Parallel - Student News

From the Editors

Hi everyone and welcome to the sixth issue of Parallel for this year! We have some very insightful and perceptive articles in this issue for you to explore and engage with. As always, we welcome your feedback and suggestions about what could be better.

We have decided to open a new advice column for the newspaper called “HELEN HELP ME!” It will involve our mysterious Helen, who will be able to offer help about problems faced by students in a (somewhat humorous) way. To list a problem, please complete the form here: https://goo.gl/forms/FqMRuvqGfrRvgc162

Happy reading all!

Leo and Jordan

Editors-in-Chief

SRC News

Hey everyone! To start off Term 2, we've got some updates for you all on our current and upcoming projects as well as goals for the near future.

Last term the SRC sent out a survey to all students to get an idea of their thoughts on the current sports uniform policy. It was evident from the overwhelming number of responses (400+) that the large majority of students would like a change. From the survey results it was found that 91% of students have been discouraged from participating in sporting activities at school due to not being allowed to wear sport uniform for the whole day and 97% of students would be more willing to participate in sporting activities if they were allowed to wear their sport uniform.

Students our age should be getting an hour of physical activity everyday as it is of great importance for our overall health and well-being and changing the sport uniform policy will better enable students to reach this guideline.

The SRC are currently working on a proposal to present to School Council next month. We hope that after doing this we will be able to implement a two week trial where students are allowed to wear their sports uniform to school if they have any sporting activities, whether it be inter-house sport or inter school sport try-outs. Given that there is a high percentage of students that follow the policy during the trial, we hope for this to become a permanent change.

We would like to thank all the students who completed the survey and if anyone has any queries, suggestions or concerns about this issue please don’t hesitate to contact an SRC member.

For the last couple months, the SRC has also been working on making Nossal a SunSmart school after students expressed their concern for this matter via our online SRC suggestion box. Since then, we have been working on making sunscreen more accessible for students and also brainstorming methods to advocate SunSmart practices. Late last week, our first sunscreen dispenser was fitted to the wall opposite the canteen and we are currently working on advertising its use closer to spring. The SRC will be monitoring the use of the sunscreen dispenser to consider buying more to place throughout the school.

Lastly, the SRC wanted to provide some inspirations to our students, as well as create transparency from students to teachers and create an overall better school community. Through Humans of Nossal, we will soon be sharing touching and motivating stories from teachers, and soon be moving on to students and alumni. The posts will be posted on Nossal's Instagram so give it a follow and stay tuned!

And remember, as always, if you have any suggestions don't hesitate to let us know!

SRC Suggestion Box: https://goo.gl/forms/IgUFVhiUndOK9WHk2

Sports News

Somathyda Rim

On Thursday 19 July, three very talented Nossal students competed in this year’s state cross country at Bundoora Park. Nikola Mandic, Annabel Keecha-Milsom and Gurkirt Singh had all successfully represented the school in what would be known as a very prestigious competition and completed an amazing run considering the cold conditions that the day had brought. We congratulate all three students for their resilience, determination and strong school spirit which was demonstrated through their runs on the day. The results obtained by each student can be found below.

Nikola Mandic (Under 15s) ran 3km and placed 11th

Annabel Keecha-Milsom (Under 16s) ran 3km and placed 27th

Gurkirt Singh (17-20 year olds) ran 5km and placed 25th

The Story of Strine: A Look Back on our Language

Jordan van Rhyn

Winston Churchill once said that the English spoken in Australia "represents the most brutal maltreatment which has ever been inflicted upon the language that is the mother tongue of the great English nations."

