Teaching & Learning

by Daniel Symons, Years 11 & 12 Coordinator

Over the first few days of being at Preshil, I overheard ongoing discussion about how the cleaners had arranged the Blackhall classrooms in teachers’ absence. Preshil stalwarts murmured with disdain at the neat rows of tables, all facing the front.

Despite practices in some schools, education has long abandoned a singular model of classroom performance as teacher-centric, lecture-style content delivery. While there is a time and a place for this tradition, it evokes a system much closer to ‘information delivery’ rather than teaching and learning, characterising teachers as information sources and students as passive receptacles. Even more problematic is the naïve assumption that ‘expert’ knowledge is impervious to examination, interrogation or development.

This is not our ‘way’ at Preshil.

Our tradition is one that recognises the value that individuals bring to the learning experience. We understand that if our practice fails to recognise the power of the learner, then any outcome will be facile, fractious or simply ignored. Michel Foucault was a powerful sceptic of power imbalance in schools, discussing the ways that teachers often seek to exert ‘power over’ students, rather than harnessing the power that exists within the communitarian chemistry of connectedness. Margaret Lyttle was a pioneer of this approach long before differentiation became an educational trend, asserting that learning is “a group effort for and by the group, at the interest level of the group, and it is not some activity or task imposed from above by some adult” (The Courage Document, 2010, p19).

Preshil teachers understand that physical spaces must reflect a student-centred ethos. As David Thornburg puts it in his seminal work on learning spaces, From the Campfire to the Holodeck (2014), “physical environments that impede learning hurt teachers as well as students” (p2). Thornburg recognises that the physicality of teacher-centred spaces, reflecting Industrial Era educational values, is dysfunctional for effective learning; he dubs this ‘dysfacilitia’. As a progressive alternative, Thornburg suggests the model of learning spaces as ‘campfires’, ‘watering holes’ and ‘caves’ to facilitate pedagogies of storytelling, discourse and individual ‘flow’, respectively.

Considering this, I’ve put together a little collection of progressive Preshil pedagogical practice of ‘place’. This is not representative of every progressive use of space, just a brief assembly of experiences that I have been privy to over the past week. The fact that I was so easily able to find examples reflects the ubiquity of this kind of approach in our learning community.

Last Friday I took my Year 12 Higher Level Language and Literature students to a nearby café to evoke the Bachelor of Arts experience of good coffee and discursive collaboration (please excuse my ham-fisted selfie skills). A parent, Michael Quinn, articulated the mood so eloquently: “Espresso, Gitanes, berets, baguettes and repetitive syntactic, structure at dawn. Groovy.” This learning space blended the ‘watering hole’ and ‘cave’ learning spaces, allowing us to find a balance between discourse and independent learning as needed.

In the photo above, taken by the magnificent John Collins, Chris McDuff facilitates a learning experience employing both ‘campfire’ and ‘cave’ learning spaces. In an empowerment of student agency, learners have self-selected to work in small groups or individually on the required task. Chris is able to circulate through the different spaces to provide individualised help where needed.

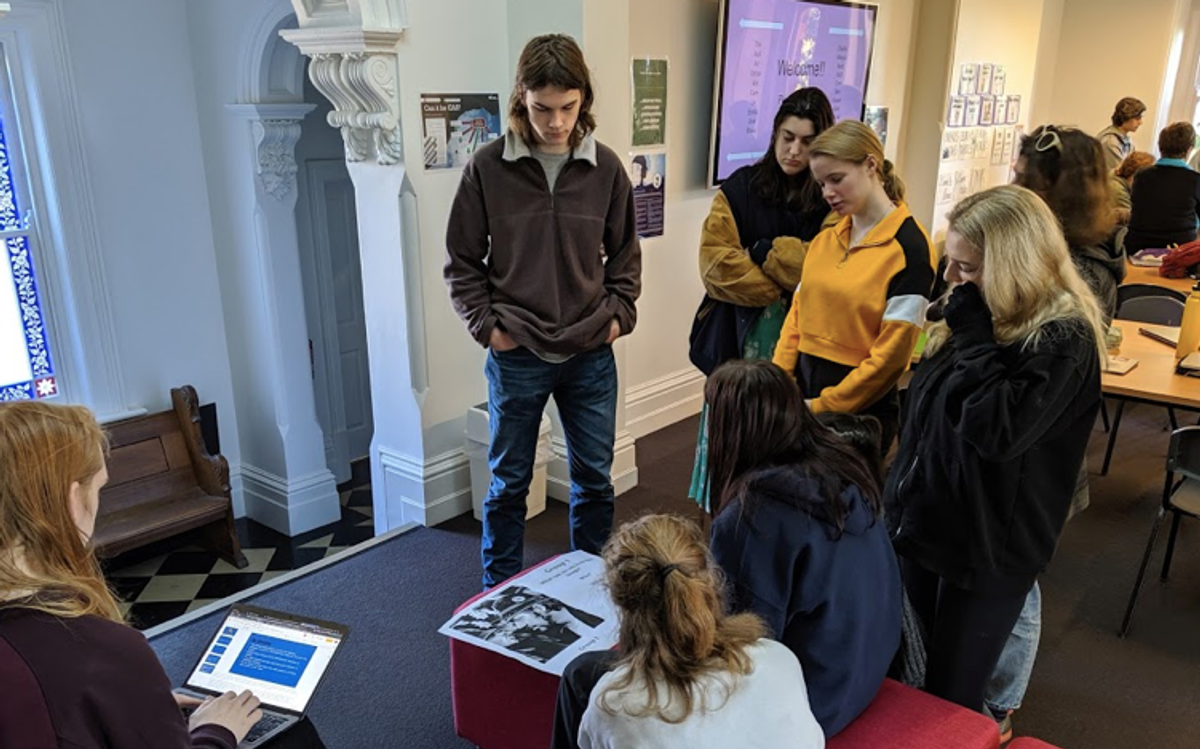

The two images following were taken from a Theory of Knowledge class that I found deeply impressive. Linda Kay designed a series of student-centred learning experiences exploring the creation, distribution and evaluation of knowledge in the Arts.

This group of students took the opportunity to design a learning experience for the whole class, rather than deliver their material as a presentation. They shaped the classroom to facilitate ‘campfire’ and ‘watering hole’ learning spaces, drawing on the culture of progressive learning spaces they have had modelled to them in their time at Preshil. This experience showed me how the student-centred ethos has resonated within the culture of our School through its history. I felt the smiling spirit of Margaret Lyttle.

The last embodiment I was able to capture is our famously celebrated Philosophy guru, Dr Lenny Robinson-McCarthy, conjuring a ‘campfire’ with her Year 12 Philosophy students: the group gathers around to hear a master storyteller weave the narrative of a particular thinker’s work. After revelling in this experience, students are asked to personalise their understanding by reflecting individually in their respective ‘caves’.

A healthy scepticism is necessary when reading the marketing material of any organisation; indeed, we actively teach this approach through English and Media analysis skills. At Preshil, however, I am proud to say that our publicised ethos matches our everyday practice: we live into our values of courage, innovation and respect for student agency and these values are manifest in diverse learning spaces and their use.