Teaching & Learning Page:

Web Pages:

https://www.littleanswers.space

Techie Tips:

Sketches:

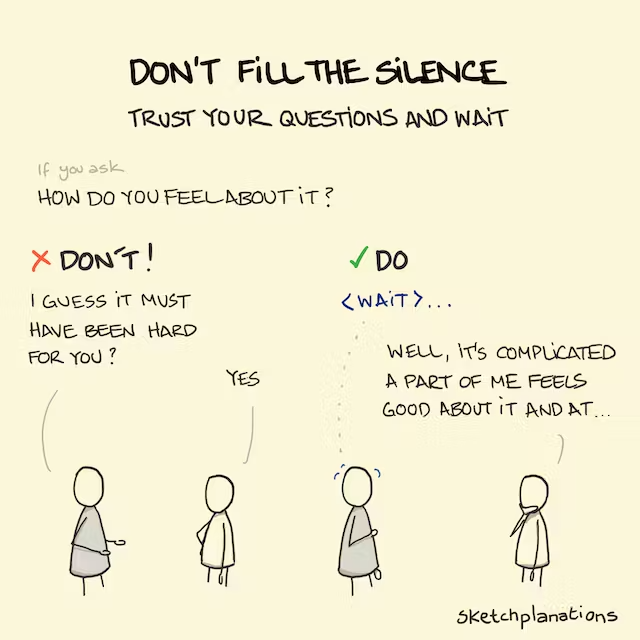

Don't Fill The Silence

It's easy to want to fill an awkward silence. However, a pause in conversation is often when people need to think. When conducting research, and just in normal conversations, try to trust the questions you ask and avoid filling the silence after asking.

My experience is that it's very easy to follow a nice open-ended question, such as "How do you feel about it now?" with all sorts of qualifications or assumptions, because silence feels uncomfortable. It can quickly become, "How do you feel about it now?...I guess it must have been hard for you, right?"

So instead of giving someone space to share a thoughtful answer to your open-ended question, all you might get is a "Yes", and perhaps your chance of finding out what they really thought has gone. Instead, have faith in what you ask and stick out the silence.

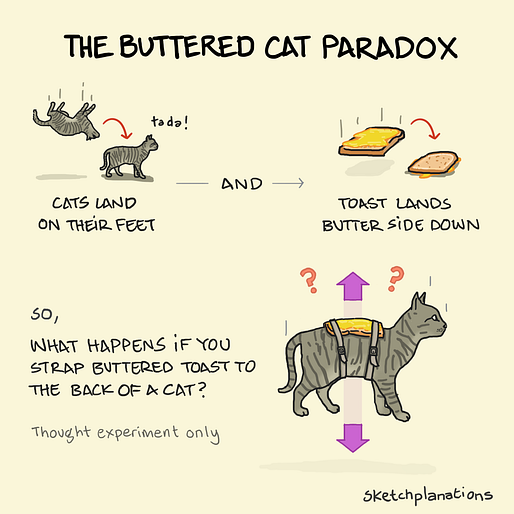

May all your cats and toast land the right way up this week.

Article:

Knowledge Is No Longer Power

An adapted, shortened version of an essay by Rahim Hirji

“Knowledge is power” … until knowledge becomes everywhere.

For centuries, Francis Bacon’s line “knowledge is power” made sense. If you had access to information and others didn’t, you had an advantage.

But in a world where AI can surface answers in seconds, possession of knowledge is no longer scarce. The real advantage has moved upstream and downstream:

• upstream to asking better questions, and

• downstream to turning information into wise action.

A student with a phone can pull up explanations, examples, and model answers instantly. A teacher can generate lesson ideas in moments. The difference is no longer “who knows” but who can judge what matters, what’s trustworthy, what fits this context, and what should happen next.

What still matters: judgement, empathy, and accountability

AI can retrieve, summarise, and pattern-match at speed. What it cannot do in any full human sense is carry the ethical weight of a decision, or the relational responsibility that comes with it.

The original essay uses medicine as a vivid example: AI might detect patterns in scans, but it cannot sit with a scared person, weigh values, and be accountable for the impact of choices.

In education, it’s similar. AI can draft a report comment; it can’t truly know the child, the whānau context, the classroom climate, or the long arc of growth. That’s our work: human, relational, moral.

A whakataukī that fits here:

“He aha te mea nui o te ao? He tāngata, he tāngata, he tāngata.

”What matters most is people.

Power now is the ability to apply knowledge well

Several thinkers mentioned in the essay converge on the same shift: AI reduces the “cost of cognition” (the time and effort required to produce analysis). Karim Lakhani describes how computation reduces cognitive costs, meaning more people can generate outputs that once required expertise.

So what becomes valuable? The essay argues it’s the human capacity to:

• interpret outputs with discernment,

• decide what to try, stop, or scale,

• connect ideas across domains, and

• act with ethics and purpose.

Leaders like Satya Nadella and Reid Hoffman are cited to support the claim that knowledge work is being reshaped, not simply erased: people who can collaborate with AI effectively gain “superagency”, the ability to do more and do it faster, while still steering wisely.

The hidden trap: intellectual atrophy

Here’s the part that matters most for schools.

