Deputy Principal News: Raising Resilient Problem Solvers

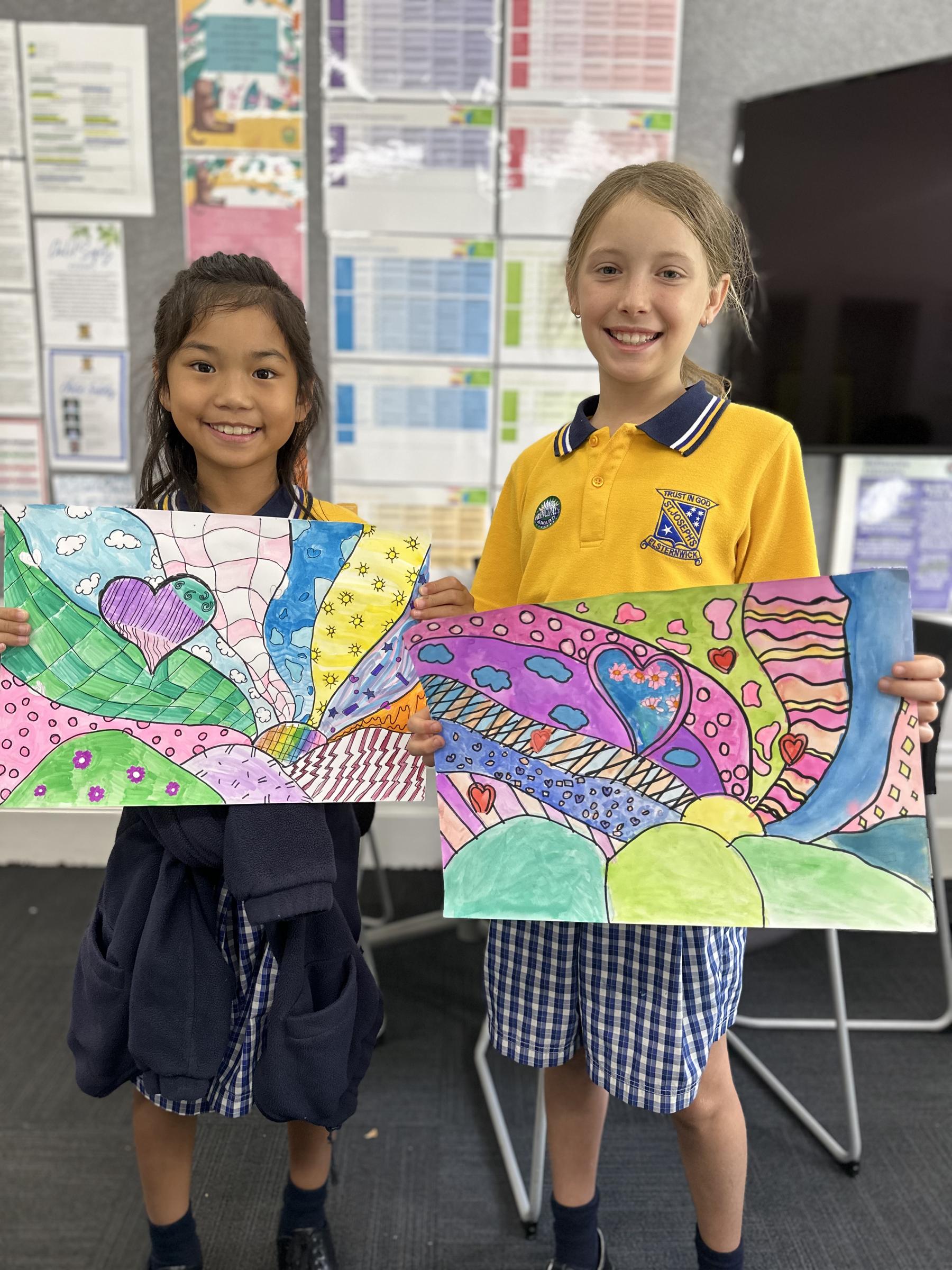

It has been so heart-warming to walk around our school and see so many calm and orderly classrooms, where students are engaging positively with their learning, their teachers and their peers. This is a testament to our whole school approach to teaching and learning as we prioritise 'Relationships and Rigour' in our day to day interactions with the children.

While we can see settled students in our highly structured classroom environments, we can see some students become a little 'lost' as they enter the playground. The playground environment asks students to show great resilience, flexibility and problem solving skills as they navigate play with their peers.

Moving from the calm of the classroom into the excitement of the playground is the highlight of some students' day, however, this transition can cause angst for some. Navigating these changes can be difficult. Negotiating play, resolving conflict, asking a friend to play - these are all essential social skills that need to be explicitly taught and require consistent practice and unpacking with children. Add to this the ever changing landscape of who may at school on any given day and who may be tucked up in bed at home sick, as well as the idea that although students agreed to play down ball, the plans have changed to a game of footy! Put simply, it’s a lot for our children to navigate and constantly adjust and readjust to - and it is resilience and problem solving that are at the centre of helping students to overcome these challenges.

