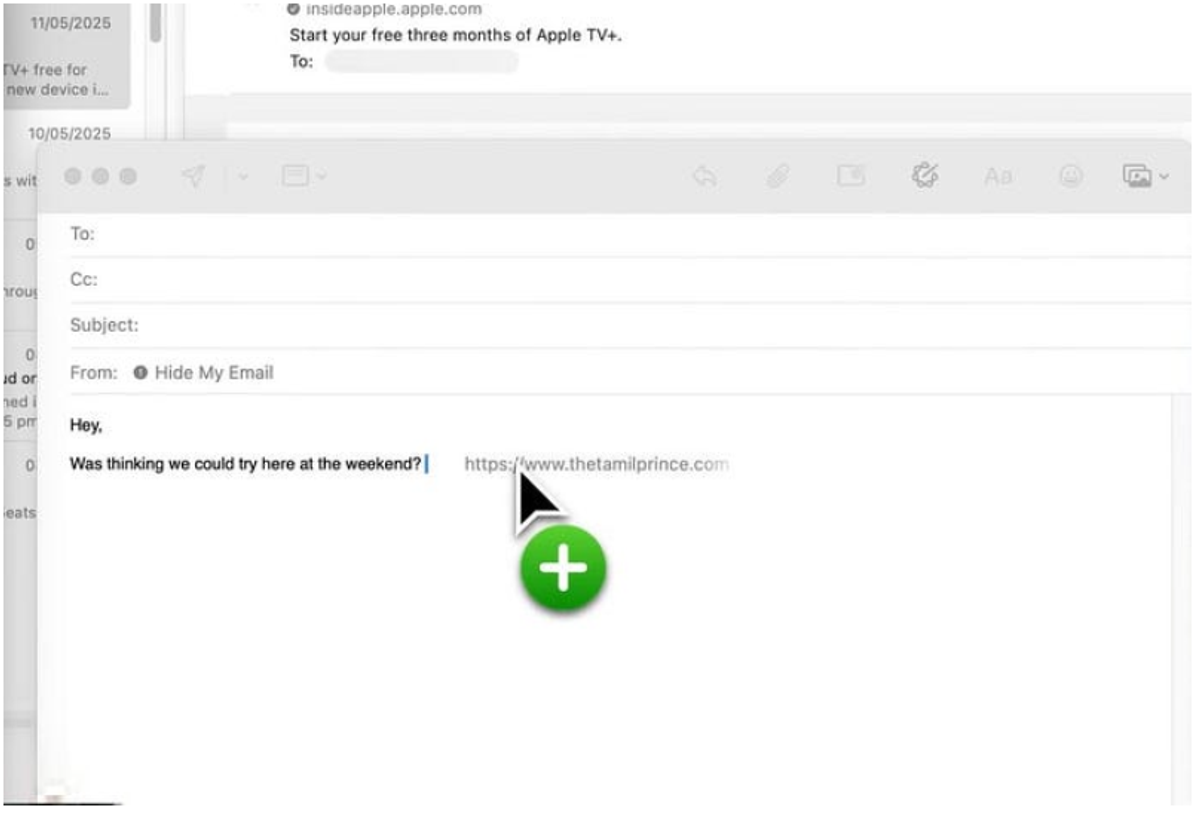

Techie Tips:

Drag URLs Straight into Emails

No need to copy-paste URLs from Safari. Just click and drag the address bar, or even a link on a webpage , straight into your email or note. It is quick, intuitive, and more elegant than a copy-paste.

Rearranging (or Removing) Menu Bar Icons

If you want to tidy up your top-right menu bar. Just hold Command and drag icons left or right to rearrange them. You can even drag them down off the bar to remove them completely. If you want.

Don’t worry, the apps stay, just the icons go.

