Teaching & Learning Page:

Web Pages:

https://www.amnh.org/explore/ology/brain/optical-illusions-and-how-they-work?

https://www.poemgenerator.com/

https://time.com/collections/100-most-influential-people-2025/

Techie Tips:

There’s No Easy Button for the AI Revolution in Education

As AI rapidly reshapes our world, here’s something I hope educators will seriously consider:

Shortcut tools—those that spit out lesson plans or activities without requiring any real engagement—may feel helpful in the short term. But they risk robbing educators of something far more important: the opportunity to understand and harness the true power of AI.

This moment demands more than plug-and-play solutions. It demands literacy. And real AI literacy begins with working directly with large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT or Gemini.

Why? Because only through direct interaction do teachers begin to notice what’s changing—and what it means.

Today’s models aren’t what they were last year. LLMs are rapidly evolving: they’re reasoning more deeply, researching more effectively, and generating nearly flawless visuals. The AI is growing up. And if we want teachers to lead in this next era, they must grow with it.

Initially, educators sought simplicity. Prompting was awkward. Outputs were hit or miss. Easy-button tools made sense, and I understand why teachers used them.

But that’s no longer the case.

The relationship between teacher and AI has shifted. It’s now a partnership. When teachers engage directly with an LLM, the model begins to learn from them, reflecting their pedagogical approach, tone, and values. Over time, AI becomes an extension of the teacher’s own thinking, helping them create lesson plans, write rubrics, personalise communication, and more—all aligned with their unique voice and vision.

Shortcut tools can’t do that. They generate disconnected, one-off outputs. They don’t learn. They don’t grow. They don’t collaborate.

And if teachers don’t understand this shift, how can they effectively prepare students for what’s to come?

While it was necessary to make AI accessible initially, we are now at a crossroads. The question is no longer “How can we make AI easier?” It’s “How can we empower AI?”

Staying stuck on simplified tools keeps teachers at the surface. It’s a “Teachers Pay Teachers” version of innovation. It feels helpful—but it’s hollow.

While there is certainly a hybrid approach, we need to go deeper and keep evolving.

This isn’t about replacing teachers. It’s about amplifying them.

However, amplification only occurs when educators are given the opportunity to think with AI, not just generate from it.

The time for easy buttons has passed. The time for empowered, AI-literate educators is now something we all must be thinking about.

AI Self Assessment for Teachers:

🎓 Do you believe students need to learn about AI?

Why or why not—and how would you approach that learning in your classroom?

🤔 What it reveals:

Your awareness of the importance of AI literacy and whether you see it as an essential component of modern education, not just an add-on.

💭What role do you think AI can play in helping educators and students become better thinkers?

🤔What it reveals:

Insight into your views on metacognition, reflection, and how AI might be used to offload routine tasks in the service of deeper thinking and problem solving.

🤖Think about a time you used AI in your personal or professional life. What did it help you discover, solve, or rethink?

🤔What it reveals:

Your openness to innovation, willingness to explore new tools, and how they reflect on technology’s role in thinking and learning.

📚In your view, how is AI reshaping what it means to be literate today—and how does that influence the way you plan and deliver learning?

🤔What it reveals:

Whether you are thinking critically about literacy as more than reading and writing—understanding systems, questioning outputs, and integrating ethical decision-making into your practice.

🤖When a student uses AI on an assignment, how would you determine whether it’s a case of dishonesty or resourceful thinking?

🤔What it reveals:

Your approach to nuance, innovation, and how you define authentic learning in a tech-integrated environment.

Sketches:

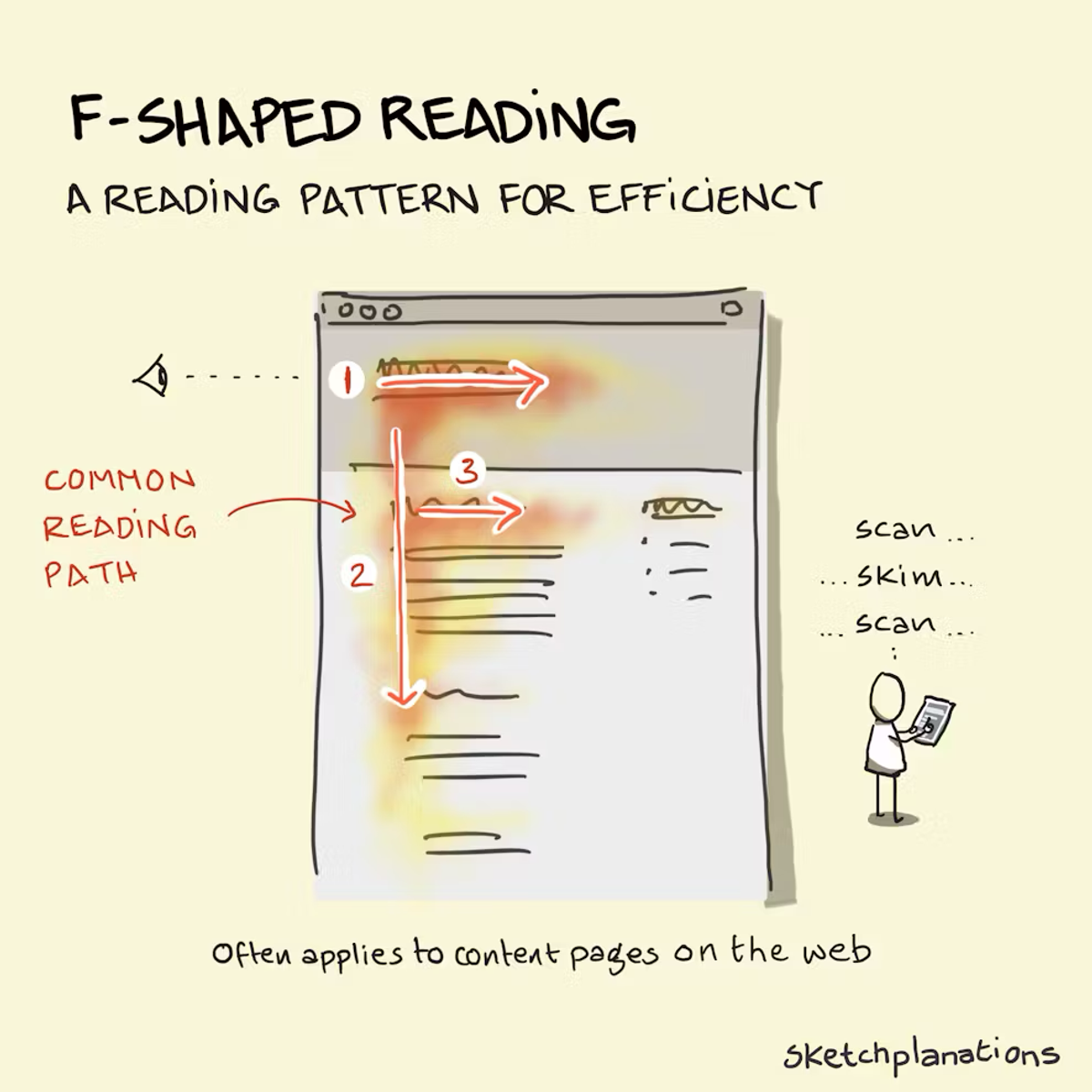

Many of us absorb and sift through huge quantities of information on the web daily. We've trained ourselves to quickly pull out the most important information and decide if the rest is worth our time. When this happens, which is most of the time, people commonly use F-Shaped Reading.

What is F-Shaped Reading?

F-Shaped Reading is a pattern seen in eye-tracking studies of people reading content on the web that seems to follow the shape of an F. That looks like scanning the top words most, maybe making it to the end of a headline. Then moving down the left-hand side and heading right again when we hit another sub-head or line that draws our attention.

In languages that read right-to-left, you can see a reverse F-shape.

We don't always read in an F-shape. There are several other common text-scanning patterns, such as spotted, layer-cake, marking, bypassing or commitment patterns—getting stuck in and reading the whole thing. However, an F-shaped reading, first identified around 2006, is still common and used on mobile devices.

F-Shaped Reading is about reading content. It's not how we might scan a shiny new web page with fancy navigation and CTAs (Calls To Action).

Why an F-Shape?

F-Shaped Reading means that your headline and your first sub-head matter a lot. And also, the content on the left matters more as a way to draw people into your work.

But it doesn't have to be this way. An F-shape arises because we're trying to be efficient and decide if this page is worth more of our time.

It's hard to get that from a block of text, so we improvise—getting an idea of the content areas from the headlines and trying to see which content blocks, if any, are relevant to read by scanning quickly down the page.

I'm not too proud to admit that you may be scanning this.

Improving on F-Shaped Reading and Helping Our Readers

To my knowledge, this observation is from the NN Group, which also has a comprehensive article on F-Shaped Reading.

They have a useful list of antidotes, which I paraphrase below, together with a few additions of my own:

- Put the most important information first.

- Structure with headings and subheadings.

- Front-load words in headings and bullet points with the most information (check the first word of the titles in this post).

- Group related content visually — see 7 Gestalt principles.

- Highlight important content.

- Ensure links have information-bearing words (information scent).

- Use lists.

- Cut unnecessary content.

- Avoid big blocks of text and use a sketch instead.

- Use visuals and captions as gateways to content.

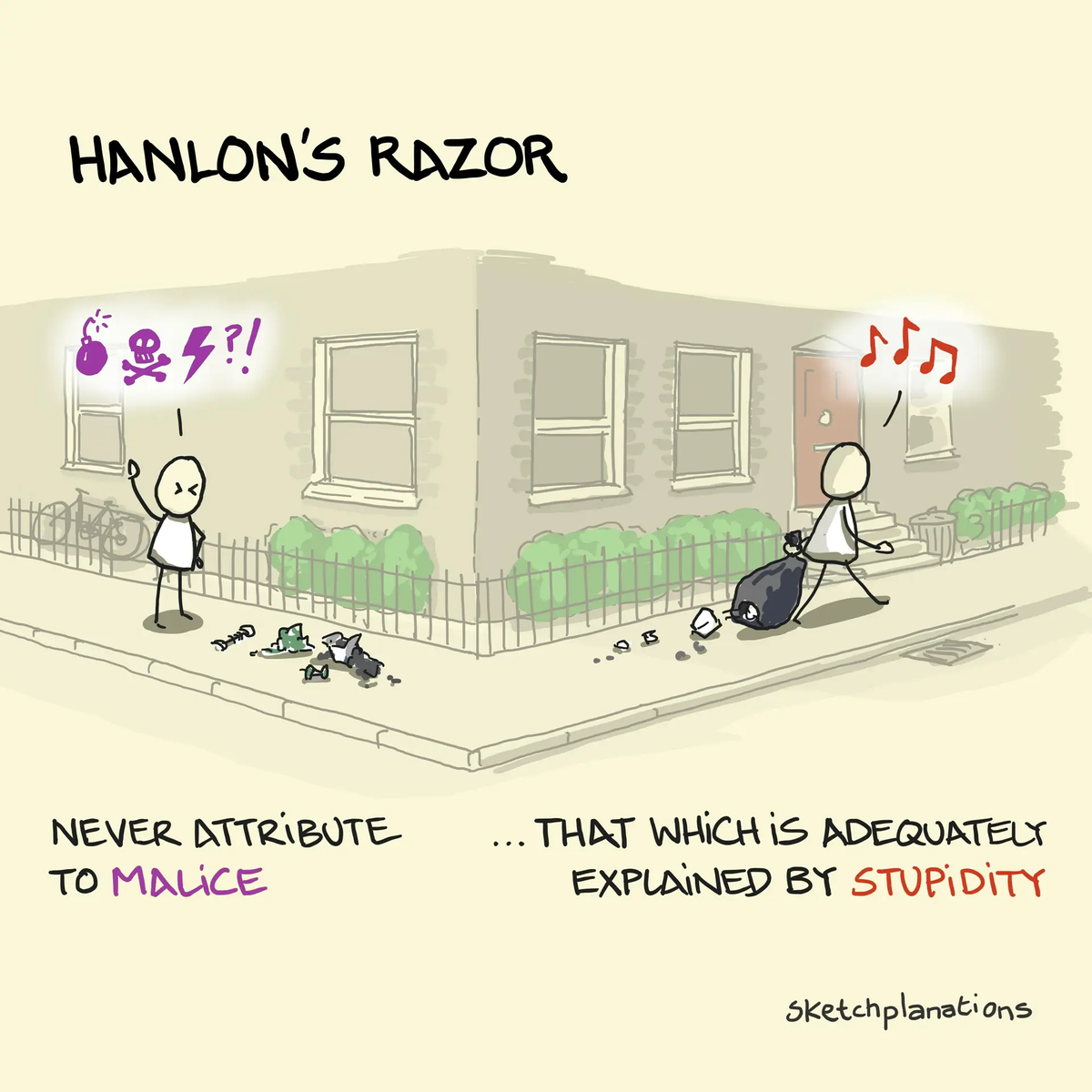

Hanlon's Razor is the adage: "Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity."

