Just A Thought:

On Trying And Failing As A Youth Sports Parent:

by CHRIS CILLIZZA

On Saturday night, I found myself in a familiar place: Sitting in cramped bleachers watching my 10-year-old play basketball.

Both of my boys are very into sports — football for the older, basketball and baseball for the younger — so most of my weekends (and weekdays, if I am being honest) are spent on some sideline or another.

This should be a joyous experience. Having healthy kids who are able to participate in any sort of athletics is, on its face, a remarkable thing. With all the bad in the world, the chance for my kids to go out and compete — and have fun — is the rarest of treasures.

Notice I said “should” in the paragraph above. Because, for me, it often isn’t. No matter how much self-talk I do beforehand about this being a learning experience and for fun, everything changes when the whistle blows.

Suddenly, it feels to me like this all matters A LOT. I am laser-focused on every little thing my kid does. When he makes a shot, I feel joy. When he messes something up, I am angry. Like, really angry.

Judging from a quick look around the stands — or the sidelines — I am far from the only one who is way too invested in how my kid is doing on the court or the field. I have personally witnessed verbal (and almost physical altercations) between parents of opposing teams. I have seen — innumerable times — a parent screaming at their kid to do better....or else. Or at the coach to play their kid more or at a different position or, well, something.

I think it’s beyond debate then that parents are ruining youth sports. The question is why.

Having spent a lot of time thinking about this, I’ve come to this conclusion: It’s because we, as parents, have massively unrealistic expectations about how far our kids will go in sports.

I think the worst thing for a parent is to have a kid who shows some early promise in a sport. Maybe they are a little more coordinated with their feet than their peers. Or they can throw a baseball harder. Or they pick up skating faster than anyone else their age.

That spark of ability — no matter how small — sprouts a seed in parents. That seed says, “Hey, my kid is special! We may have something here!” And it is both addictive and corrosive.

We all want our kids to excel and succeed. All the better if they can do so in sports, which holds a special and vaunted place societally. To produce a great athlete is conflated as a reflection of you as a parent. I did this! My kid is great, at least in part, because of me! Reflected glory and all that.

But what we fail to grasp — consciously or unconsciously — is how incredibly long the odds are that your kid will be good enough to play a sport in college, much less beyond that.

The simple fact is that the VAST majority of young athletes won’t play a sport in college. And, if they do, the VAST majority of them will not make a living playing a sport.

But it doesn’t seem that way when little Johnny hits a home run when he’s nine against a 12-year-old pitcher. Or makes three straight 3 pointers in a game. All of a sudden, in the words of Kevin Garnett, anything is possible. And parents quickly lose all sense of perspective.

With all that said, I don’t think all of the blame lies on parents. (Most but not all.)

Over the past 30 years or so, youth sports have become professionalised in a way they were not prior. Now, there are travel teams galore for every sport. Those teams travel all over the country from the time the kids are 10 or 11. And they all are aimed at projecting a single message: Your kid is going places.

Why? Because that’s where the money is. Parents, as I said above, look at

their kid and see a future professional. So what better way to separate parents from their money than to cater to that belief — whether it’s based in reality or not?

Little Timmy might be a pro if he just did that one more session of hitting with me or signed up for my summer camp. And the flipside is also true: If you don’t sign Timmy up for that hitting clinic or that camp, you are robbing him of his very legitimate chance at becoming a star.

Every little decision feels magnified — as if what you choose in that moment will determine your child’s level of athletic success for his or her entire life.

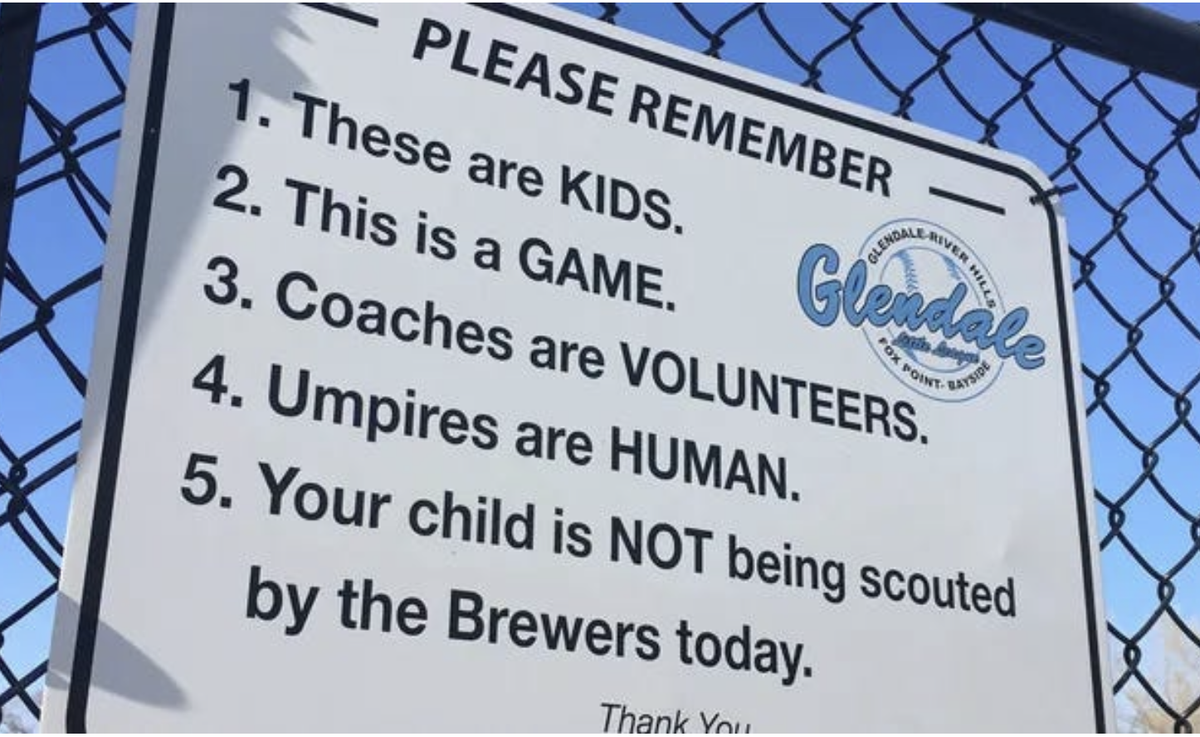

Which is ironic. Because if you talk to anyone who has actually been a college or pro athlete, to a person, they will emphasize that it is a marathon, not a sprint. This sign, a version of which I saw posted at a Little League field in Loudoun County, Virginia, gets at that idea:

No one at bat or one game, or even one season matters all that much when you are 12 years old. It’s about the cumulative effect. Do you keep getting better, or do you plateau? As the competition improves, can you level up as well? How much of your time and energy are you willing to put in to get better? Does your body allow you to keep playing?

The reality is that the youth sports culture is all screwed up. We have no perspective. We lack context. We are uniquely focused on the here and now.

The funny thing is that the answer to our problems is right in front of us: It’s in our kids.

My boys get upset when they lose. Or if they don’t do as well as they had hoped to. They also get over it pretty darn quickly. Tears turn to smiles and laughter within minutes. A tough basketball loss can be cured by a treat from McDonald’s.

In short, our kids don’t take any one game too seriously. They know there will be another chance — and likely, LOTS more chances. In the grand scheme of things, a strikeout is just a strikeout. It’s not a character judgment.

Plus, they aren’t on teams solely to begin their (extremely unlikely) ascent to the ranks of the pros. They like the camaraderie that comes with being on a team. They like the jerseys. And the shoes. And all of the things WE liked when we were kids too.

The world is forever trying to rush our kids to grow up fast. Sports is no different. But, ask any adult, and they will tell you they would give anything to go back to being a kid again.

I am going to try and remember that when my son takes the mound to pitch the next time. Or when he throws up an airball on an ill-advised shot. Or when he turns the ball over, and the other team puts it in the back of the net.

Our kids are watching us and learning from what we do. And right now, I fear we are failing them.