Assistant Principal - Pastoral Care

Becoming a Stronger Learner

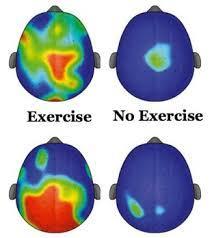

A considerable amount of research is coming out at the moment saying that exercise is critical to maximising our brain potential. For many years I have noticed that students who are widely involved in extra-curricular activities also often achieve strong academic results. I previously theorised that this was because they were people who learned to be efficient, were goal orientated and tended to be self-disciplined. The latest research may be challenging this theory or at least adding extra dimensions to that theory. Exercise, it seems, stimulates key areas of the brain that drive memory and learning. Worldwide interest in this research has occurred due to the rising life expectancy in Western society and thus the rise also in dementia.

The most important conclusion that we can derive from this research is that regular exercise is important for the brain. In our increasingly sedentary culture this may create challenges for some. If your child is not involved in sport or doing physical activity on a regular basis, then you need to get them moving. Most simply it might be a regular, hard walk or a bike ride. If they are not doing regular exercise they will be limiting the ability of their brain to function optimally. We know that participating in groups or teams further stimulates positive chemicals and motivates us to keep going or participating.

Of course there is no one thing that makes us a stronger learner – it is a range of activities and dispositions that are essential for us to grow and develop. Just exercising will not magically result in us becoming a strong learner but it is a key element that can enhance our learning.

I have included below a blog post that explains some of the more technical elements regarding this theory and why exercise benefits our learning. Of course the advice is pertinent for all of us no matter what our age.

Heidi Godman, Executive Editor, Harvard Health Letter

There are plenty of good reasons to be physically active. Big ones include reducing the odds of developing heart disease, stroke, and diabetes. Maybe you want to lose weight, lower your blood pressure, prevent depression, or just look better. Here’s another one, which especially applies to those of us (including me) experiencing the brain fog that comes with age: exercise changes the brain in ways that protect memory and thinking skills.

In a study done at the University of British Columbia, researchers found that regular aerobic exercise, the kind that gets your heart and your sweat glands pumping, appears to boost the size of the hippocampus, the brain area involved in verbal memory and learning. Resistance training, balance and muscle toning exercises did not have the same results.

Exercise and the brain

Exercise helps memory and thinking through both direct and indirect means. The benefits of exercise come directly from its ability to reduce insulin resistance, reduce inflammation, and stimulate the release of growth factors—chemicals in the brain that affect the health of brain cells, the growth of new blood vessels in the brain, and even the abundance and survival of new brain cells.

Indirectly, exercise improves mood and sleep, and reduces stress and anxiety. Problems in these areas frequently cause or contribute to cognitive impairment.

Many studies have suggested that the parts of the brain that control thinking and memory (the prefrontal cortex and medial temporal cortex) have greater volume in people who exercise versus people who don’t. “Even more exciting is the finding that engaging in a program of regular exercise of moderate intensity over six months or a year is associated with an increase in the volume of selected brain regions,” says Dr. Scott McGinnis, a neurologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and an instructor in neurology at Harvard Medical School.

Put it to the test

So what should you do? Start exercising! We don’t know exactly which exercise is best. Almost all of the research has looked at walking, including the latest study. “It’s likely that other forms of aerobic exercise that get your heart pumping might yield similar benefits,” says Dr. McGinnis.

How much exercise is required to improve memory? These study participants walked briskly for one hour, twice a week. That’s 120 minutes of moderate intensity exercise a week. Standard recommendations advise half an hour of moderate physical activity most days of the week, or 150 minutes a week. If that seems daunting, start with a few minutes a day, and increase the amount you exercise by five or 10 minutes every week until you reach your goal.

If you don’t want to walk, consider other moderate-intensity exercises, such as swimming, stair climbing, tennis, squash, or dancing. Don’t forget that household activities can count as well, such as intense floor mopping, raking leaves, or anything that gets your heart pumping so much that you break out in a light sweat.

Mr Mick Larkin - Assistant Principal - Pastoral Care