Teachers' Page:

We start each week with a Monday Morning Meeting for staff. It's a time for information sharing, celebrating staff and children's achievements, laughter, building and strengthening the kaupapa foundations for our school, and a few tips on teaching, techie skills and even life. This page will be the place teachers can come back to if they want to revisit anything we covered in our Monday Morning Meetings.

It's really a page for teachers, but if you find anything worthwhile here for yourself, great.

Web Sites:

https://neal.fun/internet-artifacts/

Techie Tip:

Critical thinking is great, but in a world full of information, we need to learn 'critical ignoring.'

Critical ignoring’ is the ability to choose where to invest our limited capacity for attention.

Competition for our attention has accelerated over the past decade, which is why

we need strategies to help us reclaim some cognitive space.

Critical thinking helps us to evaluate the information we come across, but it may not

be enough in a digital world that contains more information than the world’s libraries

combined.

This is why we also need to learn ‘critical ignoring’ – the ability to choose what to

ignore and where to invest our limited attentional capacities.

The web is an informational paradise and a hellscape at the same time.

A boundless wealth of high-quality information is available at our fingertips right next to a

ceaseless torrent of low-quality, distracting, false and manipulative information.

The platforms that control search were conceived in sin. Their business model auctions

off our most precious and limited cognitive resource: attention. These platforms work

overtime to hijack our attention by purveying information that arouses curiosity, outrage,

or anger. The more our eyeballs remain glued to the screen, the more ads they can show us, and the greater profits accrue to their shareholders.

It is hardly surprising, therefore, all this should take a toll on our collective attention. A

2019 analysis of Twitter hashtags, Google queries, or Reddit comments found that across

the past decade, the rate at which the popularity of items rises and drops has

accelerated. In 2013, for example, a hashtag on Twitter was popular on average for 17.5

hours, while in 2016, its popularity faded away after 11.9 hours. More competition leads to

shorter collective attention intervals, leading to fiercer competition for our attention – a vicious circle.

To regain control, we need cognitive strategies that help us reclaim at least some

autonomy and shield us from the excesses, traps and information disorders of today’s attention economy.

Critical thinking is not enough.

The textbook cognitive strategy is critical thinking, an intellectually disciplined, self-guided and effortful process to help identify valid information. Students are taught to read and evaluate information closely and carefully in school. Thus equipped, they can evaluate

the claims and arguments they see, hear, or read. No objection. The ability to think critically is essential.

But is it enough in a world of information overabundance and gushing sources of

disinformation? The answer is “No” for at least two reasons.

First, the digital world contains more information than the world’s libraries combined.

Much of it comes from unvetted sources and lacks reliable indicators of trustworthiness.

Critically thinking through all the information and sources we come across would utterly

paralyse us because we would never have time actually to read the valuable information we painstakingly identify.

Second, investing critical thinking in sources that should have been ignored in the first

place means that attention merchants and malicious actors have been gifted what they wanted: our attention.

Critical ignoring to make information management feasible.

So, what tools do we have at our disposal beyond critical thinking? In our recent article,

we – a philosopher, two cognitive scientists and an education scientist – argue that as

much as we need critical thinking, we also need critical ignoring.

Critical ignoring is the ability to choose what to ignore and where to invest one’s limited

attentional capacities. Critical ignoring is more than just not paying attention – it’s about

practising mindful and healthy habits in the face of information overabundance.

We understand it as a core competence for all citizens in the digital world.

Without it, we will drown in a sea of information that is, at best, distracting and, at worst, misleading and harmful.

Tools for critical thinking

Three main strategies exist for critical ignoring. Each one responds to a different type of

noxious information.

In the digital world, self-nudging aims to empower people to be citizen “choice architects”

by designing their informational environments in ways that work best for them and

constrain their activities in beneficial ways. We can, for instance, remove distracting and

irresistible notifications. We may set specific times for receiving messages, thereby creating pockets of time for concentrated work or socialising. Self-nudging can

also help us take control of our digital default settings, for instance, by restricting the use

of our personal data for targeted advertisement purposes.

Lateral reading is a strategy that enables people to emulate how professional fact-checkers establish the credibility of online information. It involves opening new

browser tabs to search for information about the organisation or individual behind a site

before diving into its contents. After consulting the open web, skilled searchers only gauge whether expending attention is worth it. Before critical thinking can begin, the first

step is to ignore the lure of the site and check out what others say about its alleged

factual reports. Lateral reading thus uses the power of the web to check the web.

Most students fail at that task. Past studies show that, when deciding whether a source

should be trusted, students (and university professors) do what years of school have

taught them to do – they read closely and carefully. Attention merchants, as well as

merchants of doubt, are jubilant.

Online, looks can be deceiving. Unless one has extensive background knowledge, it is

often very difficult to figure out that a site, filled with the trappings of serious research,

peddles falsehoods about climate change or vaccinations or any variety of historical

topics, such as the Holocaust. Instead of getting entangled in the site’s reports and

professional design, fact-checkers exercise critical ignoring. They evaluate the site by

leaving it and engaging in lateral reading instead.

The do-not-feed-the-trolls heuristic targets online trolls and other malicious users who

harass, cyberbully or use other antisocial tactics. Trolls thrive on attention, and deliberate

spreaders of dangerous disinformation often resort to trolling tactics. One of the main

strategies that science denialists use is to hijack people’s attention by creating the

appearance of a debate where none exists. The heuristic advises against directly

responding to trolling. Resist debating or retaliating. Of course, this strategy of critical

ignoring is only a first line of defence. It should be complemented by blocking and

reporting trolls and by transparent platform content moderation policies, including

debunking.

These three strategies are not a set of elite skills. Everybody can make use of them, but

educational efforts are crucial for bringing these tools to the public.