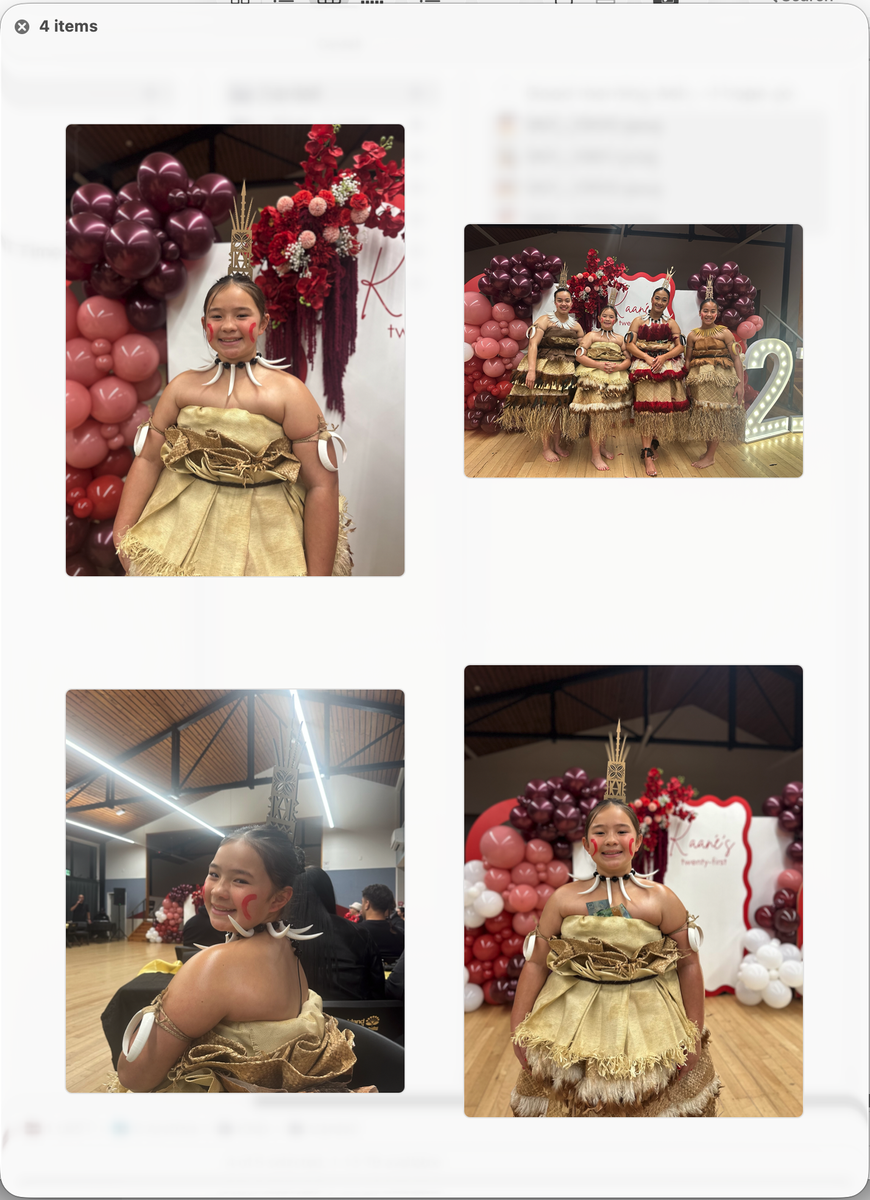

Instantly Preview ALL Photos using Quick Look

Select all the photos you want to preview and press the Spacebar to open Quick Look. Then, hit ⌘ Command + Return to switch to grid view, where the selected images appear all at once. To exit grid view, press ⌘ Command + Return again. You can use the arrow keys to browse through the images.

Sketches:

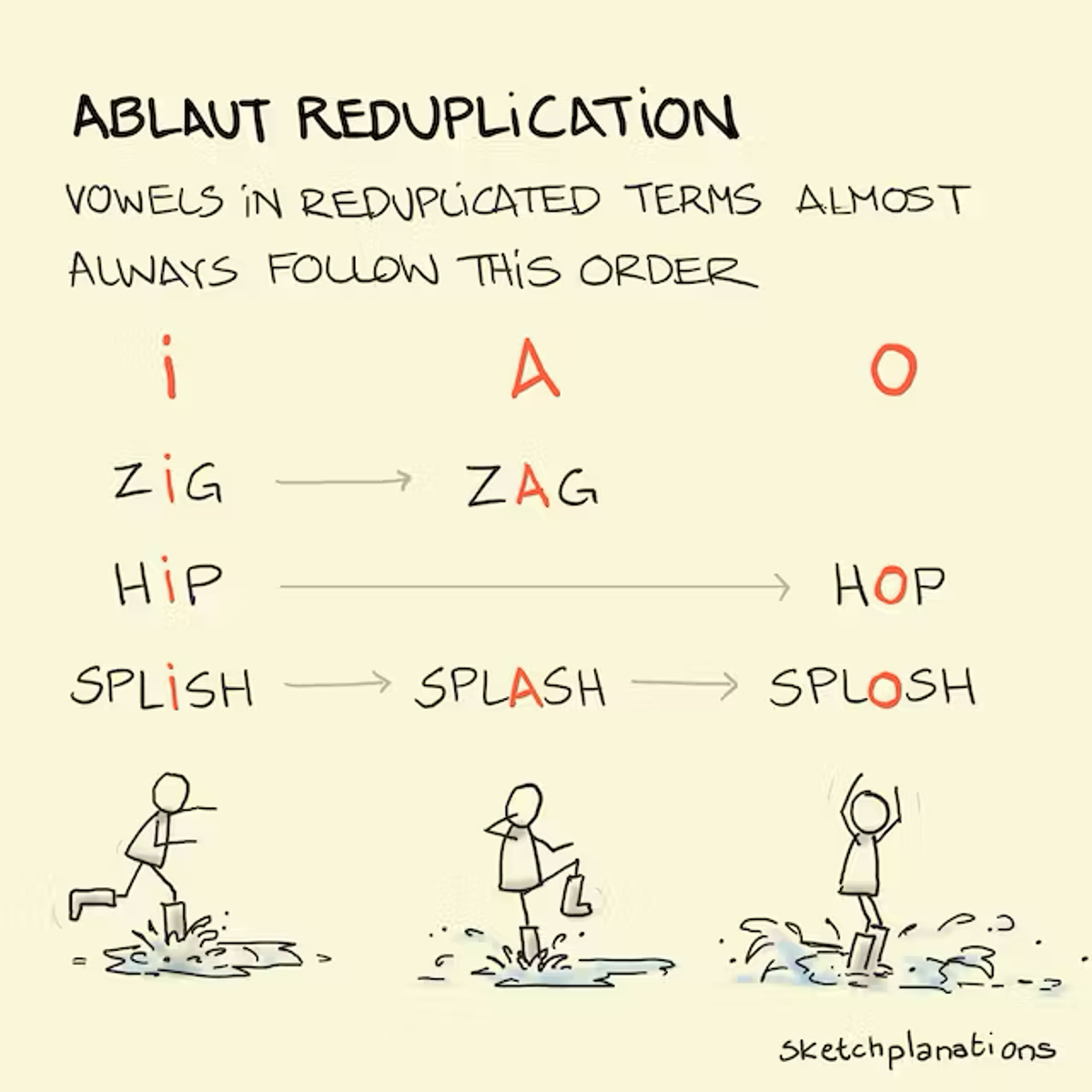

Ablaut reduplication

For some obscure reason, English speakers will almost always find a flip-flop to be more natural than a flop-flip, or a pitter-patter of tiny feet to a patter-pitter, or a tick-tock to a tock-tick. When the vowel changes in a reduplicative term — such as wishy washy or hip hop — it's known as ablaut reduplication, and the vowels almost always follow the order I-A-O. If you say them in any other way, they almost always sound weird. It's quite fun to think of examples.

I learned this neat thing from Mark Forsyth when learning about the even more surprising English grammar convention about ordering adjectives — he was explaining why we say the Big Bad Wolf (thanks to ablaut reduplication) and not the Bad Big Wolf as our other grammar convention would dictate.