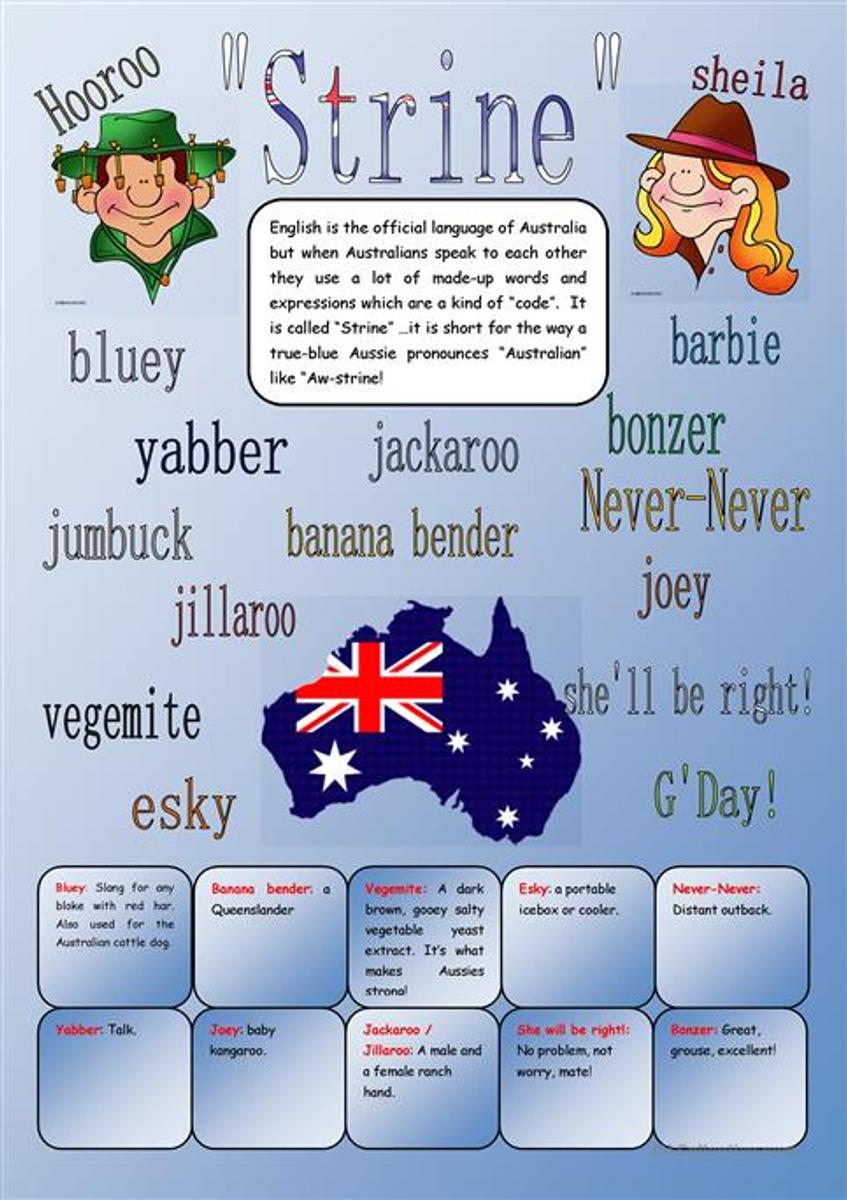

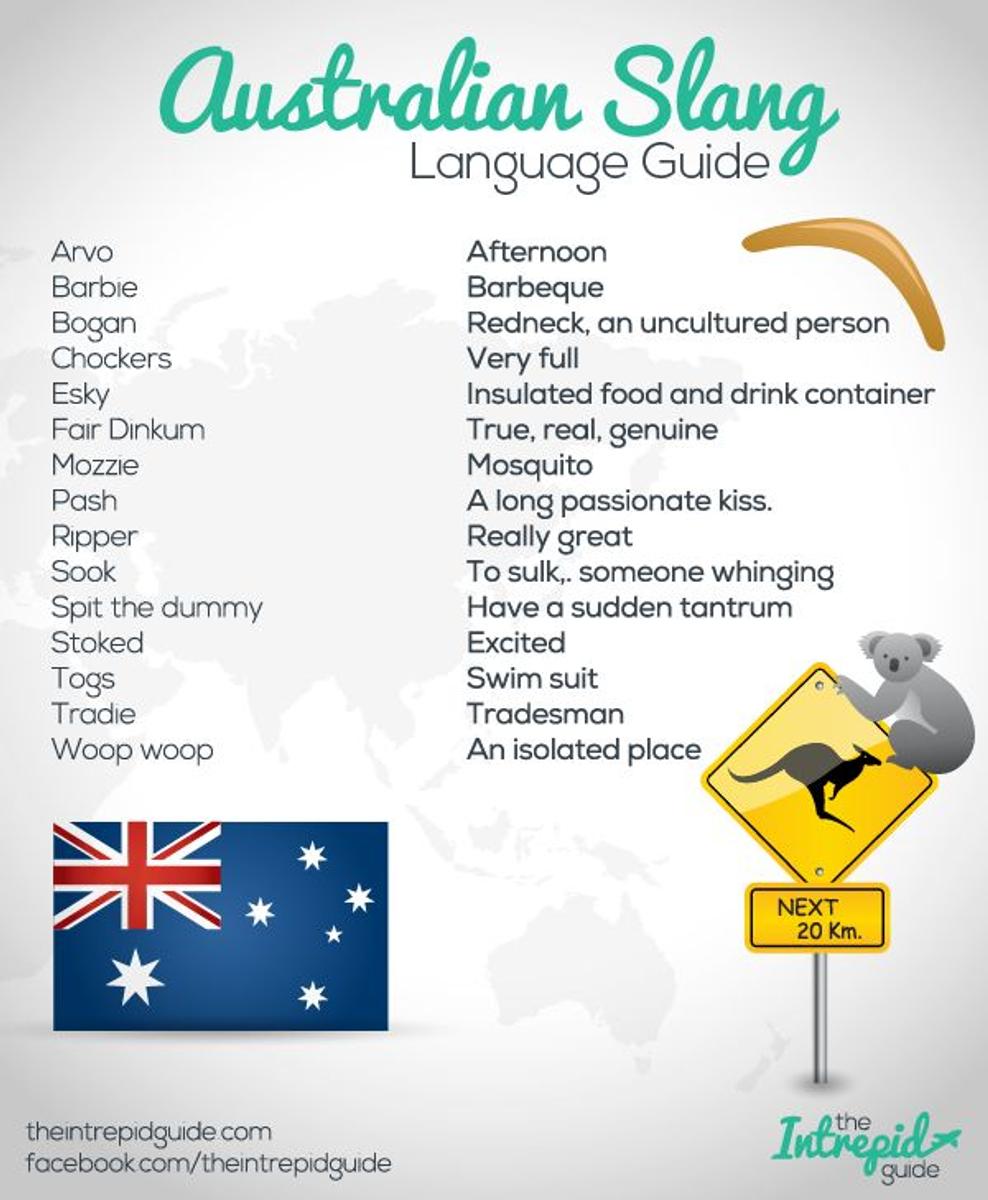

His comments were emblematic of a larger tendency towards prescriptivism, the view that some varieties of language are of more value than others. The history of Australian English – occasionally semi-facetiously referred to as 'Strine', a reference to an excessively broad pronunciation of 'Australian' – has been fraught with debate over linguistic value and, overarchingly, the country's attempt to determine what the Australian identity is – what exactly it means to be an Australian.

As the lingua franca of Australia, Australian English is spoken by roughly 20 million Aussies, including 3.5 million second-language speakers. While the popular consciousness is generally aware of the influence of British English on Australian English, the reality is more complex: Australian English is the lovechild of British English, spoken by the first European settlers of the country, and other languages, like those spoken by the Indigenous population and by migrants to Australia, particularly those who arrived in Australia's post-war population boom (1950s – 1980s).

British English is perhaps the most salient contributor to Australian English – in his book Speaking Our Language: The History of Australian English, lexicographer Bruce Moore describes the phase of 'levelling' experienced by the first colonists after the establishment of the first colony at Botany Bay in 1788. The roughly 736 convicts who survived the eight-month trip from Portsmouth came from all across the British Isles, including Scotland and Ireland. To make the process of communicating with fellow convicts easier, says Moore, the convicts would have "unconsciously changed" some elements of their speech almost immediately. And in the following decades, the first generations of children born to the convicts, having grown up together, would have established a common standard for English which would go on to become Australian English. The influence of these forms of English is prominently visible in Australia today: in colloquial British slang like the ever-present 'mate' and Cockney rhyming slang like 'Barry Crocker' (for 'shocker'). Even the Australian term 'Sheila', meaning 'woman', derives from the Irish feminine name 'Sile'.