At St Joseph’s, we have always prioritised our students’ wellbeing. We understand the importance of social and emotional learning and explicitly teaching these essential wellbeing and friendship skills - how to ask to play, how to negotiate what game to play, how to respond to change or things that don’t go our way, how to problem solve, how to resolve conflict with peers and how to ask for help when required.

As children develop and grow, and as their friendships change and evolve, they require ongoing support in these areas of their lives. Through our whole school Berry Street curriculum and our strong focus on relationships and wellbeing (Rights, Resilience & Respectful Relationships), we are constantly striving to ensure students feel supported and equipped for success in their lives; building students' independence and resilience and developing their problem solving skills. We know that our partnership with home is essential to this success. Being a good role model, being open to discussion, modelling positive self-talk and coaching children through problems, can all help our children to continue to thrive both emotionally and socially in this environment.

Below is an article on the importance of resilience and problem solving by Michael Grose, founder of the Happy Families website, who is one of Australia’s leading parenting educators.

As always, if you have any concerns or would like to discuss your child’s wellbeing, please don’t hesitate to reach out.

Alannah Harrison

Deputy Principal

Raising Resilient Problem Solvers

By Michael Grose

Personal problem-solving is an under-rated skill shared by resilient children and adults. First, identified alongside independence, social connection and optimism by early resilience-researchers in the US, the ability to solve your own problems is the basis of a child’s autonomy and self-efficacy.

When parents solve all children’s problems we not only increase their dependency on adults, we also teach kids to be afraid of making mistakes and to blame themselves for not being good enough. As I noted in my book Anxious Kids, this is fertile ground for anxiousness and depressive illness.

So how can we raise kids to be courageous problem-solvers rather than self-critical, low risk-takers? Here are six practical ideas to get you started:

Turn requests for help into problems for kids to solve

Kids get used to bringing their problems to parents to solve. If you keep solving them, they’ll keep bringing them. “Mum, Sarah’s annoying me” “Dad, can you ask my teacher to pick me for the team?” “Hey, I can’t find my socks!” It’s tempting if you are in a time-poor family to simply jump in and help kids out. Alternatively, you can take a problem-solving approach, cuing them to resolve their own problems and take responsibility for their concerns. “What can you do to make her stop annoying you?” “What’s the best approach to take with your teacher?” “Socks, smocks! Where might they be?”

Ask good questions to prompt problem-solving

A problem-solving approach relies on asking good questions, which can be challenging if you are used to solving your child’s problems. The first question when a child brings you a problem should be: “Can you handle this on your own?” Next should be, “What do you want me to do to help you solve the problem?” These questions are not meant to deter children from coming to you. Rather to encourage and teach them to start working through their own concerns themselves.

Coach them through problems and concerns

Imagine your child feels they were unfairly left out of a school sports team by a teacher and asks you get involved. The easiest solution may be to meet with the teacher and find out what’s going on. You may or may not resolve the problem but in doing so you are teaching a child to become dependent on you. Alternatively, you could coach your child to speak to the teacher themself and find out why they were left out. Obviously, there are times when children need their parents to be advocates for them such as when they are being bullied, but we need to make the most of the opportunities for children to speak for themselves. Better to help your children find the right words to use and discuss the best way to approach another person when they have problems. These are great skills to take into adulthood.

Prepare kids for problems and contingencies

You may coach your child to be independent – walk to school, spend some time alone at home (when old enough), catch a train with friends – but do they know what to do in an emergency? What happens if they come home after school and the house is locked? Who do they go to? Discuss different scenarios with children whenever they enter new or potentially risky situations so that they won’t fall apart when things don’t go their way. Remember, the Boy Scouts motto – "Be Prepared!"

Show a little faith

Sometimes you’ve got to show faith in children. We can easily trip them up with our negative expectations such as saying “Don’t spill it!” to a child who is carrying a glass filled with water. Of course, your child doesn’t want to spill it but you’ve just conveyed your expectations with that statement. We need to be careful that we don’t sabotage children’s efforts to be independent problem-solvers with comments such as, “Now don’t stuff it up!”, “You’ll be okay, won’t you?”, “You’re not very good at looking after yourself!”

Applaud mistakes

Would a child who accidentally breaks a plate in your family while emptying the dishwasher be met with a ‘that’s really annoying, you can be clumsy sometimes’ response or a ‘it doesn’t matter, thanks for your help’ type of response? Hopefully it won’t be the first response, because nothing shuts down a child’s natural tendencies to extend themselves quicker than an adult who can’t abide mistakes. If you have a low risk-taking, perfectionist child, consider throwing a little party rather than making a fuss when they make errors so they can learn that mistakes don’t reflect on them personally, and that the sun will still shine even if they break a plate, tell a joke that falls flat or doesn’t get a perfect exam score.

As I’ve often said, your job as a parent is to make yourself redundant (which is different to being irrelevant) at the earliest possible age. The ability to sort and solve your own problems, rather than step back and expect others to resolve them, is usually developed in childhood. With repetition and practice problem-solving becomes a valuable life-pattern, to be used in the workplace, in the community and in family relationships.

By Michael Grose

Parenting Ideas