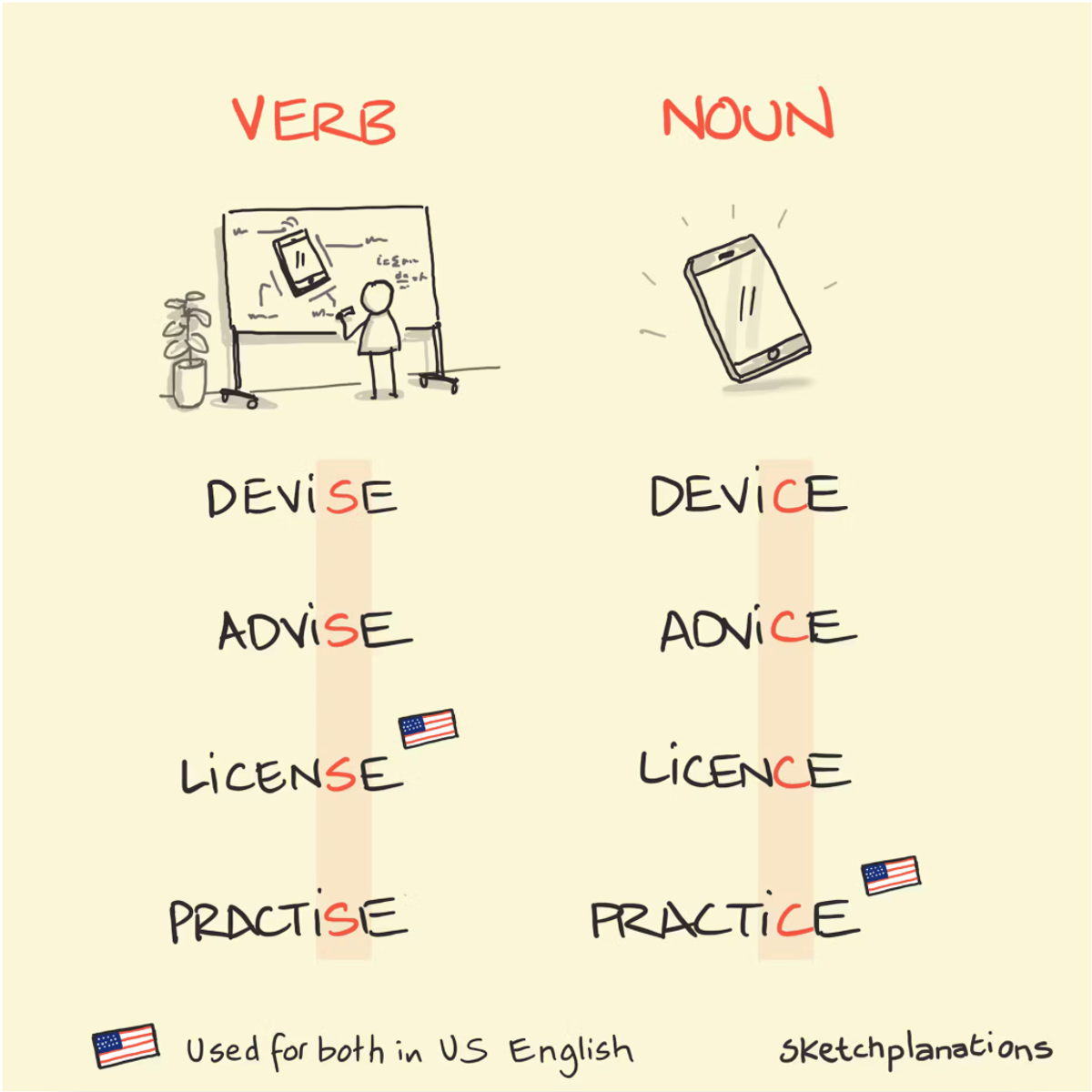

Advise vs advice and other s and c's

Is it advise or advice? Devise or device? And if you're using British English, license or licence, practise or practice?

Handily, the general practice is to use an 's' for the verb, and a 'c' for the noun. So advise is something you do, and advice is something you give.

In American English, there is only license and practice for both verbs and nouns. However, in British English, you would use license if you were licensing someone, and what they received would be a licence — with a 'c'. And in British English, you would practise when you went to practice.

Some places suggest thinking of the '-ice' at the end as ice, which is a noun. Whatever works for you.

License/licence and practise/practice are homophones.

Also see, stationary and stationery, compliment and complement, affect and effec.t

