College News

ASC Robotics Team Earns a Spot in RoboCup International 2024

We're thrilled to announce that our very own Year 12 Robotics team, 'Buff Bunny', has earned a prestigious invitation to compete in the RoboCup International 2024 in Eindhoven, Netherlands this July!

All Saints' Robotics Club has a rich history of success, having competed and triumphed in multiple State and National competitions across three divisions. The club's stellar performance has secured its place as a powerhouse in the world-renowned RoboCup, a testament to the dedication, skills, and collaborative spirit of its members.

The Year 12 team – Emma Burton, Kerry Cao, Taryn Lee, Ben Tang and Riley Snook – will be one of 400 teams from 45 countries competing at the highest level.

The global event, known for fostering innovation and excellence in robotics, will host 3,000 participants, with an anticipated 50,000 visitors. Buff Bunny are also the only team representing WA.

Beyond the accolades, All Saints' Robotics Club sees its participation in RoboCup International 2024 as a pivotal opportunity to contribute to the growth of STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) in Australia. By showcasing the skills of their talented members, the club aims to inspire and motivate a new generation of students passionate about STEM fields.

RoboCup is the premier championship for robotics, founded with the aim of sharing knowledge and accelerating developments in robotics. RoboCup also serves as a meeting place for decision-makers and influencers who seek to accelerate necessary innovation in AI and robotics across domains such as healthcare, agriculture, energy, and transportation. The event combines immersive competitions and presentations from organisations aiming to contribute to high-tech solutions for a better society.

The team are currently fundraising to help facilitate this remarkable opportunity. If you would like to help support our team, you can do so by clicking on the button below:

'One Man, Two Guvnors': A College Production to Remember

We extend a heartfelt thank you to those who joined us for the remarkable 2024 College Production, 'One Man, Two Guvnors'. Your presence, energy, and enthusiasm were integral to the success of each show, providing our performers with the encouragement and support they needed to deliver outstanding performances.

As the curtains close on this chapter, we reflect on the countless hours of rehearsal, collaboration, and dedication that went into making 'One Man, Two Guvnors' a resounding success. We are immensely proud of what we have accomplished together and grateful for the opportunity to share our love of theatre with our community.

We look forward to bringing more unforgettable productions to the stage and creating lasting memories for the members of our community.

Neurodiversity Celebration Week

Changing the narrative was the aim of the founder of Neurodiversity Celebration Week, Siena Castellon. As a teenager with ADHD, Dyslexia and Dysgraphia, she wanted to create a more balanced view which focused on strengths and talents of neurodiverse people, alongside acknowledging the challenges.

ASC embraced this mission in our first ever Neurodiversity Celebration Week!

The Wellbeing Council worked with Head of Learning Support, Mr Michael Crawshaw, and Wellbeing Council mentor, Reverend Liz, to create resources and activities promoting awareness and celebrating neurodiverse students and staff. As part of this initiative, our students designed stickers, information sheets, posters and a PowerPoint, alongside a fun Kahoot game for Tutor Groups. There were also lots of fun activities for students to participate in last Wednesday on the Common.

Wellbeing Captain Rebecca Lee and the council did a wonderful job bringing everything together – and the House Council joined in with an icecream fundraiser too! A sunny day, a live band, ice cream, an information table, Year 6s coming to visit, and opportunities to play spike ball or do some chalk drawing led to a real buzz on the Common. Diversity and inclusion were also the Chapel themes for the week. Students were reminded that all people have great value and that all of us are created in God’s image.

Standout highlights included printed personal stories from ASC students and a video interview series featuring staff sharing their journeys with neurodiversity. These stories provided valuable insights into the joys and challenges of neurodiversity.

We look forward to further opportunities in the years to come to raise awareness of neurodiversity, and celebrate all the gifts and strengths neurodiverse people bring to our community.

Reverend Liz Flanigan

Chaplain

Embracing Neurodiversity: Ms McGiveron’s Journey Living with ADHD

In celebration of Neurodiversity Week, we are honoured to feature English Teacher Ms Victoria McGiveron’s article about her experience living with ADHD. With heartfelt honesty, Ms McGiveron gives considerable insight into her personal journey. Her story not only sheds light on the complexities of living with ADHD but also underscores the importance of embracing neurodiversity.

Having ADHD had never occurred to me. All of the ‘markers’ that doctors and teachers (back in the day) screened for didn’t seem to apply to me. The adults and professionals in my life didn’t classify me as existing within the parameters, which consisted of strangely specific statements like, ‘Is your child so energetic that they seem as if they are driven by a motor?’, ‘Does your child make careless decisions?’, or ‘Is your child forgetful?’ They didn’t see me as mercurial, or excitable, or impulsive. Don’t get me wrong; I was all of these things, and so are lots of children. But they don’t have ADHD.

I got my diagnosis as an adult, and it changed my life. Suddenly, everything just sort of clicked into place. I am the way that I am, not because I’m a nihilistic fiend, but because I have Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder. This was groundbreaking for me, because it didn’t even cross my mind as a possibility until my best friend, Ki, got diagnosed. I remember opening the Snap that she sent me on the Tuesday after her 24th birthday, just after her diagnosis; ‘Vic,’ she said, the relief clear in her voice, ‘it all makes so much sense now.’ We had very similar experiences and traits, so she said that I should get tested as well. A few months later, a Psych in West Perth confirmed that I have – quite severe, apparently ADHD.

It turns out that ADHD can present very differently in females than in males. It also turns out that the majority of the indicators of ADHD are those seen most often in males, so it’s relatively common for females to get misdiagnosed, or just slip through the cracks al together. Especially if no one’s really looking for it - if it’s not in your family and there aren’t any major red flags that would get doctors or teachers to question what’s going on.

I was born in a little town on the border of Wales, called Mold - population 10,000. I went to a private school in an English city called Chester. It was strict; old-school. Quintessentially ‘British’. As a girl, I was told that manners are everything: to speak when spoken to, and to sit still. I managed to repress the need to stim or fidget for years because of the memory of Mrs. Hughes shouting, ‘For heaven’s sake, sit still Victoria!’ at me, her voice reverberating around the room. Having the urge to fidget being repressed, objectively, doesn’t sound like a big deal. However, it didn’t make me more engaged with learning or able to focus more readily. It just meant that all of the energy that could have been slowly being released through little and fast movements through fidgeting was stuck in my head. It felt like marbles were rattling around in my brain. They were noisy and clattering against each other, and really distracting.

Looking back, I can definitely see the signs. I struggled to follow instructions, to wait my turn. I couldn’t stop myself from speaking, even if I interrupted others. I became disproportionately angry if I perceived an injustice, amongst other markers. It got worse as I got older. In high school, the massive bursts of energy could no longer be satisfied with ballet or horse riding or tennis; I started going on nightly 5-10km runs right before bed. If I didn’t, I wouldn’t be able to sit still, or focus or function. I began lashing out at my family; I would become visibly irritated or explosively angry; I’d get mean and snarky. After the fact, I’d sit there and feel racked with guilt – why did I do that? As I progressed further into high school, more symptoms began to appear. I’d get what I know now as ‘sensory overload’. I remember sitting in Modern History, my teacher trying to teach us about the global implications of the Treaty of Versailles. I sat there, trying to listen, but really I was just watching the clock. I could feel my thick school summer dress sticking to the backs of my thighs, my phone and cash and chapstick sticking into my leg - I had shoved it into the too-small dress pocket. My ponytail was pulling on my hairline and giving me a headache. I really needed to cough and drink water, but I didn’t want to annoy the teacher even more than I had already by being so woefully disengaged.

I felt like I had no control over myself. I had no ability to verbalise these feelings. Looking back, the switch is clear; I can chronicle when symptoms worsened and can connect the causality. But at the time, I didn’t have the self-awareness or objective understanding to consider my experience. It was just my reality. My Mum, doing her best and in no way equipped to deal with the absolute menace that I was, would, in a moment of weakness, demand, ‘What’s wrong with you?’. ‘I don’t know,’ I’d say. I wish I did. I didn’t know why I couldn’t make myself study, or do my homework, or follow instructions, or operate with any form of executive function.

Luckily, without sounding pretentious, I was always quite clever. My parents prioritised instilling a love of reading in me at a young age and, honestly, I lived off my knowledge learned through reading for far too long in the place of actual homework or study. Also luckily, my ADHD brain thrives on time pressure. The joke was always ‘pressure makes diamonds’. And for me, it did. Seriously, it was crazy what I could achieve with a deadline and high stakes.

I had supportive parents, and was able to figure out how to live with my (at the time, undiagnosed) ADHD. But life was hard. I’ve always found explaining what ADHD is like to a neurotypical person is a fruitless endeavour. If I broke my arm, it would be easy to verbalise the experience; having a broken arm is not the norm, so there’s a baseline; a basis for comparison. ‘Normally your arm feels like ______, and now it feels like _______.’

But I don’t have a comparison with this – ADHD is my reality. I know that the way that I function isn’t normal, because things that I find impossible others do with relative ease. That’s not to say that being organised is effortless for others; but things like being organised and sitting still and not interrupting conversations are societal expectations which most neurotypical people are able to meet. Authority figures become upset, angry even, when you don’t adhere to them. It’s seen as a natural learning curve; something that’s challenging initially, but with routine and exposure, you were supposed to get used to it and develop the skills. But it never happened for me. This made high school difficult.

I’d go to Chemistry, rush to my desk, slam my books down and manically ask Bec if she was also incredibly stressed about the upcoming assessment. ‘You haven’t started studying, right?’, I’d ask pleadingly; seeking the validation that I’m not the problem and that no one had studied and that everything would be all right. Of course, this never happened. Bec would calmly, and as casually as possible so as not to freak me out even more, reply that she’d dedicated the previous weekend to studying key concepts, and had gotten through a couple of practice quizzes. When this far-too-regular interaction happened, I’d inevitably spiral for a moment. Then the adrenaline would kick in, I’d be terrified that this was it – I’d fail Chemistry and fail every subject, and my parents would finally ship me off to the Swiss boarding school that they kept talking about in hushed tones when they thought I couldn’t hear. Then and there, I’d create a plan of action: the new me. Right, I’d think, tonight will be the dawn of a new era. I’m going to get my head into gear. I’m going to study as soon as I get in. I’m not even going to get a snack or change out of my uniform. I’m just going to sit myself down and study all night.

Why don’t you begin now? Bec would ask. ‘Let’s go through this practice test together.’ I’d agree wholeheartedly, sincerely wanting to do better; to be better. I would open the booklet and try to get on with the work. But then, I’d notice how annoying it was that my school dress restricted the range of movement in my shoulders. Other students would be talking. I tried to shut them out, to lock-in to my work. I would become aware of how clunky my school shoes felt. How warm it was at my desk. How scratchy my pen was as it balanced chemical equations – where was my smooth pen that I liked to write with? I’d drink water and it was too cold. I’d suddenly feel trapped, not able to think about anything other than how uncomfortable I was. I didn’t ever stop to consider whether this was normal.

Most of the rhetoric that I hear about ADHD is irrelevant to me and, honestly, sort of condescending; dismissive. I can’t count the number of times that I’ve heard that ‘it’s a superpower’.

ADHD is not a superpower. ADHD is a genetic neurodevelopmental disorder, where the brain grows differently, lacking action from dopamine and norepinephrine, the chemicals involved in pleasure and reward. Operating with a decreased ability to stimulate these chemicals means that people with ADHD actively search for situations where these chemicals could be released, which is why we can experience inattentiveness, hyperactivity and impulsivity.

What does that feel like for a teenager? First, we need to examine how a neurotypical teenage brain functions.

Adolescence marks change in many respects; one of the most significant is the experience of complex emotions. However, factors like rising hormone levels compromise teenagers’ ability to handle these feelings. Studies show that the brain’s ability to process emotions is dependent upon the developmental stage of the brain. During puberty, these studies suggest, there is a shift from reliance on the limbic system to the prefrontal cortex. The limbic system, a structure underneath the cerebral cortex and above the brainstem, is the part of the brain involved in our behavioural and emotional responses, primarily processing and regulating emotions. The prefrontal cortex is grey matter that occupies portions of all three surfaces of the frontal lobe. Humans’ highly developed prefrontal cortices are one of the factors that makes us different from other animals. It’s often referred to as the ‘personality centre’ of the brain, because how information is processed there directly impacts our behaviour. The prefrontal cortex is where we process moment-to-moment input from our surroundings, compare that input to past experiences, and then react to them.

The adolescent brain, however, differs significantly from both younger children and adults. It undergoes extensive remodelling; some areas develop connections while others are pruned. Synaptic pruning is the process where your brain eliminates the neurons and synapses that aren’t used often. The fact that the limbic system, the emotional centre, matures quickly and the prefrontal cortex lags, results in teenagers feeling the full weight of their new complex emotions’ limited capacity to regulate or process them. This means teenagers often feel emotions strongly without as much ability to control them; they, seemingly overnight, stop being their measured and reasonable pre-pubescent selves and become quick to react. To reiterate, the area responsible for skills like planning, prioritising, and making good decisions is not developed fully until well within your 20s.

So, what does this have to do with ADHD? Studies have found that ADHD is associated with weaker function and structure of the prefrontal cortex, which in adolescence is dubious to begin with. Remember that the prefrontal cortex, which is where the ADHD brain is weaker, plays a crucial role in regulating things like attention span, behaviour and emotional regulation.

A neurotypical teenager will find it difficult to regulate their behaviour and emotions because of their stage of brain development. A neurodiverse teenager with ADHD will find it near impossible because of the way their brain just is, on top of the development nuances.

The point of all of this is not to say that I’m advocating for students with ADHD to get a free pass in high school. It’s the opposite, actually; they need help. The only way that I can function is with a strict routine. At any given time between Monday to Friday, I have every hour accounted for. That routine is printed out and clearly displayed in my office at home, on the G Drive on my laptop, and is a pinned note in my phone. That way, I don’t have to rely on trusting my brain to remember things or to stay on track – all I have to do is follow the routine. I know that, for some people, this sounds crazy. And it’s only a small element of the strategies I’ve implemented over the years to make life as functional and consistent as possible. It’s not all bad; there are bits that are actually very good. Still, I don’t like to use those words ‘bad’ or ‘good’. I don’t think that your neurodivergence should be moralised. It’s not actually ‘good’ or ‘bad’ - it just is.

Exploring French Cinema: ASC Students Attend the French Film Festival

On March 14 students of French from Years 10–12 attended the French Film Festival at the Palace Raine Square Cinema, organised by the Alliance Française de Perth. The excursion served as a dynamic extension of classroom learning and provided students with a unique opportunity to immerse themselves in the francophone world of the movie Princes of the Desert.

With its rich cinematography and a compelling storyline, this cinematic journey not only transported students to the spectacular landscapes of Morocco but also offered a nuanced perspective on the French culture and history.

Throughout the viewing, students not only enjoyed the film with their friends but also gained a deeper appreciation of how French cinema directly connects to and complements their French curriculum.

Jing Quan Chong (Year 12) shared his experience: “The film was an immersive experience in the French language as well as the culture of French-speaking Morocco – I thoroughly enjoyed this film as a result.”

Madison Kent (Year 10) also shared her experience: “I really enjoyed watching the French film as it allowed me to test my listening skills and be immersed in French conversations, all while enjoying a great story!”.

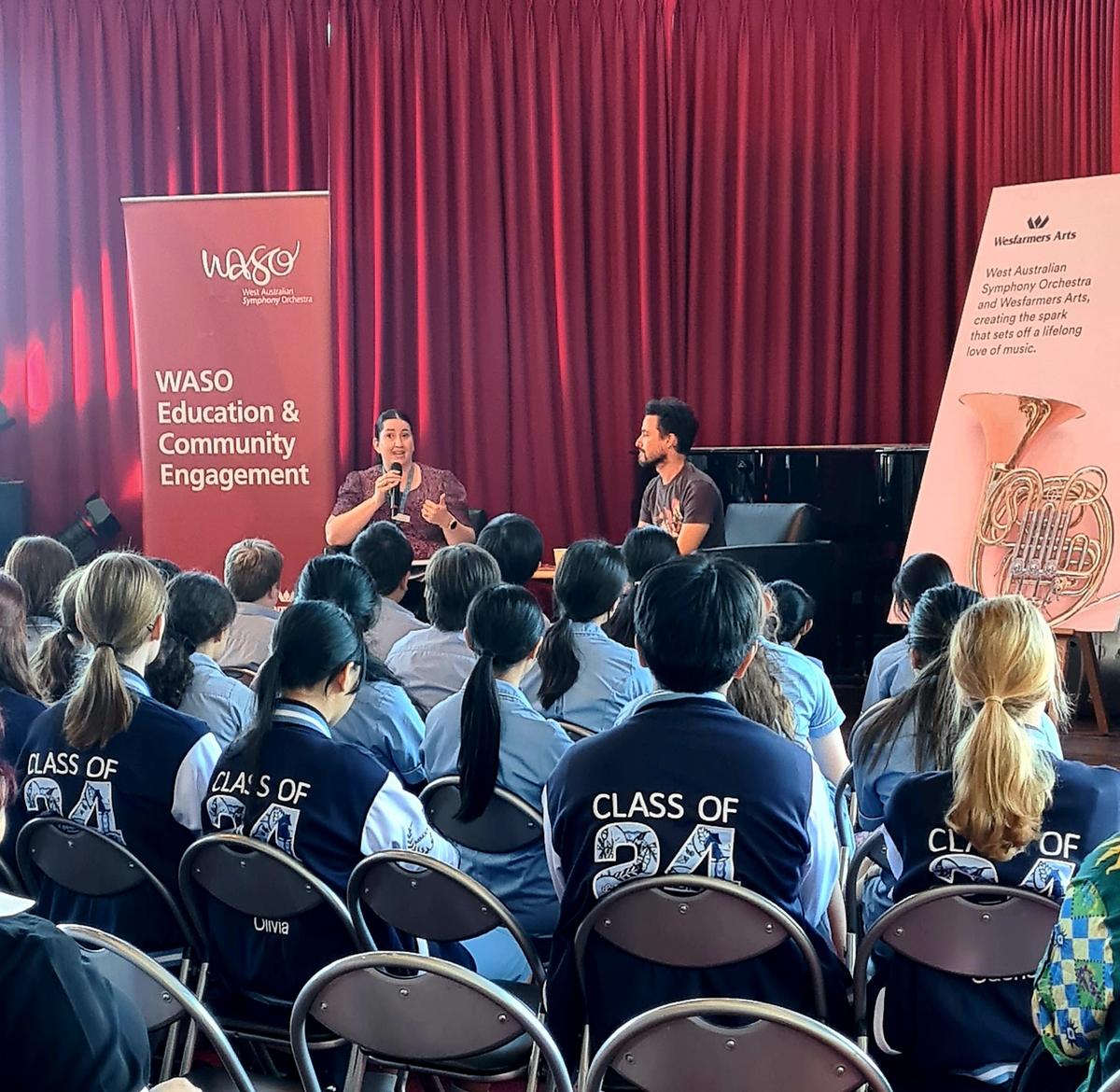

WASO Morning Symphony Excursion

Our talented string ensembles recently had an unforgettable experience at the WASO Morning Symphony excursion. They were treated to a behind-the-scenes look at the West Australian Symphony Orchestra's rehearsal of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 4, conducted by the renowned international conductor Mr. Asher Fisch. This provided them with a rare glimpse into the intricate workings of a professional orchestra, witnessing firsthand the commitment and precision required to bring such a masterpiece to life.

Our students also had the opportunity to engage in a Q&A session with a WASO cellist, Mr Nick Metcalfe. They delved into what it’s truly like to be a part of such a prestigious ensemble, learning about the dedication, discipline and passion required to play at the highest level. From discussing the rigorous audition process to understanding the daily life of a professional musician, our students gained valuable insights into the world of orchestral performance.

Years 10 and 11 Mock Trials

Year 10 and 11 students recently participated in Mock Trials. The event, designed to simulate real courtroom proceedings, saw students passionately advocate for their respective cases. They were given a mock legal case and had to prepare legal arguments, competing against other schools in real courtrooms.

The two All Saints' teams competed against Rossmoyne SHS, with one team victorious and the other narrowly missing out on the top spot.

The Mock Trials not only provided students with an immersive learning experience in the field of law but also fostered teamwork, analytical thinking and public speaking skills.

Congratulations to all the participants for their outstanding performance.