In addition to British influence, Australian English has been modified by Indigenous Australian languages. Bruce Moore says that early Australian colonists "needed to come to terms with an alien world, ... the flora and fauna, and the landscape in which this flora and fauna existed." To make up for a lack of vocabulary, settlers would borrow from Indigenous languages around the Botany Bay settlement. In his 1798 An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, naval officer David Collins stated that "our knowledge [of Indigenous languages] consisted at this time of only a few terms for such things as, being visible, could not well be mistaken; but no one had yet attained words enough to convey an idea in connected terms." Most borrowings from Indigenous languages were from languages near to British settlements, including from the Dharuk ('wombat', 'dingo', 'koala'), Kamilaroi ('brolga', 'gilgai', 'budgerigar'), and Yuwaalaraay ('bilby', 'galah', 'gidgee') languages. Although many borrowings have now become disused, borrowings from Indigenous languages have maintained a small but prominent place in the Australian identity.

Alternatively, settlers constructed new words from existing English ones, often with a 'native' or 'bush' modifier (e.g. 'corkscrew grass', 'apostle bird', 'native dog', or 'bush tomato'). In fact, the 'bush' modifier came to be recognised as an element of early Australian identity, being applied to a genre of poetry known as a 'bush ballad'. These poems employed a straightforward structure with colloquial and idiomatic Australian English. In fact, The Bulletin, formerly Australia's longest-running publication, was a centrepoint for titans of Australian bush poetry such as Henry Lawson and Banjo Paterson.

More recently, Australian English has been influenced by the languages of post-war migrants to Australia, including Greek and Italian. During the aftermath of the Second World War, Australian Prime Minister Ben Chifley instituted the first mass-immigration programs through the newly-formed Department of Immigration. The first Minister for Immigration, Arthur Calwell, famously proclaimed that Australia must "populate or perish". As a result of these immigration programs, which aimed to increase the country's population by 1% per year through immigration largely from European nations such as the United Kingdom, Italy, and Greece, Australia's linguistic diversity increased dramatically: borrowings from Italian ('cappucino', 'al fresco', 'diva', 'finale') and Greek ('bouzouki', 'gyros', 'tzatziki') are commonplace on Australian streets.

These influences on Australian English – British settlement, Indigenous borrowing, and post-war migration – have closely mirrored Australia's history. Author and language expert Kel Richards stated that "the story of our language ... is actually the story of the nation": as Australia began to establish an identity distinct from Britain, its language grew to become more individual.

But the history of Australian English has not been without challenge. By the time Australian English came to be recognised as a separate form of English in the late 1800s, the country had developed a proto-regional identity, replete with distinct literature, a fierce sporting tradition, and the cultural values of egalitarianism and anti-authoritarianism which remain to this day. Concurrently, however, the British Empire remained the world's most powerful state, and this resulted in internal pressure to conform to British English and its associated Received Pronunciation. In response to this pressure, schoolmasters began to emphasise education in diction and elocution in the so-called 'elocution movement'. The movement continued in vogue until the First World War, when a more comprehensive national identity, formed around the crux of the ANZACs, Australian 'diggers', and national legends such as the Battle of Gallipoli, emerged. This identity was one that took pride in the distinctiveness of Australian English when contrasted against British and other Commonwealth soldiers. According to Bruce Moore, this was when Broad Australian English was established, beginning with the works of Australian poet C. J. Dennis, whose famous verse novel The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke was distributed to Australian soldiers in the thousands.

When the Second World War began, 25 years after the beginning of the First, Australia's identity as a nation based on mateship, egalitarianism, and anti-authoritarianism had been firmly established. The cementing of Australia's national identity, coupled with the decline of the British Empire after the Second World War, gave rise to the distinct regional variety of Australian English which remains largely unchanged today.

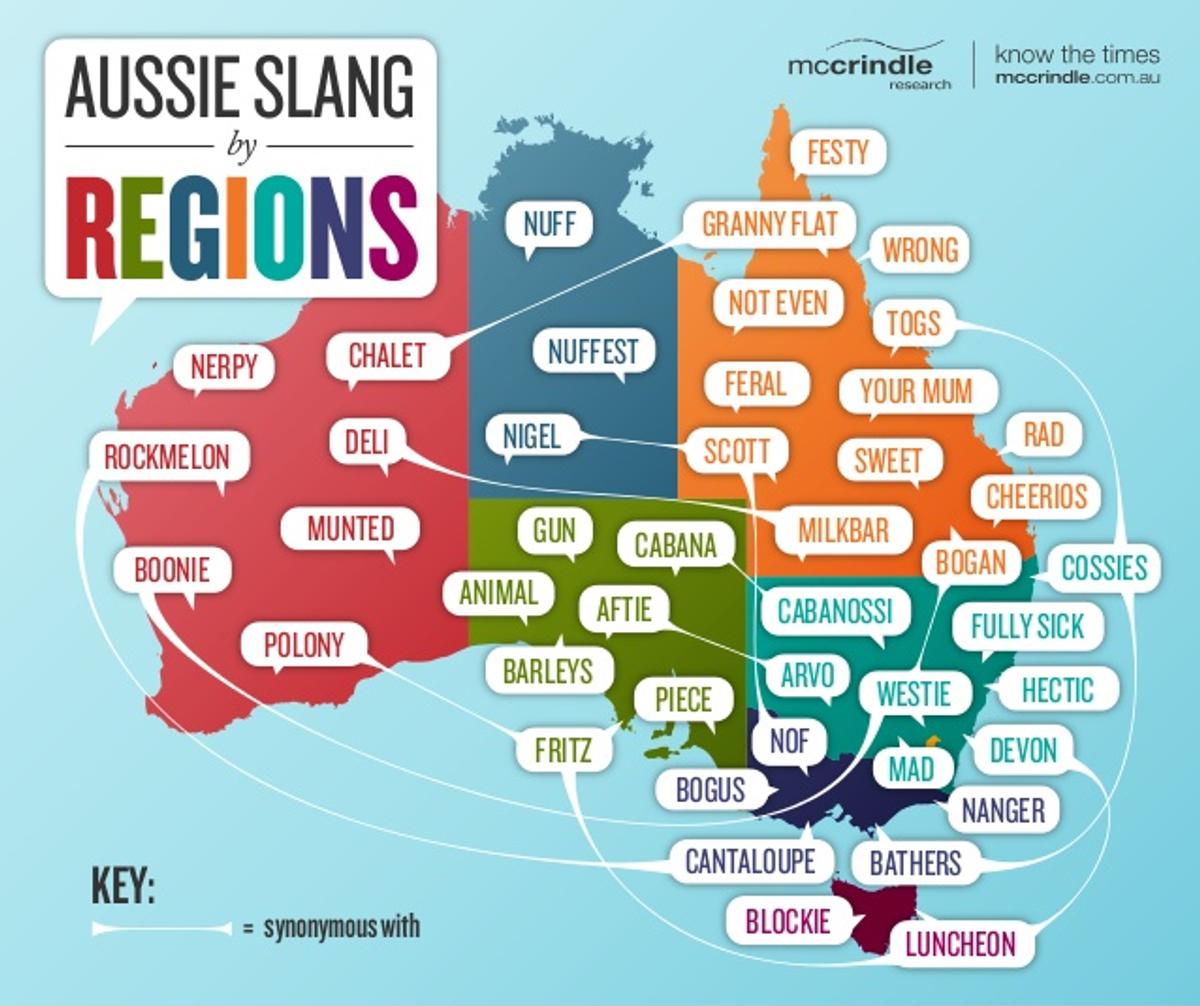

Contemporary Australian English is being influenced by cultural and technological factors. Among them are the influence of American English, as well as technological factors such as the rise of the Internet and mass media. The status of the United States as the predominant global power, and one which produces much of the television, film, and music consumed in Australia, has influenced Australian English with terms such as 'okay', 'you guys', and 'gee'. American influence has, however, met with some resistance from Australians who feel that 'Americanisation' will have negative impacts on Australian English and Australian culture. Additionally, according to linguist and University of Bangor professor David Crystal, "the internet has speeded up the process of [language change] ... so you notice [it] more quickly." Australian English has not been exempt from this increased rate of language change. As communication shifts towards taking place digitally, some, such as Don Bemrose, founder of the East Riding Dialect Society in the United Kingdom, have expressed concern that regional varieties are "dying out" and becoming homogenised. But others, such as language expert Rachael Tatman, aren't concerned: "Television and mass media can be a force for linguistic change, but they're hardly the great homogeniser that it is often claimed they are."