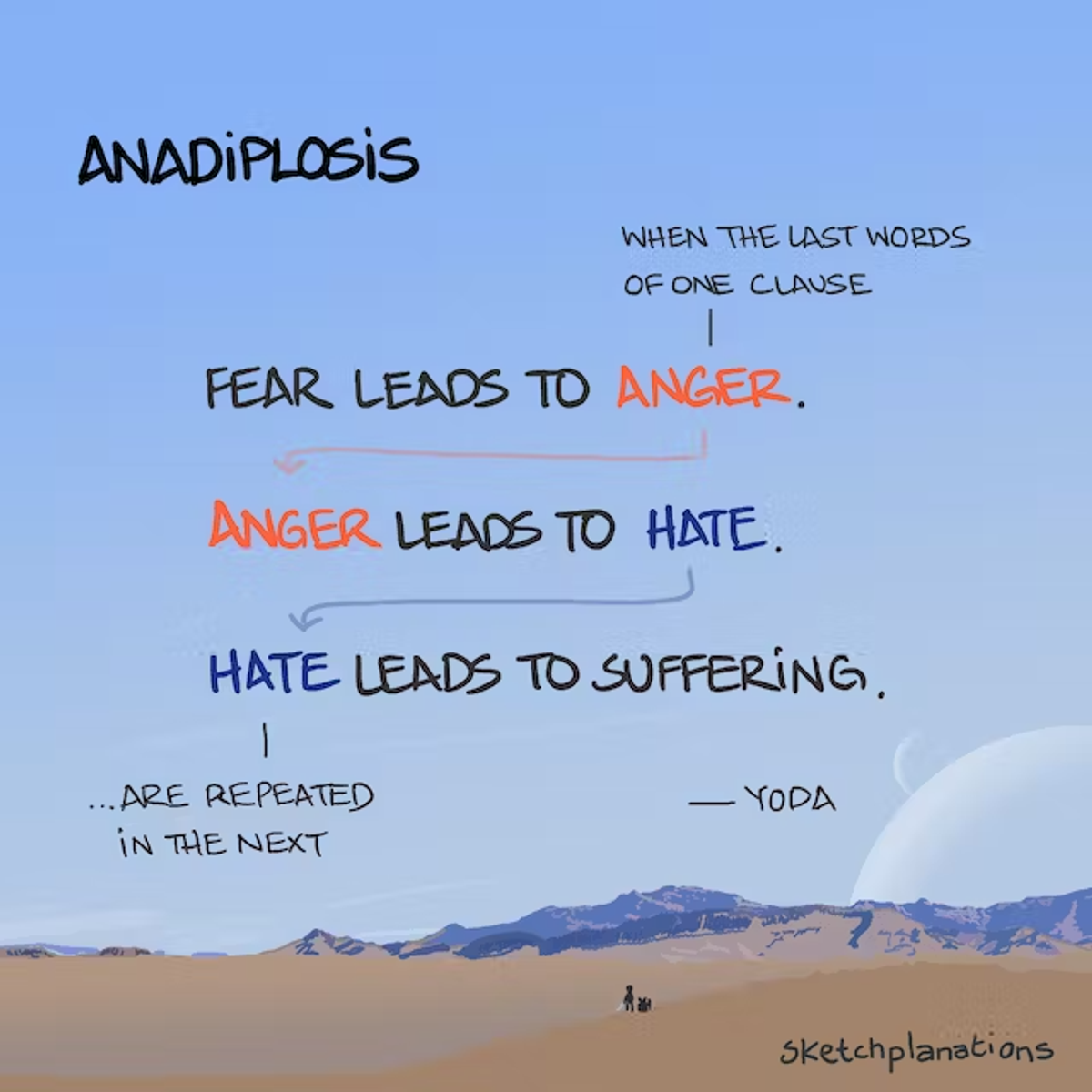

Anadiplosis

Writing has power. Power grows through repetition. And repetition, should you reuse the last words of a sentence at the start of the next, is called anadiplosis.

Like the amazing addition of alliteration, anadiplosis is a simple device to give more oomph to your words. Words that are barely changed but pack a lot more punch.

Even if you can't remember the specifics, there's something about Yoda's wisdom that makes the logic sound impeccable and irresistible and the message deep. Deep, at least partly, from anadiplosis.

"Fear leads to anger. Anger leads to hate. Hate leads to suffering."

—

I learned about anadiplosis—and pleonasm, and ordering adjectives—from the entertaining and educational, The Elements of Eloquence by Mark Forsyth. Anadiplosis is from the ancient Greek ana, meaning again, and diplous, meaning double. The Greeks were fond of their techniques for persuasive speeches.

Article:

The Work Required to Have an Opinion:

The real cost of an opinion isn’t having it—it’s doing the work required to earn it. This work is what most people avoid.

I never allow myself to have an opinion on anything that I don’t know the other side’s argument better than they do.

— Charlie Munger

The work to hold an opinion isn’t just about accumulating facts and information that support your argument.

To truly hold an opinion, you must:

- Deeply understand arguments from multiple sides

- Seek out contradictory evidence rather than hiding from it

- Test your thinking against the strongest counterarguments

- Consider how you might be fooling yourself

Someone who has done this work stands apart. Not only can they explain their position in depth and argue from multiple perspectives, but they also remain calm when challenged. They possess a rare intellectual honesty—changing their mind when evidence demands it.

We all are learning, modifying, or destroying ideas all the time. Rapid destruction of your ideas when the time is right is one of the most valuable qualities you can acquire. You must force yourself to consider arguments on the other side.