Critical ignoring as a new paradigm for education

The philosopher Michael Lynch has noted that the Internet “is both the world’s best fact-

checker and the world’s best bias confirmer – often at the same time.”

Navigating it successfully requires new competencies that should be taught in school.

Without the competence to choose what to ignore and where to invest one’s limited

attention, we allow others to seize control of our eyes and minds. Appreciation for the

importance of critically ignoring is not new but has become even more crucial in the digital world.

As the philosopher and psychologist William James astutely observed at the beginning of

the 20th century: “The art of being wise is the art of knowing what to ignore.”

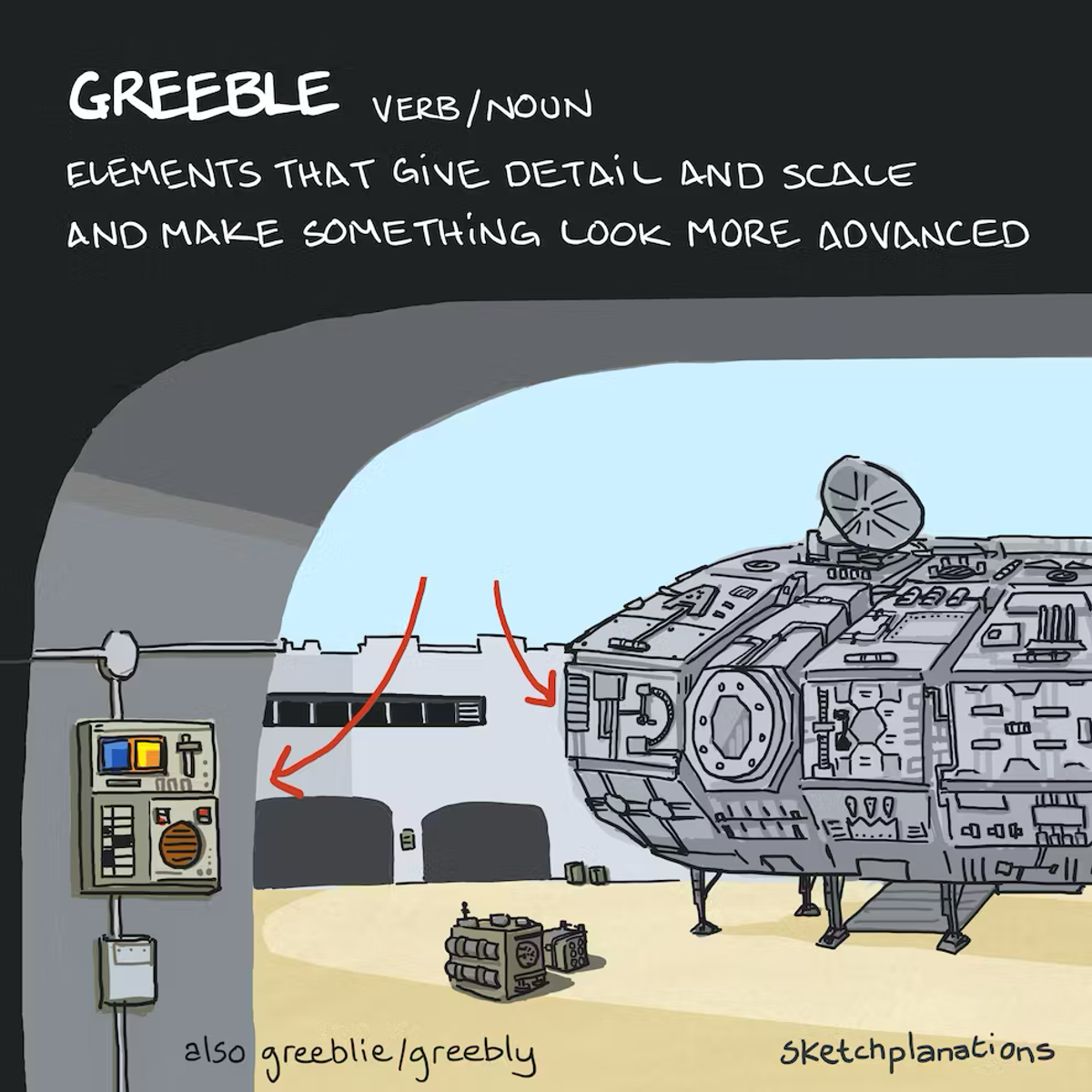

Sketchplanations

A greeble, greeblie or greebly, is the name for the small elements that add detail and scale to models and, often, help make them look more advanced and realistic. Greeble can be both a verb and a noun.

Greeble or greeblie, George Lucas' term, originated on the early Star Wars sets when creating the impressively detailed and realistic models. You can take a simple ship, wall or rooftop, and by adding switches, boxes, cabling, lights and buttons, hey presto, there's a whole lot more technology involved. You can add greebles, or greeblies, to something, or you can greeble it.

A common modelmaking technique for adding elements and greebles to make a design look realistic and sophisticated is to scavenge from existing model kits. Borrowing other parts and repurposing them on a new model is called kit-bashing. Speaking personally, it's also very satisfying making up greebles to add to a LEGO build (MOC—My-Own-Creation)—sometimes the most fun part.

Here's Adam Savage, an ex-Star Wars modelmaker discussing greeblies and kit-bashing (video) or an ILM (Industrial Light and Magic) model shop greeblie (video) used on Star Wars Episode 2. Greebles also make an appearance in the fascinating documentaries about the making of the Star Wars films, Empire of Dreams, and the making of episode 9, The Skywalker Legacy. Sometimes, the making-of is more interesting than what was made. I remember the same feeling watching the making of the Lord of the Rings films, too.