Ultimately, although Australian English will continue to change – as it has over the course of more than two centuries, with British, Indigenous, and migrant influence – its role in shaping Australia's national identity will not. While our language will inevitably change and shift with the moving of social tides, for now, at least, it looks like Australian English is here to stay.

The Explainer: Macedonia-Greece naming dispute

Leo Crnogorcevic

When Macedonian Prime Minister Zoran Zaev and his Greek counterpart Alexis Tsipras said last week that “we are here to heal the wounds of time”, he could not be more right.

For over two decades, the issue of the Macedonian name dispute has plagued Greek-Macedonian relations, fuelling hatred and toxic sentiments. Just how, then, can a name matter so much?

To begin, we must first understand the socio-ethnic background about this conflict. The two sides to this dispute - Greece and Macedonia - are both located within the south-eastern region of Europe known as the Balkans. For centuries, this place has been plagued by intricate ethnic conflicts, which most recently blew up in the late 1990s. The history of the region is diverse and complex, which has unfortunately led to adverse outcomes more often than not.

Much before the Ottoman invasion of the Balkans which preceded the modern-day nation-state configuration of the region, defining ethnicity was much more difficult. Central to this particular naming dispute is the identity of Alexander the Great. Going from a young king to a ruler of a vast empire stretching from the Adriatic Sea to the Indus River, he is one of the main players in this long-ranging conflict. He was initially the King of Macedon, an Ancient Greek kingdom inhabited by Greek tribes.

Fast-forwarding two and a half millennia, a little-known liberation movement against German occupation of Yugoslavia grew to become the largest resistance against Nazi rule in World War II. These ‘Partisans’, led by Marshal Josip Broz TIto, were steadfast communists. They had seen the destruction caused over the years by disputes between Balkan peoples, and emphasised ‘brotherhood and unity’ of the South Slavic people over nationalist propaganda purported by certain groups. Tito’s rise to power saw a great restructuring of the country. Yugoslavia became a federal republic, comprising six republics within it to allow each of the six main ethnic groups to have some level of autonomy. This allowed the central government to protect the individual nationalities’ recognition, whilst promoting a united, left-wing Yugoslav identity.

One of these republics was the Socialist Republic of Macedonia. The region that made up the republic was scattered between various powers over time, most notably Serbia and Bulgaria. Its inhabitants spoke a language very similar to that of the neighbouring Bulgarian, but their identity was at a crossroads. They were Slavic, for sure, but how could they differentiate themselves and find their own place within this vast region?

More and more people here started to identify as ‘Macedonian’ - a unique South Slavic ethnic group. This did not cause any problems until the collapse of Yugoslavia in 1992, where the fledgling Macedonian republic suddenly gained independence. They had to come up with an identity and national symbols - a flag, a coat of arms and a national anthem. Herein lies the problem. The pioneers of the independent Macedonia simply removed the ‘socialist’ prefix from the state’s official name for it to become the ‘Republic of Macedonia’, still commonly known as Macedonia for short. However, they also began to adopt many symbols of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon, using the Vergina Sun as the basis of their flag and even naming their main airport the ‘Alexander the Great Skopje International Airport’.

Greece naturally took offence to this. They saw it as unashamed appropriation of their historical past. With Alexander the Great being an ethnic Greek, they feared that their own northern region, itself named ‘Macedonia’, would be subject to possible territorial expansion by the (Republic of) Macedonia. These fears of course had no basis, but with nationalist governments in power in both countries, the two neighbours continued to outdo themselves over ridiculous responses to the issue. Macedonia offered bizarre theories as to how the modern-day Macedonian ethnic group had descended from Slavic and Greek intermarriage within historical Macedonia, whilst Greece took offence with the ostensibly least controversial aspect of the identity dispute - Macedonia’s name.

Taking the matter before a mere identity dispute, Greece refused to recognise the name ‘Macedonia’, as it matched that of their northern region. Greece protested and protested with considerable success, with Macedonia only admitted as a member of the United Nations under the temporary name ‘the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia’ or FYROM for short. The official name ‘Republic of Macedonia’ was seen more favourably on the Greek side, but never quite good enough.