If AI does the heavy lifting too early, learners can produce work that looks impressive but is brittle. The essay describes students generating well-structured analyses yet struggling to explain or defend them when questioned, leaving “factual confetti” without deep conceptual glue.

That’s the danger: outsourcing thinking instead of augmenting it.

For teaching and learning, this suggests a clear direction: we should design tasks that make thinking visible, and that require students to demonstrate understanding through explanation, application, and reflection.

If the output can be generated easily, then the learning task must move to what’s harder to fake:

• reasoning aloud,

• showing steps and decision points,

• comparing sources,

• applying ideas in new contexts,

• creating with constraints, and

• connecting learning to lived experience.

Ownership and equity: who controls the “new knowledge”?

The essay also flags a power issue: when knowledge becomes algorithmic, who owns the algorithms and sets the rules? Safiya Noble’s work, Algorithms of Oppression, is referenced to argue that search and recommendation systems are not neutral; they can embed bias and shape what people see as “truth.”

For schools, equity is not optional here. If only some learners have:

• reliable access,

• the literacy to evaluate outputs, and

• the coaching to use tools well,

Then the gap widens. The essay highlights the risk of a new divide: not between humans and machines, but between people who have developed the skills to work effectively with machines and those who have not.

From “knowledge acquisition” to “SuperSkills”

The author’s core proposal is the rise of “SuperSkills”: uniquely human meta-capabilities that matter more as AI becomes ubiquitous. These include:

• Big-picture thinking (seeing patterns and connections across fragmented information), • Curiosity (asking questions the tool won’t naturally generate), and

• An augmented mindset (using technology as an extension of human capability, not a replacement).

This aligns with research and commentary on task-based technological change: David Autor is cited to argue that technology tends to replace tasks, not whole roles, and that workers thrive when they learn to do the newly valuable parts of the job.

In schools, that means we should explicitly teach:

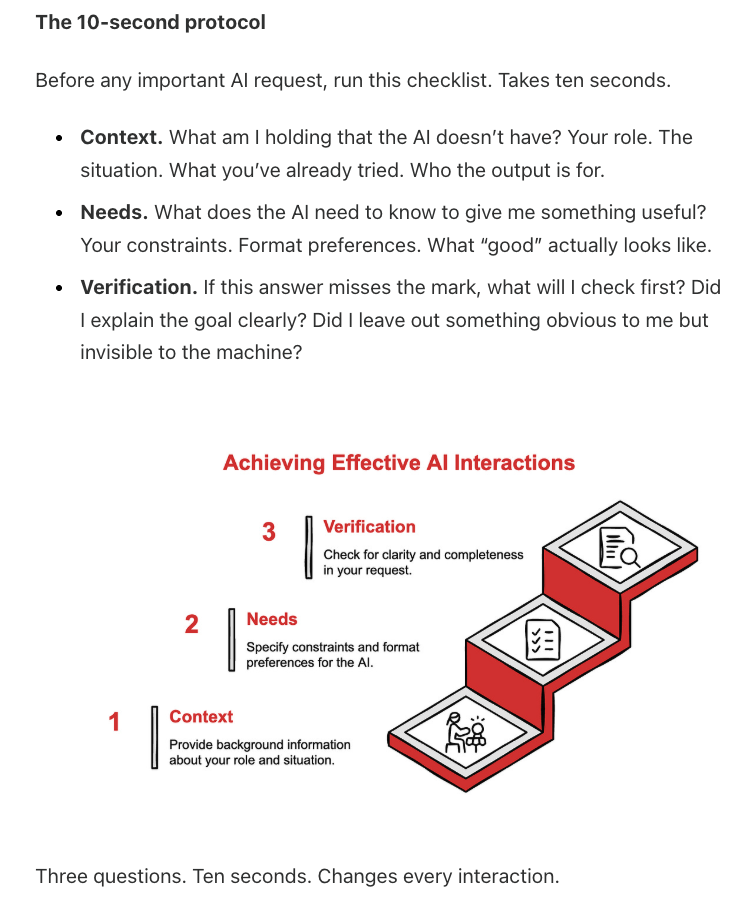

• how to ask strong questions,

• how to check reliability and bias,

• how to use AI drafts as a starting point then improve, critique, and personalise,

• how to cite, explain, and own final decisions, and

• how to keep “human action” at the centre (a nod to Hannah Arendt’s distinction between labour, work, and action).

The bottom line

Knowledge has been democratised. Wisdom has not.

As Nicholas Maxwell puts it, knowledge describes how the world is; wisdom asks how it ought to be.

So the question for teaching is not “How do we stop AI?” but:

How do we grow learners who can use powerful tools without losing their own thinking?

Because the power was never just in knowing. It’s in understanding, choosing, and acting well.

⸻

Further reading mentioned in the original essay

• Algorithms of Oppression (Safiya Noble)

• Work on task-based technological change by David Autor

• Hannah Arendt on labour, work, and action

• Yuval Noah Harari on sense-making in the 21st century

⸻

Next step (one practical move):

In your next writing or inquiry task, add a short “thinking receipt”: What did the tool suggest, what did you accept or reject, and why? That single routine trains judgment, ownership, and integrity in an AI-rich world.

Book Recommendation: