Teaching & Learning Page:

Web Pages:

https://szupie.github.io/supercontinents/

Hands down my favourite internet browser of all time. I was a very early adopter and have been nothing but impressed. The Browser Company is always innovating, and you really should check it out.

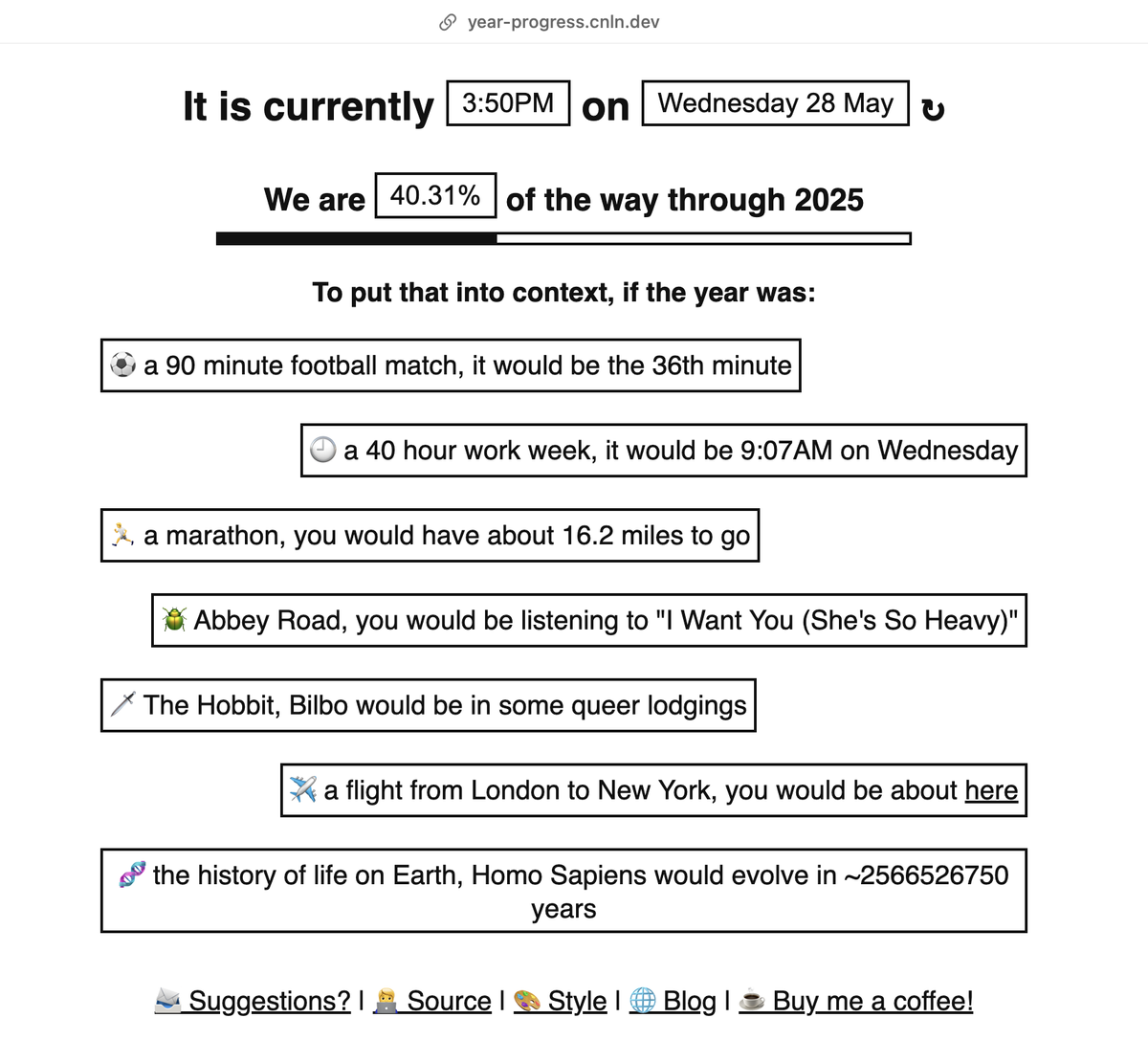

https://year-progress.cnln.dev/

Techie Tips:

Sketches:

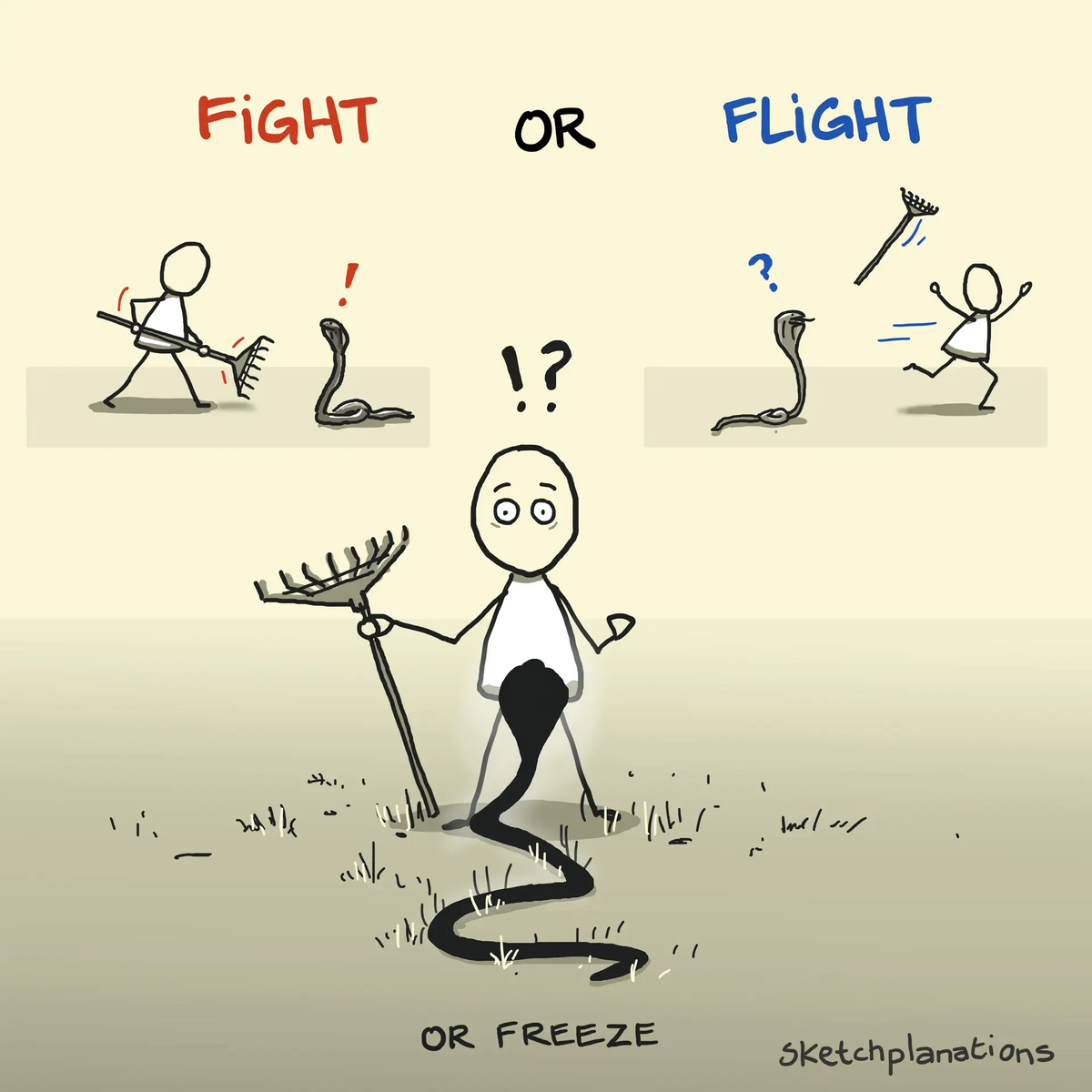

The fight-or-flight response is our body's automatic and ancient response to perceived threats or danger. This innate physiological response in animals and humans prepares us to either confront a threat (fight) or flee from it (flight). This mechanism, often referred to as entering fight-or-flight mode, likely played a critical role in our survival.