— Charlie Munger

Darwin exemplified this approach. Rather than dismissing contradictory facts, he actively collected them, knowing his theory had to account for all evidence, not just the convenient parts.

The ultimate test of understanding:

Can you argue against your position better than your best critics? If not, you haven’t earned your opinion.

This standard is expensive. It takes time. People who hold themselves to it don’t pretend to know everything. As Maimonides wisely said: “Teach thy tongue to say ‘I do not know,’ and thou shalt progress.”

The world overflows with superficial takes from people who scan headlines and regurgitate others’ thoughts. They’re easy to outthink if you don’t let them waste your time.

When faced with strongly opinionated people, ask them to write down their reasoning. Most won’t bother—revealing volumes. Those who do expose their thinking to scrutiny—fuzzy logic has nowhere to hide on paper.

The ability to do this intellectual work is rare. The payoff is enormous.

The ability to destroy your ideas rapidly instead of slowly when the occasion is right is one of the most valuable things. You have to work hard on it. Ask yourself what are the arguments on the other side. It’s bad to have an opinion you’re proud of if you can’t state the arguments for the other side better than your opponents. This is a great mental discipline.

— Charlie Munger

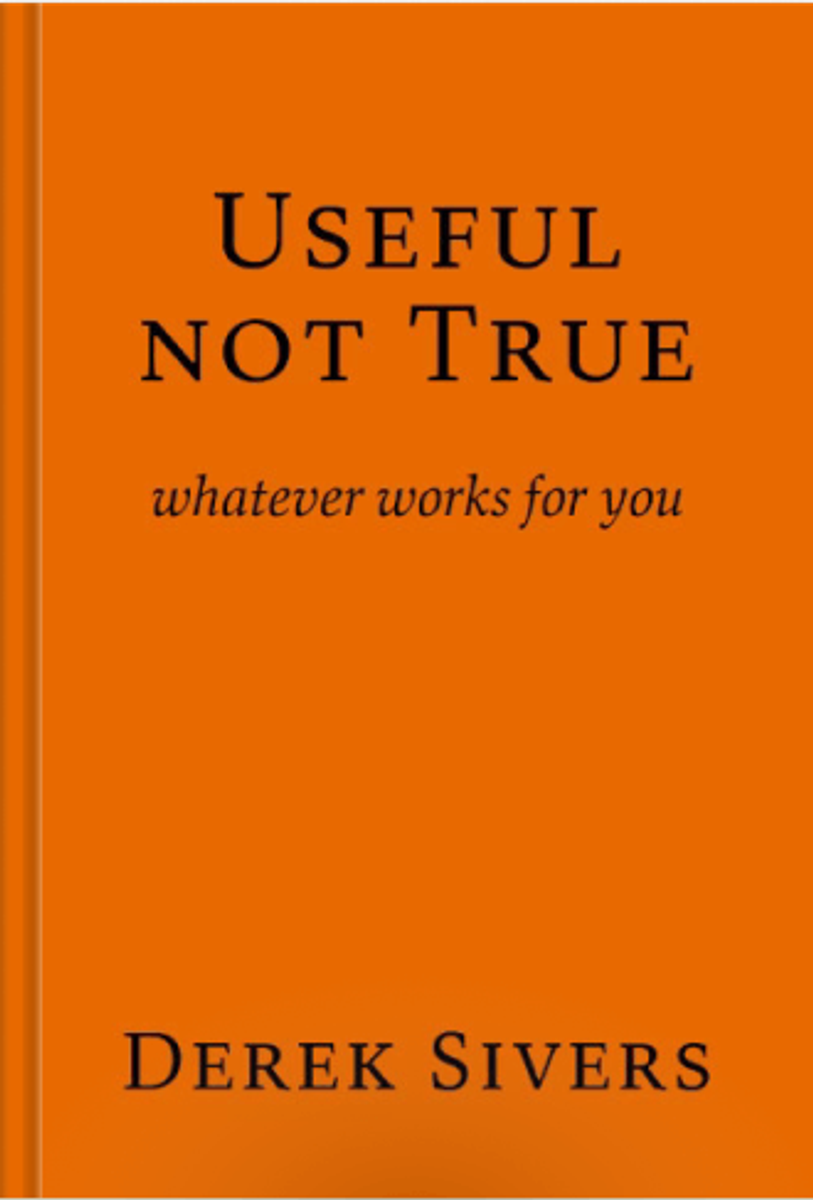

Book Recommendation:

What you will learn:

Personal effectiveness

“Useful Not True” is about reframing.