Or sometimes, "Never attribute to malice what can be attributed to incompetence."

It appears in a similar form by the inimitable Johann Wolfgang von Goethe as, "And I have again observed, my dear friend, in this trifling affair, that misunderstandings and neglect occasion more mischief in the world than even malice and wickedness. At all events, the latter two are less frequent in The Sorrows of Young Werther . The same sentiments are also shared by William James, Churchill, and H.G. Wells. More recently, Douglas Hubbard gave a more modern version in his book The Failure of Risk Management: Why It's Broken and How to Fix It: "Never attribute to malice or stupidity that which can be explained by moderately rational individuals following incentives in a complex system."

The mistake of assuming bad intentions was brought home to me when I puzzled why people kept leaving paper towels in the sinks of the bathrooms at university. How hard is it to put them in the bin?? A year after assuming my fellow students were either lazy or inconsiderate or both, I was washing my hands when another student dried his hands on the towel, walked to the door, opened it by covering the handle with the paper towel — presumably to avoid the germs — and then aimed his paper towel at the bin which was between the sinks. He missed, and it landed in the sink as he walked off down the corridor. Suddenly, it was clear to me that the hygiene of the door handle was higher in consideration of towel-in-the-sink people than whether or not their towel hit their target (and whether it was worth checking if their towel had hit the bin). It made sense. Someone later moved the bin next to the door, and it didn't happen again.

Besides towels in sinks, I've seen people get mad at others pushing in line when the pushers-in didn't realise other people were queuing. I've seen drivers shouting at another driver who's in blissful ignorance of the trouble they've caused. I've seen agents blamed for terrible customer service when the system is at fault, and customer service blames users when the product is at fault. I've seen people despairing at others leaving litter in the park or on the street when animals had dragged out the mess overnight. I've seen people vilified for not moving down on a train when they weren't aware of the squeeze at the other end. And, usually, I think people aren't smart or capable enough, or in fact wicked enough, to carry out the conspiracies that people credit them with. Very often, it's the person who assumes bad intentions and gets mad who suffers the most.

To be sure, there are different degrees of negligence. We can all make mistakes, but if you're doing your taxes, it's not okay to make a mistake because you didn't read the instructions. If you're standing on a busy train, you owe it to others to be aware that you may be blocking an aisle, and we should do our best to make sure our rubbish stays where we put it. But none of us are perfect, and so often I think Hanlon's Razor has some truth to it.

Perhaps a better formulation of Hanlon's Razor would be, "Before attributing to malice, try attributing to incompetence." But I'm not a fan of the wording with 'stupidity' or 'incompetence'. Awareness is so often the necessary start and what's missing.

Since posting this, a few people also shared with me Clarke's Corollary: "Any sufficiently advanced incompetence is indistinguishable from malice." And another relevant name for a similar situation is Cock-up Over Conspiracy .

Source for Hanlon's Razor

Hanlon's Razor, which encourages us first to consider innocent mistakes rather than assuming ill will, was a submission to Murphy's Law, Book Two: More Reasons Why Things Go Wrong, by Arthur Bloch (p. 52). Murphy's Law is "If anything can go wrong, it will." I've also previously covered Muphry's Law, where, when criticising spelling or grammar, you will make a spelling or grammar mistake yourself.

Article:

No, You Don’t Get an A for Effort

By Adam Grant

Dr. Grant, a contributing Opinion writer, is an organisational psychologist at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

After 20 years of teaching, I thought I’d heard every argument in the book from students who wanted a better grade. But recently, at the end of a weeklong course with a light workload, multiple students had a new complaint: “My grade doesn’t reflect the effort I put into this course.”

High marks are for excellence, not grit. In the past, students understood that hard work was not sufficient; an A required great work. Yet today, many students expect to be rewarded for the quantity of their effort rather than the quality of their knowledge. In surveys, two-thirds of college students say that “trying hard” should be a factor in their grades, and a third think they should get at least a B just for showing up at (most) classes.

This isn’t Gen Z’s fault. It’s the result of a misunderstanding about one of the most popular educational theories.

More than a generation ago, the psychologist Carol Dweck published groundbreaking experiments that changed how many parents and teachers talk to kids. Praising kids for their abilities undermined their resilience, making them more likely to get discouraged or give up when they encountered setbacks. They developed what came to be known as a fixed mindset: They thought that success depended on innate talent and that they didn’t have the right stuff. To persist and learn in the face of challenges, kids needed to believe that skills are malleable. And the best way to nurture this growth mindset was to shift from praising intelligence to praising effort.

The idea of lauding persistence quickly made its way into viral articles, best-selling books and popular TED talks. It resonated with the Protestant work ethic and reinforced the American dream that with hard work, anyone could achieve success.

Psychologists have long found that rewarding effort cultivates a strong work ethic and reinforces learning. That’s especially important in a world that often favours naturals over strivers — and for students who weren’t born into comfort or don’t have a record of achievement. (And it’s far preferable to the other corrective: participation trophy culture, which celebrates kids for just showing up.)

The problem is that we’ve taken the practice of celebrating industriousness too far. We’ve gone from commending effort to treating it as an end in itself. We’ve taught a generation of kids that their worth is defined primarily by their work ethic. We’ve failed to remind them that working hard doesn’t guarantee doing a good job (let alone being a good person). And that does students a disservice.

In one study, people filled out a questionnaire to assess their grit. Then they were presented with puzzles that — secretly — had been designed to be impossible. If there wasn’t a time limit, the higher people scored on grit, the more likely they were to keep banging away at a task they were never going to accomplish.

This is what worries me most about valuing perseverance above all else: It can motivate people to stick with bad strategies instead of developing better ones. With students, a textbook example is pulling all-nighters rather than spacing out their studying over a few days. If they don’t get an A, they often protest.

Of course, grade grubbing isn’t necessarily a sign of entitlement. If many students are working hard without succeeding, it could be a sign that the teacher is doing something wrong — poor instruction, an unreasonable workload, excessively difficult standards or unfair grading policies. At the same time, it’s our responsibility to tell students who burn the midnight oil that although their B– might not have fully reflected their dedication, it speaks volumes about their sleep deprivation.

Teachers and parents owe kids a more balanced message. There’s a reason we award Olympic medals to the athletes who swim the fastest, not the ones who train the hardest. What counts is not sheer effort but the progress and performance that result. Motivation is only one of multiple variables in the achievement equation. Ability, opportunity and luck count, too. Yes, you can get better at anything, but you can’t be great at everything.

The ideal response to a disappointing grade is not to complain that your diligence wasn’t rewarded. It’s to ask how you could have gotten a better return on your investment. Trying harder isn’t always the answer. Sometimes it’s working smarter, and other times it’s working on something else altogether.

Every teacher should be rooting for students to succeed. In my classes, students are assessed on the quality of their written essays, class participation, group presentations and final papers or exams. I make it clear that my goal is to give as many A’s as possible. But they’re not granted for effort itself; they’re earned through mastery of the material. The true measure of learning is not the time and energy you put in. It’s the knowledge and skills you take out.

Book Recommendation:

From the author of the global bestseller, 'The Power of Habit'.

This is not just a riveting read about how to understand others better. It's also a revealing look at how to be understood!'

- Adam Grant

If you want to improve your communication skills at work and in life, this book is the place to start.

- Arthur C. Brooks

Professor, Harvard Business School, and #1 New York Times bestselling author.

Who and what are supercommunicators? They're the people who can steer a conversation to a successful conclusion. They can talk about difficult topics without giving offence. They know how to make others feel at ease and share what they think. They're brilliant facilitators and decision-guiders. How do they do it?

In this groundbreaking new book, Charles Duhigg unravels the secrets of the supercommunicators to reveal the art - and the science - of successful communication. He unpicks the different types of everyday conversation and pinpoints why some go smoothly while others swiftly fall apart. He reveals the conversational questions and gambits that bring people together. And he shows how even the trickiest of encounters can be turned around. In the process, he shows why a ClA operative won over a reluctant spy, how a jury member got his fellow jurors to view an open-and-shut case differently, and what a doctor found they needed to do to engage with a vaccine sceptic. Above all, he reveals the techniques we can all master to successfully connect with others, however tricky the circumstances. Packed with fascinating case studies and drawing on cutting-edge research, this book will change the way you think about what you say, and how you say it.