Face to face with a tiger

At the annual Wildlife Photographer of the Year Awards, I saw an astonishing photo of a tiger surprising workers in a field (Tiger Run by Nejib Ahmed ). Everyone is in flight mode except one man, much braver than me, who perhaps through instinct has stood to fight, staring down the approaching tiger with a long stick. The photo is captivating in its drama and struck me as a perfect fight-or-flight example in action. Thankfully, no one—including the tiger—was hurt in this instance.

The adrenalin that can flood our bodies during such moments may sometimes give us strength to do what we didn't expect, surprising ourselves with what we are capable of—Nicola Morgan, when discussing the amazing teenage brain , gives an example of her leaping a 5ft fence and looking back with amazement. Sudden strength or speed like this is a well-known fight-or-flight symptom.

Reptilian brain, Lizard brain

The fight-or-flight response is linked to theories about how different parts of the brain developed during our evolution. Modern research has corrected some aspects of this idea, but the basic concept remains.

The most primitive parts of the brain—those we may share with, say, dinosaurs—are responsible for automatic behaviours like protecting territory, aggression, fear and fending off danger. This is often referred to as the reptilian brain or lizard brain. These brain areas are key to our survival instincts and play a critical role in activating fight-or-flight mode.

Years of evolution since then have given us brain structures like the limbic system, which is responsible for our emotions and social behaviours. The amygdala, part of the limbic system, is especially important in triggering fear and the fight-or-flight response.

Later, the neocortex evolved, enabling humans to assess threats rationally, solve problems, and make decisions—giving us more control over how we respond to fear or anxiety.

The response, also illustrated by the snake rearing up in the sketch, is a fallback to our oldest instincts from the oldest parts of our brain when faced with a threat, so the theory goes.

Freeze, Flight, Fight, Fright

Fight-or-flight psychology, coined by physiologist Walter Cannon in 1915, is only part of a broader spectrum of acute stress responses. A more accurate sequence we experience may be freeze, flight, fight, or fright .

Freeze:

Our immediate reaction to danger might be to "stop, look, listen," remaining hyper-vigilant while we assess the threat, and perhaps hope by not moving, the dinosaur won't spot us.

Flight:

We may flee the situation to safety.

Fight:

If escape isn't possible, we might fight back, as shown by the brave individual in the tiger photo.

Fright:

This might include panic and immobility, playing dead in case a predator decides we're not worth eating after all.

As you see, the updated list continues with excellent alliteration, which no doubt helped make the idea sticky in the first place (other proposals add fawn, faint, flock and more).

When Fight-or-Flight Doesn't Help

While the tiger scenario shows our ancient brain instincts at work, most modern-day situations don't involve life-or-death threats. However, we may still enter fight-or-flight mode during stressful, anxiety-inducing moments, such as public speaking, a challenging work interaction, or a difficult conversation.

In these cases, our age-old reactions may not serve us well. The same ancient brain that would help us survive a predator may now cause us to avoid daunting tasks. Whether it's a work presentation, a cold sales call, or confronting a personal issue, we may feel the urge to retreat from the action and get a snack from the kitchen instead.