Success in anything starts with your perspective, which affects your strategy — your actions.

Your first thought (“this is a disaster”) feels true, but it’s not the only perspective.

Your first thought is an obstacle you need to get past by realising that no thoughts are necessarily true.

After your initial impulse, consider other perspectives, then choose the thought that’s more useful to you — the one that makes you take effective actions.

Understanding others

People share perspectives, not facts. They tell you how they see things.

Like someone across the world telling you the time, maybe it’s true for them, but not for you, and not for most other people.

Brains lie to their owners.

Nobody knows the real reasons why they do anything.

When someone says, “I believe…”, then whatever they say next is not a fact. No beliefs are necessarily true.

Beliefs are perspectives.

Explanations are confabulated. Obligations are wishes. Rules are arbitrary. They’re useful, but not necessarily true.

Knowing this gives you empathy, as you understand people’s incentives behind their beliefs.

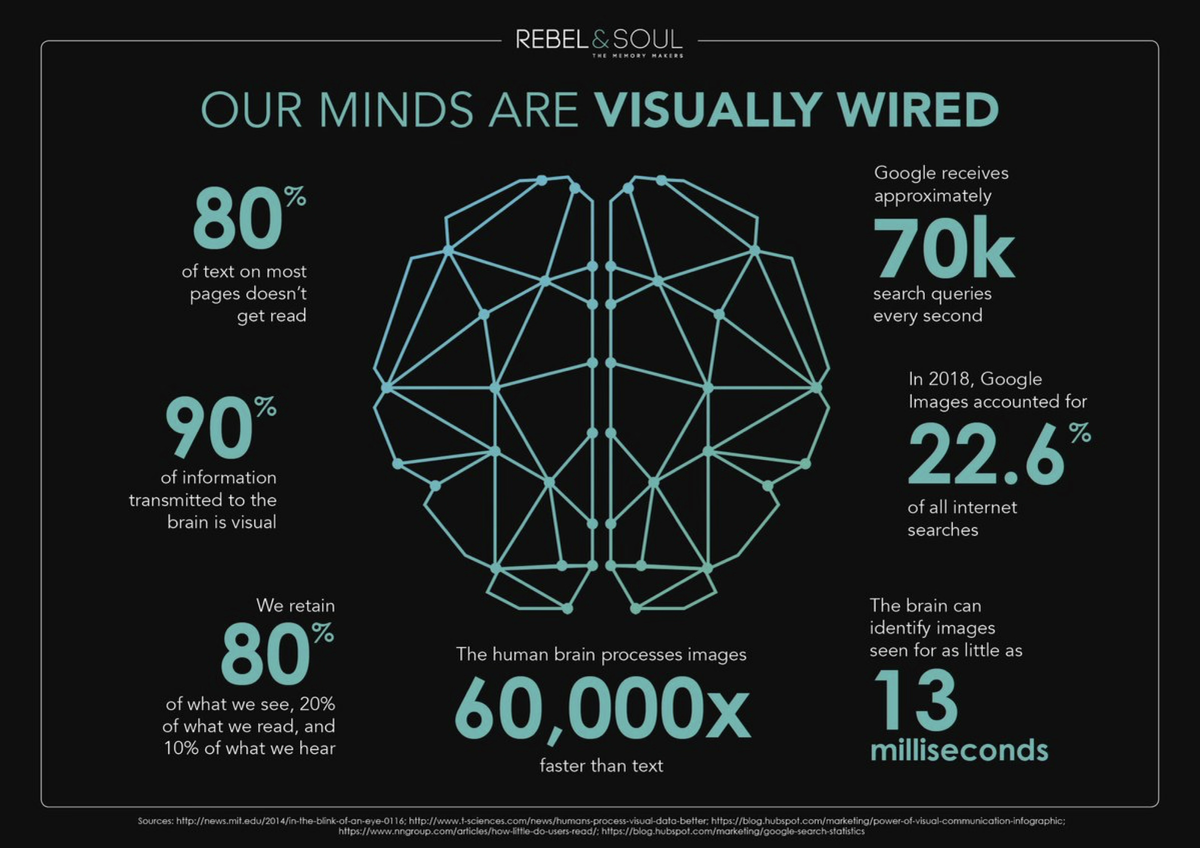

Teacher Tip:

Humans are wired for Visual.