Over the next two decades, the name continued to be a persistent problem. Diplomatic relations between the two countries declined due to the matter, hindering economic cooperation; Greece even refused to allow for the moving-forward of Macedonian attempts to join the European Union (EU) until they changed their name.

The situation seemed doomed.

That is, until now. With Tsipras’ Syriza coming to power in 2015 and Zaev’s Social Democratic Party winning the 2016 parliamentary elections, the two leftist governments were presented with a historic opportunity: to finally resolve the issue. Following years and months of talks and summits, it was revealed that Macedonia’s new name would be ‘North Macedonia’, distinguishing it sufficiently from the region of Macedonia in Greek eyes.

While the conflict seems to be much ado about nothing, the matter is both depressing and inspiring. It is sad that it has taken this long for a matter like this to be concluded. Nationalists on both sides have pursued chauvinistic ideologies which are based on ethnic superiority, rather than cooperation and common sense. The fact that it is all over, however, gives hope for a more peaceful Balkans. That, more than any promise of EU membership or economic cooperation, continues to be the greatest success.

More than anything, the conflict ultimately shows the absurdities of national identity. Whilst Macedonians were probably at fault for attempting to use Greek heritage to satisfy their own identity crisis, and the Greeks reacted harshly by not accepting the perfectly-neutral ‘Republic of Macedonia’ as a sovereign state’s name, it can all be traced back to a single concept: the concept that we are somehow all members of different communities, defined by abstract aspects of national identity - an designation which has over the years adopted far too much significance.

Editorial: In Helsinki, Trump Accelerates American Demise

Jordan van Rhyn

U.S. President Donald Trump met with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Finland’s capital of Helsinki on July 16, ostensibly to begin in earnest the two Presidents’ relationship. But it became only yet another signal of what many had already feared: that Trump’s presidency would hasten the demise of the United States as the world’s foremost power. As Trump met with Russian President Vladimir Putin, praising the latter for being “extremely strong and powerful” in his denial of Russian interference in the 2016 American presidential election, Western leaders across the globe gave tepid lamentations, not wanting to endanger their relationships with the United States. Our own Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull quipped that Trump was “a patriot … an American patriot.” Britain’s Prime Minister Theresa May refused to respond to Trump’s actions, even after he called her proposals for Brexit “very unfortunate” and publicly supported May’s rival for the Prime Ministership. On the domestic front, Republican senators have given one of their most strident admonishments of the president yet (to the tepid extent that Republicans are willing to criticise the leader of their party), but the tide of criticism seems to have passed with no lasting effects.

We ought to make no mistake: Trump’s cuddling-up to Putin, a man who routinely assassinates political allies and restricts freedom of the press, is dangerous and threatens to destabilise the decades-old rules-based international order which has brought unprecedented peace and stability to the world. Even leaving aside Trump’s business connections to Russia and its oligarchs, we should be concerned about the implications of the Helsinki summit. Putin, it seems, is aiming to return to the days of the Cold War, when Russia was one of two dominant global powers (the other being the United States). But Russia can no longer hope to be the superpower it once was - its economy is smaller than that of Italy, and less than one-tenth of that of the United States - which means that it is puzzling that the American president should spend so much resources, time, and political capital developing a better relationship with Russia, leaving aside the strong possibility that Trump is somehow under the financial or political influence of the Russian Federation. If this were the only impact of Trump’s obsession with Putin, perhaps it wouldn’t be so bad. But, as Trump spends time embroiled in the Russia-U.S. dynamic, he neglects - perhaps fatally - the nation’s previous policy of increased involvement in the Asia-Pacific, where China looks to counteract American political and economic influence. In doing so, he opens the way for China to become the regional, and eventually global, hegemon. And, as much as America has overseen and participated in grievous human rights violations in its time as global policeman, it does not seem that China will do much better.

All this, of course, to say that, to the dismay of many Western leaders, it seems that Trump is too distracted to see the long-term picture. As Trump seeks to cozy up to Putin, all he is really doing is putting a mentos in the coke bottle of the fall of the American republic.

Get in touch

Jordan

Editor-in-chief

van0004@nossalhs.vic.edu.au

Leo

Editor-in-chief

crn0002@nossalhs.vic.edu.au