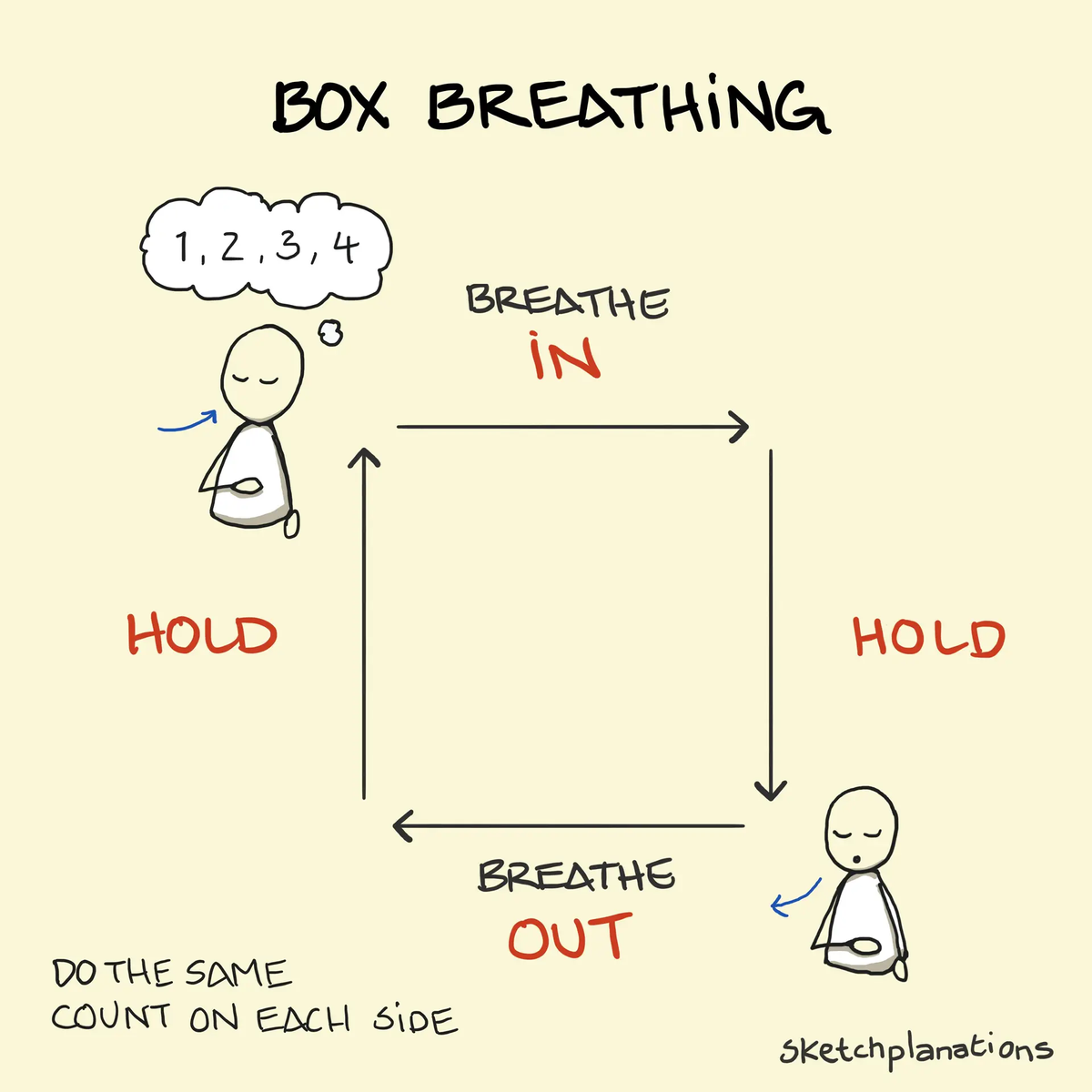

When our ancient instincts—so finely tuned for survival—are no longer serving us in modern situations, it's helpful to pause and let our higher-order thinking take the lead. Techniques like box breathing or meditation help calm the body and mind, allowing us to move beyond fear and resistance. By doing so, we can overcome the automatic urge to "fight or flight," or even freeze or fright, and instead respond with clarity, control, and confidence.

Box breathing can help us focus on the present, reduce stress and anxiety by lowering cortisol levels, and generally relax and be calm.

Box breathing involves four steps repeated in sequence, each for an equal count: 1 Breathe in

2 Hold your breath

3 Breathe out

4 Hold your breath

It's called box breathing or square breathing, as the four equal steps are like the sides of a virtual box. Counting to four is typical, though it can be more or less.

Because of box breathing's simplicity and effectiveness, it's also used by the Navy SEALs—for example, ex-Navy SEAL Mark Divine can lead you through box breathing on video.

I find meditation surprisingly difficult, and the steps and simple counting of box breathing help me stay focused and free of distraction, as well as any other technique. Even a few cycles of box breathing before a difficult conversation, a public talk, or after a challenging spell with our children helps me stay cool and be better.

Article:

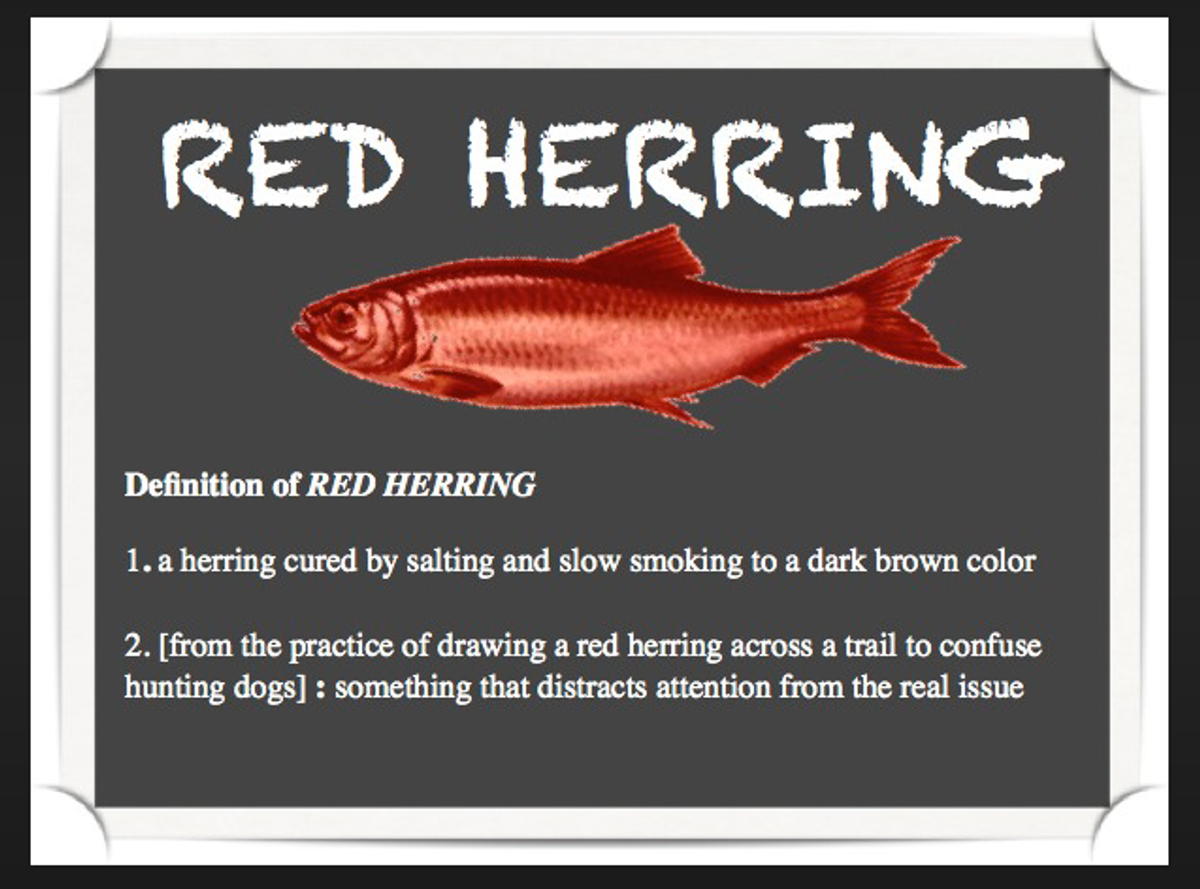

The Red Herring Fallacy:

There's an interesting logical fallacy I was recently reminded of called the red herring fallacy — when someone tries to divert our attention from the core topic of discussion to an irrelevant point. It might sound familiar because you might have had discussions at work or with a personal acquaintance that went awry. But why is learning about this fallacy useful ? Developing the ability to identify a red herring when it's introduced into a discussion helps us redirect the conversation to a productive path. For example, a senior at work might not have a clear answer to your question and tries to redirect the conversation to a vague proposition not to look "less informed".

A higher-up at your company, unable to address your concerns about a project or campaign, throws big but irrelevant numbers to make their request seem valid.

When asked about a local community issue, a politician might redirect the conversation to a broader, unrelated problem or a hypothetical scenario to dodge the question altogether.

I've had a colleague at work with whom I'd start a discussion related to work and end up discussing mechanical keyboards or some other gadget an hour later. In such cases, understanding that there's a red herring fallacy at play can:

1. Help us drive a meeting or debate towards a resolution rather than wasting time on an unrelated topic.

2. Understand when an authority figure is trying to dodge a question because they don't have a clear or safe answer, such as a CEO attempting to avoid a potential layoff question in a company meeting, as an honest answer might create chaos.

So, the next time you sense a discussion is going the wrong way, point out the uninvited red herring to bring it back on track.

And where did it originate?

Book Recommendation: